.

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

By Roderick Heath

Bram Stoker’s most famous creation has retained his culturally iconic status largely because of the many fascinatingly varied cinematic takes on the sanguinary Count. His story invites inventive interpretation, with underpinnings that are intrinsically mythic and psychologically primal, yet parsed by modern processes of rational investigation and juxtaposed realism. It’s also expressively bound up with the transformations just beginning to afflict Western society when Stoker published the work. These different tensions within the tale need only be tweaked slightly in any direction to change it comprehensively. Look at the films, and the artistic and cultural traditions therein, evolved from this work. F. W. Murnau offered a Germanic, Death-and-the-Maiden take in his expressionistic Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens (1921). Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) conjured a high-gothic, dreamlike world that belittled the neurotic repression of its heroes and offered the suavest of vampire overlords. Terence Fisher’s rip-roaring, ironically realistic Dracula (1958) stripped things down to basics and portrayed invasive sexuality afflicting the uptight bourgeoisie. Werner Herzog’s epic recasting of Murnau’s template with Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (1979), delved even deeper to create a medieval-flavoured folk myth. Various interesting TV takes in the 1970s tried to stick close to the novel and draw out its literary intricacy, whilst John Badham’s 1979 version offered Frank Langella as a romance-novel antihero. Guy Maddin’s Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002) was a blend of dance and illustrative fantasia.

All of these versions have fans and several have a claim to greatness. Francis Ford Coppola took his chances in the early ’90s, and it paid off for him, at least in the short-term. Bram Stoker’s Dracula was his last popular hit to date, and it’s still held in fond regard by a lot of younger movie fans, largely because of the magical nexus of Gen-X icon Winona Ryder and a swooning version of the tale perfect for the burgeoning teen Goth subculture. Coppola had begun his directorial career with horror films, including his uncredited work on The Terror and his mainstream debut, Dementia 13 (1963), under the aegis of Roger Corman, so he knew his way around the genre. Being a young horror fan and movie buff at the time, the promise of Coppola making a Dracula film was exciting to the deepest parts of my anatomy. And yet the result was a disappointment so severe that I’ve never quite shaken it off in estimating my opinion of Coppola. I’ve only returned to it again a couple of times in the nearly two decades that have passed since its release. I generally feel Coppola’s post-Apocalypse Now (1979) work is badly underappreciated, particularly One from the Heart (1981), Rumblefish (1983), The Cotton Club (1984), and The Godfather Part III (1990). And yet Bram Stoker’s Dracula is definite proof of many of the worst things said about Coppola in those waning days: that he was only interested in style, and that his care with the human element was gone.

The initial selling point of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (hence the title) is the nominal notion that it’s a more accurate adaptation of Stoker than usual. It does restore many elements from the novel, from some of Stoker’s surprisingly potent horror, like Dracula’s feeding a child to his coterie of vampire femmes, to supporting characters like the gallant American Quincey Morris. And yet the possessive title starts to seem more than a bit laughable, because Coppola’s and screenwriter James V. Hart’s own digressions, though different from Murnau’s, are just as great. Conceptually, Coppola’s version is epic, and that is this film’s most resilient quality. Other versions reduce Dracula to a kind of rogue seducer and rodent-like survivor, but Coppola aims to flesh out Stoker’s hinted, if never quite fulfilled, portrait of Dracula as a titan with control over men and elements, a fallen king who only needs a foothold to commence an unparalleled reign of terror. Like other more recent versions, Bram Stoker’s Dracula conflates the historical inspiration for Stoker’s story by commencing with a stylised flashback to Vlad III “The Impaler” (Gary Oldman) fighting for the survival of Christianity against the Turks.

Vlad wins, only for his beloved wife Elisabeta (Winona Ryder) to commit suicide after a false message declaring his death is shot by arrow into the castle by his enemies. Returning home to her body, Vlad is enraged when the officiating priest (Anthony Hopkins) won’t give the sacrament of extreme unction to a suicide, and he declares a vow against God, stabbing the crucifix in his castle’s abbey and drinking the blood that pours forth from it. Four centuries later, young lawyer Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves) is commissioned by his boss to replace his predecessor, the now mad and incarcerated Renfield (Tom Waits), to travel to Transylvania and arrange for the decrepit, bizarre Count Dracula to move to London. Of course, after sealing the deal with the Count, Harker is left stranded in Dracula’s castle at the mercy of his vampire brides. Dracula hits the shores of England and quickly sets sights on Harker’s young fiancée Wilhelmina “Mina” Murray (Ryder again) and her saucier friend Lucy Westenra (Sadie Frost). Lucy’s triumvirate of suitors, Dr. Jack Seward (Richard E. Grant), Arthur Holmwood (Cary Elwes), and Morris (Bill Campbell), dismayed at Lucy’s afflicted state, call in Seward’s mentor on obscure illnesses and arcane things, Professor Abraham Van Helsing (Hopkins again) to advise. He quickly diagnoses vampirism. The cure? More stake in her diet.

Whilst what follows traces the outlines of Stoker’s tale, Coppola’s wild cinematic flourishes quickly swing far away from the oneiric, creeping menace of the novel. So, too, does Hart’s addition of a new element—Mina is not just another target for Dracula’s attentions, but the reincarnation of Elisabeta, for whom Dracula hungers like the world’s oldest lovesick teenager. This notion essentially cuts against the grain of Stoker’s story, which is about rapacious, eruptive sexuality, and the way it subordinates conscious social constructs, not transcendent amorous attachment. Meanwhile, Coppola attempted to prove on multiple levels how hip he was, stirring the pot with relentless visual artifice, film references, MTV crowd casting, and subtext-ransacking figurations. Coppola set out not merely to make an effective horror movie, but to make every horror movie. His film contains direct visual quotes from Nosferatu, both Browning’s and Fisher’s Dracula, as well as The Cat and the Canary (1927), Faust (1926), Vampyr (1931), White Zombie (1932), The Wolf Man (1941), La Belle et la Bête (1946), Wolfen (1981), The Exorcist (1973), and The Shining (1980). The new central story motif comes from Karl Freund’s The Mummy (1932). The kinkier elements take clear licence from the ’70s semi-underground horror of Jean Rollin and Jésus Franco, and the deliberately po-faced mixture of mockery and erotic exploration in early scenes between Mina and Lucy resemble Ken Russell’s similarly artificial, anarchic take on Stoker, The Lair of the White Worm (1987).

But Russell’s film, less refined and expensive, is nonetheless rather better, largely because it was a pure product of Russell’s unique sensibility, whereas Coppola here is mixing and matching like a half-interested DJ. There are signs he felt an essential empathy for Dracula as a tragic villain not so far from Michael Corleone and Colonel Kurtz, but the way this is handled saps the story’s intensity and excitement. White Worm also had a strongly focused lead performance by Amanda Donohoe as a Tory bitch-goddess, whereas here Oldman as Dracula seems completely at a loss in presenting a singular characterisation when the story and style seem set on sabotaging him. The seriously fragmented impression he leaves is exacerbated by Coppola’s giddy presentations of his various guises. Dracula is, successively, a flowing-locked cavalier, a withered, ludicrously attired old drag queen, an Oscar Wilde-ish dandy, and various forms of monster. Coppola embellishes on the way Dracula ages in reverse in the novel, but he neglects to give connections and explanations for a lot of his changing guises, and Oldman’s characterisation changes with each, offering grossly hammy flourishes, particularly in the first third. Coppola makes the Count and his environment so archly bizarre it’s a wonder Harker doesn’t run off screaming at first sight, and the film’s early portions offered a wealth of material to satirists, from Dracula’s independently gesturing shadow to his amusing hairdo, which the likes of Mel Brooks and The Simpsons have since made a meal of. Within moments of arriving, Dracula is waving a sword at Harker and ranting, lapping Harker’s blood off his razor blade, and delivering the famous “children of the night” with overblown camp relish. Indeed, whilst Coppola’s editing, special effects, and camerawork are all remarkably energetic, on closer inspection, it’s hard to miss how flatly and poorly directed most of the interpersonal scenes are. Then again, there’s only so much anyone can do with dialogue like this:

Mina: Can a man and a woman really do that?

Lucy: I did only last night!

Mina: Fibber! No you did not!

Lucy: Yes I did…well only in my dreams. Jonathan measures up, doesn’t he?

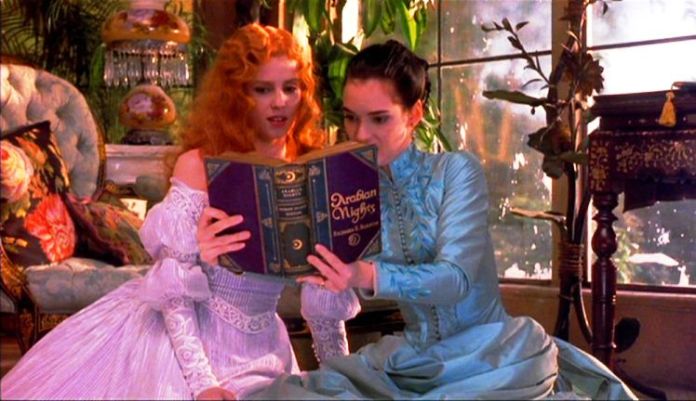

What is this, Carry On Dracula? Coppola aims straightforwardly to explicate the coded sexual elements in the novel. Dracula’s brides are pure carnal fantasy, sucking Harker’s blood and bodily appendages. Lucy, rather more the flirt in the book than the prim Mina, is here completely reconfigured into a budding tart happy to toy with her three suitors whilst pining for sexual acrobatics, giggling and wondering with Mina over the ancient erotic Oriental illustrations in Richard Burton’s translation of Arabian Nights. How exactly two well-brought-up young ladies got hold of such outré material isn’t made explicit, but it is a cunning introduction to the peculiar way the Victorians vicariously partook of erotica through the mystique of the historic and the Orient. When Dracula arrives on English shores in wolf form, he makes directly for Lucy’s house and bangs her in werewolf form in her garden, after she and Mina have been dancing in the rain and kissing in overripe ecstatics. Theoretically, this should be tremendously cogent and subversive in the fashion of some of the originators of the erotic horror style, but instead it mostly comes across as try-hard. A real problem is that Coppola goes to no effort at all to invoke a proper sense of repression and reaction, as Fisher, in particular, realised so beautifully. Coppola’s all-encompassing stylisation, which at many points starts to resemble a Dracula-themed video clip, numbs the narrative imperatives. Seward and Van Helsing are reduced to druggie weirdoes as crazy as anyone they treat. Seward is even seen injecting morphine, and his asylum suggests Peter Brook’s Marat/Sade crossbred with the pastiche of Terry Gilliam.

Like Basic Instinct, with which it shared a high-water mark in mainstream Hollywood’s embrace of the adult in 1992, there’s something amazingly asexual about the sexiness on screen, with Frost’s Lucy lolling on a bed with her boobs constantly falling out leaving a desultory flavour. Amongst Coppola’s fragments of visual rhapsody, bobbing corpuscles are a frequent motif, perhaps underlining why some thought of the film as a metaphor for AIDS, especially with the tale as sexed-up as this. Most crucially, placing a sentimentalised love story at the story’s heart basically smothers the erotic anarchism in the cradle. The clear dichotomy here, between Dracula’s predatory intentions and exploitation of Lucy’s desires to make her a ready victim, and his wanting to win over Mina through more traditional romantic means, is silly on several levels. After a meet-cute on the street, he’s giving Mina candlelit dinners, encouraging her to cuddle a white wolf, and swapping heavy sighs. This mocks the film’s own provocations by reducing the matters at stake to a lust-vs-love dynamic. When the time comes for the text’s key moment of Mina drinking Dracula’s blood from his chest, which is supposed to possess a queasy mixture of coercion and forbidden indulgence, Dracula gets all conscientious: “No, I do not vant dis!” he declares, against the grain of everything the character stands for, only for Mina to insistently drink, with Oldman contorting as if receiving the world’s greatest blow job. Secondly, there’s no subsequent substance, hysteria, or passion to the tug-of-war between Dracula and Harker for Mina’s affection, as Coppola rushes through the latter stages of the story, and never achieves the kind of poetic dissent Rollin’s films could muster.

The final impression, which left me so seriously irritated all those years ago and for reasons that have since become all too clear, is of a film that’s identifiable as a significant step on the route to the tedious Twilight-isation of the vampire mystique. Another thing that’s hard to get around is the fact that Bram Stoker’s Dracula is barely effective as a horror movie. Corny gore and make-up effects are aplenty, but there’s no coherence of mood or eeriness to the proceedings. Apocalypse Now sports a far firmer sense of dread and building metaphysical menace. Instead, Coppola trucks in some of his visual fixations, like cross-cutting between action and a religious ceremony, with lingering views of classical ceilings and religious icons, and bleeding crosses that heal, suggesting a Catholic-porn edition of the story. That the film is visually impressive and occasionally awesome is easy to concede. Coppola builds certain sequences to crescendos, and there are some excellent set-pieces that display Coppola’s sense of sheer cinematic movement, particularly a quality piece of swashbuckling when the heroes battle Dracula’s Magyar serfs. Coppola takes the epoch in which the story is set as an excuse to explore the evolution of cinema itself, from magic-lantern shows through to the flicker of the nickelodeon, one of which Dracula and Mina visit, to the stylised expressionism of Murnau and Lang, the lush artifice of the Hollywood back lot, and on to the most advanced swirl of technical effects.

And yet the effect, whilst bracing for movie buffs, leaves the movie perched uneasily between mainstream storytelling prerogatives and the world’s most elaborate student film. In this regard, it strongly resembles Coppola’s fellow haute-cineaste Martin Scorsese’s version of Cape Fear from the year before, and likewise is a good candidate for Coppola’s worst film. So many moments are conceptually arresting, and yet fumbled in execution and in relation to the overall drama. There’s a suggestion throughout, especially when Coppola cuts from Lucy’s beheading to a rare roast beef being carved, that he wouldn’t have minded turning it all into a Monty Python-esque spoof, and Hopkins’ Van Helsing certainly seems pitched on that level. He suggests a savant, introduced stating that “civilisation and syphilisation have evolved together,” detached from regular humanity. “Yes she was in great pain, and then we cut off her head and drove a stake through her heart and burned it, and then she found peace,” he airily declares when Mina asks how she died. His moral determination is seen as based in his own erotic divorcement, and is himself momentarily tempted, when Mina kisses him in the throes of vampiric urges. But again, there’s not enough firm engagement with this notion to make it seem more than another failed aspect, and Hopkins’ simultaneously hammy and distracted performance doesn’t help.

By the conclusion, the number of things Bram Stoker’s Dracula is trying to be has piled up like a mass car wreck: revision, send-up, ardent romance, film studies class, homage, spooky tale, action flick, disease parable, soft-core porn. But the aspect of Bram Stoker’s Dracula that finally wounds it beyond repair is the endemic woeful acting, from Reeves at his most wooden in impersonating an English gentleman to Hopkins, Ryder, Elwes, and Oldman all offering uncharacteristically poor work. Reeves’ worst moment is his one attempt to get emotional, screaming in terror when he sees Dracula giving over the baby to the brides. I would go easiest on Ryder, who was still making the shift from teen starlet to leading lady, and she acquits herself with flat competence until that scene with Van Helsing, where she suggests less a moral woman giving in to demonic impulses than an interpretive dance student giving in to her inner tart. It is worth noting a brief appearance by future star Monica Bellucci as one of Dracula’s brides, and a cameo by Jay Robinson, once famous for playing Caligula in The Robe and Demetrius and the Gladiators, as Harker’s boss. But the actor who comes off best is Waits as Renfield, essaying physically one of the grotesques Waits usually conveys vocally in his music: he wields exactly the right stylised blend of mordant humour and perverse ferocity. Likewise, Wojciech Kilar’s terrific music score and Michael Ballhaus’s cinematography lend the film much more authoritative heft than it actually deserves. It wasn’t, however, a complete waste of time for Coppola, for some of his motifs and effects crop up again, infinitely more controlled, in his extraordinary return to mythological filmmaking, Youth Without Youth (2007).

This film had me laughing for days after I first saw it. I think it was, at the time, the worst film I had ever seen. However, nothing would have induced me to sit through this ludicrous pile of old tosh again. So thank you for watching it again so I never have to.

LikeLike

I havent’ seen this in many years, but this was the favorite film of an Irish-Catholic fellow I knew. He had a thing for Ryder and watched the film at least 20 times during the time I knew him. I remember enjoying Ryder and the visuals, but everything seemed so Rococo – ornamental but kind of tepid and meaningless. I think your review is dead-on.

LikeLike

Hi Helena. I know what you mean; it took me something like thirteen years before I dared watch it again. I keep wondering if it’s gotten better with age and as my aesthetics evolve, but I can’t say it does, only that I’ve become a little more tolerant of its flaws, because then it was only five years between viewings. In many ways this is a film I feel I should love, a conceptually whacko, boundary-pushing stylistic revision, but it’s just…so…silly.

Mare, my only real problem with Ryder is that she was still audibly having trouble suppressing her American accent, so that she sounds very stiff often throughout. If she’d been a bit more practised, say after her work on The Age of Innocence and The Crucible, she’d have knocked the part out of the park, because she’s well-cast. Rococo is a very good word for the work as a whole. I can see why an Irish Catholic would go nuts for it. As I said, it’s practically a Catholic porn film.

LikeLike

Rod – I don’t remember her accent, but I’m sure you’re right. I’ve found her an uneven actress in her early films, and this was the first one in which I felt I saw her potential. I think she’s brilliant in The Age of Innocence, maybe her best film, and was sad to see her reduced to an hysterical cameo in Black Swan.

LikeLike

Mmm, Catholic porn… er… what I meant to say was, I need to see this again at some point, cos I only saw it once on TV and only have dim memories of a somewhat stifling production design and atmosphere, though I seem to recall liking it too. Wondering what a second viewing will hold, though…

LikeLike

It’s interesting, Mare, that we both think highly of Ryder in The Age of Innocence when it’s become a popular punch-line for many others – I reference specifically, although it’s not the only jibe I can recall, a gag on Family Guy – as that a sort of sacrificial lamb performance for Gen-X-ers to make fun of their idol. I did keep thinking about Black Swan when watching this film, because Ryder would have been a natural choice for the lead role in that film if it had been made in ’92. And, like this film, it shares a certain overwrought daring and clunky result.

JR: Yes, calling Catholic porn does perhaps make it sound juicier than it really is. “Stifling” is a good word for this too. It’s interesting how so many people seem to have resisted watching it more than once. Still, I challenge you to watch it again!

LikeLike

“Another thing that’s hard to get around is the fact that Bram Stoker’s Dracula is barely effective as a horror movie. Corny gore and make-up effects are aplenty, but there’s no coherence of mood or eeriness to the proceedings. Apocalypse Now sports a far firmer sense of dread and building metaphysical menace. Instead, Coppola trucks in some of his visual fixations, like cross-cutting between action and a religious ceremony, with lingering views of classical ceilings and religious icons, and bleeding crosses that heal, suggesting a Catholic-porn edition of the story. That the film is visually impressive and occasionally awesome is easy to concede. ”

Fine points here. I’ll admit I like this film more, but I never saw it as any kind of a horror masterpiece. The visual compositions, that spectacular and harrowing opening and Wojtech Killar’s extraordinary score are what stand out mostly for me today.

LikeLike

Hi Sam. No, definitely no horror masterpiece, which is galling because it was a project with so much promise. But some of the visuals and the score are indeed easy to love. Kilar ought to have gotten more Hollywood work after this, for his score is far from the ponderous hackwork so many other composers trying for this kind of titanic sound usually offer.

LikeLike

The reincarnation/lookalike angle is Dan Curtis’s major contribution to the vampire genre, a device he used on the Dark Shadows show and in his version of Dracula, starring Jack Palance, from 1973. Curtis probably got the idea from The Mummy, and Coppola probably got it from Curtis. The writers of The Mummy, it has also been said, probably got it from H. Rider Haggard’s SHE.

C0ppola’s movie is a guilty pleasure, I guess. It’s definitely style over substance for me, though no apologies are necessary for Kilar’s score, one of the very best of the Nineties. The film wouldn’t seem half as good without it.

LikeLike

Hi, Sam W: Yeah, I’d heard that the notion was first employed by Curtis, although I haven’t seen his version. It’s certainly a result of that ’60s era fondness for delving into the backgrounds of popular culture and mythology. It’s worth noting that I’ve heard Hart’s script was initially intended to be a TV movie, so it’s possible the likeness to Curtis’ is less than incidental, as a remake of a remake of a remake.

As for the relation between The Mummy and She…meh. I can see what they’re getting at, but I think it’s actually drawn from Conan Doyle’s The Ring of Thoth, of which The Mummy is a plain rip-off.

As for style over substance, I’d only argue that the interesting thing here is that, to a certain extent, the style is substance, for some of Coppola’s refrains and visual suggestions imbue the story with dimensions the script doesn’t carry, like the references to silent film and the way this elucidates the interplay of science and mystique, history and immediacy.

LikeLike

Nice review, I agree with everything except one thing – I liked the movie, the visual flourishes and the creepy atmosphere were enough to win me over. I think you make a very good point about Dracula’s constantly changing appearance not giving the character a clear focus, something that may have nagged at me a little without realizing it until you pointed it out. Reeves as usual is not very good, and this is maybe the only movie where I felt Hopkins didn’t quite know how to approach the character he was playing.

(THe Simpsons episode was great, almost the first thing I thought of when I saw your review)

LikeLike

“and likewise is a good candidate for Coppola’s worst film. ”

Nah, that would be, hands down, JACK. What a horrible, awful film – a career low for Coppola. I actually love Coppola’s take on DRACULA for the overblown cheese-fest that it is if only because the style – the camerawork, set design, art direction – is just so gorgeous, so rich and textured that I’m willing to forgive the many glaring flaws.

I also like Anthony Hopkins in this film. He and Tom Waits seem like the only actors who know what kind of film they are in and go for it. Hopkins, in particular, chews up the scenery with particularly relish complete with outrageous accent that always brings a smile. And I will cop to being a Winona Ryder apologist. Daft accent aside, she’s pretty good and the way she moves in this film reminds me of what Scorsese said of her that she would’ve made an excellent silent film star.

LikeLike

Well Rod, I definitely agree with your last statement about how the style Coppola attempts to incorporate here works far more successfully in Youth Without Youth, which I still think was an overlooked masterpiece. That being said, I like Bram Stoker’s Dracula a lot. Since I haven’t read Stoker’s novel, you’re probably at an advantage over me in that department, but from what I’ve gathered of the other versions I’ve seen of Dracula I’d probably charge that most of the problems with Coppola’s film are due to the utter shapelessness of the story itself.

After all, has anybody ever really cared about characters as thinly-drawn as Mina and Jonathan Harker? I’d be surprised if anybody did. No matter how many versions of Dracula I’ve seen–whether it be Murnau’s Nosferatu, Browning’s Bela Lugosi vehicle or anything else–I always find myself fairly bored with Mina, Jonathan and the other “normal” characters. For me, the story only holds up because of its three most eccentric characters: Dracula, with his utter depravity; Van Helsing, with his radical vampire-hunting tactics; and Lucy, with her uber-sluttyness. Everything else I could care less about. But there’s no way I could possibly dismiss a film in which a fanged Sadie Frost sits up out of a coffin and then spews a volume of blood straight into Anthony Hopkins’ face. I mean, come on, admit it: that’s a memorably visceral, disgusting image.

To me the movie is far, FAR from Coppola’s worst film. As J.D. mentioned, Jack is a much more appropriate candidate for that title. And I also prefer it to several of Coppola’s 80’s flicks–I find it to be a much more exciting slice of pure cinema than the likes of The Cotton Club, The Outsiders and Tucker: The Man and His Dream, which are all fine films but, at the same time, feel like underachievements if judged on Coppola’s terms. And as a horror film, I way prefer Bram Stoker’s Dracula to to the likes of Dementia 13, a film so wooden and so incomprehensible (typical of Roger Corman) that I’ve almost completely forgotten the specifics of the plot.

I wouldn’t say the film is badly acted, either. Oldman, Hopkins, Sadie Frost and Tom Waits (whom you’ve acknowledged, I know) all have a lot of fun with their performances. Winona Ryder and Cary Elwes don’t do as well, but this, again, might be more due to the weaknesses of their characters. As for Keanu, everybody complains about his embarrassing miscasting, but I find his bad accent and his whiny fits to be enjoyably campy. After all: who ELSE do people think of when they think of Jonathan Harker these days? (and no–Peter MacNicol in Dracula: Dead and Loving It doesn’t count!)

I think what keeps me returning to Bram Stoker’s Dracula over and over again is the sheer amazing outburst of gore, sex and foulness that Coppola uses at his disposal in order to pump Stoker’s characters with life. Even though Murnau’s Nosferatu is probably the best version of Dracula we’ll ever see (since it was almost totally about the vampire himself, and kept the other characters to a minimum), I like how Coppola’s version is sort of like its polar opposite. I’m not sure a perfect narrative could have been composed out of Coppola’s twisted filmmaking methods, but then again I don’t think that’s what he was interested in doing.

LikeLike

Great review Rod. Though I agree with many of your points and came out of the film disappointed, unlike my brother and another friend, I’ve always appreciated the sheer cinematic bombastic with which it’s told. Style over substance, unfortunately. Had he worked out the human dynamics and then applied the visual ingenuity, it could have been terrific. In this way, it reminded me of Scorcese’s ‘The Age of Innocence’ – decked out with cinematic tricks but not involving me with the human drama at all (unlike say something like ‘The Crucible’) .

Of Coppola’s ’80s work, ‘Tucker’ and ‘Peggy Sue Got Married’ I’ve always loved.

For Dracula film adaptions – nothing comes close, for me – to the chilling effect that the BBC’s 1977 version has had, with Frank Finely as Van Helsing and a magnificent Louis Jordan as the Count.

LikeLike

Thinking about it, Coppola’s film seems like a rather hip, culty graphic novel that fell to pieces once it made it into film and people actually had to say the words. As a graphic novel the post-modern doodaddery would have worked just fine. Readers wouldn’t have had to hear Sadie Frost and her awful squeaky Estuarine voice (can I just say, Bonnie Langford with bozooms.) But taking up Adam’s joy at Sadie throwing up all over the place, it’s a bulaemic sort of movie, gobbling up ideas and influences and then … well, you know the rest.

LikeLike

Bobby – I agree with you about Count Dracula, and my review of it is here.

I do not agree about The Age of Innocence. I think it is pitched perfectly for an Edith Wharton-based tale, and Ryder’s performance offers the exact characterization Wharton wrote for May. Rod’s review of the film is here.

LikeLike

Well, Adam, you probably then shouldn’t comment on what you haven’t read. Yes, Stoker’s story is a little ungainly in places, but it’s a very well written book and the characters, even the goodies, aren’t nearly as thin as is common practice in Victorian genre literature. Even allowing that Dracula, Van Helsing and Lucy really drive the story, and they do, it then does not behoove filmmakers to reduce them idiotic caricatures as is done here. If you can’t tell how badly acted this film is, I really suggest you knuckle down to finding out what acting is. Reeves’ and Elwes’ bad performances are nothing to do with their characters. Line delivery and expressiveness are entirely separate things to the characterisation, and both of them are wooden and terrible. That “memorably disgusting image” is a cheap Exorcist shout-out and frankly just embarrassed me. This film is a real test case for those who can tell the difference between inspired experiment and rampant mess, and frankly such cheap attempts to defend it by trashing the source material is ignorant and insulting.

“Typical of Roger Corman”. Obviously you don’t know much about Roger Corman, either.

Having not seen Jack, I can’t make any comments there myself, although that seems to be consensus as Coppola’s nadir.

“Bonnie Langford with bozooms”. Harsh but accurate, Helena. I couldn’t agree more with your graphic novel analogy.

LikeLike

Though the BBC’s Louis Jourdain version (painstakingly adapted by Gerald Savory, inventively directed by Philip Savile) sticks the closest to Stoker, I’ve a lot of respect for Jimmy Sangster’s Hammer screenplay for the way that it largely honours the novel while sidestepping its narrative flaws. Stoker’s Borgo Pass ending hardly works on the page, let alone the screen, whereas the fight to the death with crossed candlesticks gives us one of the great moments in popular culture.

I remember finding Coppola’s version a dismaying mess.

LikeLike

I very much agree, Stephen.

LikeLike

My problem with the film isn’t the acting, or the directing, it is the basic conception: Dracula in Stoker is EVIL, his seductions are closer to rape, and his intellect is that of a criminal mastermind (a supernatural Moriarty if you will; there have been some good Holmes/Dracula meetings in fiction) . Mina is dominated by Dracula, but she never loves him, and the romance in the film is as far from Stoker as you can get.

I think Hammer’s Horror of Dracula (or in the UK, just Dracula) remains the best film version, but a true Bram Stoker’s Dracula remains to be done.

LikeLike

It is, as Rod says, the beginning of the Twilight-ization of the vampire myth in movies.

LikeLike

Rod, in fairness, I should have been more specific with that Corman comment. I admire Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe movies, but I do hold the opinion that after he submitted to his exploitation phase and had those promising directors taking over for him, the stories he was started to endorse did, indeed, tend to get uglier and more incomprehensible as the years went by. How does one critique a film as pointless as Boxcar Bertha? John Cassavetes once told Scorsese after he made that film that he had wasted his entire year making a piece of shit.

Yes, Corman is obviously responsible for the careers of so many great filmmakers (and I weon’t forget that he also helped Bergman and Fellini get their movies made), but what is so significant about Dementia 13? For whatever reason, that movie has a girl strip to lingerie, dive into a lake and then get chopped by an axe murderer–why she ever dove into the lake in the first place is never even explained. Coppola and Corman reportedly argued a lot over the final cut, and it shows–that movie has no singular vision whatsoever. This is where Bram Stoker’s Dracula feels superior: it’s Coppola’s film in every sense of the word. And although Coppola made some good films in the later half of the 80’s, I don’t think audiences knew that he still had it in him to made a film this audacious or bold. And while I enjoy The Godfather Part III, it doesn’t take as many risks as this film. It’s what we would have expected from Coppola. But Dracula was proof that the lion could still roar.

Regarding Reeves and Elwes, I don’t think the latter is particularly bad in the film. His character is uninteresting, but under the circumstances he does fine–I do believe it’s a painful moment when he finally has to drive that stake through Lucy’s heart. The reason why I don’t mind Reeves’ performance, either, might stem from the fact that it’s become a legendary performance in its campiness. Even with that hilarious accent, I wouldn’t say it’s any less awful compared to some of the other stuff Reeves did in the 90’s (like Point Break, or even Speed). Maybe if Reeves had stopped being an actor after the 90’s I would find his performance here to be much less tolerable. But in the age of the Matrix movies, I’ve come to accept what’s known as the “Keanu role” in movies, which is why I find his Dracula performance more entertaining than annoying.

Again, I haven’t read Stoker’s novel, so I’m at a disadvantage there. But are characters like Mina, Jonathan, Quincy, etc. any more interesting in the book? I don’t think it’s ignorant to say that a film can be great even when it’s compromised by some of the weaker aspects of the source novel. I think To Kill A Mockingbird, for example, is a terrific film. But there are parts of Horton Foote’s screenplay that contradict the message of the story–a blame that we might be tempted to put onto Foote until we realize that Harper Lee’s novel was guilty of the same crime. Sometimes movies are faithful to the books in ways they shouldn’t be. I even feel that way about the Coens’ True Grit.

How are the characters in Stoker’s novel any richer than they are in Coppola’s film? I’m just curious. You say, “the characters, even the goodies, aren’t nearly as thin as is common practice in Victorian genre literature,” but that doesn’t really address the issue at hand. My point is that the big flaws in Coppola’s film are mostly character flaws–flaws I suspect the Stoker novel was also guilty of, and which Coppola probably should have fixed with his film. But the other stuff that you criticize in your review (the excessive gore, sex and all-around frenzied filmmaking) makes up exactly why I find to be so exhilerating about Coppola’s technique.

LikeLike

I always enjoyed this movie. But then, I guess I often enjoy trash, whether it’s movies or food.

LikeLike

Indeed, and like everything else, even tastes in trash are individual.

LikeLike

My good friend, David Stone, won an Oscar for sound editing on Dracula. Sure, the film was over the top, but technically it was incredibly well-crafted.

LikeLike

I would personally applaud Mr Stone’s Oscar. The sound is certainly excellent. Although one of my fellow internet blog critics complained to me that the sound made when Vlad is impaling a man at the start sounds like a fart. I have no opinion on this.

LikeLike

Total Camp!! The kind I love ’cause you can give Anthony Hopkins a crazed, lunatic appearance with lines designed to make you want a barf bag handy if you’ve a vivid imagination and still appreciate Winona Ryder for the obvious fun, like in Sleepy Hollow still another campy treasure, she has with it all! I realized from the very beginning with the comparison to Vlad this was going far away from the 1897 many times told tale and into a delicious realm of maniacal rants and over-the -top costumes. From the moment I saw ‘woody’ Reeves departing for the castle I was titillating with delight…how far apart could he fall for us, the audience without drawing out a guffaw? This ‘seriousness’ was the most important part to me, give me a good rowdy bit of camp without making it silly. Make it look on the surface like it takes itself seriously…and it did for the most part carry that off perfectly. CAMP that’s what it was to me a really fine bit of something very hard to do , harder still to recognize and appreciate! If you came looking for horror, sorry it’s CAMP here!!

LikeLike

Frankly Shane I don’t find it funny enough to enjoy as camp; rather it strikes me as desperately trying to be camp in places and failing..

LikeLike

For a 1992 environment of young gothic/metal fantasyroleplayers this film was a sort of revelation.

The film poster appeared in everyone´s room (soon followed by Interview with a Vampire + The Crow).There are obviously many reasons for thrashing it or enjoying the camp but remember this was just at the beginning of the multiplex era and it was epic.

I agree with everything said about W.Kilar, the score and the sound.Most people liked Winona Ryder -and the 3 female vampires.

I simply felt cheated. This was not Dracula.

Films were important these days. Me and a friend discovered same year´s Braindead. A film poster that looked gorgeous on anything – and a far more romantic love story.

LikeLike

I get where you’re coming from Maren – I remember how Interview With The Vampire and The Crow became the next big Moody Young Thing icons too. Yes, Brain Dead is a far far better film.

LikeLike