.

Director/Screenwriter: Sofia Coppola

By Roderick Heath

The often negative, wrong-headed response to Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006) was perhaps inevitably going to inspire an aesthetic retreat on her part. Somewhere’s unexpected win of the Golden Lion at the 2010 Venice Film Festival (putting aside the dubious aspersions cast on Coppola’s former boyfriend and festival jury head Quentin Tarantino’s motives) seemed to indicate otherwise. Her name stokes furious charges of nepotism as the reason for her career successes, and yet I can’t help but think that if she were anyone else, she’d be far more acclaimed. Somewhere does bear the weight of some heavy expectations, especially from me: her poetic-realist vision is one of my favourites on the current American scene. Few working directors have managed a triple-header like she had with The Virgin Suicides (1999), Lost in Translation (2003), and Marie Antoinette, all as amusing and original as any of her ballyhooed young American rivals, wider in scope, and deeper in empathy for her characters than most.

But Somewhere . . . what to say about Somewhere? It’s a film I had a split response to in thinking initially that it was Coppola’s least original and interesting film to date, and yet with qualities that through their sheer elusiveness, refused to leave my thoughts alone. Unlike her father’s symphonic sensibility, Sofia Coppola tries to make films that soak into the soul like rain into limestone. And as much as I love the great conductors of cinema history, I also really love that breed who makes films a little like ambient music. But Somewhere resembles at the outset what I expected and feared in many ways: the sequel to Lost in Translation no one asked for.

The story, in abstraction, is more obviously sentimental and potentially commercial than her previous works: a man whose life is on the wane connects with his daughter and rediscovers his love of life. And yet from the start, the approach is firmly off-kilter. Somewhere commences with several defiantly long-take scenes, almost counter-intuitive retorts to those who complained about the repetitiousness that was part of the point of Marie Antoinette. The first is a vision of a sports car being driven at great speed around and around in circles on a desert track—a comically reductive vision of super-technology devoid of interpreting humanity. The car belongs to Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff), a movie star of the first rank who’s living in an LA hotel populated by other rich and famous individuals. His encounter with a distracted, exhausted-seeming Benicio Del Toro in the elevator is a marvelous throwaway bit, especially considering that Del Toro mumbles something about how he met Bono in the room Johnny’s staying in, which says a lot about the currency and class distinctions, as well as still-burning hero worship, that riddle the celebrity firmament.

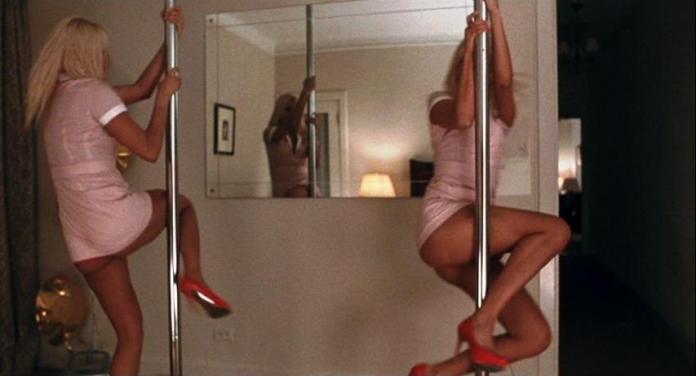

Johnny lounges about his hotel room, often going to sleep after watching performances by twin pole dancers Bambi and Cindy (Kristina and Karissa Shannon); he’s only sleeping with one of the twins, though he’s had it on with what seems to be half the women in the western world. He’s just made a meat and spuds action flick, Deadly Agenda and is doing press for it. After getting dressed down by his costar (Michelle Monaghan), who seems to have expected something after their tryst that he’s completely oblivious to, he has to field bizarrely pretentious questions from an international coterie of journalists. One journalist asks, “Who is Johnny Marco?” and this proves to be an unexpectedly loaded question.

Through paying close attention, we learn many things about him. He’s got regular lovers, and has many of the most casual kind of encounters, and yet his living an adolescent dream of unfettered promiscuity presents its own problems, as he receives a series of taunting, outraged text messages from an anonymous woman or women. He’s an actor, but, as he admits to a young wannabe at a party that inexplicably invades his room, he’s not one with any serious training or sense of his craft. He is more proud of his physical prowess, sporting a plaster cast around his left arm from an injury he got falling down some stairs but says he received on set, and a Stuntmen’s Association shirt, as badges of authenticity. His brother Sammy (Chris Pontius) recalls the days when they were young lads out for adventure. His mother’s written some kind of tell-all book about him.

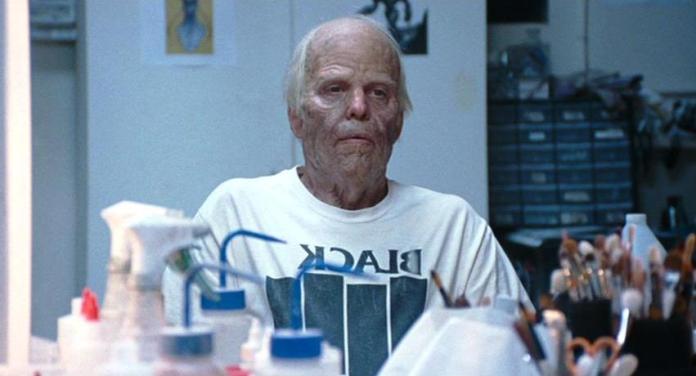

The basic gag of Somewhere is that Johnny Marco is actually a very ordinary man by many standards—a divorced scrub sliding into middle age, yet retaining his casually boyish habits like one of his increasingly seamy but blissfully comfortable flannel shirts. He’s tracing the outer edges of substance abuse while sitting around the hotel room eddying in sullen isolation. When he walks headlong into events that invoke the outside world’s perception of him as the great movie star, we feel his disorientation, as if he’s connected to a great leash that keeps him from wandering too far. It’s clear that Johnny’s stumbling through life without any essential, animating purpose. When he visits a make-up effects team for a production, they bury him in latex and then remake him as an ancient, wizened man, as if magically speeding up the process that’s already afflicting him, sealed off from the world and bound for a lonely old age. But the ghost of old responsibilities keep knocking on the door, literally embodied by his daughter Cleo (Elle Fanning), whose mother Layla (Lala Sloatman) drops her off once a week to spend some time with him, and then, abruptly, phones him during one such visitation to tell him that she’s on a trip of unknown duration and wants him to take care of Cleo for the few intervening weeks before dropping her at summer camp.

The repetitions from Lost in Translation are self-evident: the older male movie star forming a parental bond with a younger woman, the highlighted absurdities of international celebrity, the clash between enthusiasm and alienation. And yet the long takes and the generally quieter atmosphere indicate a desire to look harder and deeper. Bill Murray’s Bob Harris didn’t have anything wrong with him a few days in good company couldn’t fix, and Johnny is closer in many ways to Scarlett Johansson’s Charlotte, quietly distraught in not knowing which way to turn. This last point doesn’t, interestingly, crystallise until after Johnny says farewell to Cleo on her way to camp, and the throughline isn’t so simple as it appears. Johnny, in fact, becomes aware of just exactly how big a screw-up he’s been and just how deep his depression is by being with Cleo, and isn’t neatly rescued from from his pain. Coppola’s delight in finding both the absurdity and the humanity in things that are usually painted in bright, glossy, superhuman terms is consistently present, particularly in Johnny and Cleo’s sojourn to Italy. They go there so that Johnny can attend the premiere of one of his films and an awards show, and Coppola shows his discomfiture at being sprung upon by raving interviewers and stranded on stage with an award in his hand and a kamikaze troupe of sexy dancers performing behind him.

Coppola often reminds me here of just how much power the well-placed frame can offer, for when the dancing twins hang upside down with their pert bottoms in the air, all trace of eroticism gives way to a near-surreal hilarity. Sofia’s playful interest in the standard tropes of raunch culture, expressed in such vehicles as her video for The White Stripes’ “I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself” with its pole-dancing Kate Moss, manifests in disassembling them and remaking them with a still sensual but interestingly desexualised wonder. Unlike the simpler bit when Bob Harris found himself stuck before a stripper, these scenes work on more levels: the unblinking camera presents the twins as decadent indulgence and clumsy tease, but then alchemising into a kind of visual lullaby for Johnny, a natural end to a life full of instant gratification in turning female flesh into a kind of lava lamp, which eventually then gains an entirely different kind of sensual admiration. These scenes are bookended by a different kind of female dance, as Johnny becomes increasingly distracted and then hypnotised by the sight of Cleo practising an ice-skating routine, becoming effervescently aware of this protean, preternaturally graceful changeling he’s sired. Evidently brought up to be a model of self-reliance, with its good and not-so-good intimations about life with Layla, Cleo is articulate, intelligent, well organised, and a damn good cook.

Lots of filmmakers these days specialise in describing discomfort and creepiness in stilted conversations and awkward romancing, but Coppola is capable of describing secret insecurities and tensions giving way to blossoming affection and accord in a long scene of a couple of people playing Guitar Hero without bossing one’s attention. Somewhere is, then, consistent as her attempt to animate an almost intangible feeling, one part melancholy, one part wonderment, at the strange texture of a modern world where so many indulgences are easily available and yet human connection is a fragile commodity. If the method of doing so in Somewhere dances perilously close to cute, as father and daughter share such beatifically inconsequential moments as playing underwater and being lulled to sleep by an old waiter who sings and plays “Teddy Bear” for them with delightful incompetence, at least it’s refreshingly unguarded by the exceedingly cynical standards of contemporary Hollywood. More to the point, Somewhere is loaned its peculiar and memorable texture by an undercurrent of disquiet and strangeness. Johnny’s encounter with a blonde in a sports car (Angela Lindvall) he chases after to the gates of some recessed mansion is a cryptic piece of apparent flirtation and seems like the first act of some Sunset Blvd.-esque segue, and yet it’s just another moment in the life of a man everyone seems to know, and yet who knows very few himself.

There’s already been media speculation about who Johnny is based on, with Sofia’s cousin Nicolas Cage and her father as frontrunners, and his predicament certainly seems to have a speculatively biographical flavour. But he resembles many a male movie star who’s found himself high and dry once becoming ensconced in Hollywood’s high pantheon: such problems are why Sterling Hayden, Humphrey Bogart, and their like used to get the hell out of there on their yachts. But perhaps the movie star Johnny’s situation reminds me of most is Winona Ryder, who notoriously was prosecuted for shoplifting when the illusory state she was lulled into by the blithe world of the free-riding celebrity ran afoul of people who seemed suddenly to expect something from her. Similarly, Johnny’s being readily tossed apparently zipless fucks proves to have had a nagging, unexpected, almost existentially ambiguous price. And in yet another way, Johnny’s merely an Everyman stuck in a consumerist paradise without a sense of its borders. The landscape of Las Vegas pictured behind Johnny and Cleo, with its bizarre reproductions of the Empire State Building and fake castles, brought Jia Ke Zhang’s The World (2004) immediately to mind, a not dissimilar study of humanity clinging with increasing difficulty in a facsimile of a real world. There are significant differences, too—Jia’s characters are people trying to earn themselves a foothold in a corrosively uncaring market economy, whereas Johnny’s problem is the practical opposite: he’s won one of the modern world’s most widely contested crowns, and yet finds it gives him very little. He can indulge his caprices at whim, but he does so with a curiously self-defeating effect.

Somewhere’s gentle, eliding method is neither as insubstantial as it can seem at first quick glance, nor as profound. But it is, to my mind, Sofia’s most emotionally telling film so far. There’s a casual immediacy of feeling to moments, like when Cleo glares at Johnny when she’s met at the breakfast table in their Milan hotel room by a girlfriend who came in during the night, utterly bemused by her presence as a violation of their companionship, and the rhythmic build to Cleo’s eventual weeping fit over being abandoned by her mother and anxiety about whether she can rely on her equally uncertain father, is well-earned. The final stages of Johnny’s flight from his life comes after a phone call to communicate his grave distress to Layla gets the most mealy-mouthed of responses: “Why don’t you try volunteering?” Coppola then builds to the sort of moment where Sam Shepherd often starts his stories (I thought of, sequentially, Paris, Texas, Don’t Come Knocking, and Zabriskie Point), with his protagonist poised on the edge of nothingness and transcendence. Perhaps it’s also Sofia’s answer to her dad’s The Rain People (1969), as an exploration of someone for whom life is a drift between stations, searching for a perhaps irretrievable sense of self. Either way, whilst the movie year’s offered plenty of louder movies, Somewhere is its own modest success, and whilst that is a bit of a backhanded compliment considering that it’s the work that takes flight from thematic (if not aesthetic) risk, it’s still a genuine one.

Looking at these and all the other screencaps you sent reminds me what a gorgeous, skillfully made film Somewhere is. Coppola is still early in her career, but the positive effects of being a Coppola show – she learned well how to shoot at her father’s knee. She tells what she knows, which doesn’t make this an inherently weak film. Even though Johnny can hire private helicopters and get any girl he wants, you make the point well that he’s a regular guy in a great many ways – indeed his action hero niche rather compels him to be. I thought Fanning was superb in this film – really, everyone was. In many ways, it’s easier to sympathize with the plight of this seemingly privileged man than such films often shoot for. Look at Joaquin Phoenix’s self-loathing performance in I’m Still Here as an example of the Hollywood monster eating itself to little effect.

LikeLike

Fanning’s fabulous, and I predict great things for her. But of course my predictions are nearly invariably wrong. It’s peculiar what a totally different screen persona she has from her sister.

I often feel a little wry about potshots at privileged characters because often it’s merely members of the middle class taking out their feelings on the upper middle class. It’s interesting to me that Sofia, while she’s portrayed rich people in her last three films, communicates both the aridness that can accumulate around such exceptionalism, but also admits it can be a lot of fun, too – and that, apparently, is quite a dangerous thing to do. In any event, Johnny’s predicament reminded me a bit of Diana in Darling: in some ways his ordinariness within an extraordinary milieu seems to be a great part of his problems. I felt he’s one of those guys who needs to be working to feel in gear, and hasn’t got a compass when he’s not engaging his reactive instincts in such a fashion. The clues about his delight in physical action really made that real for me.

I do recall noting in my review of CQ that both Sofia and Roman really seem to have thankfully paid attention to his style of framing, and yes, you’re right, Somewhere bears it out: the shots are always both functional yet aesthetically well-balanced. I look forward to her tackling meatier material again though.

Gosh darn you, if you keep talking about I’m Still Here you’re going to make me want to watch it. But indeed, if anyone knows about that monster, it’s JP, after his own rehab spell and his brother’s final consumption by it.

LikeLike

Yes, that point about this world being fun is often missed or glossed over. I would totally react with the excitement Cleo had on entering that Italian hotel, but it’s more socially acceptable to think that the rich aren’t happy. In fact, they have more potential to be happy, and often are. The film shows that and that money alone is no guarantee of happiness.

I think your instincts about Johnny are right. He does seem like someone who might have been totally happy working with his hands or doing stunts on set. He’s instinctual. It’s clear he treats his fame like a rock star, indulging in all the manly pursuits, and maintains that boyish enthusiasm for the fable of that lifestyle.

As for I’m Still Here, I’m planning to write it up in a strange tandem piece. I admit fast-forwarding through parts of it, and it’s an unpleasant film in the extreme. There’s a message in there somewhere that’s worth talking about, but it seems Phoenix is more interested in exorcising his demons in a completely incoherent way than show the authenticity he says he’s striving for. You could skip it and not miss much.

LikeLike

I think the boyish enthusiasm was fast running out of charm for him, though, and that was another aspect of his malaise. He was hitting his mid to late ’30s and beginning to think about what he might find worthwhile in a future life. He was, in short, growing up. The bit with the helicopter was quite funny because it was such an obvious, “Wouldn’t it be great if you could do that?” moment, and there was the feeling that this was as much of a thrill for Johnny to do that in spite of everything as it would be for anyone.

I know what you mean about fast-forwardable movies that can still be interesting. I’m working my way through Greenberg in a similar fashion.

LikeLike

Agreed. He’s kind of going to seed. That unkempt tossle of hair doesn’t look as cute on a man moving into middle age. And yes, the helicopter was one of those great “ain’t it cool” scenes. Coppola has a great nose for the details that will get the effect she wants.

Still not into Greenberg, which coincidentally, Ben Stiller pitches to Phoenix in I’m Still Here only to be completely insulted by Phoenix.

LikeLike

I haven’t seen SOMEWHERE yet, but I have thought Coppola’s films have gotten progressively better, with the result that I actually think MARIE ANTOINETTE is her best film (and going in, I was pretty sure I was going to hate it). So, even though I’m deeply prejudiced against Stephen Dorff, you, Rod, have me looking forward to this one.

LikeLike

I, too, think Marie Antoinette is her best film, as it is indeed on my Yardsticks and Best of the 00s lists, although the plotless evanescence of Lost in Translation still works a strong spell for me: it feels just like a certain phase in my life. I’ve never liked Dorff much either, but he’s very cunningly cast and quite effectively low-key here, perhaps in a fashion that’s more worthy of my talking up than I did in the piece.

LikeLike

I am no fan at all of LOST IN TRANSLATION, though I felt so insecure about my opinion that I saw it at a local arthouse multiplex on four different occasions with friends, all of whom (save for one) vowed to sign my daeth warrant. I found it static and tedious, yet proponents always attempt to turn the tables on me by saying it’s “deliberately” that way. I liked MARIE ANTOINETTE more, but again that one is problematic for me. I guess we would have to go back to Coppola’s maiden effort, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES to find the sole instance where I liked one of her films, and that’s more of a statement there on the screenplay, than the direction. I’ve yet to discover the validity of the adoration, but I will keep on trying, and certainly this superly-written and appreciative review of a film , one in which you assert is the director’s “most emotionally telling” so far, is potentially to my taste.

LikeLike

Well, Sam….how about this weather we’re having?

LikeLike

LOL Rod!!!!!!!!

Good one!!!!

and I must say…brrrrrrrrr in the northeast!!!!

LikeLike

You see? Even our weather’s completely different. It’s like we’re from two different hemispheres or something!

LikeLike

Ha!

Way to rub it in that you are enjoying the summer now!

It was about 26 degrees last night in the city.

LikeLike