.

.

Director: Walter Salles

By Roderick Heath

Jack Kerouac’s novel On The Road, published in 1957, bears a weight of cultural resonance that few modern texts can claim. Kerouac’s freewheeling ode to being young, energetic, irresponsible, and constantly on the hunt for new dimensions of experience brought the Beat clique’s artistic sensibility to a wide public consciousness, or at least one that didn’t involve obscenity trials, and helped animate the fantasies of footloose youth amidst successive generations. Kerouac had strived to create a specific kind of art, based in a celebration of movement and the moment, an artefact that resisted analytical introspection, but which also tried to turn reportage into a quest tale, that’s part Arthurian Grail saga, part John Bunyan-esque pilgrim’s tale, and part Walt Whitman-derived national poem. It’s a novel commonly, easily reduced to a basic celebration of a particular feeling and a rite of passage, a founding myth for modern youth culture. Many of the criticisms levelled at Kerouac’s writing are accurate, and yet few ever contend with the actual point of his labours, a point that was sharply at odds with the increasingly pompous, intellectualised state of the literary novel and its arbiters, which was to reject, or at least reconstruct, familiar literary values and try to drag the novel back to a state of experiential transmission: in an art form best known for its appeal to the introspective, he wrote about the specific thrill of doing stuff – dancing, driving, necking, jesting, raving on – as well as any writer ever has. Filming Kerouac’s novel had proved an elusive goal ever since. Transforming the “ragged and ecstatic joy of pure being”, as Kerouac described it, into artifice was the singular success of his labours, and trying to retransmit that as the recreated collection of sounds and images called a film, is doubly perverse.

.

.

A peculiar form of nostalgia possibly inflects the way the book is perceived now, as a wistful look back over the shoulder to when bohemian life and artistic expression weren’t bound up with pseud posturing, referential awareness, and politically correct touchiness, let alone the intervening age of reactionary schism that has toned the American social landscape, as Kerouac’s efforts to describe the openness and communality he encountered feels now more like the calm before the storm. By the time Easy Rider (1969), cinema’s fittest analogue to Kerouac’s novel, came along, the adventure ends with tragic, bigoted murder, and nobody doubted its plausibility. Kerouac, for his part, was trying to cast off cultural deadweight too, the staleness of pre-war politics, the immediate hangover of the militarisation of Western society, and the oncoming age of corporate-consumerist triumphalism. Perhaps for this reason, Kerouac’s message, and his method, could be therefore newly relevant; Kerouac’s attitude of aestheticized reportage lies behind a vast swathe of contemporary cinema. Brazilian director Walter Salles comes to the material after The Motorcycle Diaries (2004) similarly turned Che Guevara’s youthful peregrinations into a study in transformative revelation for the future revolutionary. In that film, Salles, to the irritation of some, avoided polemics and overt constructions of context, in favour of descriptive acuity, preferring to allow the meaning, or indeed the ambiguity, of situations speak for themselves. Guevara’s trip was one of growing radicalisation, something Salles described as based in direct encounters with the world, but he also allowed room for observations of the sorts of forces that would contradict and finally defeat Guevara’s efforts. Salles takes a similar approach to On The Road, avoiding commentaries on the Beat scene and its meaning to inheritors, instead offering it as a series of unvarnished personal observations that amass into not so much a narrative as a description of a life phase, and a journey of necessary growth for an artist.

.

.

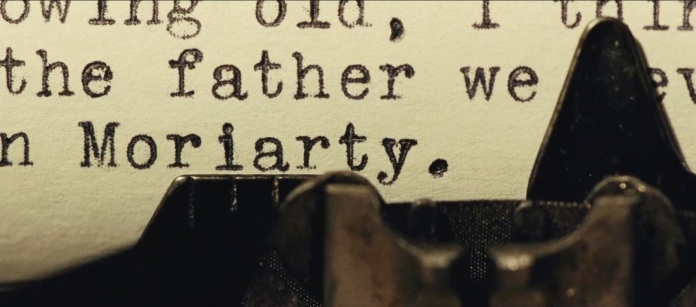

Salles’ film can be described as a tonal betrayal of Kerouac’s book, in order to get at its own sense of the book’s truth. Where the novel is feverishly ebullient in its descriptions and expression, and the faiths it expresses overtly and implicitly, Salles and screenwriter Jose Rivera are more restrained and, in a deadpan fashion, ironic and interrogative. They peer into Kerouac’s blind spots and finger the sore spots he placed Band-Aids over. The script was based not on the finished, polished novel but on the famous “scroll” draft that Kerouac pounded out on sheets of paper taped together, so as to let his tale flow out and recreate artistically the immediacy of the events he inscribed. The tone is closer to being an overt portrait of the real-life figures Kerouac was writing of, including himself, with Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund) less the gorgeous holy fool he is in the novel than the bad lot his model, Neal Cassady, could often be. This brings it closer in tone to an established, still proliferating body of film works looking at the Beats, including Heart Beat (1980), Naked Lunch (1990), The Last Time I Committed Suicide (1997), and Howl (2011). Some of these are fine, others are actively terrible: I still shudder when I recall the cut-rate 2000 film Beat, which starred Courtney Love as Joan Burroughs, uttering the line, “I’m staring into the abyss.” The cultish quality of Beat has often been its own worst enemy. Salles’ approach avoids that sort of thing, and also the hallucinogenic illustration of Cronenberg on Naked Lunch.

.

.

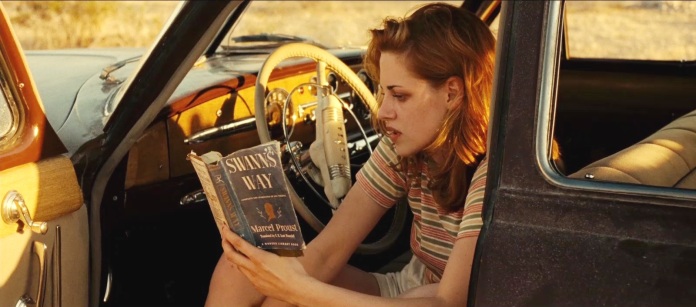

Unlike in the finished novel, this version commences not with Kerouac avatar Sal Paradise (Sam Riley) having just been divorced, but just after his father died: Sal of the novel is a more mature figure, more sexually and socially formed, than the one we get here. Salles and Rivera suggest squarely that the accord between Sal and Dean is, thusly, rooted firmly in their mutual search for a missing father figure, a father figure lost somewhere amidst, and perhaps indivisible from, the land around them. Dean’s father is a vagrant he’s long lost track of, only believing he’s somewhere around his home town of Denver, Colorado. Dean was born to the kind of rootless, perpetually yearning, fragmented lifestyle that Sal and his pals lean towards by choice and desire. Sal, a blocked young scribe hovering fretfully over his typewriter with nothing to say, is introduced to Dean when he blows into New York by Chad King (Patrick John Costello), mutual friend of Sal and poet pal Carlo Marx (Tom Sturridge), analogue for Allen Ginsberg. Carlo is quickly besotted with Dean, a recalcitrant but charismatic, fearless misfit, and has his first properly sexual affair with the young gadabout, although Dean has recently married teenage lovely Marylou (Kristen Stewart). Sal and Dean strike up a fast and solid friendship based not merely in that hunt for a father, but also in “intellectual” Sal’s desire for the kind of openness to life’s vagaries that Dean seems to wield so fearlessly, and Dean’s aspirations to the kind of artistic, ennobled non-conformist lifestyle that Sal, Carlo, and others in their social circle maintain. Dean soon departs the city, but later invites Sal to come to Denver, where Carlo has already followed him, and he finds that Dean has already divorced Marylou and taken up with the more centred, conservative Camille (Kirsten Dunst). Dean soon flees Denver for some solo adventuring, shacking up with Latino agricultural worker Terry (Sonia Braga) and sharing in her exhausting but simple lifestyle for a time, before returning to New York.

.

.

Salles has a gift for inscribing a sense of time and place in fresh and atmospheric fashion, and capturing behaviour in a way that feels at once acute and happenstance, avoiding the familiar indulgences of a lot Method-inflected improvisatory cinema and also the fussiness of many period films. Salles’ talents in this regard were particularly important to filming a book like this: the recreation of the late ‘40s atmosphere in On The Road is gorgeous, accurate to the argot and the tactile realism of the age without coming across like a bohemian dress-up party. Salles’ visuals, via the brilliant photography of Eric Gautier, capture landscape with a blend of stateliness and veracity. It’s in this regard that Salles’ film is most successful, his evocation of a grittier, fresher American landscape that’s been colonised by humans who share a language and a sensibility, but not yet invaded by mass market culture, a place where both joyous fellowship and dwarfing solitude, plenty and desolation are all easy to find. The opening sequence is a particular beauty, an in media res introduction that finds Sal stalking a lonely highway before explaining how he got to be there: he’s picked up by a truck carrying some other itinerants, and they share cigarettes, liquor, and ragged singing in the dull gloom of a dawn filled with outsized wonder and mystery.

.

.

The bulk of the film is filled with moments of such beauty, the unexpected grandeur of dawn over a strange mountain range, the mystical lustre of a fog, the bleary beatitude of the distant New York horizon as Sal returns to the fold, raw desert, bleak snows, the outskirts of a town you’re leaving – familiar for any attentive traveller and conveying the world Kerouac tried to capture. A film of the novel, rather than another straight biography of the Beat heroes, could, arguably, properly look like what Antonioni managed with Zabriskie Point (1970), or the best moments of Easy Rider or Alice’s Restaurant (1969), perhaps even, in the depressive counterbalance to Kerouac’s mania, the likes of Two-Lane Blacktop (1972) or The Brown Bunny (2003). If Oliver Stone or Francis Coppola – who was going to make the movie at one point and served as executive producer – had made this, in all likelihood they would have reproduced on an audio-visual level the indulgence of the characters and their world views, where Salles is more sceptical, evoking these elements without abandoning observational realism.

.

.

Kerouac certainly wrote prose, a living, rambling creature drunk of pure sensatory overload in the American landscape, as a way of communicating the crypto-spiritualism of Kerouac’s sensibility, and yet On The Road is really more a kind of lyric poem that flows with words like a swollen river. The necessity of this is that without it, Kerouac’s tale can be taken for one of mere youthful hijinks. Salles’ approach is more literal and less encompassing, and his poeticism prefers to find constant minatory epiphanies, from the dull glow of a last cigarette smoked on a desolate morning to the fog wreathing the temple-like pillars of the Golden Gate Bridge, and the weird blend of alienation and fellowship glimpsed when a young cowboy hitchhiker sings a mournful ballad, listened to with melancholy fascination by his hosts. Lyrics of hellfire and damnation accord quietly with the bubbling unease and neurosis that lies beneath the fracturing threesome’s jaunty exterior, as Marylou contemplates the oncoming end of the journey and her affair with Dean, and Sal studies her simultaneous youthful promise and sphinx-like self-containment.

.

.

Salles and Rivera contour Kerouac’s mystical pretences into the drama and visuals, depicting these young men’s journey as a tightrope dance between saintliness and damnation in their search for transcendent states of being. The filmmakers also contend objectively with it, offering up Kerouac’s avatar for William Burroughs, “Old Bull” Lee (Viggo Mortensen), as a corrective who probes Sal’s description of Dean. Where Sal sees him as a kind of Benzedrine-imbibing St Francis, Lee writes him off as a selfish sociopath: “So he’s a holy man now, a religious figure in your eyes?” Lee asks with disdain. It’s a strange film indeed that offers up William Burroughs as the voice of wisdom, although Salles tempers it by having Lee describe Dean as potentially violent and then resume his own hair-raising habit of blasting away at bottles with a handgun in between sentences. He also shows off one of his pseudo-inventions, really a piece of installation art, which supposedly cleans out cancer-causing agents in his body.

.

.

Meanwhile Lee’s wife Jane (Amy Adams), frazzled and possibly mildly psychotic, beats at trees trying keep small lizards from climbing all over them and advises Galatea Dunkel (Elizabeth Moss) in the arts of fellatio. The seriocomic concision of this sequence does point to how Salles’ approach draws out an element of the novel which is partly buried underneath the rollicking surfaces of Kerouac’s novel, that it was also a series of situational portraits, depicting his artistic, bohemian, and happenstance friends in islets of individual crises, eccentricities, and striving labours to create a new and better American art and life. And Salles is brilliant in laying bare the dark, manic-depressive, exiled underbelly of the frenetic, rhapsodic side of Kerouac’s writing. The lizards that infest Jane’s trees which she bats at fearsomely emerge as a superlative visualisation at the forces already eating away at the homey settlement of post-war America and enacted by these anti-heroes, wilful guerilla warriors against boredom and time who also represent the Id of the modern age cracking out of a chrome-plated skull.

.

.

And yet Salles evokes the religious core of Kerouac’s perspective ironically through characters like Lee himself: when the voyagers first arrive in Lee’s house, they find their friend sprawled in an armchair, clutching his infant son with his track-mark riddled arm exposed, a blend of Madonna and Jesus icon, a Dostoyevskian figure of beatification found through raw and debasing experience. Kerouac’s novel is plotless, and so is the movie, rightly if not promisingly for many viwers. Whereas with The Motorcycle Diaries there was a “…and now you know the rest of the story” aspect to lend weight to the meandering, here the ultimate goal, beyond Sal’s finally finding his muse, is more opaque, but what emerges is, rather than the youth culture Mahabharata, is a portrait in individual growth. Stripping away the mythos of this material leaves this aspect most crucially exposed: On The Road is not simply about the joys of being immature and yearning, but also about the moments in which youth, or at least the naïve, all-embracing mood of youth, passes and is reconfigured into wisdom, with Dean as one of those great friends you eventually realise isn’t a person you want to be, and eventually you never want to see again, but still the days of freewheeling kicks linger with the patina of a lost Eden. Sal’s evolution, both in the company of his friends and during an adventure alone, is the point if there needs to be one, his passage through his country and discovering it as a place of both cruel realities and raptures.

.

.

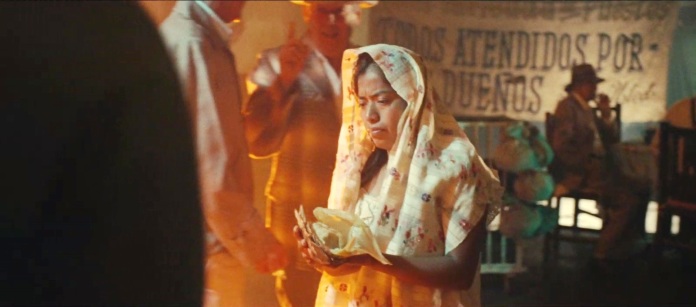

The minutiae, the day to day details of trying to survive such a lifestyle, are perfectly observed, like Sal collecting cigarette butts to make his own, and moving on with scowling impotence when paid a pittance for a day’s labouring. Whilst Rivera trimmed several excursions from the narrative, my favourite passage made the cut, that in which Sal hooks up with Terry and joins her Latino kith and kin as a wandering harvest labourer for a time. This interlude is at once grim, as Sal perceives his own lacks baldly in picking cotton and being introduced to the rude truth of working class life, staring exhaustedly at his pitiful profit for a day working in the sun placed in his damaged hands, and yet also experiencing a rare time of gritty, simple, erotic fecundity with Terry, before they part, Terry grinning to herself in immediate nostalgia for a relationship they both know ends with him returning to New York even as he calls for her to follow him later. The sequence is alive to the transitory beauty and sadness of this brief yet crucial relationship.

.

.

Likewise homosexual elements elided in the book and yet crucial to the Beat scene are given their due. Sturridge’s Carlo, with his airy verbal rhapsodies and charming pretence, captures something of Ginsberg’s talent, charm, and warmth even as he could easily seem like a colossal poseur, going through an extended internal wrestling bout with his psycho-sexual confusion, vowing to go off to Africa and smoke himself into opiated ecstasies and later recounting a failed suicide attempt with good-humoured dejection. Sal and Dean’s friendship is always charged with an element of attraction, culminating in a scene in which Sal is disquieted by catching sight of Dean hustling money by screwing a middle-aged businessman (Steve Buscemi). Hedlund, previously best known to me as the heroic void of Tron Legacy (2010), is surprisingly effective as Dean. Dean’s bold eccentricity manifests upon his first meeting with Carlo and Sal, coming to answer the door stark naked, Marylou lolling in bed in their flat, the fetid atmosphere of sex and booze and poverty belied by the glamorous rawness of the duo. Hedlund’s Dean surveys Carlo and Sal with a wide stare that seems at once open and somehow fathomless, blank, eternally hungry and unfillable. Dean is at once deeply egocentric and rapacious in his drives, qualities that will lead him to eventually hurt those close to him, and also a genuine misfit, anxiously generous, for whom the niceties of everyday life in modern, suburban America are a confounding trial. He also collects interesting people, mostly female, including the innocently, raucously randy Marylou, and the knowingly wicked Rita Bettancourt (Kaniehtiio Horn) who sucks down coffee laced with Benzedrine with a self-administered catechism, “Bless me Father for I will sin,” and whilst she and Dean rut, Carlo’s cries of complaint about the noise inspire Dean to march out and drag him into bed with them.

.

.

Sal and Dean’s relationship, and their mutual, strange one with Marylou deepens when Dean turns up unexpectedly at a house of Sal’s sister’s house where his family has gathered on Thanksgiving, with Dean having dumped Camille and their child off in the hinterland and taken up with Marylou again, in the company of another accidental wanderer, Ed Dunkel (Danny Morgan), whose wife Galatea has turned up at the Lees’ house outside New Orleans trying to locate her wayward spouse. After Dean volunteers to ferry Sal’s francophonic mother (Marie-Ginette Guay) to New York, he then sets out with Sal and Ed to rescue Galatea from the eccentric care of the Lees, rolling on their five-finger-discount way after they’re harassed by a cop who takes exception to these freaks and have to pay a steep fine — a rare moment in which the nettling force of authority descends on these escapees from normality. Sal’s already been invited into bed with Dean and Marylou at her behest, a threesome that stalled thanks to Sal’s self-consciousness that drives Dean irritably from the room, and their simmering mutual attraction and Dean’s determined adventuring manifests most amusingly when, after they’ve managed to divest themselves of the Dunkels and are driving across the Midwest, he has them all strip off and drive with Marylou between the two men, pulling them both off in a scene reminiscent of the mediated pan-sexuality glimpsed in Bertolucci’s 1900 (1977).

.

.

It’s hard to think of a more exact fashion for Stewart to shake off her Twilight-ingenue phase than this scene which amusingly, incidentally, trashes the prim love triangle of her famous franchise. Stewart’s best moment in the film is earlier, however, as Marylou and Dean dance with proto-raver abandon to Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts” to the delight of the New York bohemians, emissaries of liberation. When they turn up at the door of Sal’s sister’s and crash the family gathering, they’re more like envoys from an alien planet. Dean charms his way through dinner and then confesses to Sal of having recently passed through a bout of suicidal despair, having sat alone for hours with a gun trying to work up the will to kill himself. The characters are only half-willingly trapped on the outside, with Marylou surveying even the Lees’ fetid house in search of signs of domestic contentment, and Sal later peering through a department store window, studying televisions like these are the true artefacts of an alien landing.

.

.

Sal and Marylou’s relationship finds fulfilment in one night of ragged passion after Dean essentially dumps them both off so he can continue with Camille and his kid, Marylou chasing him off with a well-worded missive and then retreats to a corner to don her battle gear for a life of survival without him –- blood red lipstick all the better for seductively handling a hotel clerk. Salles repeats this motif after Camille in turn kicks Dean out after he and Sal come back from a night of fun, returning to a suburban house with the pitch of sullen fury mixes with baby screams into a symphony of nerve-shredding, Dean kissing his child goodbye and exiting with sullen grace, whilst Camille takes a long hard look at herself in the mirror and then steels herself in her nurse’s uniform, getting on with the business of living with a child. Salles’ quiet toughness on the sexism of Dean and others of this world is bracing. Galatea Dunkel’s tough, ruthlessly honest, if also priggish and self-important centrist values and unwavering criticality of these wayward lads is beautifully communicated by the ever-excellent Moss in a too-brief appearance. Dean’s hopeless inability to settle is however finally revealed as a pitiable curse rather than a mere convenience. The film’s final passage is majestic, a hallucinatory, Peckinpah-esque depiction of the pair’s final trip, a drive into Mexico where the pair finally find the orgiastic, consciousness-drowning experience – an indulgence of the carnal so immediate it liberates the spirit in a moment of rhapsodic lunacy – which they’ve hunted high and low for.

.

.

The duo meet up with young scallywag Victor (Joel Figueroa) hungry for US currency, with whom they share a joint the size of a stick of dynamite, before he leads them to a whorehouse where they find eruptive release, Dean shaking from stem to crown like a whirling dervish in communion with godheads as he fucks and vibrates to jazz. So exciting are these carnal cavaliers that the whores and their town farewell them as they continue to Mexico City, where a romp through the streets at night, passing through the very gut of a teeming organism of human life, becomes another dance between devils and enlightenment, Salles’ lenses highlighting Madonna statues and skull-masked children dancing around the duo. This is prelude to Sal falling desperately ill, lying sweating and tortured by visions of his lost friends, and finally abandoned by Dean who leaves him to recover whilst continuing to chase whatever the hell it is he’s after. Sal and Dean’s last encounter on a frigid New York street with Sal heading off for a concert sees Dean appearing out the darkness, at last fully transformed into the frazzled, glowing-eyed, hollowed-out demon-beset saint Sal had always suspected he was, begging Sal silently for forgiveness whilst bearing the marks of damage that his continued journey left him with, as if Sal in fact got off easy whilst Dean’s continuing the quest took him to a bleak and ecstatic place that left him with no future, only more road.

.

.

Sal soon after finally begins creating the work we’ve been watching, creating the scroll draft in an explosion of creative self-exorcism that leaves off with Dean’s name repeated like a catechism, their search for unfound fathers still haunting them and Dean now a roaming spirit somewhere in the west, transmuted by Sal’s imagination into the personification of all things strange and off-kilter in an America starting to worship the television and the washing machine. Riley, after his wobbly work in Brighton Rock (2011), returns to best form in playing Sal, who is always two people, the fawnish young romantic on screen and the croaky narrator whose experience is written in his vocal chords whilst his face transforms as the film unfolds until he’s lined and hairy and the hurt as well as blessings of his life on the road pools in his eyes. Like Omar Sharif in Doctor Zhivago (1965), he’s the dreamy but increasingly battle-scarred conduit for the drama as much as protagonist.

.

.

On The Road doesn’t always sustain the intensity of Kerouac’s writing or its own best passages, and on some levels I can understand the problems some have with it: rather than a tale of great moment, this is a grace note, a recreation of time past that asks less, what can be, but rather, what happened? Rather then presenting a road map for modern hipsters, the final thesis of the film suggests that for all the philosophy and life hunger Kerouac tried to present, he also succeeded in painting a portrait of people permanently cut off from their world and their moment, aliens in their own society, no matter how many funky kids tried to emulate their example. But it’s this slightly bitter realism, the acute reflection of the dark and downside of life in bohemia in any era as well as its ephemeral joys, that I liked. And the film is, especially in its concluding passages, true to the Roman candle vividness and floundering yet desirous spirit of Kerouac’s work, a rich and marvel-studded misfire, whilst resisting being another classic illustrated, a demystification that finds raw humanity under the sainted prose.

Well said! I enjoyed this film much more than I thought I would. There were so many ways Salles and co. couldn’t screwed things up and for the most part they got it right. I feel that he accurately captured the spirit of the novel and the intense feelings that the characters had towards each other and life in general. Kerouac and co. were all about enjoying and embracing the here and the now and this was embodied more than anyone else in Dean. I felt that the film version fleshes him out a bit more than the novel does, as if Salles was also instilling some of Neal Cassidy in there as well, which makes sense since he was the inspiration for the character.

I too was impressed by Garrett Hedlund’s performance. I had only really seen him in TRON LEGACY and COUNTRY STRONG, both of which were saddled with weak scripts but he managed to do the best he could with what he was given but with ON THE ROAD he finally had substantial material to work with and from what I’ve read felt very passionately about this project, sticking with it for years, turning down work to keep with it and that kind of passion and commitment translates to his performance on screen. He goes for it all the way and really delivers the goods.

LikeLike

Hi JD. Yes, Hedlund’s very good. What I liked most was how he and the filmmakers resisted making him too much of a Jack Nicholson-esque charming rogue in a movie-star fashion; Salles is more objective. And yet I get the feeling that’s what a lot of critics wanted out of this. You keep seeing the anxiety, the distraction, the mischievous energy, the incapacity to really focus on immediate reality in Hedlund’s eyes, and I felt he revealed a lot about this type of person to me. I hadn’t noticed before researching this that Hedlund played Patroclus in Troy, which was a fairly thankless role but a helluva place to make one’s film debut. Yes, in the book what we see is Kerouac’s idealised avatar for Cassady, whereas here we get more of the real man, with the tension between the character and the vision Kerouac asserts upon him allowed to define the film. As for the film’s strength as a whole, I was reminded often of one of my favourite films, Kaufman’s Henry and June, which similarly digs with a plotless incisiveness into the lives of talented deadbeats.

LikeLike

“But it’s this slightly bitter realism, the acute reflection of the dark and downside of life in bohemia in any era as well as its ephemeral joys, that I liked. And the film is, especially in its concluding passages, true to the Roman candle vividness and floundering yet desirous spirit of Kerouac’s work, a rich and marvel-studded misfire, whilst resisting being another classic illustrated, a demystification that finds raw humanity under the sainted prose.”

Well Rod, I have to this point steered clear of the film due to middling reviews, complaints by a few I know that this isn’t the full version (I don’t know how true this contention is) and my past issues with Sallas, whose THE MOTORCYCLE DIARIES for me was vastly overrated. But my general pattern is to never avoid anything based on heresay, as my avoidance has more to do with scheduling. I will see the film for sure, much as I also took in HOWL, a film i also did not care for at all. Your masterful review, which does well acknowledge some issues is nonetheless a reasonable recommendation, and Garret Hedlund’s performance is winning some attention on the awards’ front. The source material of course is legendary, you have done a meticulous job framing the sociological, political, sexual, cultural and religious elements at play in the original work and this latest film version, embellishing with some persuasive cinematic parallels.

LikeLike

Sam, this film needs a serious and purposeful reboot of the way critics have approached it and I’ve tried to do me bit for that. I loved The Motorcycle Diaries when I first saw it, but I was the right age, and I’ve not yet been visited by any powerful urge to watch it again. This film shares many of its strengths and some of it weaknesses, but strikes deeper into its characters as beings-in-the-world.

LikeLike