Director/Coscreenwriter: Andrew Stanton

By Roderick Heath

I take the popular dismissal of John Carter a little bit personally. When I was young, I loved films based on Edgar Rice Burroughs novels—any version of Tarzan, of course, but also the lively battery of Burroughs-derived films made by British director Kevin Connor in the mid ’70s. I owe a considerable amount of the growth of my love for the fantastic genres to those movies, and therefore to Burroughs. Yet I’ve read a lot of commentaries blaming the relatively poor box-office performance of John Carter, the new Disney-produced, $250 million movie taken from Burroughs’ beloved, much-imitated Barsoom series, on its being adapted from esoteric material, as if a great bulk of what is popularly thought of as science fiction doesn’t derive specifically from Burroughs’ ideas, and as if his tales don’t offer a wealth of interest for the fantastic filmmaker and filmgoer. Of course, those ropy old flicks I loved didn’t cost such colossal sums of money, but attaching discussions of the decadence of modern Hollywood to its less successful products is, in a strange way, still playing Hollywood’s game, considering the way the industry and its pseudo-populist champions wield the successful ones, even the ones that are terrible, with bludgeoning contempt.

When Hollywood is starved for strong stories to tell, as it certainly is now, one way to get out of that slump is to dig back into the vast trove of great material provided by scifi, fantasy, and other genre writers over the past century, most of it largely ignored in favour of shallow appropriations and constant recycling. John Carter’s failure to connect is especially bitter, from this film viewer’s perspective, as blockbuster cinema has stooped to adapting board games and fun park rides rather than solidly conceived tales. John Carter is weighed down with a painfully bland and obfuscating title, one which hardly solves the presumed problem of esoteric material and betrays the real sensibility of pulp thrills and soaring space opera that the film itself communicates, in what is nonetheless one of the most purely enjoyable, rousing, and dashing examples of big-budget cinema I’ve seen lately, perhaps indeed the best since the last The Lord of the Rings film. It’s Avatar without the new-age ponderousness, Star Wars with more ideas and strangeness, Flash Gordon with a deeper hero. Although it lasts more than two hours, it moves with the rapidity of a serial from the 1930s.

Director Andrew Stanton does not defeat all of the familiar problems of modern blockbuster cinema, which resists that personal sense of the mythic that made, say, the early Star Wars, Indiana Jones and Superman movies so particular for their makers and audiences. The first half-hour of John Carter, whilst doing nothing especially wrong, does nonetheless wrestle with problems of exposition and locating the emotional gateway into the tale—vital elements of the fantastic drama that many modern franchise flicks treat increasingly like chores, tossing them away in rushed, voiceover-laden prologues. Star Taylor Kitsch, who made his name in the TV show Friday Night Lights, is a competent and likable but also frustratingly unspecific leading man, in a role that needs wit, gumption, and a real air of both grievous hurt and eccentric heroism.

But John Carter sports a screenplay cowritten by Stanton and novelist Michael Chabon, who has long burrowed into the serious underside of the pulp pantheon. They infuse John Carter, as it evolves along with the world it portrays, with a depth of feeling and crowded panoply of detail that soon takes on a feverishly enjoyable aura. The script expands on and conflates Burroughs’ original tales in numerous ways, particularly in the wraparound narrative that frames A Princess of Mars, the first of Burroughs’ novels set on the red planet its inhabitants call Barsoom. The film conflates the young first-person narrator whose uncle John Carter is in the book with Burroughs himself, and he becomes party not merely to Carter’s supposedly posthumous tale, but also to a clever plot that pays off in the very conclusion. Carter’s experiences gold prospecting and his attempts to survive frontier dangers are, likewise, recast to reflect the more exotic, off-world scenes he will encounter as he shifts from ethnic conflict here on Earth to those on Barsoom.

Stanton, who, of course, has come to features after several hugely successful animated films and moves immediately in the footsteps of Brad Bird’s success with Mission: Impossible 4 (2010), retains an animator’s necessary sense of pace and humour: indeed, an early series of gags that Stanton pulls, as Carter keeps trying to escape the custody of army officer Powell (Bryan Cranston), would be funnier if rendered in the quicksilver technique of animation rather than in bruising three dimensions. Stanton does, however, display a remarkably fleet-footed capacity to keep his story and visuals in motion, with a narrative that threatens at times to be top-heavy, and after that initial uncertainty, Stanton nimbly keeps pace with our hero’s efforts to keep an even keel as he’s presented with multifarious strangeness.

As Burroughs learns through the journal Carter leaves him along with his whole, vast estate, Carter survived the Civil War where, serving for the Confederates, he emerged as a hero, only to find his wife and child had been killed in raids. To make his fortune and leave behind the humanity he now detests, he goes prospecting for gold in Arizona, where he is picked up by the bullying Powell, who wants to force him to help fight against the Apaches. John resists and escapes. When Powell and his men give chase, they instead earn the wrath of an Apache band, and in the ensuing fight, Powell is wounded. John drags him to the cave, known as the Spider cave because of a motif carved within, where he’s been finding gold. As John ventures into the recess, a mysterious being beams into the cavern, and John shoots him. An amulet about the dead man’s neck is actually the control device for the wormhole that opens and sends John, or rather a kind of facsimile of John, across space to the Martian hinterland.

John finds himself in the midst of a knotty civil war that’s been engulfing Barsoom for centuries, between the kingdoms of reddish-skinned humans, Helium and Zodanga, and the green-skinned, horn-faced, four-armed Tharks, amongst whom John first finds himself captive. The Tharks, formerly a sophisticated civilisation, are now violent and degenerate. John soon discovers he has great strength and a talent for leaping incredible distances because of Mars’ low gravity, traits that endear him to the Thark king Tars Tarkas (voice of Willem Dafoe). Tars, more emotional and open-minded than the other Tharks, knows that the much-victimised Sola (Samantha Morton), to whom John is mockingly given as a baby to raise, is actually his daughter, unusual knowledge when most Tharks are adopted indiscriminately after hatching from eggs.

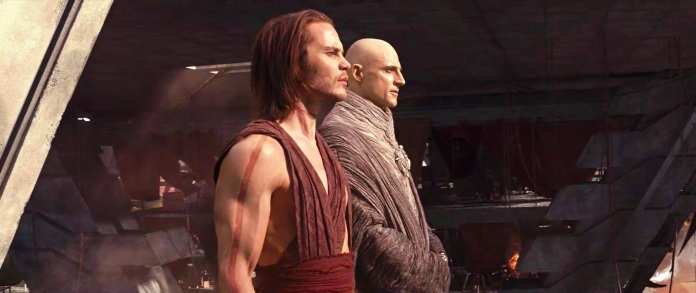

When circumstances force Tars to take John and Sola’s side, he is toppled by nasty warrior Tal Hajus (Thomas Haden Church). Meanwhile, Helium is at risk of finally losing to Zodanga because its king, Sab Than (Dominic West), possesses an incredible new weapon that fires the elusive and powerful “ninth ray” given to him by a race called the Therns, one of whom John killed in the cave. The Therns pose as immortal and priestly, but they actually control fantastic technology, and they’re really stage-managing a victory for Zodanga which will lead to the final deterioration of Barsoom, an act of entropy which the Therns feed off. For a cruelly exact final victory, the lead Thern, Matai Shang (Mark Strong), instructs Sab to marry the princess Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins), scientist daughter of Helium’s king Tardos Mors (Ciarán Hinds), and then kill her, an act that will both cement his hegemony and, with Dejah’s attempts to master the ninth ray coming too close for the Therns’ comfort, eliminating her dangerous intelligence. When Dejah tries to escape Sab, his flying ship catches hers above the Thark city.

It’s in the action sequence that follows that John Carter truly snaps into full working order. John, enraged to see a human woman being terrorised, springs into action and devastates Sab’s warriors and ships with his unbound earthly talents like Errol Flynn slipped free of earthbound laws, ripping loose in sheer spectacle with dashes of physical comedy and surrealist absurdity, as John’s sudden superhuman prowess swings between awesome competence and jarring clumsiness, and Sab nettles under Shang’s restraining influence. Again, Stanton’s background in animation, where the laws of physics can be bent easily, comes out here to more perfect effect, and the film retains a visual fluidity that makes sense of crowded scenes of action. Likewise Stanton, in a fashion familiar for animators, has a gift for finding the appealing quality in seemingly grotesque things, like the wailing, slimy Thark babies who cuddle up to John lovingly in their lair, and a super-fast creature that looks like a lump of silly putty with legs, placed menacingly on guard outside the Thark nursery, but which proves to be essentially a weird kind of dog. When John defends it from being beaten by the Tharks, it becomes his inseparable companion.

Stanton and his production team seem to have carefully parsed old comics, book covers, and illustrations for the conceptual universe, combining elements of steampunk and retro-futurist wonder with the edge of oriental exoticism so common in that old artwork—Mameluke guns, neo-Trojan armour, and Scheherazade dresses. Zadonga, a mobile city that moves along on gigantic crawling mechanics, is an almost casually employed wonder of design and execution teeming with detail, and so is the great cathedral of Helium where gigantic rotating lens and arcane religious ritual converge. But perhaps Stanton’s most impressive sequence of visual control comes when Matai Shang, having taken John prisoner, leads him through the city’s crowds and explains his plans with casual arrogance, whilst changing forms, forcing John and the audience to move with the flow of convenient guises.

Keeping a plot that is complicated less by intricacies of action than by an array of competing sides is difficult, but John Carter is never less than entirely coherent, even in the multilayered battle that wraps it up, something like genius compared with the dizzying incomprehensibility of the Transformers films, where even simple brawls are impossible to follow. The greatest fantasy-adventure films tend to have an elegiac sensibility, a sense of space that allows time to breathe in the landscapes and drama with hues of awe and tragedy, but John Carter largely moves too fast for that. Such films also usually tend to have a breath of the otherworldly, the exotic, and the erotic, for example, the gleefully perverse scene in The Thief of Baghdad (1940) where the narrative takes time out to portray the seedy old sultan stabbed to death by the alluring facsimile of id-filtered femininity provided by the evil sorcerer. The erotic only gets a look in here in the alluring fleshiness of Dejah’s apparel, and even that’s pushing it for a Disney film, but there’s an underpinning of emotional seriousness to the tale that means that it never descends into shallow pictorial splendour. This quality is especially embodied by Collins’ breathy earnestness as Dejah in a strong performance that elegantly and effortlessly bestrides the schism of luscious physicality and intelligent conscientiousness so well she subverts any notion of a disparity. Her radiant humanity contrasts the coldly calculating Matai Shang, well-played by Strong, a figure whose affectation of incorporeal imperative and godlike power hides a cynical program of profit by exploitation and degradation, an idea with interesting resonances.

Stanton admirably tries to wield a certain amount of darkness of the kind that Disney have usually tried to keep out of their movies since the bad old days of The Black Hole (1979) and Dragonslayer (1982), from the sorry spectacle of Sola being branded—she has so many brand marks there’s no room left on her body—for her perceived transgressions, to the marks of visceral tragedy John carries upon his soul. Whilst the pitch of the depressed and disillusioned war veteran has become a tired motif in action-adventure movies, like the pseudo-historical variation on this theme, The Last Samurai (2003), Stanton wrings it until it pays off in a legitimately great sequence in which John, refusing to be chased further by an army of evil Tharks called up by Shang, and to give Dejah and Sola a chance to get away, launches himself into the alien horde and hacks it to pieces with astounding fury. Stanton presents a dialectic montage, cutting between the action and John’s memory of coming home and finding his house destroyed and his wife’s corpse, and then burying her; Stanton aims here for the furthermost reaches of emotive grandeur, coalescing old trauma, new love, and innate heroism into a singular whirlwind of expressive carnage.

One distinct pleasure of John Carter is indeed that it looks and sounds like all that money finished up on screen: the film’s special effects have a rich, beautiful intricacy that suggest that CGI-based cinema might only now be starting to come into its own, particularly wondrous when John, escaping Shang’s clutches, flees in one of the Zadonga flying machines that look like sculptures of large insects fashioned out of Victoriana crystal and brass, avoiding the city’s colossal motivators. The fact that the Barsoom tales have been so endlessly filched by moviemakers over the years, including Avatar, Star Wars, and Flash Gordon, and the fact that the film sticks firmly to some familiar templates—the scenes where hero John and Dejah wander in the desert bickering resemble the dreaded Prince of Persia (2009), for instance—do mean that to a large extent it can never feel entirely fresh. But John Carter outdoes the many films it resembles simply by doing such things better and by keeping its feet planted firmly in the legitimate quality of its source material.

Burroughs’ stories, like most prototypes, were joyous in having few set rules for how they should proceed; thus, they could be both romantic adventures and speculative fiction all at once, and something of their fulminating strangeness makes it into the movie, with its breathless procession of alien customs and reproduction habits and intricate religious sensibility. Just as The Land that Time Forgot and its 1974 film version offers up an old canard—a lost island populated with dinosaurs—but adds a notional interest in evolution and presented a microcosmic version of it that proves to have a strange, deistic motivation behind it, so, too, is there substance under all John Carter’s freewheeling invention. There’s an environmental message, most obviously, as the wicked Zardongans consume endlessly and contribute to their planet’s decay, but also an engaging amount of space for probing the nature of emotion in species that do not reproduce like humans, as in the Tharks, and a note of poetically opposite senses of wonder for John and Dejah, whose different kinds of ships sail different kinds of oceans, both equally strange and impossible for them to imagine. John trails faintly religious associations, as a messiah with the initials JC prone to resurrections and stepping in and out his corporeal form, but his enemies are false deists who visit people and guide them on to a destiny which is designed to be self-destructive to suit the Therns’ needs.

And perhaps that’s the real reason why nobody knew what to do with John Carter: it doesn’t carefully and neatly beat one essential theme into the ground like most of these colossal blockbusters, but serves as a big, tottering, server platter for a truly complex universe. It helps that Stanton avoids belabouring things that other directors might stretch out, with an occasional anticlimactic flourish, as when John challenges Tal Hajus for the kingship of the Tharks: Tal Hajus hurls himself down from on high, John leaps up, and in the next moment Tal’s head is rolling away on the sand. Similarly near-satirical is a subsequent sequence where the Tharks make a grand charge to the rescue of Dejah, only to arrive in Zadonga and find the wedding is taking place in Helium, and Tars Tarkas can only express frustration by slapping John in the back of the head. Later, when the Tharks have to do something they fear and loathe—trying to fly—the inevitable last-minute arrival sees Tars Tarkus crash-land through the cathedral wall and groan his pleasure that’s over with.

But the film’s set-piece action scenes are doozies, like the aforementioned flying chase, and John, in space opera’s compulsory arena battle, taking on colossal blind white apes, swinging huge chunks of stone on the end of chain to pulverise them, and Sola, finally angered to breaking point, tossing her constant foe Sarkoja (Polly Walker) into the arena for the fleeting pleasure of seeing her stomped. The climax is a wild melee as both John and Sab are targeted for assassination by Matai in the midst of a grand battle, and John tries to stop the Thern villain from escaping. Even after the story seems to be over, and John marries and beds Dejah, Matai’s traps ensnare him and exile him back to Earth, which seems now a cold and dreary exile for which his only answer is an intricately woven plan that involves his young nephew. John Carter, or John Carter of Mars as finally and properly amended, is one of the most satisfying rides I’ve had in a movie theatre in recent years. I do hope more of you go to see it, not because Disney needs the money, but because of a selfish personal motive: I want to see more movies like this one.

I’m planning on seeing it as a a Burroughs completist, and perhaps now in anticipation. I preferred the Pellucidar series myself, and some of his disconnected novels and novelettes, but John Carter stories always had grandeur more than the others, it’s true. I mentioned to a couple of people recently the influence of Roy Krenkel’s work on much of the recent fantasy films, more so even than Frazetta, but especially for this film, from what I’ve seen, which interests me a lot. Nice review, whets the appetite.

LikeLike

Van the Man: At The Earth’s Core, baby. Peter Cushing, Troy – er, Doug McClure, and Caroline Munro – the Holy Trinity of Pulp Cinema! Personally I’d like to see more of a Boris Vallejo influence out there, but I’m kinky.

LikeLike

Oh, yeah, McClure was a great Burroughs interpreter-by-default. – don’t forget The Land That Time Forgot!

LikeLike

Yes, as mentioned much above.

LikeLike

Nice, well-considered write-up. I’m glad I’m not the only one who liked JC. Even my nine-year-old was unimpressed. I rather enjoyed the sheer ‘boys’ own tales’ quality.

If David Fincher can come back after the awful Alien 3, Andy Stanton should hopefully get over the crit and make more of this kind of thing.

LikeLike

Well said, Rod! I think that this film probably doomed from the get-go. It seemed like so many people were gunning for it judging by the almost gleeful prognostications of its demise and then the “i told ya so” post-mortems when it failed to dominate the box office.

However, as you point out, there is a good film there, desperate to connect with a mass audience turned off by confused marketing. One can hope that it will find a second life on home video.

LikeLike

Tony: wow, your kid didn’t like it? That depresses me. Of course the good old Boy’s Own flavour isn’t every boy’s own cup of tea. I too hope Stanton can come back – he’s got the goods. Strangely, although I don’t like Fincher much, I always found his sense of style to be Alien 3‘s main saving grace after the artistic abbatoir that was its development process – and I think others in Hollywood realised that too. But Hollywood’s rules almost always follow the money. For instance, I just watched the Conan The Barbarian remake, a dreadful film by a dreadful director that lost a ton of cash, but only because said dreadful director had made a lot of it with cheap, recycled trash. That’s the sort of film where it’s approaching a pleasure to see it bellyflop.

JD: Well, we all know what they say about how everyone has an opinion and what those are like. I suppose one point that should be made is that this film has made a huge amount of money, far more than most movies can dream of; it’s simply that it cost so damn much. Perhaps this represents a Cleopatra-like moment in Neo Hollywood, where the fact that something can be a hit and yet still a painful flop signals something has to change. But, you know, The Avengers will probably make squillions, and things will be back to normal. I suspect rather this has highlighted just how bad Hollywood’s marketing minions are becoming at backing things that don’t already have most of their work done for them: they’re too used to having the hype of big novel successes or pre-existing franchises.

LikeLike

A truly outstanding review, and I particularly appreciated the discussion of cinematic elements as well as exploration of the story’s themes. For too many people, ERB and his stories are just ripping yarns with nothing going for them beyond being fun, entertaining diversions, but there truly is some depth and richness inherent in the stories which was partially captured in the film.

The dismissal of John Carter is just another example of follow-the-leader. Critics only tend to like and dislike the films they’re told to like, either by the critics they idolize, or the studios themselves poisoning/sweetening the well with press-packs. And what’s telling is that many reviews are uncannily similar to the reviews I’ve read of Star Wars from 1977.

It’s one of those rare cases where I will stick my neck out and say people didn’t get it. Normally I loathe that perspective as being simplistic and condescending, but to me the qualities of John Carter were so evident that I simply cannot fathom so many being so openly contemptuous.

LikeLike

“Stanton and his production team seem to have carefully parsed old comics, book covers, and illustrations for the conceptual universe, combining elements of steampunk and retro-futurist wonder with the edge of oriental exoticism so common in that old artwork—Mameluke guns, neo-Trojan armour, and Scheherazade dresses. Zadonga, a mobile city that moves along on gigantic crawling mechanics, is an almost casually employed wonder of design and execution teeming with detail, and so is the great cathedral of Helium where gigantic rotating lens and arcane religious ritual converge..”

An utterly magnificent insight in a wholly spectacular effort. And I am delighted to know that you are going to the mat for a film I like very much as well. I originally assessed with a 3.5 of 5 rating, but now it’s a solid 4 of 5. I was originally perplexed then downright angry that the film received divided reviews, but just like Darren Aronofsky’s THE FOUNTAIN from 2006 that practically split the critics down the middle, I think it’s a film that is largely misunderstood and is destined to gain in reputation. The script was better than I thought it could be, the visuals (though some obviously indepted to other films) were largely captivating, the performances solid, and a nice score by Michael Giacchino to boot. I’ve been furthering my research on Edgar Rice Burroughs, an author I had a crush on many decades ago, while reading the Tarzan series. I agree the special effects were ordinary as far as these type of films go, but I was far more interested in the script and characters anyway. And the Mars seting was ever-intriguing. Above all perhaps I though the ‘tone’ was precisely right. My kids liked it a lot, and my wife thought the central actor was “easy on the eyes.”

This masterful defense and validation of this grossly underrated film deserves a permanent place in the JOHN CARTER literature. It would do Burroughs proud.

LikeLike

Hi Sam: yes, it’s good to have a friend on this – but I hardly feel lonely. Generally the grass-roots reaction for this film as I’ve encountered it, from hardcore Burroughs fans to lovers of the cinefantastique in general, has been overwhelmingly positive, even if the snark from the critical establishment (which as I’ve hinted here is, I think, based more in feeling safe to go in for the kill with a lone blockbuster separated from the herd and ailing rather than by actual attention to the film at hand) has been hard to cut through. If the film’s budget allowed it to settle for cult hit status this would be an overwhelming triumph. I didn’t say the special effects were ordinary; I praised the special effects as enriched and superior! Yeesh. But yes, characters and script, both engaging and rounded and well-fulfilled by the scale of filmmaking. Speaking of Giacchino’s score, I was surprised to see the music was by him, as it seemed to have little of the rousing personality of his great score for Star Trek. Perhaps it’ll strike me more next viewing. Anyway, the faults I found with this were marked but minor – 4 1/2 stars from me, if I gave out stars, which thankfully I don’t have to, and a sure place on the end of the year list, which indeed has already got a few likely candidates. I predict – with my usual Criswellian accuracy no doubt – that this will have a long, long video life indeed, perhaps much like Big Trouble In Little China, The Neverending Story, and some of the other much-beloved cult flicks of my own youth that were, surprised as we all were later to find, actually big flops on release.

BTW, This Island Rod is alive again.

LikeLike

Hi Al. This film was declared a failure well before its release, so there was always an element of self-fulfilling prophecy to this sort of thing, and I rather feel that was the real enemy in this equation. I can’t put its failure down to people not getting it; certainly a lot of them haven’t, indeed, but others have, and you could say exactly the same thing about Twilight and Harry Potter, which made squillions from the number who did get it. It’s rather been a question of getting the word out. The kind of care in whetting the audience’s appetite that Hollywood has supposedly become so good at was simply lacking with this film. Critics – some, perhaps most, but not all, critics – have been reluctant to help out, but really they can’t influence the fate of filmmaking on this scale much anymore, if they ever could.

Certainly the follow-the-leader thing as you put it has a lot of truth to it. What does intrigue me is the fascinating disconnect the film has revealed about the corporate cinema culture that has spawned it. On one side, funnelling such huge sums of money and commitment at the production end, seemingly a vote of utmost confidence, and then offering up an incompetent and half-hearted marketing scheme, and vague admissions that they never really had much hope for it, on the other. Perhaps if it wasn’t Disney, with such huge and reliable revenue streams that it can afford such a thing; if it was Lionsgate with Twilight or New Line with The Lord of the Rings, for whom those were vitally important even make-or-break ventures, they’d’ve gotten behind their product, or found somebody who could. And I can well imagine the similarities with the old Star Wars reviews. The reaction that it and Close Encounters of the Third Kind got from the old critical guard was astoundingly negative. Of course, the situations are reversed to a large extent now: back then there was a culture of easy contempt for broad-audience movies in the fantastic genres and those movies looked like freakish ogres, whereas now those things are commonplace, and inspire a different kind of contempt for that commonness.

LikeLike

Very surprised by how much I enjoyed this movie. Excellent review!

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it, Kristen!

LikeLike

When I was watching this movie last Saturday, I kept sitting there in the audience bracing myself for whatever it was about the movie that was going to render it bad. Because, well, whenever an expensive Hollywood production flops and gets horrid reviews, you can see spot the reasons why: Heaven’s Gate, Waterworld and Oliver Stone’s Alexander are all like that. They have incredible individual sequences but making for such overall boring, wasteful epics.

And yet the financial failure of John Carter is, as was the case with Hugo, quite obviously due to the bad marketing and vague title. I mean, c’mon: this movie is so entertaining! It’s so much fun! It’s a crowd pleaser! There is absolutely NO good reason why it should be flopping the way it is. It’s clever, imaginative and exciting. By the time of the giant white apes sequence, I was like, “Yeah, this movie’s on a roll.”

Disney may lose truckloads of money, and it may have even lost its faith in Andrew Stanton as a bankable filmmaker, but I don’t care. The cult followings will rescue it over time. And I demand a sequel, too.

LikeLike

If you ever bad-mouth Heaven’s Gate as boring and wasteful in company with Waterworld and Alexander in my presence again, Adam, you and I are going to have a serious disagreement.

As for the rest, no disagreement.

LikeLike

Rod: You should write about Heaven’s Gate. That might compel me to sit through it again. When it comes to that movie I basically agree with Matt Zoller Seitz’s opinion: I appreciate the idea of it, but the fact of it is rather less enjoyable.

I mean, I love Cimino — The Deer Hunter and Year of the Dragon are both pretty fucking gorgeous — but during Heaven’s Gate I remember basically thinking, “There are some nice shots here, but I have no idea what’s going on.” Unlike Stanton’s movie, which never lost me — ever.

LikeLike

I am planning to write about it in the near future, circumstances permitting. It’s a film I love and think is far better film than The Deer Hunter. Admittedly it is a film that took me more than one viewing to appreciate. Out of curiosity, which cut did you see? I can’t see anything in the remotest bit confusing about the director’s cut.

LikeLike

If I remember correctly, it was the director’s cut on the current MGM DVD. I wasn’t so much “confused” by the film, more like having to constantly remind myself what was setting the plot into motion. Now, when it was over, I do remember going on Facebook and making some pretentious comments like, “Woo-hoo! I made it through Heaven’s Gate, and it’s awesome!” but in retrospect I think I was just trying to thumb my nose at the movie’s detractors for the sheer hell of it.

Not that I reject any defenses of Heaven’s Gate — I’m very intrigued to read yours whenever it gets published — but I would never have been able to mount a case of my own in the movie’s favor because I’m pretty sure I was kidding myself into liking it more than I actually did. These, mind you, were the ravings of me as a freshman in college (still very inexperienced as a young blogger), so I would never pull that kind of shit today. Were I to review Heaven’s Gate at the time, I would have had to be willing to sit through it immediately after watching it, which I confess I would not have had the guts to do. The movie hadn’t impressed me as much as I liked to think it had.

John Carter, though? I’d watch it again in a heartbeat — because I know for a fact what I loved about it and could explain what it is that I loved about it, as you’ve so eloquently done here with your piece.

LikeLike

Just so the full spectrum of opinions are represented here– I adore “Heaven’s Gate”, and consider it one of the best pieces of American cinema from the past however-many years, whether or not it was a success or derailed the New Hollywood movement. I also thought “John Carter” was an incoherent, unremarkable piece of genre-overkill embarassment that makes the campy “Flash Gordon” flick from the 80’s look like a great work of art (at least that film had legitimately good acting– Flash himself may be a big rack of know-nothing beefcake, but Blessed, Dalton and especially Von Sydow are gold). It’s interesting to see the two movies placed in the same register just by the fact of their high budgets and financial failure.

I see the reception Cimino’s film got as mostly due to the wave of the New Hollywood movement finally turning back and receding, as well as audiences growing chillier to the big David Lean style epics year after year (to say nothing of how bleak and hostile it is to the mythos of the American frontier). It was a great film that was in the wrong place at the wrong time. As for “John Carter”– yes, it was marketed wrong (thanks to Stanton, who had control over that department) and it had to contend with the fact that the Burroughs stories have been picked and borrowed from by other filmmakers for decades. But at the end of the day, if it really was all that good a movie, it would’ve found an audience on its own.

LikeLike

Bob, while I’ll just have to agree to disagree on Flash Gordon’s relation to John Carter, I must point out that the latter film HAS found an audience: a fairly significant one. It was the biggest opening-day box office in Russian history, second-biggest opening day for a Disney film in China, and has been one of the top movies on the international scene since its release. True, it may not make back its budget, but it’s also hardly on a par with the likes of Cutthroat Island or Sahara. Indeed, when one takes the US out of the equation, John Carter’s actually been doing pretty well.

LikeLike

Al, I’ve been in this same position, trying to read the tea-leaves of international audiences to find the bright side in an expensive blockbuster that fails to make good. I spent a good long time hoping that “The Golden Compass” would make enough money around the world that New Line would eventually greenlight the other books in the “His Dark Materials” trilogy, but it never happened. But that was a case of a movie that was sabotaged by their studio with recuts, editing much of the heart and soul out of the Phillip Pullman story (to say nothing of the ending). With “John Carter”, the studio was if anything too permissive of the filmmaker, so it’s a different situation from a lot of other flops in many regards.

There are cases where you can argue that a so-called bomb redeems itself with the international markets (“Waterworld”, which I’ve always kinda liked, more than earned its money back factoring the overseas audiences). And in the end, the more important issue to me is whether or not “John Carter” is a good film, which in my opinion it isn’t. The box-office issue is really a matter of disecting what kind of a movie it is, versus what it’s turning into. People have been saying that, in time, it’ll gain a cult following on DVD, comparing it to stuff like “Dark City”. But there’s a big difference between the mainstream stuff that flounders into niche audiences, and the oddball genre experiments that were never going to be big hits to begin with.

LikeLike

Cool – commenters arguing amongst themselves! This place is becoming positively salon-esque.

Whilst obviously I’ve come out aleady in the camp of both John Carter and Heaven’s Gate, I will say that both are united at this moment by their being movies worthy of forthright discussion and respectful consideration, and that personal right to decide whether a film is good or not as Bob says, and in that regard then the ideal for every movie is an uninspiring breaking-even. But one is instead frustratingly forced to deal with such movies in light of poor box office, being that absolute value which Hollywood has now imposed on the rest of the public, and is supposed to be entirely and purely the realm of crap – Battlefield Earth sized crap.

In the case of Heaven’s Gate, it’s important to note that I feel it can hardly be called a flop in the same way that JC can; whereas JC has been released with a big studio’s however half-hearted hype behind it, Heaven’s Gate suffered because there was a definite and proactive attempt to sabotage its chances for success. As well as the film’s spiky take on the west, Heaven’s Gate‘s fate seems to purely reflect a determination to present a propaganda victory over studio reliance on auteurism: the blame was heaped, as with Stanton and JC, on the director’s “arrogance” rather than the supposedly responsible suits who control the pursestrings. United Artists was bankrupted by a series of big failures, and the expenses of Heaven’s Gate, granted, which they felt could not be recouped, and the studio had to be sold. So Heaven’s Gate was thrown away by the new management that needed to clear the books; in fact, a little like a scenario out of The Producers, if Heaven’s Gate had been given a chance to be a success, it might have left UA in a worse position than the MGM purchase did. What little money they tried to wring from the film they decided to make by hacking it down to the point where it was barely comprehensible, and waltzing it through theaters in a short release geared to action fans who were, unsurprisingly, bewildered. Heaven’s Gate is one the singular examples not merely of a movie not making money, but of the way the narrative of the big flop is carefully propagated as a self-interested mythology by Hollywood.

LikeLike

Excellent review and excellent discussion that follows. I won’t add anything to the interesting analyses about the film’s marketing and box office (except to take note of the interesting idea that this is a bit of a propaganda war for the “suits” against the “creatives”).

On the film itself, I felt there was one flaw that you didn’t mention and that was the repetitious nature of the dialogue between John Carter and Dejah. Right from the start, it was that tired refrain of selfish hero versus idealistic babe, which I could live with. But it seemed like they kept having the same conversation over and over. It stopped the movie dead at least three different times, times which could have been spent showing John Charter enriching his own knowledge and appreciation of this world (when he gets sent back to earth, the audience feels disappointed because we have left that fantastic world and you sort of sympathize with John Carter by proxy but you don’t directly feel it coming from the character at all) or perhaps hinting a bit more at how the Therns deirve their power (though I felt the subtle explanation of the backstory was the perfect amount, just enough to explain but left enough back to keep us wanting more), anything than another “what is in your heart!” “You lied to me!” back and forth.

Otherwise, though, a thoroughly enjoyable movie. I cheered twice, when the dog takes out that Thark on his mount and when John Carter tells the Thern that he already killed one of his kind with a gun back on earth. Stirring moment!

Oh yes and the dog thing ruled.

LikeLike

walkerp; I do know what you mean, those exchanges are repetitive and it is part of what I meant when I took a shot at the “bickering in the desert”, but really I let it pass for two reasons: Collins acts them so earnestly that they became significant aspects of her characterisation, and the conversations are just words covering the couple’s growing attraction over divides of not only space but sensibility and moral world-view, and especially in the way Dejah finally, tiredly admits that she’s been lying to John and that she could read the symbols on the amulet, where earnestness gives way to honesty and ironically that affects John more. But yeah, those cheer-along bits you mention are great.

LikeLike

RH, I totally agree with you on JOHN CARTER right down the line. As someone who was an employee at Disney back during the “bad” days (I started the week before BLACK HOLE went into production and left while the M&E track for TRON was being mixed), it’s great to see something as layered as this in a computer-generated movie. There even seemed to be a little borrowing from the tits-and-sand 1940s epics of Maria Montez and Turhan Bey in some sequences. And the bad press it has gotten only underscores to me the herd mentality of the generally-clueless journo-crits. What a pleasure to read!

LikeLike

DB, that’s damn interesting about your time with the company in its inglory days; I just recently I revisited Dragonslayer from that time (it’s written up over on This Island Rod) and I always found it interesting how Disney seemed to fumble and stutter when it came to trying to appeal to the teen demographic Lucas and Spielberg so aptly captured, but the results of their efforts were still interesting and eccentric. And that’s also a very apt comparison with those old movies: whether intended or not, all of these things are drawn from the same wells. I actually came home and watched the Powell-Pressburger The Thief of Baghdad again not long after seeing John Carter for precisely that reason.

LikeLike

Before going to the employee screening of DRAGONSLAYER (which I didn’t work on), a buddy told me that the minute I see the dragon crawling toward the camera, I’d stop being depressed over the retirement of Ray Harryhausen. I thought it was really well done, although the denouement’s bright optimism of “Down with sorcery; hooray for a future with a religion which will bring upon us a few centuries of witch burnings and inquisitions” was an early sign of the future cultural shift under the (then) newly elected President Reagan.

LikeLike

DB, yeah, the dragon’s damn well done. I particularly like its crawling scenes – there’s something strikingly realistic about the motion, which made me think when I first watched it, many moons ago, that they’d taken an iguana or something and pasted appendages on it. But I have to take issue with the way you characterise the finale: my distinct impression, which may or may not have been what Disney thought they were doing, was of the ironic spectacle of the king and the religious flock each claiming a victory, and a social preeminence, that they had no real right to, with nothing at all to suggest that either is preferable, whilst the optimism is about our young heroes going on their way to find what the world holds for them.

LikeLike

Rod – Obviously, I’m late to the game, but it was a blast to see this with Shane, grandson Jacob, and a respectable-sized audience at a vintage theatre – it seemed like the right setting for a film based on material from a different time. Oh and just to put a point on it, the audience applauded at the end of the film – so much for its “failure” in the domestic market. The write-down was strictly an accounting thing.

I agree right down the line with your assessments of the film, except that I felt that the underdeveloped wit extended beyond Taylor Kitsch, though perhaps he set the tone. The scene where he’s trying to learn to walk on Mars should have had me rolling in the aisles, pratfall lover that I am, but it, um, never got off the ground. Still, it seemed that Stanton was interested in the more serious underlying story. The drama was superb, and Collins was as great as Sandahl Bergman was in Conan the Barbarian. This film was evocative of that great fantasy tale, including the great scenes where John Carter remembers coming upon his burnt homestead. The pacing of those memories couldn’t have been better or more expertly edited. I loved, loved, loved the ending, too. Thanks for putting me onto a film I have wanted to see ever since reading this review.

LikeLike

Hi Mare. It sounds like your problem with that scene might be a little like my problem with the earlier trying-to-escape-from-Powell’s office bit; Stanton hasn’t quite attuned himself to how slapstick humour works differently with solid objects than with pixels. But yes, Stanton really did take his story seriously, hallelujah, and I love your comparison of Collins with Bergman. And the ending: yes. That final image of John lying down on his bier to “die” is indeed stuck vividly in my memory.

LikeLike

Beautifully argued piece as ever, Rod.

Finally gave this a spin last night. I don’t know, man. It played exactly like I thought it would play since I saw the first trailer… specifically, like the last Tron flick. Disney sets out again with the best will in the world to make a thoughtful science fiction film with smashing set-pieces and the resulting movie – beset with hollow talk of ‘great change a-coming’ – feels as airless as the peak of Olympus Mons.

Don’t get me wrong, the airship rescue and arena bout boast a pure pulp power that’s impossible to resist, but the surrounding politicking and high-plains-drifting represented (excuse me) a cinematic desert for me. it didn’t deserve to go belly-up quite so dramatically, but neither is it a secret masterpiece. I’d be hesitant as well to ascribe it ‘cult classic in waiting’ status like you and Bob, as it’s just too competently, carefully made, too *square* to appeal to the same people who wear out their copies of Big Trouble, Little Shop, Sucker Punch et al – too few jagged edges.

BUT.

Today, I can’t seem to get it out of my head.

The thought of Carter’s ten year exile, and yes, that final surrender of earthly drudgery to high adventure on the death bed of a compromised soldier, a man who’s risen as high in this world as – well, I’m getting wound up right now, as you see!

My thoughts keep turning to what that return would look like, how this rich cast of characters would respond to him after his long and mysterious absence. For all my grousing, I’m curious about the further lives of these people in this setting. I wonder what heights a sequel would reach having undergone the drudgery of bedding in the world for the audience in this film.

I suppose the best I can do on that score now is re-read The Gods of Mars and extrapolate. Ah well.

LikeLike

Excellent review. It is a pity that there probably will not be a sequel, since the hard work of introducing the world of Mars has been accomplished. Stanton clearly had trouble directing comedy with humans rather than animated characters, which is why the scenes with the most humor were those with the Tharks’ version of a dog. However, the sweep of the movie was impressive, and it was fun, which is really the point for this kind of movie. Carter’s return after an absence of ten years would be an intriguing starting point for a sequel, since there presumably would have been changes.

LikeLike

Andrew: yeah, the dog almost stole the show at points. Indeed, the sequel could be slipped into with the greatest of ease. I was fascinated to find that the actual first novel, A Princess of Mars, ends on a cliffhanger, with John living in uncertainty as to whether or not Dejah and others had suffocated. Could you imagine if this film had ended like that? It would dwarf The Golden Compass as the great example of the under-performing blockbuster with unresolved ending as existential crisis.

LikeLike