.

.

Director: Tim Burton

Screenwriters: Scott Alexander, Larry Karaszewski

By Roderick Heath

The career of Edward D. Wood Jnr. went thus: he made bad movies, was not rewarded for this, and died young, poor, weird, and obscure. A simple narrative, one obeying seemingly cast-iron rules of art and industry, a ready example of an almost natural law at work—except that we sometimes tend to rebel against such obvious arcs, a temptation that’s especially strong today when movies can cost $200 million and still be less coherent, personal, or fun than the films Wood slapped together on rock-bottom budgets. Wood’s status as a hero of cash-strapped delirium has passed through phases, from roots in the punk era’s camp-hued affection for trashy antitheses to the slick emptiness of much popular culture, through to genuine, if sometimes over-earnest, attempts to embrace him as the essence of the outsider artist and a ramshackle surrealist.

.

.

In fact, Wood was a schismatic creature, at once a filmmaker who packed his movies with peccadilloes and private delights, and a hack who tried to winnow his way into Hollywood with his own ineffably clueless takes on material he thought popular. Wood lamely attempted to ape his betters, but also was a secret rebel twisting their noses with his characterful statements in favour of acceptance and against nuclear-age blustering, reflecting a general inability to fit into the conformist world of the 1950s, as if he was a prototypical, half-unwilling beatnik lost in a jungle of coldly commercial professionalism. Yet, it was precisely his inability to recreate the art that pleased him and to express his serious ideas in a serious manner that makes his work so disturbingly thrilling at times, the simultaneous horror and delight in the obviousness of the intention and the depth of failure. Edward D. Wood Jnr. has become the Charlie Brown of cinema icons, locked in an eternal frieze, trying to kick that cultural football and missing.

.

.

Tim Burton’s Ed Wood, spun from a screenplay by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, is as much a film about the art and the idea of Wood and what they meant and could mean for other artists and filmmakers, as it is a traditional biopic. Ed Wood views his life through a prism of decades of semi-underground art movements, to celebrate those movements and their clique-happy enthusiasm. Burton feted Wood’s career through a series of ironic contrasts, reproducing his tacky special effects and cardboard motifs with large-budget, detail-driven zest and exacting technical competence, precisely the qualities Wood so badly lacked. Mimicking Wood’s style in the visuals of the film freed Burton somewhat from having to devote too much time to depicting the products of Ed’s work. Burton seemed to latch onto Wood as a personal avatar, another natural outsider, a singular oddball with a strange power for attracting and employing a posse of glorious misfits to whom he could offer a protective wing. Burton also found the same essential pleasure in cinema as a way of exploring the ephemera of things readily dismissed as tacky and corny, and yet which lingered with strange intensity from the shoals of childhood memory and adolescent fixation.

.

.

Wood’s story, at least the notable phase of it depicted in the film extending from 1953’s hallucinatory Glen or Glenda? through to his sci-fi anti-epic Plan Nine From Outer Space (1959), offered plentiful raw materials for a tragicomedy. The film concerns itself mostly with Wood’s friendship with the aging, haggard Béla Lugosi (Martin Landau) and others inhabiting the Hollywood fringe, including TV psychic Criswell (Jeffrey Jones), monster movie hostess Maila “Vampira” Nurmi (Lisa Marie), temporary fiancé and future tunesmith Dolores Fuller (Sarah Jessica Parker), gloriously gay socialite Lyle “Bunny” Breckenridge (Bill Murray), and hulking pro wrestler Tor Johnson (George Steele)–a gallery of characters to rival the Addams Family for incongruous charm and the Keystone Kops for incompetence in the line of duty. Ed Wood is unusual as a movie narrative in many ways, then, because unlike most films, especially biopics, which lead us towards either a singular triumph or cathartic collapse, it becomes instead a snapshot of people fending off the ravages of time with fellowship, and the only triumph is an illusory one. Wood’s employment of the footage he took of Lugosi in Plan Nine is, here, no longer merely a man using a desperate gimmick for box office appeal, but an instinctive poet’s attempt to stave off mortality’s victory and the inevitable dissolution of the weirdly beautiful world he’s built around himself.

.

.

By presenting a biography of a director where the resulting work is, implicitly, negligible, Burton offers one of the most beguiling portraits of the artist as young self-deluder ever. Johnny Depp’s Wood is a creature of manic-depressive highs and lows, sometimes gnawed at by self-doubt suppressed with alcohol, but often skating along on the back of enthusiasm, process, and the druglike rush of believing in his own brilliance. Burton captures the latter attitude in a perfect visualisation: stock-footage explosions and patriotic parades are superimposed over Wood’s beaming face as he marvels at his own achievement, blending both the man’s defining traits and his techniques into a seamless, singular image. Ed Wood is the essence of every artist who has remained convinced of their own worth even whilst every force in the universe seems to be contradicting them.

.

.

For Burton, Ed Wood was a departure, and it remains a stand-out in his career, not only as his best film to date, but also in how he tackled a true story and transmuted it into both companion piece and negative image to his other works, executed with an uncommon economy, yet still stuffed with stylistic coups. Coming after his uneasy rise to the higher ranks of Hollywood through his Batman films, and his still-beloved diptych of black-comedy satires on family and suburbia, Beetlejuice (1987) and Edward Scissorhands (1990), Burton indulged a measure of self-analysis, possibly casting his thoughts back to his own brief partnership with Vincent Price on Edward Scissorhands in regarding Wood’s and Lugosi’s alliance, and extrapolating the image of himself as a man locked in a contradictory posture of eccentric, individualistic creativity finding a niche in a world with opposing priorities and values. Leading man Depp’s interpretation of Wood seems partly channelled through his one-time director John Waters, whose Cry Baby (1990) helped give Depp his first move beyond the teen stardom of “21 Jump Street.” (Waters’ own early efforts were something like Wood’s, though operating from a perspective of self-aware absurdist chic). In spite of the overt artifice Burton indulges, like black-and-white photography and flourishes of generic parody, and indeed largely because of this, Ed Wood is also a film with a sense of time and place so vivid you can practically smell the shady bars, two-room apartments, seedy low-rent studios, and bunkerlike offices of fly-by-night producers. This milieu is inseparable from Wood’s own work, with its location filming in deepest San Fernando and the down-market corners of Los Angeles. Ed Wood captures that atmosphere with an intensity that’s at once tactile, seamy, nostalgically affectionate, and occasionally, as in the opening, transformed into an adjunct of Wood’s shoestring-Expressionist worldview. Ed Wood remains a daydream about the underside of ’50s Hollywood.

.

.

Ed Wood commences with Criswell warning the audience in the manner of his introduction for Wood’s Revenge of the Dead (1960), from a coffin in the Old Willows Place of Bride of the Monster, about the dread experience the audience is about to witness, before the opening credits explore the environs of Wood’s iconography via an extended piece of brilliant model-work, resolving on a soaring vision of Los Angeles transformed into a Gothic wonderland. Wood is found fretting over the lack of press turning up for the premiere of a play he’s putting on. The glimpses we see of the play offer the Wood sensibility already fully formed: a giddy mix of the naively poetic and the woodenly terrible. Wood’s fearsome optimism proves resilient even in the face of a bad review served up by a leading critic’s copy boy, though his fiancé Dolores mournfully takes to heart its jabs at her (“Do I really have a face like a horse?”). Ed’s fairy godmother Bunny cynically dismisses the whole thing with his knowledge of the forces that really run Hollywood: sex, power, and money.

.

.

Ed, whose day job is carting around props at Universal Studios, is a man constantly trying to understand the business he’s involved in, marvelling at the forces which can produce camels for a bit of backlot flimflam, and yet its resources of magic remain ever out of reach, even as he finds possibility and excitement in detritus like the reels of stock footage an older employee digs out and then files away. Wood’s adoration for and grasp on the potential in the marginalia of this world extends to his spotting of Lugosi, whom he happens upon as the aging, haggard star is checking out coffins at an undertaker’s for the next exhausting tour of a production of Dracula, hanging onto the last vestige of his fame and means of making a living. Ed makes friends with Lugosi simply by offering him a ride in his car, saving the once wealthy star from having to catch the bus.

.

.

Ed’s tale is as much about trying to subsist and thrive within the precepts of the grand narrative of American and Hollywood success, whilst also, almost accidentally, trying to resist the pulverising conformity those 1950s narratives could assert, as it is about making bad movies. Late in the film, Ed and future wife Kathy (Patricia Arquette) reminisce over their childhood love of the figures of wonderment broadcast to them through the highways of pop culture, from pulp radio serials to Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre, evoking the way such enchantments change lives even in the boondocks. Ed’s attempts to get into that game himself retain this innocent quality. Ed’s troupe become something akin to a family, accumulating members, some gleeful, some resistant, but all glad to find a temporary shelter and the shreds of dignity Ed’s drive gives them. Lugosi entrances Ed with a nostalgic, pseudo-intellectual paean to delights of the classic Gothic horror film, complete with Freudian jive about the felicities of Dracula as spur to scoring with the ladies in a humorous tilt that seems aimed as much at the psycho-sexual desolation of most contemporary genre film as at the ’50s giant monster craze Lugosi derides, as well as the spectacle of two horror nuts trying to lend their obsessions a veneer of profundity. (No, I wouldn’t know anything about that.) Mostly, it establishes Ed and Lugosi as men fundamentally out of step with their technocratic and fashionable time, one in which Lugosi is grievously humiliated on a live TV comedy show where the host’s improv mockery overwhelms Lugosi. The sequence suggests the real way Lugosi had been reduced to a comic foil in Abbot and Costello and Bowery Boys movies. Ed can’t even get Dolores to dredge up Lugosi’s name in making her guess who he just met (“You met — Basil Rathbone!”).

.

.

But Ed, in finding himself a star who needs money, gains through Lugosi a ticket into the great world of movie directing, even if it’s only a film about sex changes, hastily redrawn from a Christine Jorgensen biopic after the rights get too expensive for producer George “I make crap” Weiss (Mike Starr). Ed, after catching the article about Weiss’ efforts in Variety, makes his initial pitch to the bewildered producer, trying to compel him with his own secret kink, his love of cross-dressing (“You a fruit?” “Oh no, I’m all man. I even fought in WW2”). He manages to draw the beefy, volcanic Weiss in with eager interest with tales about making parachute landings in the war whilst wearing a bra and panties. Ed’s desire to be a success is constantly stymied by, and also inseparable from, his desire to present himself unmasked to the world, and to explore himself and his obsessions through his work, lacking the essential inner censor who can corral such impulses into professional limits. Late in the film, he convinces Baptist Church stalwarts Reynolds (Clive Rosengren) and Reverend Lemon (G.D. Spradlin) to give him the money to make Plan Nine from Outer Space, or Grave Robbers from Outer Space as it’s initially called, promising to make them enough cash to bankroll their own pet project, a series on the 12 apostles, only for the uptight religious financiers to take umbrage at Ed’s habit of putting on the angora sweater and blonde wig to relax on set.

.

.

One comic highlight here is the striptease Ed does for the for Bride of the Atom wrap party, with Criswell slipping cash into his garter and concluding with Ed unveiling to display his beaming, dentureless face in a moment of pure camp-grotesque cool. Fittingly, it’s both the moment of Ed’s personal liberation and the final straw for Dolores, who announces she’s leaving him to write songs for Elvis Presley. Ed’s personal identification with Orson Welles (Vincent D’Onofrio and Maurice LaMarche) as the symbol of youthful, all-encompassing genius presents the hope of the artist-rebel as transcendent titan, as opposed to Wood, doomed to be the image of the artist-rebel as ant. The climactic (fictional, but readily imaginable) encounter of Welles and Wood spells out the similarities in their career troubles and dreams in sarcastic, and yet oddly accurate terms. For artists, Ed Wood constantly suggests, the only hope for such contrary personalities is to try to reconceive the world through the personal prisms of creativity, making no distinction between good and bad artists. Wood’s attempts to do so culminate when he uses his draft screenplay to reveal his predilection to Dolores, his doting partner rising in realisation from the chair in their kitchen to open the door upon Ed in full drag, like a sweet-tempered Frankenstein’s Monster.

.

.

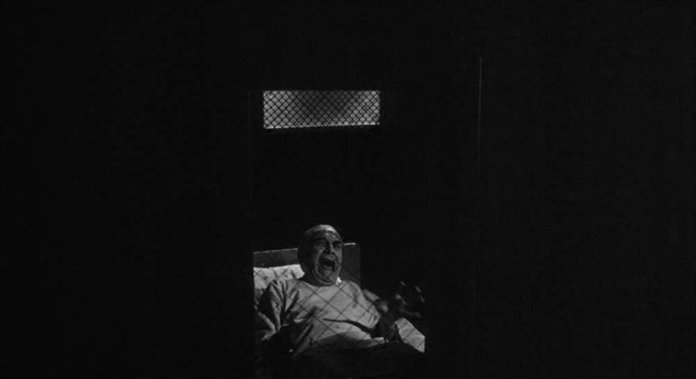

Whilst art is liberating in Ed Wood, it is also enslaving. Lugosi finally, happily embraces association with a single role to the extent of having himself buried in Dracula’s cape, a fate many actors would recoil from precisely because it’s the last chance to force reality to obey their own will. Lugosi, in readily adopting his Dracula guise, is photographed taking his fixes in shadows, as if he’s become one of his own expressionist grotesques, and is finally found lolling in a pool of despair and self-pity; composer Howard Shore uses strains of Swan Lake, the theme of crepuscular romanticism from Tod Browning’s film, to lend undertones of tragedy to Lugosi’s attempts to hold onto his final alternate identity. The generally jokey movie quotes segue into outright horror, in the glimpse of Lugosi tied up in rehab, screaming at detox horrors, a vision transmuted through a B-movie nightmare. In counterpoint to Ed’s awkward emergence as the man he really is comes a transformation of Dolores herself, one which Parker exposits in a key of cleverly stylised archness. Dolores moves through stages of twentieth century American femininity, souring slowly from the ever-chipper, supportive wife-to-be, to a domestic terrorist who knocks Ed with a frypan brandished in Amazonian ferocity, as well as a wisecracking professional who leaves Ed in a mixed fury of personal and professional frustration. Ed offers movie stardom to Tor Johnson, who believes he’s “not good-looking enough” to be one: “I believe you’re quite handsome,” Ed assures him. He gives the girl just off the bus, Loretta King (Juliet Landau), a chance to become a star, too, even if it’s only because he mistakes her for a rich kid who can invest in his movie, and the act of trying to capitalise on this results in the start of the breakdown of his relationship with Dolores.

.

.

The secret codes of show business remain, however, constantly undecipherable to the wonderstruck Ed, even as Criswell tries to clue him in: “People believe my folderol because I wear a black tuxedo.” The spectacular failure of Glen or Glenda? leaves Weiss threatening to kill Wood if he ever sees him again, and Universal Studio exec Feldman (Stanley Desantis) thinks it’s a practical joke foisted on him by William Wellman, before declaring to Ed that it’s the worst movie he’s ever seen. “Well, my next one’ll be better!” our hero replies without missing a beat, only to meet dial tone. Still, Ed tries to make the movie he thought up on the spur of the moment when talking with Feldman, Bride of the Atom, both for his own sake and for Lugosi’s, as the actor becomes increasingly distraught over his lack of money and doubtful future. This time, Ed attempts to raise funds independently, cueing a series of excruciatingly funny attempts to fool rich people into giving him money. Ed reaches an abyss of humiliation after a chance encounter with Vampira leaves him begging on his knees, looking like the biggest schmuck in history. Vampira herself describes the same downward arc as the others, only quicker, for when the moment of success is exhausted, she’s reduced to travelling on the bus in full arch-brow, décolletage-flashing Goth garb on the way to a job for Ed, unaware of how she provides a barren stretch of L.A. with a sketch of surrealist delight. “You should feel lucky,” Kathy admonishes her when she’s mournful about sinking to appearing in one of Ed’s film,: “Eddie’s the only fella in town who doesn’t cast judgement on people.” “That’s right,” Ed adds, “If I did, I wouldn’t have any friends.’

.

.

Ed Wood is first and foremost a comedy, and indeed it is, to me at least, one of the most truly, consistently funny films ever made. Alexander and Karaszewski’s dialogue is absurdly quotable—back in the late ’90s when I was often trying to shoot no-budget, hand-crafted movies with family and friends, every new shot was presaged by our own ritual quote, “Let’s shoot this fucker!”—and the film is littered with tiny bits of comic business that provide endless pleasure. Much of the humour resembles those little sketches in the margins in MAD Magazine, captured in throwaway flourishes of wit, far too many of them are worth mentioning but impossible to cram in here. Wood’s labours, from running from police because he lacks a filming permit to breaking into a studio warehouse to steal a giant octopus prop, inhabit the realm of farce.

.

.

Burton leavens it all with his most precise comedic rhythm and staging. There’s strange magic in Ed setting his impish helpmates and actors Paul Marco (Max Casella) and Conrad Brooks (Brent Hinkley) to find props and dig up body doubles for the deceased Lugosi, scurrying into action like lost members of the Three Stooges; in Ed and Lugosi watching Vampira on the TV presenting White Zombie (1932), with Ed irked by her sarcasm whilst Lugosi marvels over her jugs, attempting to hypnotise her through the TV screen; in Bunny submitting to a baptism for the sake of getting financing for Plan Nine, Baptist beatitude and nelly enthusiasm finding a bizarrely beautiful accord; and in stealing the octopus for Bride of the Atom, a moment in which Tor takes on the persona of Lobo to wrench away the lock on the warehouse door. The film’s set-piece comedy sequence, one of the funniest scenes in anything, revolves around the disastrous trip Ed and his troupe make to attend a premiere of the retitled Bride of the Monster, only to find the crowd going berserk, an event that sees them mugged by lecherous adolescents, lost in a maelstrom of popcorn (“I gotta save ‘em!”), and chased down the street by rioting movie fans, after the hearse they arrived in is found being stripped down by street hoods. For a moment, all the boundaries between persona and person, movie and reality, dream and discontent dissolve in a frenzy of anarchic delight.

.

.

For Burton, Ed Wood’s formal rigour, as well as the concision of its humane yet raucous spirit, remains unsurpassed. The lucid, often bald and unflattering, and yet also often textured, swooning beauty of the Stefan Czapsky’s photography is one of the film’s great qualities. Burton and Czapsky find actual expressionism lurking behind Wood’s half-assed attempt to find it in his jerry-built sets and location shoots. They transform the interior of Lugosi’s shell-like prefab house into a Gothic castle littered with remnants of former greatness and Lugosi’s past—the beauty, mystery, and threat of the exotic imprisoned in suburbia. Burton actually extends the dualistic contrast of Wood and Welles by constantly using Wellesian technique to depict Wood’s world, with soaring camera surveys of models that seems liberated from physical limits, passing through glass, in and out of water, with the sort of joie de vivre Wood himself seemed to be chasing haplessly; deep-focus, multiplaned shots and deadpan, medium-long shots, sometimes engaging in dramatic spoof or comedic contrast, and just as often leaving his characters stranded in their hapless pathos. Such dazzling cinema is often the very opposite of what Wood was infamous for, and yet his own flourishes of oddly inspired low-rent hype, like the lightning strike that announces his own name at the start of Plan Nine from Outer Space, are faithfully reproduced. One of my favourite shots in the film comes when Lugosi gives an impromptu recital of his famed “Home? I have no home” speech from Bride of the Monster, with Burton’s camera shifting to frame Lugosi under a building façade that provides him with a suitably sepulchral proscenium arch. Equally terrific is Shore’s scoring, one part satire on the tinny stock music slapped onto Wood’s films, one part celebration of retro weirdness, complete with theremin whistling eerily over driving beatnik bongos.

.

.

Many biopics tend to reduce their subjects, and that’s true to a certain extent here. Ed’s sideline as an equally terrible screenwriter for hire is left out, and Lugosi, who had an entire politically tinged history in Hungary, is a touch less than the commanding figure he was. But considering the film’s theme of how show business turns everyone, for better or worse, into the image they create for themselves, such diminution is understandable. Suffice to say Landau’s performance deserved every one of his copious plaudits, and the rest of the cast is impeccable. For Depp, though the film gained him little real reward at the time, it remains one of his best, most cleverly pitched performances, one that proved he could move into adult roles and introduced him as that most contradictory of figures, a star character actor. The film’s powerful undercurrents of melancholia, even tragedy, as it encompasses Lugosi’s sad final months and the start of Wood’s alcoholism, does not overwhelm the comedy, and in some ways even enhances it. Landau’s professed ambition to make Lugosi both funny and sad describes the film as a whole, as both emotions here well out of the same fundamental details—the try-hard aping of mass commercial culture, the struggle to retain a sense of personal beauty in the face of impersonal forces, the ravages of age and the hopeless delusion of youth. It’s a note that becomes especially keen in the closing moments when Kathy and Ed leave an imaginary triumphal premiere for Plan Nine to get married in Las Vegas. Ed’s real story was doomed to run out of gas somewhere out there in the California desert he and Kathy are last seen heading off into, but his legacy remains. The roll call of the characters’ fates listed in the prologue rams home the ephemeral nature of their labours, even though time has proven kinder to so many of them than they might have expected. The true cheat of Ed Wood’s life was his death barely months before his rediscovery commenced.

I can’t resist doing one quote:

Edward D. Wood, Jr.: [after Tor Johnson bumps into a scenery wall while walking through a door making the wall shudder] Ok, and CUT! PERFECT! PRINT IT!

Cameraman Bill: Don’t you wanna do another take Ed? Seems like big baldy had some problems gettin’ through that door.

Edward D. Wood, Jr.: No, it’s fine. It’s real. You know, in actuality, Lobo would have to struggle with this problem every day.

Ed was an American neo-realist.

LikeLike

I still think was the best work of both Tim Burton and Johnny Depp’s careers. I’m never not entertained by it.

LikeLike

Syd: “Ed was an American neo-realist.”

Ha! And of course Glen or Glenda? is quintessential neo-realism in some respects.

Dave: Oh yes. For Burton, squarely, although Batman Returns and Sleepy Hollow are within striking distance for me.

LikeLike

The ignored prophet, visionary or misunderstood genius who perseveres until vindicated is a cultural staple. We tend to hear less about the deluded, the wrong and those who fall just short. It would be easy to describe Ed Wood is the antithesis of this heroic archetype, but he demonstrated the self-belief and determination to overcome numerous obstacles to become a filmmaker; it was just that his vision was not worth realising. His work barely aspired to be kitsch, its achievement was existing at all.

Ed Wood has become an exemplar of earnest, but empty endeavour. Similarly, his films are a representative nadir of cheap fifties alien invasion and monster films. Arguably, if his work had been marginally better, he would have remained anonymous outside geekdom and the occasional film study dissertation. It is somewhat ironic that he has achieved unfathomable fame as cultural marker.

Ed Wood is speck of dust about which a snowflake formed

LikeLike

Well said, J-man.

LikeLike

Good review. This is probably my favorite piece of work that Burton has done and still consider it one of Depp’s best performances of all-time. Shame that Burton hasn’t been able to capture a warm-hearted satire like this in awhile but at least he made us remember who Ed Wood was once again.

LikeLike

A very good review that reminds me of what Burton and Depp are capable of. It is interesting that my favorite Tim Burton films are Batman Returns, Ed Wood, Mars Attacks and Sleepy Hollow, which were made one after the other. His movies since then have undoubtedly been more successful, but he always seemed to be trying too hard. Yep, Ed Wood was a work of brilliance.

LikeLike

Well, Andrew, my own complex feelings about Burton’s recent career were spelt out at length in my Dark Shadows review a few weeks ago, so I won’t repeat them, but I will certainly agree the man was on a roll at that time.

LikeLike