Director: Nicholas Meyer

The Days of High Adventure: A Journey Through Adventure Film

By Roderick Heath

It might seem like a leap from the earthbound historicism of The Sea Hawk to the second instalment of a 1980s TV-derived scifi franchise, and yet they’re both, essentially, pirate movies. Lately, pondering the synergy of elements necessary to create great adventure films, I had to admit that, in revisiting Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan (the numerical was added after initial release), I saw it has just about all of them: wonder, action, character, myth, darkness, depth of concept and execution, originality and also noble cliché, a sense of fun, and a sense of legacy, both future and historical.

Gene Roddenberry’s adored TV series “Star Trek”, which ran from 1966 to 1968, ironically became a much bigger hit after cancellation, through syndication showings in the ’70s. The show possessed a ragged, trippy, perfervid energy and channelled scifi’s essential creeds and some fresh ideas into some generically familiar archetypes, stereotypes, and situations—not for nothing did Roddenberry label it “‘Wagon Train’ in space” when pitching it to execs. It survived in part because it channelled a post-counterculture hunger for New Age ideals and inclusivity into a futuristic context, and resulted in the birth of the Trekkie, still the emblematic scifi fan of a fiercely loyal and sometimes obsessive breed. So strong was the series’ belated following that an animated series resulted, and then a push for a movie edition, which reached fruition after the success of Star Wars (1977). The initial result, Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), directed by that sturdiest of old pros, Robert Wise, modelled itself after the show’s more inquisitive episodes, whilst pinching liberally from Arthur C. Clarke. Wise’s sense of visual grandeur and the probing script partly made up for an uncertain reintroduction for the old cast and a distanced sense of the series’ familiar human element.

The general feeling was that the result was a flabby disappointment. Roddenberry’s fussy creative control got the blame, and it’s clear in retrospect that he was trying to revive his creation with a tone anticipatory of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994), which, with its ponderously plastic air and drones for heroes, was still similarly curious in its best moments. The Motion Picture made enough money to warrant a sequel, but for the second spin around the galaxy, producer Harve Bennett hired a fresher director with a zippier understanding of the underpinnings of such feverishly followed cult works. Nicholas Meyer started off as a writer, with the likes of the campy comedy Invasion of the Bee Girls (1972) and the novel The Seven-Percent-Solution, adapted by Herbert Ross for the screen in 1976, before he made a directorial debut with Time After Time (1979). Meyer revealed a grasp on the minutiae of figures like Sherlock Holmes and H. G. Wells, and understood the curious nostalgia that resided within the survival of those characters, revelling in the ironic contrast between the Victorian sensibility that spawned them and the modern perspective on their charm—a sensibility that was ironically similar to the inner, fantastical spirit of Star Trek.

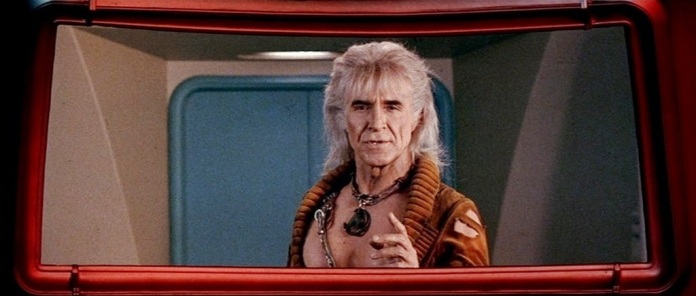

Certainly, the catchphrases of Star Trek, like Spock’s “Fascinating,” were becoming as specific as Holmes’ “Elementary,” and Meyer understood that. Meyer responded to his new job by going to school on the original series to carefully recreate its essentials, and did an uncredited overhaul on Jack B. Sowards’ script. The Wrath of Khan was perhaps the first film to provide a nominal sequel to a TV episode, 1967’s “Space Seed,” in which Ricardo Montalban had guest-starred as Khan, a genetically engineered superman exiled centuries before from Earth with his followers, who, when salvaged by the Enterprise on its five-year mission, tried to take it over. They were defeated and left to start a colony on a new planet. Whilst such continuity tickled series fans, having seen “Space Seed” was in no way necessary to understanding the plot of the movie. Indeed, it was slightly confusing, as Khan had never met Enterprise crewman Chekhov (Walter Koenig, who joined the old show after “Space Seed”) but recognises him here. Khan was reconstituted in the film as a phantom from the past of James T. Kirk (William Shatner) who emerges to torture and terrorise him precisely as he’s looking down the barrel of a dull and barren middle age, his swashbuckling days as a space captain behind him.

The Wrath of Khan is today often beloved for its moments of unfettered camp, and yet it’s actually a deftly balanced work: warm, funny, dashing, often tongue-in-cheek, and yet emotionally and intellectually quite earnest, filled with lush, spacious imagery and well-paced action. It’s a film that manages to do many different sorts of thing at once, and for very good reason, it’s become a kind of code word for a movie series highpoint. Meyer gave Wise’s stately approach a kick in the pants, and whilst the same elements of wonder and speculative intelligence that The Motion Picture belaboured are still in evidence, here they’re carefully dovetailed with the onrush of a plot that’s more than a little like Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003) in space.

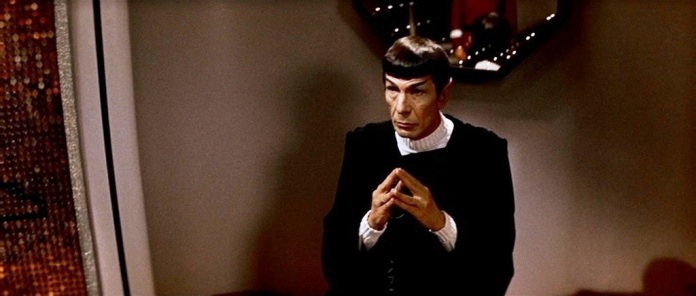

Meyer’s most personal and effective touch was to remake Kirk, Spock (Leonard Nimoy), and Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy (DeForrest Kelly) into men reminiscent of his earlier takes on Holmes and Wells. They are men out of their time, aware of retro paraphernalia and culture, offering a continuity with the geeks of Earth past, and possessed of an energy and idealism that’s all the more vital in a future world. The film’s very opening depicts one of Kirk’s prize pupils, Saavik (a pre-Cheers Kirstie Alley), a humourless Vulcan neophyte who nettles under the painful lesson of the “Kobayashi Maru,” a test that places potential officers in a situation where they have to find their grace under the imminent inevitability of death. As well as offering up a memorable fillip of series lore, the fact that Kirk administers the test which he himself successfully subverted in his student days presents a thematic echo that rings out through the rest of the story up to its tragic climax. Kirk, with his recurring refusal to believe in the kind of no-win scenarios the test prescribes, must face the real cost of such a situation.

Meanwhile, Chekhov (Walter Koenig), working under Captain Terell (the late, great Paul Winfield) aboard the Reliant, is searching for a lifeless planet to conduct a vast new scientific experiment with the fantastic new Genesis Device. Beaming upon a planet they believe to be the lifeless Ceti Alpha 6, they fall into the hands of Khan and his fellow survivors, who had been left to form a colony on that planet’s neighbour by Kirk: the planet is, in fact, their former Eden, laid waste by cosmic calamity, and they have only just clung to existence. Now mad for vengeance for the suffering of their exile and the deaths of his wife and several crew from attacks by native animals, Khan takes control of Chekhov and Terell with brain-infesting slugs and sets out to trap Kirk and take control of the Genesis Device. The device has been developed by scientist Dr. Carol Marcus (Bibi Besch), her son David (Merritt Butrick), and a team of researchers on a space station neighbouring the lifeless moon of Regula 1. The device is an incredibly powerful mechanism with the capacity to reshape planets into life-supporting spheres, albeit with the caveat that any life that exists there already would be obliterated, thus making it a work of terraforming wonder that could also be a terrible weapon. David is paranoid about possible military uses of the Device and interference by the Federation, and when Chekhov, under Khan’s control, messages the station ordering the Device to be handed over, pretending the order comes from Kirk, that paranoia seems justified. Carol tries to contact Kirk to demand an explanation, but her message fades out. The Enterprise, on a training mission for the young recruits, heads to Regula 1 to see what’s going on, only to fly headlong into Khan’s ambush.

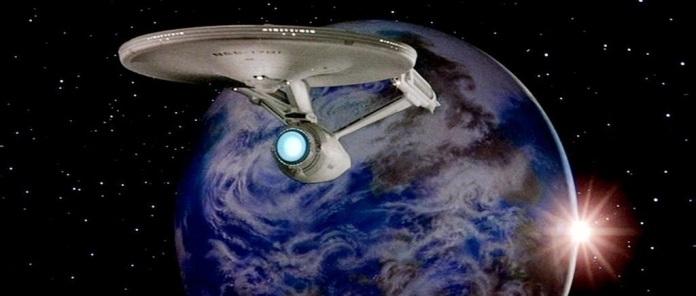

The Wrath of Khan‘s reduced budget impacted the quality of production noticeably, as the film littered with rather pasteboard-looking sets and props. There are some clunker line readings redolent of a rushed shoot, and Khan’s crew, all strangely much younger than him, look like escapees from a futuristic roller disco musical. But that’s all part of the fun, and otherwise, the film retains the polished look of an A-grade saga. The film’s colour is fleshy and colourful in an aptly pulpy fashion, thanks to Gayne Rescher’s photography. The special effects were done by George Lucas’ Industrial Light and Magic outfit, and included a ground-breaking use of computer-generated imagery for the demonstration film of the Genesis Device’s purpose. The effects are very uneven, and yet still possess an epic lustre. I can’t help but admire the suspense Meyer can wring out of scenes of grim-looking crewmen marching about with what look like vibrators with light globes attached: god knows what they’re going to do with them, but damn if doesn’t look important. Similarly, it’s fascinating how poetic the moment in which Carol brings Kirk into the cavern transformed into a paradise by the Genesis Device is, in spite of the obvious matte paintings, in a way that still dwarfs all the CGI landscapes of Avatar (2009). Much of the film’s impact, it has to be said, is due to composer James Horner, who two years earlier had been working on Roger Corman quickies before he gained notice for his mock-epic work on Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Horner’s soaring, seafarer-like score permeates The Wrath of Khan with a sense of galloping excitement and swooning awe in such moments as the Enterprise’s sailing out from it space dry dock and Kirk’s first glimpse of the Genesis cave.

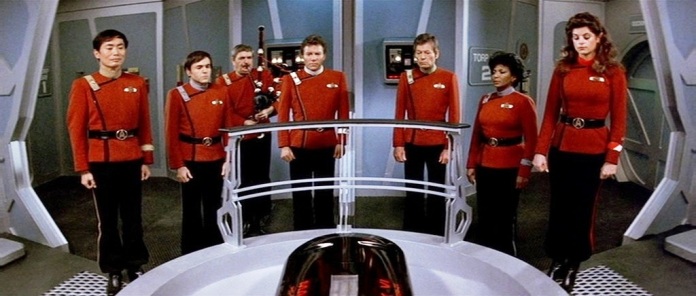

Whilst the series’ egalitarian, progressive ideals were certainly heartfelt, “Star Trek” simultaneously always sustained an element of retrograde, imperialist thinking in its assumptions, with a future universe where political stability is enforced by gunboat diplomacy. Khan’s name emphasises this aspect. Rather than revise the discrepancy, Meyer emphasises links with Victorian drama and an imperialist adventuring tradition. Kirk and Khan constantly quote favourite novels, Moby-Dick and A Tale of Two Cities respectively, whilst the story and visuals make reference to a charming retention of seafaring codes in space. The Federation uniforms (redesigned from the hideous things sported in The Motion Picture) make the crew look awfully like Redcoats, and a crewwoman blows a futuristic version of a midshipman’s whistle when Kirk first boards the Enterprise. Simultaneously, The Wrath of Khan does something the series, with its limited budget and effects, and episodic style, could never do properly, which was offer, at last, a genuine space battle.

So perfectly does The Wrath of Khan lay out a form of a swashbuckler that the number of similarities in plot and theme between it and Master and Commander demand a few moments to list. In both, the heroes fight off a superior enemy who gets the jump on them in an initial ambush. The emphasis on the battle of wits between captains is all-important. Spock and McCoy are to Kirk as Maturin is to Aubrey, presenting the schism of man of action and man of thought in the context of the supposedly well-oiled machine of these ships of war. The Genesis Device and resulting planet are equivalent to the Galapagos Islands as cradles of wonderment and new potential that excite that scientific mind, a mind which is stifled in being merely obeisant to militaristic exigencies. In both, the physical maiming of a younger crew member is a major tragedy and spur to action. An ambush is facilitated through one ship pretending to be another: Aubrey’s ploy of disguising his ship as a whaler contrasts Khan’s use of a captured Federation ship to sucker in Kirk. Major acts of sacrifice are required to save the heroes’ ship: Spock’s fatal venturing into the reactor to repower the Enterprise matches Hollum’s suicide in belief he’s the Jonah that haunts his ship, and Aubrey’s hacking free a fallen mast, though its means a man must drown.

The Wrath of Khan builds story and character with a novelistic intelligence, as individual scenes that often seem discursive and casual actually contribute to the thematic imperatives of the tale. The opening joke, where the revelation that the chaos that engulfs Saavik’s captaincy is, in fact, the Kobayashi Maru test—McCoy, sprawled on the floor, demands praise for his performance—will inexorably lead to a moment where such chaos erupts for real around Kirk. He’s the only candidate who ever beat the test, and did so by creative cheating, and, of course, has to stare down the barrel of exactly the situation it was supposed to depict. Mortality is already weighing on Kirk’s mind at the outset, as it’s his birthday. Spock’s and McCoy’s birthday presents to the aging admiral are both antiques for his collection, a leather-bound copy of A Tale of Two Cities and a pair of ancient reading spectacles, apt for Kirk’s retro sensibility, but also reminding him of the march of years. The film actually lets us see Kirk’s apartment in San Francisco, as McCoy breaks out a bottle of illegal Romulan ale—that’s the sort of throwaway touch that I love and that gives this phase in the franchise real personality. McCoy warns him against letting himself become an antique, too, and to get back to captaining, not training callow recruits.

Saavik is posited as a potential love interest for Kirk: she tries to flirt with him whilst trying to understand the purpose of the Kobayashi Maru test, but proves fatally unreceptive to his sense of humour. But she’s also a potential replacement for both him and Spock, an heir to both their legacies. Carol, Kirk’s former lover, and David, actually his son, albeit one he’s barely had any contact with before, present shades of alternative lives he gave up in his love for gallivanting through space, and give immediate, personal flesh to the film’s recurring motifs of existence as a chain of creation and destruction, birth and death. In spite of the futuristic setting, The Wrath of Khan feels intimately contemporary to the early ’80s, as David’s outright contempt and suspicion for Kirk and the Federation channels obvious hints of the ’60s Generation Gap, whilst Carol’s decision to keep David in her world suggests the impact of feminism and new parenting options, leaving alpha male Kirk in a slightly befuddled mid-life crisis.

Meanwhile, the extraordinary potential of the Genesis Device seems to invoke all of the characters’ essential quandaries and capacities, promising both apocalyptic destruction and miraculous creation. Carol, to cheer up Kirk when he’s feeling depressed about the carnage that’s struck his ship and his son’s ferocious antipathy for what he stands for, ushers him along to take stock of a miracle: the grand cave within the Regular moon that she’s turned into a slice of Eden with the Genesis Device, her gift of maternal beneficence to all. Spock and McCoy, upon first learning of the Device’s existence, swing immediately into one of their classic ethical debates. Spock’s coolly measured curiosity striking sparks against McCoy’s fiery, knee-jerk humanism. McCoy mocks the Genesis Device by channelling advertising speak: “According to myth, God created the Earth in six days. Now watch out! Here comes Genesis! We’ll do it for you in six minutes!’ The thematic conflict of the human and the destructive is even acted out on the level of the canonical texts that preoccupy the characters—the shamanistic nihilism of Moby-Dick and the humanistic idealism and sacrifice that defines A Tale of Two Cities. Spock is, of course, the tragic hero, the Sidney Carton of The Wrath of Khan. His logical and unemotive persona, which McCoy always assumes to be inimical to humane concerns, proves, as Kirk croaks in delivering a eulogy for his dead friend, redolent of the most human soul. Spock, now actually the captain of the Enterprise, hands over command to Kirk without concern when crisis is nigh, reminding his reluctant friend that “You proceed from a false assumption—I have no ego to bruise,” and giving Kirk exactly what everyone knows he needs at the same time. Spock becomes the paragon of selfless action and finds his fulfilment of logic in the act of giving his life to save the Enterprise’s crew from certain destruction.

Spock’s achievement of a kind of transcendence paves the way for a resurrection (though Nimoy was actually hoping to jump ship permanently), befitting his new status as demigod. He thus fulfils the religious imagery that he’s been associated with since the first film, which found him engaged in a rite to cleanse himself of feeling in primal landscape. Spock’s nirvana overtly contrasts Khan’s failed attempt to become the Destroyer of Worlds. Khan, genetically engineered and clearly associated with a remnant spirit of Nazi eugenics and an accompanying übermensch mentality, his own constantly stated superiority itself is a kind of godhead for his supporters—“Yours is a Superior Intellect,” as their salute to him goes, and one which his lieutenant Joachim can’t quite complete in dying as both salute and curse—proves weakened by exactly the egotism that Spock resists. Khan’s ruthless intelligence proves constantly susceptible to elements he can’t master, and his monomaniacal focus, like that of Ahab whom he constantly quotes, proves both infinitely destructive and yet quaintly impotent. “I shall avenge you!” he promises the dead Joachim, suggesting that in spite of his brilliance, he’s got all the capacity to learn from his mistakes of a goldfish.

The film’s booming moments of melodrama, such as Shatner’s immortal scream of “Khaaaaaaaaan!”, are either flaws or strengths depending on taste, but surely a helluva lot of fun either way. More to the point, such touches are part and parcel with the film’s resolutely nonironic, defiantly old-fashioned air. Meyer invests the film with an outsized quality that seems distinctly operatic: indeed, Kirk’s scream comes at the conclusion of a sequence that builds like an aria, as the two bull males gibe and wound each other with a spiritual ferocity that befits the talents of Shatner and Montalban, each capable of being both very good actors and colossal show-offs. Montalban, at the time a prime-time staple in “Fantasy Island” and still showing off his marvellous physique at 62, latched onto the role with gleefully outsized zest and finally gave Shatner a run for his money as the franchise’s biggest pork roast. That said, “Khaaaaaaaaan!” notwithstanding, Shatner’s at his best in the film, swinging from flip, sardonic good humour to introspection to larger-than-life heroism with a few well-judged bats of his eyelids and shifts of the inimitable Shatner voice. If Spock is the film’s tragic hero, Kirk here finally ascends to something like warrior-poet status, conjuring grace notes of wisdom hard-won from tragedy and gazing at the Genesis Planet with a truly affecting sense of wonder and rejuvenated spirit.

Whilst it might be stretching things a little to call The Wrath of Khan an intellectual adventure movie, nonetheless, it is distinguished by the genuine intelligence that permeates through the various layers of its plot, character, and theme, and how the film plays them for dramatic value. The central, biblical invocations of the Genesis Device are then overlaid with the Christlike sacrifice of Spock, lending the film a mythopoeic quality of actual depth. Too many modern, action-oriented, scifi films today treat their specific genre’s basis, in science and inquisitive theory, as a source of glib MacGuffins. The contrast with J. J. Abrams’ entertaining yet comparatively shallow 2009 reboot of the series is constantly tempting: whereas that film treated its scifi gimmicks and pivots of plot with throwaway contempt or utilitarian purpose in the name of composing a straightforward adventure, Meyer wrings such flourishes and moments to heighten suspense. Thus, the key moments of the cleverness of the heroes are relishable in staging and impact: Kirk’s foiling of Khan’s apparently complete victory by taking advantage of his superior knowledge of the Federation ships, managing to remotely lower Khan’s shields and hit him with devastating and unexpected force; the rabbit-out-of-the-hat glee of the revelation that he and Spock have fooled Khan into thinking repairs that would take two hours would actually take two days by the simplest of ruses; and the final battle where, at Spock’s suggestion, Kirk taunts Khan into following him into the Mutara Nebula, where interference leaves the two ships blind and lacking shields. There, the greater experience of Kirk and Spock sees them best Khan by simply thinking in the three-dimensional terms that a spaceship offers, whereas Khan’s mind is stuck hopelessly in the 20th century, culminating at last when the nearly crippled and dying Enterprise can still sneak up behind the Reliant and pulverise it to a drifting ruin.

Even with Khan defeated, however, the danger is still not past, as he triggers the Genesis Device as his final apocalyptic stab at a pyrrhic victory: the device’s capacity to bring life means nothing to him, but it comes to mean everything for those left to behold it. In spite of the film’s wobbles, the contrivance of the finale, as the down-to-the-wire crisis demands Spock venture into a radiation-flooded room to restore the ship’s power, is nothing short of storytelling perfection. Meyer’s willingness to reach again for operatic heights is apparent in Kirk’s forlorn cry of “Spock!” as his hideously seared and dying friend makes his last salutary “Live long and prosper” sign through the Perspex that divides them. As his body is fired off in a photon torpedo tube in a scene inspired by a similar stellar funeral in Byron Haskin’s Conquest of Space (1955), “Amazing Grace” surges on the soundtrack as his casket plummets onto the Genesis planet at the same moment a sun emerges from behind: it’s like Wagner in space by this stage. The final effect, ironically, wasn’t entirely what Meyer was after, presenting rather a sop to old Trekkies who couldn’t stand Spock’s death being taken too lightly, and yet it gives the film its truly grand final lustre. The Wrath of Khan fulfilled not only the best elements of Roddenberry’s original series, but connected it to the oldest and most complete forms of adventure mythology, positing the struggles of its sky-shaking heroes in the context of the birth and death of titans and worlds.

Well, much as I confessed to being a Dark Shadows junkie in my formidable years, I am also a lifelong Trekkie, an affiliation that commenced with the beloved original series in 1966, and continue on with the films, of which this second entry THE WRATH OF KAHN vies with the sixth, THE VOYAGE HOME as the cream of the crop. Ironically, Meyer had never seen a single episode of the original series when he took on the assignment, and yet he infused the camp and human elements that made the show so fanatically revered by fans worldwide. For the first time, the singular humor and camaraderie played out in the script, and the charismatic Carlos Montalban -so effective in a highlight episode “Space Seed” – was perhaps the most memorable villains in all the films. I am with the fraternity who reviled the first film for it’s stilted qualities, and inability to connect with the characters (though Jerry Goldsmith’s spectacular score for that first entry remains one of the greatest ever composed for a film) and was so thrilled back in those long ago days when I entered a theatre to take in the old magic that had defined out three years with Kirk, Spock, Scotty, Bones, Uhura and company. And yes I completely buy what you are saying about the film being intelligent without necessarily standing as an intellectual adventure movie. I would also apply that reasoning to many episodes of the original series. For the record, I am also a fan of STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION, DEEP SPACE NINE and VOYAGER, and those THE NEXT GENERATION is just about equal to the original show in my affections, I’d still say the first was always dearest to my heart for the longer time. You really say it all here:

“Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan is today often identified by its moments of unfettered camp, and yet it’s actually a deftly balanced work: warm, funny, dashing, often tongue-in-cheek, and yet emotionally and intellectually quite earnest, filled with lush, fluidic imagery and well-paced action. It’s a film that manages to do many different sorts of thing at once, and for very good reason, it’s become a kind of code word for a movie series highpoint.”

But of course it’s a brilliant piece, one I hung with for every word. Live long and prosper my friend.

LikeLike

Excellent write up. I enjoyed the first film and think its reputation is unfair, but the second was far and away the strongest, and outside of budgetary limits for production values it had the most depth of character while also giving the characters their familiar rings. I will betray my true love for this movie with a note that the planet of Khan was Ceti Alpha and the space lab was Regula 1. I also thought Master and Commander was brilliant for what it was able to do, given it was not likely that any sequels would be green-lit. A very apt comparison to WoK.

LikeLike

Hi guys. PP, nicely spotted on those spelling peculiarities. The film does indeed stand pretty damn tall amongst the entertaining run of Star Trek films; I revisited The Search for Spock just after writing this, and whilst it’s much less rough around the edges – more even FX and actor-director Nimoy keeping a tighter rein on the actors – it’s not a quarter as dynamic and driving as this one. That said, I too have developed a certain liking for the first film, which, if one goes with the flow of its serious and elegant tone, has many strengths, and some loud clanging weaknesses too.

Sam, at least we’re closer on this than on Dark Shadows! I’ve just never been able to feel the same affection for the subsequent Star Trek spin-offs from ST:TNG on. I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion that it’s the qualities of the original series and these films that most embarrassed Roddenberry and many Trekkies that I in fact love. Not that I want to pick a fight with fans of the subsequent series; there were many things to like about ST:TNG, including the consistent intelligence of its writing: some of its best episodes were like Holmesian detective tales in a sci-fi context. But I could barely raise an eyebrow for the cast apart from Picard and Data and, much more occasionally, Whorf and Geordie. And I could never get at all into the later series. Part of that stems from that sadly generic TV sci-fi look that infused those shows and others in the mid-’90s. One could change the channel from Deep Space Nine to Babylon Five and a couple of others from the period, and think they were all the same damn show.

This article by Mark Simpson, BTW, has become a bit of a bible for me in thinking about the generations of Star Trek:

Captain Kirk’s Bulging Trousers

Live long and prosper.

LikeLike

First I’m a huge fan of Wrath and remember watching Master & Comammnder and getting a serious case of deja vu.

LikeLike

Ha! And there I was thinking I was the only one who’d noticed.

LikeLike

“The film actually lets us see Kirk’s apartment in San Francisco, as McCoy breaks out a bottle of illegal Romulan ale—that’s the sort of throwaway touch that I love and that gives this phase in the franchise real personality.”

Well said! This is one of the things that I love so dearly about this film. The quiet, human moments that gives us insight into Kirk and his friendship with McCoy. Most films nowadays would do away with a scene like this as being extraneous and unnecessary but on the contrary it is vital to getting us invested in Kirk’s dilemma of getting old and becoming obsolete vs. going back out there and mixing it up in outer space once again.

I also love, love, love the literary references – the quoting from MOBY DICK and A TALE OF TWO CITIES… you can see Shatner and Montalban relishing this dialogue to the fullest. Great stuff!

LikeLike

The quiet, human moments that gives us insight into Kirk and his friendship with McCoy. Most films nowadays would do away with a scene like this as being extraneous and unnecessary but on the contrary it is vital to getting us invested in Kirk’s dilemma of getting old and becoming obsolete vs. going back out there and mixing it up in outer space once again.

Hell, yes; it’s the sort of thing that makes this an engaging ride, which too many modern films in this style do neglect, and more than that sticks in the mind as the very soul of this franchise. It helps of course that the characters already have such a legacy, and yet I think even to someone who just walked into the series at this point, something of the same point would engage the viewer. I miss films that tried to balance themselves like this. Yeah, the Shat and Montalban relish those quotes in their dialogue, maybe a little too much, but still, those moments are relics from an era when films could still assume their audience weren’t total goddamn morons.

LikeLike

Rod, your essay came a day after I started thinking on the film for a podcast with a friend (which I recorded today). I almost didn’t follow through with the podcast after reading, of course, as your essay is so much more thorough and composed than our conversational podcast could ever be. But I did it anyway. I hope you don’t mind, I gave you and this site a shout out (to the couple of people who listen) upon mentioning the similarities of the film to a classic adventure story.

Also, a few thoughts upon my most recent viewing.

1) Regarding the possibly throw-away apartment scene: it struck me for the first time how deeply it plants the idea of Kirk as totally alone, without a family of his own, save for the family that abides on that ship. He literally is married to his career and, as long as he’s an admiral, is in a permanent separation from his true home. The setting of that scene makes more resonant his later dialogue with Carol in the cave, that seeing her and David is like seeing “my life that could’ve been… and wasn’t.”

2) Meyer, et al, have allowed Kirk, maybe truly for the first time, to be a little unsure of himself. On the show, he usually seemed sure of how he’d get out of a situation, even if the audience wasn’t. Here, his character is shown to be more last-minute and desperate in moments of crisis than ever before. There’s more than a little of the previous summer’s Indiana Jones in Kirk’s expression when he turns from the first encounter with Khan and says he just “got caught with his pants down.” I wonder if some of that film’s embracing of a character “just making it up as he’s going” didn’t rub off on the writers of this film.

3) Similarly, the movie prefigures some of the earthy, improvised take down of the bad guy of the following year’s Return of the Jedi. Methinks there was some Beach Boys/Beatles mutual influence going on amongst these filmmakers.

4) The movie works so perfectly, insofar as its themes of death/rebirth, youth/old age, “life from lifelessness”, thanks to how fluidly and humorously those themes are set up in the first part of the movie. They may seem on the nose on paper, but the fact that it’s Kirk’s birthday, that he’s given a pair of antique glasses, that he comes home to an empty apartment, that he’s embroiled in a rescue of a machine that literally makes newness from death, that he’s surrounded on this mission by a crew less than half his age, that he’s visited by the loose cannon result of his own mistakes… the movie is so single minded in this rollout of themes in its first fifteen minutes that the rest of the plot is infused and illuminated in ways that help it transcend mere adventure. At the risk of Khan-like grandiosity, this movie is universal. (And paramount, if you don’t mind the feeble joke.)

LikeLike

Well, for that paramount joke, Rob, I’m going to have to maroon you on Ceti Alpha 5, I’m afraid. Other than that, great comments. I can neither disprove, nor want to, your theories on the Beach Boys/Beatles influence rolling from Raiders to this to Jedi, although I’d also point to the way that this film accepts a principle that is obvious in movies and yet which television, up until relatively recently, has generally resisted: you have to break up structures and threaten neat arrangements of character and situation. Most TV shows come back to the same situation week after week for the sake of sustaining working dynamics, budgetary concerns, fan followings, etc, whereas movies have two hours to send people on rollercoaster rides of emotion and experience. The Spielberg-Lucas template for their swashbucklers was, of course, entirely predicated upon that sensibility. I think the Star Trek series of films were faced with a challenge, which they met with a surprising amount of success, to strike a balance of these two templates after the discursiveness of the first film, as it kept purposefully demolishing its institutions – killing Spock, blowing up the Enterprise, sending the crew back in time, making peace with the Klingons – but at the same time sustained deeper essentials, like the unshakeable camaraderie of the crew.

BTW, can you link me that podcast? I’d like to hear it.

LikeLike

For a second there, when I saw the photo of Leonard Nimoy, I thought it was of Rosalind Russell in AUNTIE MAME — specifically that bit when she’s getting ready to talk to Fred Clark. And the set around Nimoy *is* not unlike Beekman Place …

LikeLike

Yours is a wicked mind, Chris…

Myself, I’m very fond of the break-dancing Spock contained herein, perhaps a rough draft for the proposed Star Trek II: Electric Boogaloo that sadly never made it out of the development phase:

LikeLike