.

Director/Coscreenwriter: Gary Ross

By Roderick Heath

Suzanne Collins’ hugely successful novel The Hunger Games and its follow-ups about Katniss Everdeen, teenage huntress at war with a futuristic dystopia, were obviously written with the hope they would become major motion pictures. With their driving plots, experiential style, and unremitting forward-march pacing, the series cunningly condensed a host of popular hooks and iconographic-ready ideas, and crafts them into an attractive package for our era. Chief amongst these is Katniss, the tough, skilful, emotionally discursive heroine, of a breed far more common today than they used to be but still sufficiently unique to earn plentiful encomiums in critical commentary. She is coupled with a plot that, like similar recent cult hits, including the Japanese novel Battle Royale and its 2000 film version by Kinji Fukasaku, the Australian novel and film Tomorrow, When the War Began (2010), and even the Triwizard Tournament of the Harry Potter tales, evokes the darker sides of modern teenage existence. The joyless competitiveness forced on it by adult social expectations and the cruelty asserted within itself, as well its very familiar fantasies and hopes, are placed in heightened situations that sharpen the metaphors to melodramatic points.

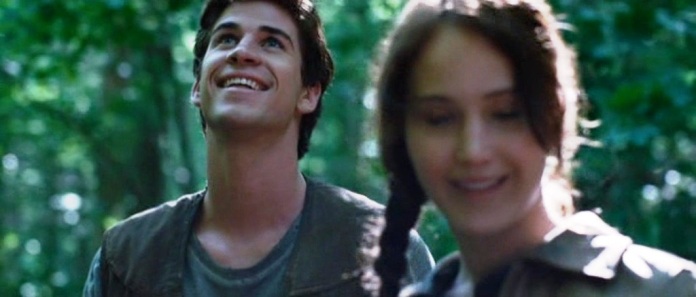

If I’m sounding a little jaded about Collins’ creation, which I enjoyed reading, it’s because the more I thought about The Hunger Games, the less and less satisfied I was. It’s a novel that carefully sets up a situation that is, by definition, a zone of moral nullification, and yet contrives to have our heroine emerge smelling like a rose without ever having to make a genuinely hard choice, in a tale that counts finally as neither effectively elemental nor symbolically rich, but rather as efficiently marketable: In fairness, the second two novels do amass genuine complexity, and admittedly, there’s only so far one can go in engaging with moral ambiguity and depth in a book aimed squarely for a young adult readership. But Katniss remains such a clean-cut moral avatar for her audience, in high contrast to a hellish scenario, that its starts to feel somehow dishonest. There are many things that seem right about Gary Ross’s film adaptation, especially most of the cast. Jennifer Lawrence, so strong in Winter’s Bone (2010) and so dispensable in X-Men: First Class (2011), returns to form as Katniss, the prematurely hardened lass who’s become an excellent archer thanks to years of having to provide for her younger sister Prim (Willow Shields) and shell-shocked mother (Paula Malcomson) following her father’s death in a mine explosion. Katniss is a citizen of the poor, retrograde District 12, a mining commune that forms one of the dozen oppressed fiefdoms of Panem, a future state that has risen from the ashes of a North America wrecked by various, fleetingly described calamities. Katniss enjoys hunting in the woods outside the boundaries of the district with her hunky guy-pal Gale (Liam Hemsworth), but fate, and the peculiarly vicious futuristic version of the social contract, has nasty things in store for Katniss.

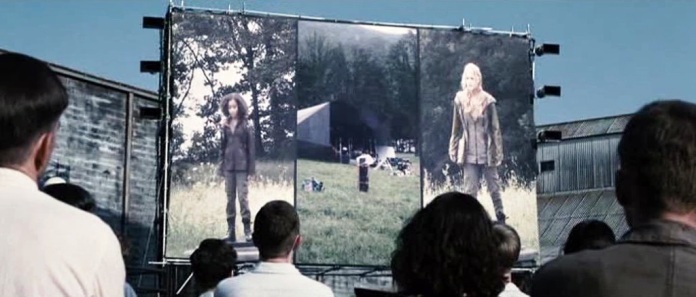

Since a rebellion many years before against Panem’s ruling elite in the Capitol, a sacrificial tournament is held every year in which a boy and girl tribute from each district has to engage in a gladiatorial fight to the death in a carefully prepared natural environment. At “The Reaping,” the lots are drawn for the District 12’s anointed duo; in spite of the stacked decks of economic necessity that mean Katniss and Gale are far more likely to have their names drawn, it’s Prim who is chosen. Katniss frantically volunteers to take her place, and she and male pick Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson), the son of local bakers who once did Katniss a good turn, are initiated, albeit briefly, into the decadent lifestyle of the Capitol, where they’re manufactured into fitting media idols for the duration of the Games. You see, it’s not simply one’s survival skills that can affect the outcome, but one’s direct appeal to an audience of potential sponsors who can pay to have desperately needed items dropped into the battle zone. Katniss and Peeta are prepared, in varying styles, for their oncoming ordeal by their appointed mentor, District 12’s only living Games winner, Haymitch (Woody Harrelson), and the surprisingly empathetic Capitolian stylist Cinna (Lenny Kravitz).

Ross was clearly chosen for this project on the back of his previous works as director, the obvious fantasy satire Pleasantville (1998), where the destruction of oppressive regimes is relayed through media images, and Seabiscuit (2003), where scrappy underdogs triumph in a time of privation. Ross’s direction, as with those previous films, is often facetious in its cinematic techniques, if also well-calibrated in places. Such is true of an hallucinatory sequence where, affected by the sting of genetically engineered wasps, Katniss dreams of her father’s death, and a patch of raw impressionism in the first moments of the games: the well-trained Tributes from richer districts for whom competition is an honour brutally exterminate as many competitors as possible, scored to an eerie piece of ’70s experimental music. Both of these scenes hit the right note of apocalyptic dread.

But elsewhere, Ross reveals an inability to create a truly textured mise-en-scène or sustain real tension, badly corroding the story’s basic strengths. What’s supposed to be the acerbic portrait of the Capitolians as a race who have taken plastic surgery and body modification to infinitely more ludicrous levels is poorly rendered: Ross’s Capitolians look more like art students attending a New Wave dance club circa 1982. Where a cleverer director with a stronger sense of staging might have presented a jarring intrusion of super-technology into what is otherwise a 1920s mining town, Ross casually tosses it at the screen, much like he does with the disorienting contrast of the ludicrously dolled-up Effie Trinket (Elizabeth Banks) and the drab environs and populace of District 12. It’s a warning that the kind of superficial realism Ross tries to invoke with his jittery hand-held camerawork doesn’t always suit tales where the need to absorb surface contrasts is part of the dramatic texture, never mind futuristic fantasy-action-satires. By contrast with the environs of District 12, smartly utilising the real detritus of modern industrialism, the Capitol is a hunk of unspecific CGI, and flatly derived contemporary televisions graphics are proffered to fill out this curious future brand of reality TV. Characterisation of the archly artificial Capitolians that ought to blend with supple anxiety and personal insufficiencies, like Effie and Stanley Tucci’s smarmy TV host, are steamrollered into mere theory.

Ross is a “serious” filmmaker, and he puts his broadly successful main effort into taking Katniss’ terror and bravery earnestly, but the film deals with her background and history in District 12 is such cursory terms that Katniss is reduced to little more than a pretty, bland protagonist. Her nominal toughness and strength of character are barely troubled by any depth, only a kind of blank stoicism, and her love for her sister is signalled with tepid devices. Ross leans entirely on Lawrence to flesh out Katniss, a reasonably smart move as Lawrence delivers, but not therefore a forgivable one. Her attitude is conveniently laid out for us when she retorts to Peeta’s stated desire that he find a way to remain an autonomous moral unit in the Games, “I can’t afford to think like that.” Of course, the film will constantly undercut Katniss’ expedient sensibility first by making sure that the only deaths she has a hand in are mercy killings or entirely deserved in the name of self-defence against creeps. The set-piece of grim, wrenching loss in both book and film is the death of Rue (Amandla Stenberg), the youngest of the Tributes who reminds Katniss of her sister and who is impaled with a spear by another tribute trying to kill Katniss. The film’s most interesting addition follows: because Ross can’t quite get across how Katniss deliberately turns her funeral for Rue into an act of political theatre because he cannot offer any technique that gets into her headspace, he provides instead a literal result, a riot in Rue’s home district sparked by fury over the girl’s death and Katniss’ gesture of solidarity.

Collins’ novel, whilst many miles from being a literary masterpiece, utilises its first-person, present-tense style cleverly to lay out a tale that engages with a modern phenomenon, the layering of media that’s pervasive in a world where it’s possible to experience, record, and critique experience all at once, and where internal and exterior realities can be disconnected in some puzzling and alienating ways. This is accomplished through Katniss’ constant meditations on the opacity of Peeta’s motives as well as her own, and the necessity of playing up to the crowd before, during, and after the Games. The idea is deepened in the follow-up novels, in which Katniss is constructed in variations of media idol as required by the moment and the authorities laying claim to her. This is the new element Collins brought to the basic story, which has roots in prehistory but which comes to us most clearly from models like Richard Connell’s oft-filmed story The Most Dangerous Game and Cornel Wilde’s rough-hewn classic The Naked Prey (1966): the basic point of such tales is that if you strip down the average human and place them in a situation of animalistic, life-and-death struggle, you find something both frightening and pure, even noble.

More recent works with similar motifs, like Rollerball (1975) and The Running Man (1986), added the idea of such battles being media events, taking place under an incessant, totalitarian scrutiny. Collins’ tale, through the way the Games are constructed as instant media artefacts, moves beyond such templates, as even in situations of ruthless combat and mortal struggle, there’s an element of psychological duplicity, of unreality: even a battle to the death can still be punctuated by worrying about achieving the right pose and losing your audience appeal. When I, like many others, first heard of the Collins tales, the likeness to Battle Royale seemed inescapable, but upon actually reading The Hunger Games, I immediately realised there’s little actual similarity—ironically, to The Hunger Games’ detriment. Battle Royale presented a ruthlessly cunning metaphor for the pressure placed upon students to conform and perform, and dug with insidious brilliance into the dark side of being adolescent—the operatic emotional intensity, the protean fluctuations between pure ardour and utter hate, the way petty social interactions and competitions can stir outsized reactions.

The Hunger Games, by contrast, essentially treats its central conceit like an interschool sporting event, tossing people who don’t know each other into a cauldron. The film barely introduces the other Tributes, most of whom are just glowering, smug hunks of threat. That was egregious in the book, too, but at least the first-person perspective made it acceptable. Ross violates that perspective at any opportunity, chiefly so he can use the Games commentators as exposition spouters. The sight of the most skilled and ruthless Tributes, who form a unit to pick off Katniss, calls to mind a pack of prefects hounding the solitary misfit on a school excursion and has some punch in evoking true high school dynamics, but this is throwaway. Whatever relevance The Hunger Games has to its target audience is all but surgically removed beyond obvious placards like “rely on yourself” whilst “sometimes working together is good.”

Also banished is any real political significance, as Panem is left such a vague and specious dystopia as to make the film’s pretences to commentary on haves and have-nots (or the 1% and 99% to put it in laboured contemporary slogans) thin to the point of meaninglessness, especially considering that the film cops out of implicating its audience in the acts of watching thrilling blood sports for entertainment. In the novel, the social structure of Panem is left fairly vague, and therefore the situation of Katniss and fellow Tributes has a faintly Kafkaesque quality of random victimisation by unseen forces; here the villainy is given specific shape by fleshing out the evil President Snow (Donald Sutherland) and the chief of the “Gamemakers,” Seneca Crane (Wes Bentley). Sutherland, who’s as sublimely menacing in his leonine fashion as he’s ever been, aptly links the film to a cinematic history of anti-establishment films like The Dirty Dozen (1967) and MASH (1970), which is odd, because otherwise, The Hunger Games represents the franchise film without specific history or future, only the necessity of the moment’s dollar.

Collins’ novel offered a fascinating take of the ambiguity of some youthful rites of passage: Katniss’ engaging in a play-act with Peeta that may or may not be a play-act, for the benefit of success in the Games and also because Katniss is still essentially learning who she is. By going through the motions of certain experiences, she channels a common way young people engage in self-discovery, more common than is often noted. This theme is completely lost on screen. The film even sucks away some of the book’s wryer touches that offer thematic heft, like the way Katniss begins to feel the pull of the hated exceptionalism and decadence of the Capitol’s lifestyle as she’s waylaid by plentiful food and the beautifying treatments and styling Cinna gives her. Cinna’s own most memorable line of self-assessment that offers the hint that not all is well amongst the Capitol’s citizenry, “How despicable we must seem to you,” fails to make the cut, too. It’s no wonder pundits of both left and right have been able to lay claim to the film, because it’s so equivocal as to be practically a Rorschach test for the viewer’s specific viewpoint. The Hunger Games has and undoubtedly will continue to inspire a suitable welter of articles in magazines and term papers about empowerment for young women, metaphors for the global financial crisis and third-world poverty, reflections on social networking and reality television, and blah blah fricking blah. This is the perfect material for our era where subtext has become, well, text, the theoretical turned into pedagogic narrative literalism without real entertainment value.

Ross and Billy Ray cowrote the script with Collins herself, and the film follows the novel with a painstaking refusal of new imagination, and yet it still manages to leave out much that made Collins’ work specific and original, and rushes not only the scene-setting opening but also the interestingly off-beat, melancholy conclusion. After decades of complaints about filmmakers ruining novels by changing them, today filmmakers ruin novels by adapting them with scrupulously lead-footed fidelity, as if there’s no essential difference between literary and cinematic narrative techniques. Rather than intelligent synergy, what we get is rote extrapolation of the good bits (Katniss shooting the apple from the roast pig’s mouth to shock the Gamemakers; dropping the hive of mutant wasps to see off her persecutors) without any care for narrative sophistication or novelty, leaving only a glorified TV pilot. There’s so little nimbleness, wit, concision, and visual pleasure in this film that it begins to feel like a chore to get to the end of it. There’s something about these carefully packaged franchises based on hit novels that’s becoming increasingly stultifying, being as they are essentially two hours of moving fan service rather than independent-minded cinema. Whereas that was acceptable with the Harry Potter novels, which, with their intricate plots and their overflowing delight in a fantasy world, both enabling and offering relief from mere plot, a neat correlation is now established: Hollywood gets to milk every last dime in exchange for fans, that ever-nebulous body that is today regarded as a body of sacred worshippers, especially if they’re young.

Perhaps all this wouldn’t mean too much if The Hunger Games, which is basically an action-adventure tale in spite of its pretensions, was actually any good as an action-adventure movie, but it’s simply passable in that regard. Whilst the moment of Rue’s death is leveraged for maximum impact, it’s so carefully arranged to leave Katniss free of any implicit guilt and absent any sense of physical pain that the effect is calculated and mawkish, as if the filmmakers have no sense of the irony implicit in the scene. The film’s best moment of violent epiphany comes when Katniss is defeated by one of her more evil opponents, a knife-hurling girl named Clove (Isabelle Fuhrman), who, taunting Katniss about the death of Rue, earns the wrath of Rue’s district fellow Thresh (Dayo Okeniyi). He beats her to death, her wide-eyed corpse falling to the earth besides Katniss in the sort of moment that carries the authentic jolt of supercharged emotion blending with the sudden switch between villain and victim such a situation must entail. But the moment doesn’t count for much—a flaw shared with the book—because the other Tributes are all functional cyphers who give shows of wickedness, emotion, and mercy precisely when it’s required for our heroine’s sake, whose nominal qualities are, again, constantly undercut by external chance and happenstance when it comes to staying alive. Even the moment when Katniss decides to defy the Gamemakers in their final cheat, and proposes that she and Peeta poison themselves, is clearly signalled to be her cunning plan, assured to end positively. Lawrence shares barely any chemistry with her unremarkable young costars, so any proto-erotic frisson is irrelevant. I began to find myself, heaven forbid, actually missing that gauche, girly, campy enthusiasm that drives the Twilight tales, where at least there’s supposed to be some pleasure in the fantasy.

The novel’s bizarre climax, when the remnant Tributes are hunted by dogs genetically engineered with DNA from their dead fellows, a concept and image with truly Sadean ramifications, is rendered dead on arrival because Ross shoots it in the dark. Which made me newly conscious about one aspect of this type of movie: whilst The Hunger Games goes through the paces of making itself coherent to an audience of newbies, for people who know the book, it essentially relies on them to fill in all the blanks it leaves. Of course, none of this is to say that The Hunger Games is bad: and no, it’s not bad. But it still manages to amplify the faults of its source material and add more of its own. In the end, it is competent and sufficient, and, all things considered, that’s what’s truly, dismayingly disappointing about it. Still, it’s not just Lawrence who emerges with dignity intact: Kravitz is surprisingly good as the commanding, yet gentle Cinna, and Stenberg is unforced in her embodiment of plucky, doomed youth. On the other hand, Harrelson and Banks, often amongst the better things in movies they appear on, get barely any chance to suggest pathos for their characters. Perhaps this series will improve in its later chapters, especially the dark, “meet the new boss, same as the old boss” kicker in the last episode, but only if it learns the same lesson as Katniss does. It’s not enough to merely turn up and act tough. You need a good stylist, too.

I found this to be so atrocious visually that I could barely get past that aspect of the movie. Almost no shot held longer than 10 seconds, constantly moving camera, too many close ups, I actually found it somewhat painful to watch. I could never just dwell on what was on the screen, I was constantly adjusting to a new shot, a new angle. I found myself wondering what Ross was hoping to achieve with that style, and if he had the slightest clue just how annoying it was (clearly not). Even Paul Greengrass, who I don’t care for too much, at least takes a periodic breather from the hyperactive camera movement and editing, while Ross never took a break, I think he was trying to wring something out of every scene (somehow), when he really needed to settle down visually once in a while and let the viewer relax a little bit. I was happy to see that Ross was either fired or took himself off any sequel, although it’s doubtful I’ll go see any further offerings. After I got home from this thing, I watched part of “The Aviator”, whatever the merits of that movie, the look is about a thousand percent better than Hunger Games, it was quite a contrast to see The Aviator immediately after Hunger Games.

LikeLike

Hi Patrick. It’s a damnably irritating-looking film for the most part. A lot of people have put some of this down to the relatively cramped budget and rushed production of the film – perhaps mostly the latter – but that’s a weak excuse when much smaller films have more memorable dystopias to offer. God I wish Neil Marshall had made this. What gets me is the fact that the film is over two hours long and yet it still manages to gut the substance of the book and flail so badly when it comes to communicating esential story elements. I would look forward to the sequels, myself, because the 2nd and 3rd books are by and large better, and the fact that Simon Beaufoy’s writing Catching Fire is promising, but Francis Lawrence as director is a dreadful prospect, and I get the feeling this is one franchise where relentless expedience is going to trump all. I myself crawled into a Terence Fisher movie afterwards for recalibrating. And whilst The Aviator isn’t one of Scorsese’s greatest films, any five minutes of it has more visual pleasure than 90% of what modern Hollywood puts out put together.

LikeLike

This is a great review, Roderick. I pretty much agree with it completely. The only thing I would quibble with is your preference for the sequels over the original book. Personally, I found all the books to be pretty unrelentingly intense and therefore hard to put down, but after going through all three in a few days, I was left feeling uncomfortable and unsatisfied. The first book does, as you say, let Katniss off the hook a little, but simply as a reading experience it’s more enjoyable than the other two, with a punchier plot and better pacing. The other two get all wrapped up in plot complications and world exposition, and the convoluted ways they bring the hunger games/arena battles back into it are really irritating, as is the horribly drawn out love triangle.

Not that I hate them or anything, but I also really felt that while they get more and more thematically complex, they gave up an element of humanity and warmth. The trilogy has hardly any humor, the later books introduce very few well-drawn characters, and overall it kind of felt like I was wallowing in a world of unrelenting nihilism and violence. I get that that’s kind of the point, but if I was going to have my kids read a wildly popular book series, I would absolutely stick with Harry Potter. Rowling sees people as capable of nobility and the world as capable of true beauty, and she leavens her tale with humor, dozens of fantastic characters, ever-expanding imagination, and a genuinely rich sense of life. Collins sees individuals caught in the system, ripped apart by governments and war, incapable of free action, where love and tenderness are fleeting things, ultimately incapable of genuine meaning or hope. Also, Rowling understands there are moral and spiritual spheres to life, Collins seems almost completely materialist.

Plus, is it just me, or is Collins sometimes a really vague writer? There were several points throughout the series where she would describe an area or object to set the scene, and I would form a picture in my mind, then half-way through the scene she would describe something happening that could not possibly happen in the picture I had. When I went back to read the description, I always felt it was her fault, not mine–highly distracting, and suggests she’s so in love with the terseness of Katniss’s voice that she doesn’t bother to explain things thoroughly.

LikeLike

A fabulous thorough-going analysis. What troubled me was that the film left the audience off the hook. The viewer can identify with Katniss and all these good young adults because the protagonists have no will of their own to speak of. They are forced, compelled to do battle, and kill, by a Totalitarian government. It leaves the sneaky impression that if young people could just be left alone, free of adult authoritarianism (at school, at home, in the world at large,0 the world would be an ideal place.

Finally I think Stephen M nailed it with his contrasting of Ms. Rolling’s world-view and Ms. Collins’ world-view.

Congratulations to you both!

LikeLike

Shyness forbade me from mentionining that I also posted a critique of The Hunger Games at my blog. If you get the time, would love for you guys to read it and hear what you think. Best

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting, Stephen, Stan.

Stephen, I do understand your objections to the follow-ups even if I don’t share them: I gave a groan when I realised in the second book that Collins was going to commit the Death Star heresy, but call me a fan of “plot complications and world exposition”. Personally I found Catching Fire‘s the faster-paced entry, and the games more authentically dizzying in their viciousness, plus the sensation that not all was it seemed, which crystallised towards the end, was for me much more compelling. I also enjoyed the addition of Finnick and Johanna, as they brought in a quality of complication to the formerly neat moral categories of the Tributes, although Collins later ruined Finnick a little by making sure he turned out to be a tragic romantic, because obviously no-one who’s flamboyant and likes having sex a lot can be good. The second two novels are certainly far darker and oppressive, but maybe that’s a good thing. For myself, when I was a teen I almost never read “Young Adult” fiction, because I found it simplistic and stuffed with pedagogy and I fancied myself above “positive messages”. And this series is definitely for the teens inclined to stave off Harry Potter as kid’s stuff, and look at this as real meat, and I can see the attraction. Collins seems conscious that she was constructing a series for teens (not kids; in spite of the idea of the Harry Potter series growing up along with the characters, they still essentially remained friendly for quite young audiences, very naive and cute by the standards of the modern 16-year-old, at which these are aimed: when I was sixteen, I’d been reading Tolstoy and Sartre, and friends were devouring Stephen King and Anne Rice and other very non-positive messengers) who are aware of the world, have grown up with the Iraq and Afghan wars and 9/11 on television, might be interested in the Arab Spring (and indeed might even be participating in the Arab Spring), and will recognise that the world can be a dark and vicious place, wars rarely things of pure Manichaean hues. And these stories at least might make them a touch less inclined to swallow the horseshit of Bush and any others in the future. I disagree there’s no moral sense – there is no spiritual sense, but that I can take or leave – as there is in the second two books a consistent portrait of Katniss’s sense of the consequences of her actions and the anguish of sliding into the same kinds of behaviours one loathes in one’s enemies. But Collins’ ambiguity, at least in the first book, is a little like the false “ambiguity” of The Dark Knight, where the enemy is so ugly and unremitting, and the causes of the conflict so clear-cut, that the hero’s own quandaries are simply a pretence, a raising of a question that is more solipsistic than conscientious: the idea of being guilty over sparking a violence in an opponent that has always been ready, willing, and gleeful to unleash that violence is bit like being a mouse guilty over upsetting the trap about to break your spine.

That said, I do agree about Collins’ occasionally fuzzy writing. I’m never too fond of that very verbal, conversational writing that seems de rigeur for these things – it’s certainly nothing like the writing style I’ve been trying to perfect – although it is “easy to read”. I just never asked for ease in reading.

Stan, a visit to By Film Possessed is always worthwhile (great looking site too), and I’m interested in your comments (also, you quoted Denby’s review, which I agreed with practically word for word when I read it originally). I’m not quite such a Lord of the Flies adherent, but yeah, there’s a desperate lack of that tale’s insight into the latent primitive in the young, and the sense of wildness and darkness from living on the very edge of mortality.

LikeLike

Rod,

A fine analyis. I galloped through the trilogy of books in pretty short order, and had a very positive initial impression of the film. However, the impact of both the books and the movie both faded pretty quickly after reading/viewing , I believe for all the reasons you’ve outlined here – patricularly the lack of moral complexity in the lead characters (especially Katniss).

Ross apparently got the gig on the strength of a video he made of himself interviewing teenagers about their reactions to the book and was approved of by Suzanne Collins herself. For me, the key to Ross’ take on the material is summed up in an interview quote from Jennifer Lawrence: “He understands that it’s a sad story, not a cool action flick.” That’s a noble point of view, but it only gets you so far with this material (and it certainly won’t work for the upcoming, more action-driver chapters in the trilogy.) By backing off the more brutal aspects of the Games violence – in particular, significantly reducing the severity of injuries that Katniss and Peeta sustain in the film version – the impact of the Games and their consequences is muted and all but lost.

LikeLike

Hi Pat. Well said. Of course, it’s possible to get over-intellectual and too demanding over this sort of thing – and generally as I like my action-adventure smooth on the palate – but the series so clearly and ambitiously invokes deeper and more troubling things it seems fair to ransack it intentions and devices. That’s an interesting anecdote about how Ross got the job, and Lawrence’s comment, but neither really makes up for the fact that Ross is an obvious and flat-footed director. Young audiences deserved to see in Katniss a distaff version of Bruce Willis in Die Hard – limping, bloody, dishevelled, close to total collapse, but still determined and defiant. That’s the sort of hero you really cheer for. Still, when a film’s made $500 million, no-one’s going to be listening much to the dissatisfied.

LikeLike

This has been a very hectic week for me Rod, and as a result I’ve had to run through the blogs I frequent. I count myself as a fan of THE HUNGER GAMES concluding that square can be beautiful too, and that the film is briskly paced, engagingly plotted, impressively designed and acted, and boasting a futuristic story that while not quite as provocative as it could have been, still resonates intellectually and emotionally, and makes some apparently wise alterations on the novel it is adapted from (one I have not yet read). I do understand your issues in regard to the amplification of the source material and also that while you have issues you acknowledge it’s decent enough. As always a remarkable, provocative essay.

LikeLike

Much thanks for the encouraging words and comments. Best.

LikeLike

Well Sam, thanks for commenting in spite of your busy schedule, but I still have to take issue with your saying this was well-designed. It really, really wasn’t. I’ve seen Jesus Franco movies utilising late ’60s brutalist architecutre that seem more dynamically futurist than this. And no, the changes from the novel are not particularly wise.

LikeLike

Rod, the costume design was lazy, yes, I’ll concede that. However as to the matter of set design this is really a matter of opinion. Ross’ admirable application of minimalism worked to create a believable dystopian society, devoid of the kind of excess that would normally malign this kind of movies. I bought it myself, but I well understand it won’t work for everyone, especially those who aren’t thrilled with the movie in the first place. I have been told by teaching colleagues who did read the original novels that the alteration were smart. That’s basically what I was going on here, couples with my perceptions of how the story arc ultimately played out.

We’ve agreed quite a bit lately, on this film we’ll just have to strongly disagree. It’s not ‘Top 10 of the year’ great, but it’s still exceptional for what it is.

LikeLike

Well it’s nothing to get hung about. I suppose you’ve been busy at Tribeca, Sam.

LikeLike

Indeed Rod, this is minor stuff. Yes Tribeca has been sizzling, and the best film I’ve seen of the 20 (with five more to go) is the powerful, poetic and hauntingCanadian work WAR WITCH, which just today deservedly won the Best Narrative Film by the jury:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/film-news/9231178/War-Witch-the-film-making-waves-at-Tribeca.html

I can’t wait for this to eventually get the “Roderick Heath treatment.”

LikeLike

I saw that won – sounds very interesting. I wonder how long before it’ll show up in my neck of the woods?…*sigh* Anyway, glad the festival’s top-notch.

LikeLike

It shouldn’t be long Rod. The praise it’s received should ensure it will get full distribution.

And I must add that if I were a betting man (I am sometimes) I would bet the farm that Marilyn will come in with a strongly positive reaction. It’s a movie she would write a masterpiece on, methinks.

LikeLike

This is the longest review i’ve seen in the past 2 weeks about this movie and i have to say that this one is the most accurate, great work love it.

LikeLike

Well, accuracy does require depth, and depth requires length, Tranquillo. Thanks for commenting.

LikeLike

I haven’t read the books, but I sensed the film was doing them a disservice. I found Rod’s analysis acute; he articulated a lot of what I was feeling, but was struggling to coalesce into language.

Amongst other problems, I found the film to be oddly sexless. Nobody seemed to as much as notice all the hard teen bodies around them.

LikeLike

Sorry Jeremy, I didn’t see this because it was shuffled in with all the Drums Along the Mohawk comments. Yes, sexless is darn accurate; I suppose the narrative is supposed to work like this – there isn’t all that much time for sex when the anxiety of being killed in the morning. But that’s…not especially convincing, considering that “we might all die tomorrow” was the great chat-up line of WW2 and the Cuban Missle Crisis. Rather, it’s just another aspect of how the film secretly hews to conventional, tidily conservative morality whilst pretending to disperse it.

LikeLike