.

Director/Screenwriter: Samuel Fuller

By Roderick Heath

Dramatically terse and unsubtle, even by Samuel Fuller’s standards, Verboten!, one of his least-known films, explores the panorama of Germany Year Zero and wields the usual pressure-point Fuller melodrama with a social and historical conscience-raising purpose. Verboten! straddles the gamut of Fuller’s capacities and unevenness as a director. Made on a low budget, full of weird casting choices, curtailed ideas and fragmented story arcs, it still delivers with a force and clarity of intelligence the desired impact few other directors could ever muster, as it charges into the heady atmosphere of the post-War mixture of abject defeat and lingering horror. The undercurrent of menace that pervaded so much of the Western world in trying comprehend what kind of madness had overtaken it, what it meant to a society that had spent centuries building itself to an apotheosis only to come to a shattered and shameful ruin, and whether the forces and individuals who had contributed to it might lurk still within a landscape of seeming victims, is explored in a panoramic depth through a thriller plot.

Fuller commences with an excellent extended combat sequence (which anticipates in structure that epic duck-and-hunt finale in Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket [1987]) in which Sgt. David Brent (James Best) and the remnants of his spearhead unit enter the bombed-out German town of Rothbach in pursuit of a cunning sniper. The sniper takes out Brent’s fellows and hits Brent in the leg, but the wounded man manages to corner his quarry and blow him away. Brent collapses and awakens to find he’s being sheltered and cared for by Helga Schiller (Susan Cummings), a young woman who’s determined to prove to him that “there’s a difference between a German and a Nazi.” She has been terrorized by bombing raids and her own side’s soldiers, embodied by the swagging, hypocritical SS officer (Robert Boon) who took over her house to use as an observation point. Helga lives with her invalid mother (Anna Hope) and her younger brother Franz (Harold Daye), a Hitler Youth member who lost an arm in an air raid and is understandably unhappy about it.

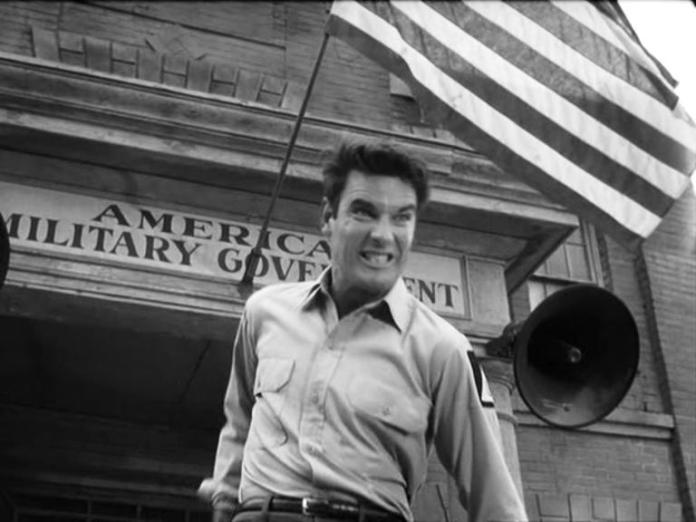

Brent and Helga manage to survive a few close grazes with the SS man’s fanatical, bullying, and half-suppressed lechery until the rest of Brent’s unit finally penetrates the town and drives out the remaining defenders. Brent spends time in hospital recovering from his wound, long enough for the war to officially end, and, when discharged, manages to land himself a civilian job in Rothbach aiding the military liaison so that he can marry Helga without fearing the army’s no-fraternisation policies. Just after Brent’s told Helga about his good fortune, a former neighbour of hers, Bruno Eckart (Tom Pittman), returns from his service weighed down by gear and completely exhausted: she has to tell him his former girlfriend is dead. Brent and Helga get married, and their lives proceed in relative calm until Helga becomes pregnant. But Bruno, Franz, and a collective of other angry, resentful veterans form an unofficial chapter of the pro-Nazi anti-occupation force known as “Werewolves” with an eye to both running the black market in the Rothbach district and to stirring up insurrection against the Americans. This puts Brent’s job in peril when he reacts to the insults of one of Otto’s followers in leading a protest march and gets into a fistfight.

Verboten! is as rough and ready as much of Fuller’s work, particularly from the latter half of the ’50s, but it also suggests a highly personal project, and not merely in how the raw material of the story and portrayal of the setting seem based in autobiography, anticipating his own The Big Red One (1980) as well as moving past the mere combat drama of several of his earlier films. The immediacy of Fuller’s interest is also apparent in its fierce eagerness to lay bare not only the wrongdoings of Nazism, but also the problems of peace, and the narrative’s attempts to reconcile given opposites: culture and barbarity, conqueror and conquered, idealist and cynic, Germanness and Americanness, victim and victimiser, male and female. One of the pleasures of Verboten! is the definite sense of detail that’s easy to perceive throughout, the small aspects that decorate the sets and performances in spite of the fairly low budget. The post-war landscape, in the microcosm of Rothbach, is one of huddled, cueing, hungry people; seamy profiteers; and survivors of the concentration and labour camps still wearing their striped uniforms. Buildings have messages from families to missing loved ones painted in big, bold letters amidst instantly dated propaganda expressions.

The titular word “verboten” has several connotations, applying both to the cross-cultural romance that is the first rule Brent breaks, leaving him dangerously vulnerable, and also to the underground survival of Nazism: painted on the wall of the rail car the Werewolves use as their HQ, and where Brent ended his own war by killing the sniper, are the words “Heil Hitler”—except that “Heil” is later painted out and “Verboten” painted beneath, the ironic concealment of the survival of Hitlerian ideals. Emblems of power and ideology are painstakingly replaced, but the true situation is far less obvious. A peculiar, recurring image, first seen looming over the spot where one of Brent’s squad mates is killed, is a silhouetted figure sporting a question mark and the words “Sieg Heil” written above. Later it appears all about town like some more sinister Nazi riposte to ubiquitous “Kilroy/Foo/Chad Was Here” graffiti craze: this is the emblem of the paranoia of the post-war period the film tries to recreate (the motif also suggestively evokes the poster for Fritz Lang’s M, 1931). One irony here is that whilst the black market and sabotage undoubtedly continued long after the war, the actual Werewolves only ever performed one combat mission and otherwise survived only as bogeymen to taunt the minds of the occupiers.

Although Brent and the American forces continue to try and peaceably govern the country, the drama at the heart of Verboten! is driven by its German characters and their efforts to contend with their poisoned, broken legacy. The liaison office is a place where the occupying bureaucrats have to deal with contentions and enmities between the Germans that resemble a civil war. One of their employees in charge of helping track down wanted Nazis, Eric Heiden (Sasha Harden), is alerted to the fact that his brother, a significant war criminal, has escaped from custody: Eric recounts to Brent the damage that his brother wrought on their family and, thus, why he’s as interested in seeing him nailed as anyone else.

Fuller’s journalistic, investigative sensibility is at play throughout Verboten!. He approaches his subject by stages, firstly immersively in following his American hero, then through a change of perspective that places his German protagonists at the forefront of the action, and then exploring the problems in rhetorical layers. Fuller repeatedly reverses perspectives, most cunningly in the single shot in which Helga bids Brent farewell after his first return visit, with Otto lumbering under a load of gear up the road behind him; Helga doesn’t notice him until Brent leaves the frame, and hurriedly ushers him into her house. There, they speak with the exhausted realism of survivors, Helga happy to admit she’ll contemplate marriage to an American because it will make survival easier, and Otto noting as they both begin to stuff their faces with Brent’s chocolate, “For the first time your sex has the advantage over mine.” This marvelously wry, matter-of-fact volte face, with its keen behavioural accuracy, has specific consequences later, when Otto tries to break up Brent and Helga’s marriage by telling him what she said at this moment. This revelation causes a violent, if temporary, split between the pair, as Brent’s sensibility, still unworldly in spite of his baptism under fire, is shocked by the notion that anything less than true love could have made Helga marry him.

But the scene’s less immediate, but more effective effect is to show up the self-satisfaction of the American conquerors, and signal the thin ice everyone’s sliding on. Otto, whose cool, slightly insolent charm conceals a fiery, utterly dedicated Nazi, initially, favourably contrasts Brent in his laidback charm (the faint whiff of the California surfer boy that comes off actor Pittman adds to this), seemingly schooled by years of warfare in how to sit still, take stock, and not waste energy. Otto’s deeply hardened, asocial expedience only emerges slowly, as he makes his pitch to his fellow veterans in an old rail car that becomes their headquarters and contends with the irritable Helmuth Strasser (Dick Kallman), who doesn’t want anything to do with Otto’s Fourth Reich hopes but is all too happy to do some serious black market profiteering and to stir up the occupiers. Young Franz becomes increasingly enthralled by Otto and entwined with the Werewolves operations. Otto’s plan proves effective in seizing shipments of food and supplies, thus both increasing his own power whilst undercutting the Americans’ attempts to prove the generous conquerors.

Fuller’s distinctive sense of form not only builds a narrative, but also creates portraitist vignettes, like those of Strasser’s initial rave to Otto and Eric’s talk with Brent, or a GI displaying a young woman who’s had her head shaved by her angry brother to the CO of the liaison, that serve their own rhetorical function, expanding the film’s social and moral landscape as inextricable from the individual protagonists, and avoiding wrapping everything up in neat bundles. Fuller attempts to encompass a whole epoch, both in immediate and philosophical terms, and in the broadest style, as he would later do closer to home with Shock Corridor (1963). Particularly acute is the way the drama keeps revolving around the same locales, particularly the town’s main public areas—Martin Luther Platz and Adolf Hitler Platz—entwining historical and contemporary Germany and their divergent values. The opening battle of Brent and his buddies and the sniper, and then the less recognisable war between the occupiers and the Werewolves play out through social posturing, until Brent amusingly loses his temper with the protestors after declaring, “We’re not here as liberators! We’re here as conquerors, and don’t you forget it!” and then tries to backpedal to put across the Marshall Plan ideals.

Otto’s efforts begin to unravel when he goes too far in stealing medicine intended for hospitals, something Strasser protests: Otto has the other Werewolves beat Strasser senseless and then executed with a knife to the heart. Franz, whilst still hero-worshipping Otto, is disturbed enough by both the theft and the murder that he talks about it in his sleep, alerting Helga to his involvement. Helga forces Franz to accompany her to the war crimes trials just starting up in Nuremberg, and Franz sees the filmed evidence of Nazi horrors, finally comprehending the obscene truth and turning him vehemently against Otto. Fuller’s employment of real concentration camp footage and his portrayal of the Nuremberg trials is more like an educational reel than a realistic recreation, but his attempts here are a great distance from the preachy genocide tourism of Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), and his desire to elicit passionate engagement in both Franz and the audience is linked and urgent: Helga grips Franz’s chin to stop him looking away. Franz is inspired enough to blow the lid off Otto’s operation. He tries to steal his list of confederates, leading to a final destructive fight between the two in the rail car that starts a conflagration that consumes the last of the Nazi cause.

Like many of Fuller’s films, Verboten! makes use of shorthand caricatures, like the sleazy SS man, the why-can’t-we-get-along town Burgemeister, and a cigar-chomping American officer, that are a bit cheesy, even if they do aid Fuller in establishing his texture and oppositions with crystal clarity. Verboten! isn’t as deliciously bizarre or full-bore powerful as Fuller’s best works, the production limitations do hamstring it, and the acting is uneven—neither Cummings nor Daye are convincing Germans. The quickie running time can’t contain everything Fuller tries to do, and the finish is unfairly abrupt, though in one sense, this abruptness is a fitting consummation of Fuller’s realism: one story may finish, but the true situation will take years to resolve. And then there’s the embarrassingly crappy Paul Anka theme song (“Our love is verboten!”—yes, it’s as bad as it sounds).

Nonetheless, Verboten! is a rip-roaring little film, and one that looks remarkably good thanks to Fuller’s vivid eye and the technically excellent work of DP Joseph Biroc. His carefully lit, heavily shadowed, deep-focus visuals seem to keep the energy and beauty of noir film alive long after most such intricacy had vanished from Hollywood cinema. Fuller’s stylistic creativity here seems, indeed, to have had an impact on other filmmakers, especially in his use of classical music throughout, still an uncommon practice at the time. The concussive strains of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, anticipating its similar usage in The Longest Day (1962) in establishing the apocalyptic struggle, give way to swooning quotes from Liszt and, most impressively, an electrifying montage of the Werewolves’ crimes and the occupiers’ hunt set to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” 20 years before Apocalypse Now. Here Fuller’s ironic counterpoint of high culture and down-and-dirty business is at its most vital and synergistic.

Excellent review – this film seemed to have been buried by a certain kind of embarrassment, I think, plus it was too late for the the immediacy of the Trümmerfilmen, and well after the WWII film revivals were popular. The message wasn’t clear enough for a lot of film-goers, too, they had to use their heads, and they mostly wanted escapism at the drive-ins.

It still had that flavor of “bad Nazis, but not us” apologia to it, but it does attempt to show the basic goodness of the average person, rather than the turn-the-other-cheek of many from that period, which was about the right timing for that. This would’ve been better if it was a bit longer and more coherent, or shorter and more focused, like “Die Mörder sind unter uns”, which I think was the least apologist of the Trümmerfilmen.

I had a friend whose father was in the black market in post-war Germany, with stories of suitcases full of counterfeit dollars used to buy a train-car load of “salted” cigarettes – only the top layer was real, the rest old newspapers – or walking thru Berlin with a quarter mil in diamonds in a camera case, and he believed the worst of the sabotage and such was much more a turf war between the cold war sides using German proxies, and he likened it to Al Capone.

Fuller did more with less than so many other directors, he was a genius in that respect – “Park Row” is a fun watch, a tempest in little more than a teapot’s footprint, and like this one, made with a lotta no-names.

LikeLike

Van the Man:

Yes, there is a bit of that apologia, but it’s so cleverly mitigated in that scene between Otto and Helga where Helga’s desperate need to prove to Brent that not all Germans are Nazis gives way to a measured, innately cynical tone that demonstrates survival dictates many things and ideals are luxuries. It’s a film then that manages to present some genuine moral ambiguity in a fashion that’s hyped up but not dumbed down. Verboten!’s definitely a work from the tail end of the ‘50s war genre films, coming just before that genre was insistently super-sized into white elephant prestige flicks. You compare it to some German films like The Murderers Are Among Us, and that’s fair enough, but I tend to think more about the other English language productions on the theme and what they hadn’t done – I couldn’t help but notice that this avoided some of the tricks of earlier Hollywood films dealing with similar material, like The Devil Makes Three, where the themes of romance and lingering Nazism were safely severed from reference to the Holocaust, or the basic tear-jerking of The Search. It certainly would have been better if a bit longer, just a little less Fuller-to-the-point, but I actually liked how the film refuses to wrap up everything neatly and develop every aspect to the fore – it’s all part of the landscape, and Fuller did that sort of thing fiercely well. Still, it doesn’t quite build up that same dizzying intensity as the likes of The Crimson Kimono, its immediate successor in Fuller’s studies in post-war ethnic relations melded with thriller plot, where all the elements and commentary are keenly integrated into the main thrust of the story.

That’s a great anecdote, BTW. It’s certain the paranoia amongst the occupation forces was as high as the illegal activity was widespread.

I understand that Park Row was actually Fuller’s favourite of his films, but I’ve been unable to track it down.

LikeLike

This one is not well known, I`ve seen only small parts of it and knew Fuller because of his work with Wenders (by now I know more ,its on YT). I have no idea if anyone was a convincing german but the spelling seems to be right. The werewolf plot: Very unlikely,there were no such activities in most of Germany (but some in later Czechoslovakia and one in Aachen). The Trümmerfilme: I didnt know they were known outside Germany. 1959 was also the year of Wickis “Die Brücke” which I like to recommend. Another anecdote: a woman told me that at the end of war they had a lack of everything, so she took a huge Reichskriegsflagge (red white black stripes) and made a dress out of it. Then she and her husband went dancing.

LikeLike

Hi maren:

Dancing in a Reichskriegeflagge? That really sounds like something out of a Fuller film!

I haven’t seen Die Brücke although it’s one of those films perennially on my want-to-see list. I’ve seen some very good West German films from the ’50s detailing the war-time mood, though, including Robert Siodmak’s The Devil Strikes at Midnight and Helmut Käutner’s The Devil’s General – films that ought to be better known.

LikeLike

One aspect to many of the immediate post-war films set n Germany is the rather “cleaned up” aspect to the buildings and especially the clothing – even Trümmerfilme had that aspect to a degree, altho none ever got to the level of rags that many were wearing just to stay alive – many people would sell every stitch they owned just to eat; except the winter coats, especially furs – that was a life or death decision, and that edge is missing in a lot of these films.

I remember in “Battleground”, Van Johnson’e character watches two children rooting through the garbage, and looks away, saying he doesn’t even see that stuff anymore. John Hodiak’s GI says he sees it, and doesn’t want to forget it. One has a casual lack of humanity, the other is fully chrged – I think both of those kinds of attitudes make a good conflict film, and this film had both of those aspects, and some characters even aquired one or the other during the course of the film.

I think I saw my first Trümmerfilm in the late 1970s, well past any connection to reality then, but still fascinating – I don’t know how well they’re classified, I don’t mean just blown up bouildings, but I keep seeing that alluded to by many, a knee-jerk attitude, I think.

I love the red dress dancing visual – must’ve been very creative. I know my French in-laws had silk clothing right after the war made from parachutes.

LikeLike