Directors: William Friedkin / John Frankenheimer

By Roderick Heath

It’s 40 years now since The French Connection was released, soon to capture the Best Picture Oscar, set up William Friedkin as a directorial talent with the world before him, and make Gene Hackman a top film star, pushing age 40. From such a distance, during which time the film’s status as a classic has wavered and Friedkin’s career has never quite lived up to its great early promise, now the cultural bullseye The French Connection scored seems ever more peculiar. Not simply in that it’s a crime flick, not a prestigious genre, lacking the epic pretensions of The Godfather which would win similar garlands the following year, but also in the rich yet radical, machine-like beauty of its filmmaking, the eerie disquiet of its ending, the oft-ugly ferocity of its pig-faced bog Irish cop hero, and tangible atmosphere of then-decaying New York. The two French Connection movies are coarse, bloody, rapidly paced, unswerving and experiential rather than analytical. The first entry is a police procedural that seeks for the most part to clearly, intricately, and excitingly describe a fictionialised version of one of the biggest drug busts in history, with as much nuts and bolt detail about both smuggling and policing as any film ever made. Lacking big stars, romance, moralising, and even much action except in the central, ever-impressive chase sequence, The French Connection brutally contrasts much popular filmmaking today, and Friedkin’s film and its sequel by John Frankenheimer constitute summits of mainstream American cinema.

Friedkin’s film, moreover, always strikes me as a different movie each time I watch it. Initial viewings are almost a sensory overload: there’s little that is overtly tricky about Friedkin’s filmmaking, but the depth of his reliance on visual storytelling, the alertness to environment, to detail, to nuance of behaviour essayed at such rapidity, infuse the screen with a lustre that only seems to increase as time passes. With repeated viewings the potency of Friedkin’s conception of Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle’s cat-and-mouse game with drug kingpins as a form of class warfare jumps out at me. Anti-drug messages were big at the time of the film’s production, in the waning phase of the counterculture and the onset of the Nixon-era mood of social depletion, and that possibly gave The French Connection the right gilt of nobility to swing its Oscar victory, whilst it was in line with the short-lived affection for gritty fare inaugurated by Midnight Cowboy (1969). Nonetheless, it’s fascinating how little The French Connection is actually about the white powder over which lives and punishing effort are expended. The only user seen in the film is the slick-mouthed long-haired chemist (Pat McDermott) who tests the purity of the imported heroin for a small amount of it. Yet the junk seems indivisible from the snatches of blasted and sorry suburbs of the city, filled with urban decay, cheerless wintry wastelands, and infested with small-time dealers, which Friedkin describes with chilling efficiency throughout. In this vision of a contemporary American metropolis, white cops beat hell out of black dealers in scenes of predatory flushing and catching of the prey, yet there’s a pall of certainty around both sides that they’re both stuck inhabiting the same wilderness, fighting on the level of primitives for the scraps society is casting down their way.

Popeye and his partner Buddy Russo (Roy Scheider) have the best arrest record in their department, but they’re all too acutely aware, as their superior Simonson (Eddie Egan) reminds them, that in essence their labours are petty and ineffectual. But then, after a bust that sees Russo get a slice on the arm and the perp (Alan Weeks) angrily knocked about and bullied, the two retire to an up-market tavern for some R’n’R, only for Popeye’s raptor-like eye for criminality to zero in on a gathering of underworld figures out wining and dining their women, including Sal Boca (Tony LoBianco), tossing around money. Popeye talks Russo into following them about, and eventually they’re stunned to find that Sal returns early in the morning to his teenaged wife and a tiny diner business. Popeye is immediately convinced that Sal is connected in some serious fashion, and he’s dead right. Sal is arranging the Stateside end of a massive heroin deal, of junk being supplied from Marseilles by Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey), which will be brought into the country inside a Lincoln Continental by French TV star Devereaux (Frederic de Pasquale). Popeye’s convictions are patronised by his senior and by FBI agent Mulderig (Bill Hickman) attached to the case. The past, which involved the accidental shooting of a fellow cop, dogs Popeye as wickedly as the hangovers he nurses each morning after drinking himself stupid. But the team’s work begins to pay off when Charnier and his pet thug Nicoli (Marcel Buzzoffi) arrive in town to make the deal, and they link Sal to Weinstock (Harold Gray), a financier for traffickers, whom Sal is trying to get to invest in the deal.

Although it’s most certainly not a documentary, The French Connection gains a lot of its pep from practically neo-realist elements. Those include the casting of non-professionals like the real-life analogues of Doyle and Russo, Egan and Sonny Grosso, and Irving Abrahams, who plays himself in the car-stripping scene. The immersive vision of a gritty metropolis offers glimpses of men lying sprawled on the pavement, filth-crusted subway tunnels, and camerawork in the street where it’s clear the crowd, constantly glancing at the camera, aren’t extras. The film probably gave Scorsese some permission to explore his city in similar fashion with Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976). The method Friedkin adopted, with his toey but unaffected handheld camerawork in many scenes, lends physical energy to the essentially observational sequences, whether they’re about Doyle and Russo trying to eat whilst freezing their asses off on a surveillance job, or, most memorably, the sequence in which they strip down the Lincoln in which they think the shipment has been hidden, bringing to the fore the amazing amount of empty space in such a seemingly solid car, and the increasing frustration of the cops as they fail to find anything before Russo’s observations about the car’s weight lead to a sudden, successful realisation. A peculiar quality of The French Connection, one that its sequel shares, is that it’s a beautiful-looking film, with Owen Roizman’s photography absorbing colour in variegated patches that come to resemble a Rauschenberg artwork. An arsenal of New Wave tricks, from zoom shots to disjunctive sound and vision, sees the film accumulate in layers, offering an aspect of raggedness that conceals the great filmic talent at work behind it. That talent is clearly at work in the dance of actors and imagery in Popeye and Charnier’s amusing hide and seek in the subway, in the cold-blooded assassination Nicoli commits after the deceptively ambling opening shots (complete with tearing off a hunk of his victim’s bread loaf), and of course at a much higher volume in the chase scene and the violent finale.

The French Connection’s monomaniacal bent in sticking almost purely on the matter at hand is often why it’s been discounted as a simple cop flick by many over the years, and yet I feel it’s precisely there where its greatness lies, in refusing to linger on extraneous detail or pompous presumptions of socio-political and aesthetic import, whilst still concisely evoking them. Early in the film, when Popeye and Russo visit the tavern in which they first make Sal, The Three Degrees, a black girl group, croon lyrics that point neatly to the irony that this generation, sending rockets to the moon, is also the one living in decaying tenements, beating hell out of one-another, and stuffing drugs into its veins. Otherwise the context is simply there to be read, in the lives its heroes lead and those of the villains. Popeye inhabits a boxy little apartment in a grim tower block, and the only pleasures he gets are liquor and sex, at which he’s fortunately adept at getting, as when he picks up a bicycling girl, cueing the film’s lone islet of bawd as Russo, coming to Popeye’s place to talk over a new development in the case, finds him handcuffed to his bed and the girl still darting naked about the flat. But life is otherwise not much fun for these guys, and Friedkin makes a marvellous, almost Chaplin-esque visual suite out of the scenes in which Doyle and Russo try to cram their faces with pizza and terrible coffee whilst Charnier and Nicoli dine in a ritzy restaurant. Whilst Popeye’s behaviour demands tempering empathy for him with wariness of his fiery brutality and racism, here the pendulum shifts his way: you can practically feel Doyle’s white-hot antipathy in Hackman’s grimace as he watches the pair, not only a personal resentment owing to his own working-stiff righteousness, but in the already clearly conceived detestation of people who are getting seriously rich by eating out what’s left the fabric of his city and world.

Daryl F. Zanuck warned Friedkin that if the film wasn’t done right, he’d end up with a glorified The Naked City episode, and Friedkin’s answer to that was to invest Popeye with his voluble ambiguity; by turns, Popeye, with his signature pork pie hat and trenchcoat, is a swashbuckling hero and a scary prick. His maniacal dedication to the case at hand is both his great virtue and great weakness, blind to other matters, whether it be mangled car wreck victims in a scene where he comes to blows with Simonson and Mulderig, and finally accidentally gunning down Mulderig in the finale when he’s chasing Charnier, barely blinking when he and Russo discover the mistake and keeping after the villain. That closing moment is one that Friedkin shoots in the environs of the ruined warehouse where the drug deal was going down, and through which Popeye dashes off, as if he’s disappearing into an existential void in keeping after Charnier, emblem of a world beyond his grasp and comprehension. I suppose it could be said that the great chase sequence that is the film’s centrepiece betrays the texture of the film’s realism, but of course it’s also the bit you look forward to, as the eruptive elegance of Jerry Greenberg’s editing and the brilliant shooting of Friedkin and Roizman converge here for a masterpiece of its kind. The chase starts when Nicoli makes an ill-fated attempt to rub out Doyle, recognising that it’s his drive that is sustaining the threat to the deal. Nicoli instead finishes up plugging a carriage-pushing mother and a railway guard, driving a train driver to have a heart attack, and causing a train wreck, as Doyle all the while chases at high-speed through busy streets in a commandeered car. The hood-mounted camera shots of speeding motion through the streets giving the sequence its sense of hurtling doom, and the sequence resolves with brute frankness as Doyle plugs Nicoli in the back when he tries to run. Other cops objected to this touch, but Egan gave Friedkin the nod to include it: even in adding some pizzazz to the film, the integrity of its unromantic take is retained. Scheider, who was cemented in the cinemagoers’ mind in ’71 with this film and Klute, is terrific even in playing a relative second fiddle. His peerlessly pronounced retort to Mulderig’s comments about his partner, “Shove it up your ass,” is one of the summits of on-screen profanity.

French Connection II seems at superficial attention to announce some unfortunate aspects of Hollywood’s nascent sequel culture: it was the first major Hollywood sequel to have a simple numeric attached to the title, a touch that was in keeping with the film’s veneer of terseness and yet soon to become a signature of corporate Hollywood laziness. It also moves away from the reportage of the original for a fictional continuation, more dialogue-heavy and melodramatic in form. Yet such descriptions are deceptive, as French Connection II is as good as, perhaps better than, the first film. Friedkin, who had moved on to his other best-known movie, The Exorcist (1973), didn’t return for it; instead John Frankenheimer, the solidly established and lauded hand from the precursor generation of new-style American directors, took over. He retained key aspects of the first film’s style, whilst also refining it and making some innovations of his own. It stands as possibly also Frankenheimer’s last truly great film, for a similarity of both his and Friedkin’s careers was their early brilliance and their shaky later oeuvres. A key linking element of the two films, other than Hackman and Rey, is Don Ellis’ nervy, vibrant scoring, accented with elements of jazz, funk, spurts of musique concrete, and even modernist atonal passages that infuse the cityscapes with alien vibes. The sequel picks up spiritually where the original left off, with Doyle still chasing Charnier, having been sent to Marseilles as the only man who can certifiably recognise him, to liaise with the local detective chief Henri Barthélémy (Bernard Fresson), who treats him with dismissive contempt and relegates him to a desk next to the men’s room door. Popeye doesn’t realise that he’s actually been sent to lure Charnier out, and, worse, he’s really being set up by other cops back in New York whom Charnier bought off, hoping he’ll get killed.

Inevitably, Popeye is a fish out of water in this world, and scenes in Frankenheimer’s film carefully mirror some in Friedkin’s. This contrasts his earlier behaviour and former competence, as when Popeye chases down a suspect running from the scene of a sabotaged narcotics lab, only for Barthélémy and his men to drag him off, because the guy’s actually an informant, underlining the irrelevance of Popeye’s racial assumptions and his inability to recognise the lay of the land he’s so sensitive to back home. Popeye’s head-on policing style in such a circumstance seems doomed to cause havoc, his signature bullying tactics and verbal tirades are reduced to a comedy routine before a laughing, uncomprehending prisoner, and his declarations of determination to nail Charnier seem like so much empty rhetoric. Alienated by Barthélémy, he instead starts pounding the streets in trying to catch a glimpse of his quarry. One night, after chatting up a beach volleyball player (Reine Prat) and being spied doing so by Charnier, he’s kidnapped by Charnier’s thugs, and one of the tailing policemen Barthélémy has on Popeye is run over and killed. Charnier has Popeye kept prisoner in a seamy hotel filled with drug addicts and prostitutes, and pumped full of regular doses of heroin for three weeks, partly to extract what he knows about Charnier’s new operation, which is nothing, and also in a precisely sadistic vengeance on the most implacable of anti-drug enforcers, reducing him to a robotic dependent. Finally Popeye is given a hot dose and dumped outside the police station, and Barthélémy and doctors fight to save his life.

Frankenheimer, who had worked on French location several times before, uses a mostly French crew, including DOP Claude Renoir. The filmmaking team’s eye for picturesque decay invests Marseille with the same mix of lively affection and squalid authenticity as New York received in the first film, with labyrinthine, rubbish-strewn poor quarters lurking behind the ritzy harbour surrounds. If Friedkin’s film has its roots in the docudrama of ‘50s crime flicks, Frankenheimer’s is closer to genuine film noir, and, in a way, can be seen as a stealing back of that tradition from the New Wavers. Such a perspective is implicit in the way the film offers a deglamourized and peerlessly tangible sense of the locale that anticipates, and possibly laid seeds for, modern French crime films like Un Prophet (2009). There’s as much procedural detail in this sequel as in the original, as Charnier’s innovative new smuggling methods, including in tomato cans and on ship hulls, are carefully depicted, but whereas the first film is to a large extent “about” that detail, here it’s more functional within a cohesive, driving plot. French Connection II is more concerned with exploring Popeye’s gruelling journey and penitential suffering, in being almost destroyed by Charnier and his own arrogance, before resurging with (literally) fiery wrath.

Popeye seems initially like the quintessential ugly American in his insensibility to warnings and blithe indifference to local niceties, as Barthélémy needles him into getting on the street. Popeye begins to adapt, slowly: in a terrific early scene, Popeye strikes out with a couple of local ladies but finds a sort of a pal in a bartender (André Penvern) with whom he gets tanked and reels about the streets with, and his capture by Charnier comes after he’s managed to score with said volleyball player, proving he’s still got his mojo working. Meanwhile Charnier has returned to his piss-elegant lifestyle: dialogue scattered in both films suggests that his actual background, in spite of his mansion and purebred young wife, is in the working class and the docklands. He is arranging a new big shipment now with multinational collusion and finance, with the aid of an American General, Brian (Ed Lauter). With its suggestions of wider conspiracies and higher levels of malfeasance, French Connection II subverts some of the presumptions of the original, becoming in effect a Watergate movie in which Popeye finally finds a better working partnership with the Frogs than he did with his own feds.

Hackman had won the Best Actor Oscar for the first film, a deserving win in a strong year for contenders. But he’s even better – perhaps the best in his career – in the sequel, particularly in the lengthy, grinding scenes in which Barthélémy helps him through going cold turkey, a regimen Barthélémy insists on because it would be the end of Popeye’s career if his state becomes a matter of record. We find out things about Popeye here that explain a lot about him, like the reason for his surprising athleticism – he was once a baseball player who instantly joined the cops when he caught a glimpse of a young Mickey Mantle – as well as his fixated intensity, and the despair within him that addiction reveals rather than causes, previously anaesthetised with booze and work, but given free reign by a junkie’s pathos. Hackman’s opinion of his character was low – “Doyle is a fascist,” he said unequivocally, whilst reporting that cops generally loved the honesty of the portrayal – but his reserve against the character’s stridency and cruelty falls away in the sequel. The central, achingly sustained scene of the film comes when Popeye rambles on to an attentive but largely bewildered Barthélémy, who’s guilty at Popeye’s fate and his own not being able to rescue him. Popeye tries to demonstrate baseball moves with chicken drumstick and orange, in between contortions of withdrawal and desperation, struck through with the impossible need for friends and familiar things in going through hell, in a city that just doesn’t offer them, from hamburgers to people who know who the hell Mickey Mantle is. His stay in the hotel, where he’s visited by an aged English addict (Catherine Nesbitt) who soothingly rambles to him about her own past whilst stealing his watch, has a bleak cul-de-sac of the soul atmosphere to it reminiscent of the boarding house in The Seventh Victim (1943), the perfect place for Popeye to be lost in a haze of his failings as well as heroin.

There’s implicit approval of Popeye’s reckless style, and yet another message is quite clear, that if he and Barthélémy had worked together properly from the start, his ordeal could have been avoided, and the last act sees the policemen working together in a purposeful unit. The other actor the two films share is of course Rey, who was reportedly accidentally cast in the original when Friedkin requested “that guy from the Bunuel films”, meaning Belle de Jour’s Francisco Rabal, and the casting agent signed up Rey so quickly there was no time to renegotiate. It was a happy accident, if true, because Rey’s excellence is in how utterly un-villainous his Charnier seems, a dapper and affable man about town whose ruthlessness and cleverness are only hinted at in his insolent little wave to Doyle in the first film, and then revealed in the most specific circumstances. His best moment in the sequel comes when Charnier first spots Doyle in Marseilles, acute anxiety charging his features before resuming normal operations, and adopting a cobra-like chilliness when he later interrogates his cop prisoner. Once he recovers, Popeye embarks on a campaign of purification, fending off Barthélémy long enough so that he can track down the hotel himself. Pouring petrol about the place, he sets it ablaze to drive out the denizens like rats, flushes out Charnier’s goons, and releases his now deeply personal sense of grievance and frustration on the only scale that can satisfy it. It’s a typically outsized reaction from Popeye, but it does work: he gets a lead on Charnier’s new deal. He and Barthélémy almost manage to capture a new shipment where it’s being extracted from the hull of a Dutch freighter in a dry dock. But they barely survive an encounter there with Charnier’s new number one henchman, Jacques (Philippe Leotard), who wields a German army machine gun with brutal aplomb and kills Barthélémy’s subordinate Miletto (Charles Millot), before letting the sea into the dry dock.

Popeye saves Barthélémy’s life when he’s knocked out by a falling spar, and the French cop repays the favour by helping Doyle stay, when his superiors want him kicked out of the country, and acting on Doyle’s hunch, watching the Dutch ship’s captain (Raoul Delfosse), who leads them to Jacques. The cops track him back to the warehouse where they’re able to bust the whole of Charnier’s operation. Barthélémy gains some vengeance when he dispatches Jacques, who, trying to escape with some of the drug shipment in a truck, instead crashes into the warehouse doors Barthélémy sets closing: Jacques is hurled out through the windscreen. Meanwhile, Popeye chases Charnier on foot through the city. Amongst the many felicities of his filmmaking, Frankenheimer engenders the visuals with a sense of physical connection to Popeye, painstakingly portraying the delirium and liquid sense of time and care when he’s under the influence, his attempts to get back in shape after he’s recovered. This pays off in the finale’s lengthy foot chase, the modulated soundtrack and the lunging POV shots conveying Popeye’s exhaustion, so that the audience practically share his burning lungs and aching feet. Inevitably, this sequel risks being more prosaic as it finally gives Popeye the closure he sought, and yet there’s still an existentially gruelling aspect to his chase, running without gaining. It finally resolves in one of the sharpest and nastiest comeuppances in movie history, as Charnier, right on the threshold of again cheating Popeye of his prize, hears his cry from the quayside seconds before bullets smack into his body, and Frankenheimer cuts directly to black. The final effect is both satisfying and chilling, and one of the most perfect endings anywhere.

Incisive review of a pair of my favorite ‘un-handsome’ films – gritty is too soft a sandpaper for these two, much of that due to Hackman’s unstoppable good/bad menace; altho I would’ve preferred the sequel was not that, just it’s own, separate, special thing. I’d read NYPD Chief Seedman’s true crime book, “Chief!”, which had an elaborate insider’s view of the real French Connection, and outside of the absence of the endless paperwork, a few extra baddies, and collapsed timelines, The French Connection is one of the most definitive crime films ever – it has that feel of the hurtling along of a big case and the desperation of all involved. Scheider was excellent, too, and his intensity was on display in such fare as the similar “Seven Ups”, and later in clever “The Last Embrace” among others. I love Rey in these two films, which are actually like two commercial firms headbutting over a stock deal rather than dope, just unrestrained. Rey is like a watchmaker amongst ironmongers, and it works. You hit the nails on the heads again, as usual!

LikeLike

“A watchmaker amongst ironmongers”

Bloody well said in turn, Van the Man. Possibly the filmmakers felt free to go off and do their own thing with the sequel after Badge 373 did the “continuing adventures of Egan” thing; also interesting that in some aspects American Gangster finished up being the Stateside French Connection sequel. The change of locale, too, helped it stand out from the quickly swollen pack of gritty policiers like The Seven-Ups, etc.

LikeLike

As a side comment, I think one film surpasses all others from this period in nihilistic anomie, may have been the grittiest and certainly the most casually sadistic, and more influential than many will admit: “Across 110th Street”, which had a real feel for the decaying NYC that you could almost smell. It was done with broader strokes, but may have been closer to the truth of a lot of criminal and policing endevours, and the acting was nothing short of ferocious, like a cast of all Popeye Doyles.

LikeLike

Rather unfortunately, my one attempt so far to watch Across 110th Street came with a VHS copy that proved so damaged and ill-used that it almost destroyed my old VCR’s heads. Such were the dangers of those days.

LikeLike

Very nice writeup on those to films that made me (re)appreciate some aspects I hadn’t thought about in depth before. It seems also true to me that especially the first film always seems to change with each viewing. It may not be “better” than Frankenheimer’s but it definitely seems more complexly layered – as you also describe it.

But I would like to object to your passing disregard of Frankenheimer’s and Friedkin’s later work, as I think both have continued to make further masterpieces, e.g. “To Live and Die in L.A.” for Friedkin and the fantastic “Dead Bang” for Frankenheimer.

LikeLike

Well, Sano, I like To Live and Die in LA quite a lot, and Friedkin continued to make interesting films now and then, but I don’t honestly think it’s in the same league as The French Connection: too much Michael Mann filching, too much ’80s excess and sloppy touches. Dead Bang I haven’t seen, but I also like quite a few of Frankenheimer’s later works, whilst, again, not finding them in large part up to the quality of his best work. His later TV movies are generally excellent, and Ronin is within shouting distance of his best thrillers, but there’s something missing that could make it stand up with The Train or French Connection II.

LikeLike

Masterful double review of a pair of films that have become part of the cinematic culture, but which alas are dated and less than impressive than the time they were released. Yes, Hackman was superlative (I still believe his performance as the son in I NEVER SANG FOR MY FATHER is his finest in a buffo career) in both films, and his work is still

THE FRENCH CONNECTION’s Oscar win in 1971 was one of AMPAS’ most infamous moments, methinks, as THE LAST PICTURE SHOW -my choice for the greatest film of the 1970’s – and A CLOCKWORK ORANGE was among the short list nominees, but it is typical, since the film was seen as art and as a roller-coaster ride. The chase is expertly done, and the excellent score by Don Ellis remains a high ticket item on e bay on it’s superb Film Score Monthly release.

LikeLike

Err, yeah, I disagree with about 90% of that.

LikeLike

You disagree with the proposition that THE LAST PICTURE SHOW and A CLOCKWORK ORANGE are better films than THE FRENCH CONNECTION?

Or you disagree with the selection made by the Academy, in which case you’d be agreeing with me here.

If the former, well then I am speechless.

LikeLike

I like The Last Picture Show but no, I don’t think it’s better. A Clockwork Orange is great, and so are McCabe and Mrs Miller and Dirty Harry and Sunday, Bloody Sunday. It was a rockin’ year. Any of them winning would have been fair. But that’s the problem with turning movie appreciation into a horse race. And you can be speechless all you want Sam but I made my points about why I think TFC is a great film in my essay and that’s pretty well all I have to say on the matter.

LikeLike

Rod, why this incredible hostility here??:???

Was I not fair and complimentary in my original comment? Am I not always fair and complimentary in every post that I come to here?

This is unfair, and I must protest your lousy attitude.

I wasn’t turning this into a horse race, and I know well what movie appreciation is that you very much!! I tried to generate comparative discussion, and a general segue into 1971 cinema, which is one approach to take when one isn’t overly thrilled with the film being review.

What’s the matter, this wasn’t congenial and complimentary enough:

“Masterful double review of a pair of films that have become part of the cinematic culture, but which alas are dated and less than impressive than the time they were released.”

Did I not acknowledge the exceeding quality of your presentation?

Am I allowed to disagree?

“I like The Last Picture Show but no, I don’t think it’s better. A Clockwork Orange is great, and so are McCabe and Mrs Miller and Dirty Harry and Sunday, Bloody Sunday. It was a rockin’ year.”

Indeed it was. I’ll add:

Les Deux Anglaises et le Continent

The Devils

The Go Between

Love

Walkabout

The Merchant of Four Seasons

Mon Oncle Antoine

Straw Dogs

The Emigrants

Looking back at many of my responses under your reviews both here and in the past at This Island Rod, I saw a plethora of aproaches taken. For some of your reviews I opted to concentrate on the film’s director, for others I marveled at the brilliance and/or eloquence of the reviews, for still others a personal reaction to the film, and yet for others I contrated on theme, social importsnace or other dominaqnt components like acting, cinematography and writing. In some instances I combined some or all of these approaches.

With your review of THE FRENCH CONNECTION (a film I have always felt was grossly overrated and undeserving of the accolades it won, including the Oscar) I opted to discuss 1971 cinema, as I feel the film’s critical reception has always been an overriding bone of contention with me. More infamously fascinating than this dated film, in fact. I acknowledged that you wrote a stupendous review, but just said I wasn’t on board for the film. When I get such a response at my own site I am overjoyed.

When I said innocuously enough ” am ‘speechless’, which is really a nothing word, neutral as they come, you took that somehow as an insult, when all I was trying to do was bail out.

LikeLike

Sam, I do apologise if my defensiveness was excessive; you are as ever my most enthusiastic and reliable commentator, and Sam not being zealous is not Sam. But sometimes I just don’t feel like defending my opinions, least of all when it comes to a film I love as much as this, and whilst you may think “speechless” is a nothing word, from this end it seems anything but; rather on the contrary, it suggests you find my lack of taste robs you of words. I wouldn’t say I was speechless about your preference for The Last Picture Show, for instance, not in a million years; I would save that if you said, oh, Love Story was better than either. On the plus side, yes, that further list of ’71 films is way cool. One of the outstanding qualities of most of these films is the remarkable grittiness they exude, the feeling of what’s tolerable in mainstream cinema being stretched it ways that still feel transgressive.

LikeLike

I just watched The French Connection again yesterday and liked it so much more than when I first saw it in my early teens. Back then I thought it had some nice sequences but suffered from an unfocused structure; now, I think it’s a really, really good movie (I haven’t seen Frankenheimer’s sequel yet, unfortunately, but your review has made me want to check it out.

One thing that struck me while watching The French Connection again is how I actually began to appreciate some aspects of the movie I had criticized during my first viewing a handful of years ago. When I was younger I complained that the movie’s characters weren’t 3-dimensional; now, I wouldn’t have the characters any other way, because we learn as much as we need to about them in the midst of the action.

Popeye and Russo have a harsh way of dealing with people. Charnier and Nicoli are badasses. Sal is uncomfortable with the deal he’s made with the French (incidentally, it was only on this recent viewing that I noticed just how good Tony Lo Bianco actually is in this movie — the only other movie I’ve seen in which I think he has just as much presence is Robert Mulligan’s Bloodbrothers). And Mulderig distrusts Popeye like the plague. In a lesser movie, the bad blood between Popeye and Mulderig would be quickly forgotten by the filmmakers, but when Popeye accidentally shoots Mulderig at the end — BAM! Mulderig’s point that Popeye is a reckless vigilante is rubbed right in Popeye’s face, and Popeye’s lack of emotion just proves it.

So, what’s great about this movie is that there’s so much, in fact, to learn about each of the people in the midst of all the crazy shit going on. Ebert writes that the movie intentionally lacks 3-dimensional figures because “everything is happening way too fast”, which is true, but I think Friedkin just prefers to leave the characters’ personalities understated. Popeye is *nothing* without his job. He’s useless to society whenever he’s off-duty. I hadn’t even thought about the deeper meaning of the song the Three Degrees are singing in the bar, but yeah: that describes the movie’s world perfectly. In another generation, it’d be Sheriff Andy Griffith supervising society’s missions to the moon. And instead we got Popeye Doyle.

The only criticism I still have — one I had when I was younger, too — is that Friedkin’s handling of the ending is a little weird. The final shot of Popeye storming off into the warehouse and shooting frantically at the shadows is so eloquent that I wish we could just cut to the end credits immediately afterward. But instead we get last-minute title cards informing us what happened to all the characters. It’s not that I mind the title cards in general (the movie *is* based on true events, after all), I just wish they had been included somewhere before the final shot, and not after it.

By ending the movie with the title cards themselves, Friedkin is ensuring it so that the first thing on the audience’s mind as they walk out of the theater is the question, “So… did Charnier escape to Paris?” To me, that isn’t even important. Friedkin should have ended the movie right when Popeye disappears into the warehouse (after killing Mulderig) so that the first thing on the audience’s mind is, literally, “Does this mean Popeye’s gone off the deep end?”

LikeLike

Rod, thank you for that. Needless to say I was way too aggressive there, letting the fever of the moment get the best of me. But I knew within thirty minutes after entering my responses that I was acting silly. So I absolutely owe you an apology here.

This entire FRENCH CONNECTION discussion for me was a carry over from last month, when I had a friendly yet heated discussion with a friend, who like you thinks quite a bit of the film. He had seen it at the Film Forum during it’s one week restored print run, and was tot to trot to expound on it’s virtues.

I’ll be the first to admit to you that it is sad that whenever I think of this film, I immediately dwell on it’s Best Picture win over THE LAST PICTURE SHOW. I need to get off that mental silliness.

Anyway, your overall position is more than understandable.

LikeLike

Cool, Sam. Hatchet buried. I know how those conversational carry-overs can work, too. Needless to say, several of the films we’ve mentioned were all big landmarks in my adolescent film education, but damn I do need to see The Last Picture Show again; it’s been ages. If I have a problem with TLPS, it’s that after a couple of viewings it started to bug me how often Bogdanovich falls back on the touch of having some character commence a wistful reverie as he zooms in slowly, for a form of instant nostalgic gravitas. That said, it’s rich and humane cinema and Bogdanovich desperately needs more appreciation these days.

Adam: I agree with just about everything you say, but I don’t have a problem with the title cards. I direct your attention to how Friedkin manipulates this seeming closure so it still vibrates with threat and strangeness, like the terse statement, which Eddie Egan objected to, that Doyle and Russo were reassigned, and the generally lame sentences handed out to the bad guys. It speaks volumes about how what should have been a colossal triumph ends up being a strange and haunting quagmire. In short, the title cards give the end an ironic punch it wouldn’t have otherwise. Indeed at the time, I recall, people like Pauline Kael whined that it was needlessly antiheroic, as if antiheroics can only be served up with real good reason. But indeed, there’s so much in the film that it demands multiple viewings. Look at how cunning the glimpses of Sal and his wife are (and yes, LoBianco is great), like that conversation Russo strikes up with her in the diner; you can hear her flirting mercilessly with him even as the attention of the camera follows Sal as he proceeds about his nefarious business. It’s a haiku of revelatory characterisation for all three, and it demonstrates how carefully Friedkin can use the fleetness of the new wave-y style to enriching effect.

And yes, watch the sequel ASAP.

LikeLike

Finally caught up with the sequel. It’s 3 AM in the morning over here and I’m about to crash, but one thing I should say is I love the comparison of Popeye’s cold turkey to Indy’s Kalimar trance. I knew it felt tonally similar to something (even if it was from a movie released a decade later).

LikeLike

Hi Adam. Hell, when it comes to that, I feel like French Connection II could be the source text for quite a few regulation plot patterns and acts that would become popular in the next 15 years or so, starting with the numerical sequel title and including, yes, the hero going down and then coming back strong (although Kurosawa and Leone had done that before; possibly influences on Frankenheimer in turn).

LikeLike

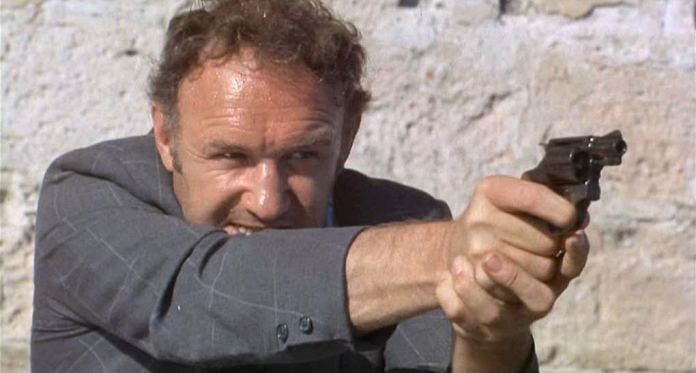

Hey, Rod! (No pun intended.) I stumbled upon your site while looking up articles on FC II, which I thought had been given short shrift at the time. Many critics dismissed it out of hand, without delving into its expansion of the lead character and his struggles in a totally alien environment. I was stunned that it wasn’t nominated for Best Picture, Actor, and Screenplay. But I was absolutely bowled over by your reviews of these two fine films. It was a superb job of comparison, and you brought out nuances and details that I had missed long ago. (Thank you for the photos, too – my favourite is the last one, of Hackman taking aim . . . finally!)

Not that I rely on the Oscars for my moviegoing, but I was thrilled that the first film did so well, deservedly. I remember the early Seventies as an exciting time for “going to the movies,” even for watching the Oscars! In that pre-cable/DVD era, people queued around the block (certainly here in New York) for a variety of films: ON HER MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE, PATTON, DISTANT THUNDER, BLAZING SADDLES, DAY FOR NIGHT, AMARCORD, ENTER THE DRAGON, MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS . . . sorry, getting carried away here! You get the point.

Thanks, Rod, for taking me back to that time! And also for your obvious love for film and the effort you put into your work, far superior to those of the “mainstream” critics! I’ll look at more of your work as time permits.

LikeLike

Thank you for this positive review of an often maligned film. I saw it again today. This review touched upon the positive items. My favorite part is Charnier’s reaction to sighting Doyle. I agree that the film gave closure to Popeye’s quest. I think that moving the scene to Marseille enabled Doyle to disconnect from his comfort zone and grow as a person.

LikeLike

I have to disagree with Sam Juliano’s statement that “THE FRENCH CONNECTION’s Oscar win in 1971 was one of AMPAS’ most infamous moments”. Actually, ” The French Connection” is a Best Picture winner that also happens to be a quality film. If one really wants to be outraged by the Academy’s sins, let’s remember that three American films that were in the top seven greatest films in the 2012 BFI / Sight & Sound poll didn’t win a Best Picture Oscar. Vertigo and The Searchers weren’t even nominated.

Correction to my previous post — make that four American films in the BFI / Sight & Sound Poll’s top seven that didn’t win the Academy award for best picture (Vertigo, Citizen Kane, 2001 and the Searchers). However a fifth American film, Sunrise, did win the best picture in 1927 (it comes in at #5 in the poll).

I know this horse has been beaten beyond a thousand deaths, but my point is that the AMPAS’ naming of “The French Connection” as the best picture of 1971 is hardly one of its more grievous sins. And I apologize to those who find polls odious.

LikeLike