.

Director/Coscreenwriter: Alfonso Cuarón

By Roderick Heath

To judge by the early reception of Alfonso Cuarón’s new space adventure movie, it’s the most super-duper, amazing, staggering work of filmic genius of all time, a thrilling successor to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) as evocation of the awe of space, combined with an elementally thrilling, limited-cast survival quest of the likes of, oh, say, The Perfect Storm (1999). With such unceasing and elated praise, a certain level of scepticism going in and disappointment coming out becomes almost inevitable. Cuarón is a talented, observant, technically ingenious filmmaker who can wring a fablelike sense of macrocosmic beauty of some peculiar material, like his 2001 classic Y Tu Mama Tambien, whilst the Harry Potter franchise owed everything to his forcible reinvention of it with 2004’s The Prisoner of Azkaban. He can also be a prissy bore, as his 1998 version of Great Expectations transmuted Dickens’ drama into the worst kind of Miramax mush.

Gravity seems born of the praise for Cuarón’s 2006 scifi dystopian allegory Children of Men, or, more accurately, the praise for the most superficially impressive aspects of it. Cuarón has an interest in and great facility for creating the one technical act by a filmmaker that can still set cinephiles foaming at the mouth in nerdish delight: the epic unbroken shot that seems to defy all inherent limits of perspective and staging. Gravity offers up one at the beginning that takes the form to new heights, seeming to drift as weightlessly as the characters in space whilst recording the action with precision. Indeed, the whole of Gravity is a technical marvel, a sprawling, eye-gorging example of all that contemporary film photography and special-effects units can offer. It’s just that the film is so remarkably banal, even embarrassing, on a dramatic level.

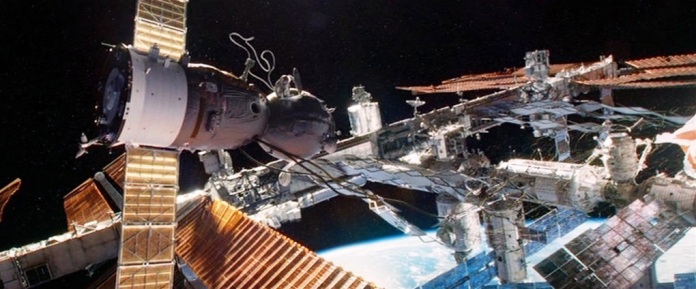

Cuarón’s protagonists are a pair of American astronauts, Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) and Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), introduced nearing the end of a long, exhausting spacewalk from their shuttle, Explorer, to work on upgrades to the Hubble space telescope. Matt is the old hand, on his last mission, garrulously yammering to keep nerves dulled and spirits high, and coaching rookie Stone, a former medico. Fellow astronaut Shariff (Phaldut Sharma) putters idly as word comes through that some sort of missile accident has caused a Russian satellite to disintegrate, and soon, waves of space debris fly toward Explorer. Explorer is smashed, Shariff and the other crew are killed, and Ryan is sent spinning off into the void. Fortunately Matt, who has a thruster pack, also survives the calamity and retrieves her. They make their way back to the ruin of Explorer, and then head on to the International Space Station (ISS), hoping to use the Soyuz modules docked there for an emergency landing. As they near the space station, with Matt’s thruster power running low, they see that the crew has abandoned the damaged station. Can Matt and Ryan make it aboard the ISS and maneuver the damaged craft to Tiangong, a Chinese-manned station?

Standing well apart from the space opera traditions of galactic warships and the like, the more realistic mystique and danger of existence in space has wrung interesting representations from filmmakers for decades now. The James Bond film You Only Live Twice (1967), directed by Lewis Gilbert, commences with a surprisingly, poetically chilling scifi vision of a space capsule being swallowed by another: a spacewalking astronaut’s tether is cut by the closing jaws of the larger craft, leaving him to drift off into eternity. So striking was this moment that Pauline Kael, with a hint of accuracy, said that with 2001, Stanley Kubrick seemed to have fallen in love with it and tried to stretch it out into a feature film. Certainly one of the remarkable aspects of Kubrick’s film is that, whilst sustaining its larger, semi-mystical programme of parable, its fastidious attention to space detail provided a genuinely gruelling sense of life and death in the vacuum in a fashion that felt uniquely authentic, extracting every echoing spacesuit breath and agonising moment of laborious action outside the craft to invoke the dread of the void: many of the film’s most poetic moments are achieved through the conscience avoidance of poetic licence.

Peter Hyams did a good job on a similar level in the belated sequel, 2010, with a memorable sequence depicting a scientist’s (John Lithgow) first spacewalk. Brian De Palma’s severely underrated pop version of 2001, Mission to Mars, sported one amazing sequence of prolonged suspense in which Tim Robbins’ space captain, drifting away from his friends in a spacewalk, finally ends their efforts to save him by removing his own helmet, a climax to one of De Palma’s many scenes of operatic construction and power. By comparison, likening Gravity to 2001 is a bit like comparing Lawrence of Arabia to a Road Runner cartoon because they’re both set in the desert. The exhausting raves for Gravity only seem to prove how deeply the hooks of Hollywood technocrats are now lodged in the general consciousness. I refuse to become used to the repudiation of the need for a first act, where the viewer is introduced properly to characters who are then developed with detail and portrayed with substance, giving the audience time to engage with their individuality and then their plight. The dialogue in the first 10 minutes of Gravity is pitched on the same level of crappy conversational exposition I expect from a ’50s B-movie; only the staging distinguishes it.

Cuarón commences with an immense vista of a gorgeous CGI Earth, slowly allowing Explorer and Hubble and the tiny humans darting around it to drift into view. Cuarón repeatedly returns to similar vistas of the Earth, evidently intending for us to soak in the impersonal grandeur and spiritual significance of the view, but what I got from it was the sense that he’s entered a novel dimension of artistic experience: filming the average college student’s screensaver. But anyway. . . soon disaster erupts, and the serenity of weightless orbit, which Ryan says she could get used to, is abruptly transformed into a churning maelstrom. Apparently the missile accident that starts the havoc was Russian. Ha, those Russians. Wait, what? Are we really blaming the Russians for everything that goes wrong again? Hunks of speeding metal hit Explorer and smash it to pieces, killing Shariff—that’ll teach us to quit doing what Matt describes as a “version of the Macarena” and other goofy acts and behave only in an utterly professional manner. Perhaps he was meant to edge into the role of Doomed Ethnic Guy, except that’s still too substantial. If this film had been made in the ’60s, Shariff would’ve been played by Red Buttons, would have had actual screen time.

After the disaster, Ryan goes spinning off into emptiness unlimited in the film’s most effective shot, directly cribbed from the one in You Only Live Twice. The basic limitations and challenges that Cuarón sets himself are admirable and certainly worthy of a great filmmaker: a tiny cast, little space on either side of the crisis it portrays, no flashbacks or digressions from sustaining a unified authenticity. Except that as Gravity continues, the realism which Cuarón and his production team strive for exactingly and constantly devolves as the pressures of maintaining the sort of breathless thrill ride he’s constructed means piling plot devices, coincidence, and absurdity on top of each other. Spurning the initially cool sense of extraterrestrial physics, the film favours increasingly silly, cartoonish-looking, cliffhanger stunts. When Matt and Ryan make it back to Explorer after the initial disaster, they encounter the drifting, frozen bodies of their shipmates, one of them suddenly looming out of the hull with all the blunt force of a cheap horror movie scare: even the music gives regulation “boo!” underlining.

It’s obvious why Clooney was cast as Matt. He has the kind of stoic, adaptable, good-humoured attitude that only someone who’s starred in a couple of Killer Tomato movies, but whose career survived, can radiate. More importantly, his instincts are strong enough to turn a god-awful line like “You’ve gotta learn to let go” into a professional charmer’s last, weak gag as he gently encourages Ryan to release him to certain death. But Clooney can’t make Matt more than a cliché wrapped in a cliché, a compendium of archetypes. He’s that goofy guy who’s always got a corny story about that time he was in New Orleans to keep things light and earthbound. He’s the veteran superior who’s only a day away from retirement, damn it. He’s the noble, experienced, self-sacrificing captain passing the torch onto his Girl Friday. At no point does he feel like a real person. There’s no fear or pain in him when he tells Ryan to let him go, and Cuarón turns his death into a kind of joke as he goes back to listening to his cowboy music, in a touch that feels like an outtake from Dark Star (1974): now there was a space movie.

And Dr. Ryan Stone, what is she, apart from a woman with an unlikely name? She admits, during a particularly fraught passage through space, that her daughter died in a softball accident, and that ever since she’s been inclined to drive aimlessly, dissociating, until whatever quirk of fate turned her into an astronaut (it seems to be something to do with adapted medical imaging tech she developed). Now, whilst it would’ve violated the conceptual purity of this project (though few things are starting to shit me more than conceptual purity), I found myself wondering what another director might’ve done with this contrast of earthly and celestial wandering, what poetic resonance they might’ve garnered by contrasting the image of a grief-stricken woman driving the lonely Illinois plains and floating high above the Earth. Cuarón can only give me literalism: Matt and Ryan are drifting around to the dark side.

Truth be told, Ryan’s backstory of loss is only brought up to give her the thinnest of emotional identities, and to justify Cuarón’s repeated, deeply corny images of rebirth. Bullock, not generally an actress I like, is restrained and efficient in her role, thankfully. Here, as in many of the film’s numerous, repetitive moments of cliffhanger tension, the visuals and the way the human figures are manipulated within them began to resemble not convincing approximations of space, but rather the sorts of mechanistic inventions found in a lot of completely computer-animated films these days. This feeling gets strongest with a shot Cuarón repeats twice, when Ryan opens an airlock, the interior pressure flipping over and back with cartoonish speed, and her grip suddenly seeming to have become superhuman. Another technically bravura moment depicts the return of the wave of debris, slamming into the ISS and carving it to pieces, with Ryan, who’s been trying to cut away a cable restraining the Soyuz, surrounded by whirling debris and crumbling infrastructure. That Ryan survives such an experience for the second time, this time without even losing her slight grip on her buffeted craft and left completely untouched by a multitude of flying metal shards, seems patently ridiculous.

The sensation that Gravity represents the Pixar-fication of “live-action” cinema increased with every passing minute. It reflects the same delight in turning a ruthless movie scenario into a mechanistic, Rube Goldberg construction. Logic and likelihood seem aspects Cuarón and his coscreenwriter, his son Jonás, decided to avoid early on to concentrate on sheer rollercoaster thrills, plus Cuarón’s getting at something the crystallises in the film’s most amazingly bad sequence. Ryan makes it aboard the ISS after being forced to abandon Matt, a moment that’s curiously unaffecting, partly because Matt’s demeanour of professional acceptance and humour doesn’t waver. Matt has alerted Ryan that the debris field will be returning about 90 minutes after the first strike judging by the speed it’s moving in orbit, and when it comes back it destroys the ISS and almost takes out Ryan’s Soyuz. The 90-minute interval seems set up to accord closely with the film’s initial real-time mission brief, for Gravity runs just over an a hour and a half, but Cuarón throws that felicity away as he plays games with story progression in the last third. Ryan’s first entrance to the ISS sees the wryest of Cuarón’s several nods to earlier scifi films, as Ryan strips off her spacesuit to reveal her lithe female form beneath, evoking the famous opening zero-g striptease of Barbarella (1967), but with sniggering sexuality replaced with the grace of mere biology. Except that Cuarón instantly gets too cute by having Ryan curl up in a foetal ball, to underline her own renaissance, and possibly invoke the star child of 2001, but only achieving the status of laboured symbolism. This isn’t the only moment in the film where one of Cuarón’s better touches segues instantly into one of his worst.

The cinematography of Emmanuel Lubezki is, as expected, superlative throughout, though as Christopher Doyle complained about last year’s Oscar-winning Life of Pi, to what extent a film as relentlessly post-produced as this can be said to be have photographed is increasingly dubious. Lubezki shot the last film to earn a lot of 2001 comparisons, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011), and he has a gift for making even mundane objects seem blessed to exist and bathed in holy luminescence. But whereas Malick’s loopy epic shared a vital trait of thematic adventure and aesthetic risk with Kubrick’s work, Cuarón’s film is infinitely more conventional on all levels but the technical. Kubrick took risks to offer up his space-age tale as a metaphor for the search for divine transcendence one can’t imagine a contemporary big-budget filmmaker being allowed to take, and indeed now, his work was largely greeted with querulous confusion. By comparison, Cuarón’s attempts to invoke religious, spiritual, and philosophical dimensions to his tale range from the cringe-worthy to insulting. After the ISS’s destruction, Ryan is left alone in a seemingly broken-down craft contemplating a solitary death. Again Cuarón offers up one of his best moments here, as Ryan contacts a Japanese ham radio operator and begs him to listen to the barking dogs and crying babies she hears in the background, and begins forlornly howling along with the dogs herself.

There’s riskiness here, an embrace of a note of black comedy as well as a threat of existential absurdity that does achieve something like what Cuarón’s aiming for. But he immediately destroys the effect as Ryan moans, “Nobody ever taught me how to pray!” Give me a fucking break! The film’s dramatic credibility slides precipitously towards the level of a bad soap on a Christian TV channel. Ryan decides to die by turning off the air supply, but Matt, either his shade or Ryan’s feverish, oxygen starved imagining of him, returns and lets himself into the Soyuz to give her pep talk and tell her how to get out of her fix. I will admit as this crap piled up, I very nearly left the movie theatre. A good genre smith would’ve let the angst, the fear, and the desolation in the story all speak for themselves, but Cuarón pretentiously underlines his points in such a way to only highlight how obvious, slick, packaged, and greeting-card-worthy the sentiments here are. We couldn’t just take it for granted that the woman doesn’t want to die and would like to get back to Earth. Cuarón’s presumption to evoking cosmic awe and human frailty in the face of infinite has, lurking behind it, a religious presumption that’s as tinny as a late-night preacher’s homily. One has been warned of Cuarón’s fondness for cheesy symbolism before: to wit, the ship called “Tomorrow” that picks up the heroes at the end of Children of Men, but that was more forgivable as it was akin to a sort of sign-off admission of the story’s fable qualities after constructing his world with some rigour. Here the lurking stickiness of vague New Age spirituality is recalled right at the end as Ryan breathes a grateful thank you, perhaps to God, perhaps to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Or are they the same thing? Of course they are.

There’s no real curiosity about the universe, about the nature of humanity, the contrast between the scale of space and the finite nature of human endurance, to be found here. This is a popcorn-selling, fantasy-action film, no mistake. Some are celebrating it as a riposte to the emptiness of many special-effects blockbusters, and yet it’s no smarter than many of those; in fact, in some ways it’s interchangeable with them, and in other ways worse. At least Avatar (2009) had some actual ideas. Gravity has lots and lots of scenes of Sandra Bullock trying to hold onto metal bars in repetitive cliffhangers. Indeed, consider the title’s similarity to Bullock’s star-making vehicle, Speed (1994), and the close relationship of the two works emerges. Perhaps the greatest lack here is any kind of story complication that might have offered some moral or actual psychological depth, a la Tom Godwin’s famous scifi short story “The Cold Equations,” or various cinematic permutations on it (like precursor realist space movies Destination Moon [1951] and Marooned [1969]). Structurally, Gravity is another recent movie that owes quite a bit to video games as well as Pixar, with its first-person shots and the series of rolling crises that defines the story to quite ridiculous lengths. Really, the tidal wave of technical carnage takes out every satellite, which are all on exactly the same orbital level? Can your average spacesuit really take that much punishment? Are we really supposed to swallow Ryan being saved by the ghost of Matt? Because make no mistake, Matt’s reappearance does have a functional effect on the story: he tells Ryan how to get the Soyuz going and get to the Chinese station. Can we buy this as Ryan’s subconscious telling her how to do it? Either way, it’s really stupid.

Some proponents of the film have dismissed the validity of remarks on its science and implausibilities, as if this was somehow incidental in a film that’s being sold around its realism. I’d like to say that at least on the level of a thrill ride, I enjoyed Gravity, but even there I’d be stretching it somewhat. I often found the film’s technical cleverness to work against the nominal effects it was trying to achieve—the sense of claustrophobic vulnerability violated by the camerawork, the keynote of physical danger degraded by the precision control of the special effects, which, in spite of their grandeur, still rarely looked like actual objects that pose immediate tactile danger to the actors. The opening single shot is deeply admirable as spectacle, and yet I felt irritated by it on a fundamental level: it’s nothing, really, that the many recent fake-found-footage filmmakers haven’t already done. Certainly, this manner of filming has come on in leaps and bounds since Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) had to awkwardly hide cuts in close-ups. Now all sorts of astonishing, reality-jamming things can be accomplished. But the reason why so many filmmakers, critics, and theorists cream their jeans about unbroken tracking shots it’s because they’re supposedly more realistic and offer a more open sense of detail, a challenge to the usual precepts of movie construction, direction of attention, and coherence of space and time.

Such shots in a film like Gravity are more like an extended stunt, not provided to give detail but to wow with how good the staging and effects are. Instead of the potential to awaken the viewer’s receptivity, here it helps to narcotise it, to make us stop paying attention to details and give ourselves up to the experiential haymaker. I will admit to betrayed expectations. This sort of story seems to me more fit for a dark, meditative, mostly psychological thriller, rather than a pompous arcade attraction. Steven Price’s clod-witted scoring has all the subtlety of a day-glo thong. Cuarón has only done one major work not based on strong preexisting material, and that was Y Tu Mama Tambien: if not for that film’s quality, I’d readily put the weakness of this one down to the lack of such a basis. As for the finale, well, remember how Apollo 13 (1995) went into all that detail about descent trajectories and how if they’re not met correctly, you burn up? Yeah, well apparently that doesn’t matter in a Chinese space capsule. Yeah, that was another good space movie. Finally Ryan crawls out of a lake that somehow looks faker, more generic and art-directed, than the space she’s just been in: the real world has become phony.

Rod you’ve hit so much on the head here. Not having seen this particular film I can’t agree except by what you’ve pointed out, but boy what you’ve pointed out is how I see so much of film and television going for that matter. Big Bang with no fallout, no substance at all. Thanks for this I had thought about it but was waiting for someone whose opins were trustworthy and was expressed so that even I, a long haired leaping gnome would make heads and tails of it. You did and I don’t….want to waste my time on bad films.

LikeLike

Well, I kinda wish you had watched the film so you’d really know if I’m right or not. Isn’t that just the big Catch-22 of film commentary?

LikeLike

Plenty of substance, could not possibly disagree more. The deserved tremendous reviews (I bring this up only because you broached in your opening paragraphs) are NOT just in the Hollywood fraternity, but in the U.K. and worldwide. It’s not my absolute No. 1 film of the year to this point (that would be 12 YEAR A SLAVE or SHORT TERM 12) but it’s top drawer. Your review hence is most unique, though as always I applaud your impassioned writing and epic treatment, and just acknowledgement of Lubezki’s work. No CHILDREN OF MEN was NOT superficial at all–it was one of the very best films of its year , and no I do not think or believe there has been any serious attempt to make claim that GRAVITY is on par with 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY aside from the obvious parallels. They are two completely different animals. GRAVITY is hardly banal by any barometer of measurement,

But fair enough. Our tastes remain far apart nearly all the time. But heck, that’s what makes the world go around. The point is that you defended your position quite admirably.

LikeLike

Hi Sam. Would that we were reconnecting after a long time under most felicitous circumstances. I hope you’re feeling better — tales of your and family’s recent travails distressed me. Ah, I admire your capacity to deliver praise to criticism you wholeheartedly disagree with. I wish I had that tolerance.

But I did not call Children of Men superficial, Sam. I said the praise it received was largely for its most superficial aspect.

“…no I do not think or believe there has been any serious attempt to make claim that GRAVITY is on par with 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.”

You’ve obviously read very different commentary to what I’ve read.

LikeLike

Rod, I must appreciate those very kind words. I have been feeling much better after some recurring kidney stones and the procedure that followed. Lucille is now taking the prescribed medicine, and I am confident all will be well for a very long time to come as is usually the case with that condition. Your concern is deeply appreciated.

Well, I had no hard feelings for a number of months as it is. The original WitD site divergence occurred on Monday, March 25th. I did place glowing comments under your spectacular tribute to Ray Harryhausen on July 4, and a few weeks earlier (on June 15) for your excellent essay on STAR TREK: INTO DARKNESS. I hope to be more active in the coming months as the movie season hits its stride.

I understand what you are saying about CHILDREN OF MEN. I worded it incorrectly for sure. But my point remains that the superficial aspects for which you decry the praise are not superficial for me.

I have read plenty of GRAVITY vs. 2001 comparisons, but I didn’t quite see an effort to make claim that Cuaron’s film was as great a work of artistic genius as Kubrick’s. To be honest, as much as I do like GRAVITY quite a bit, it does NOT approach 2001. I will draw the line there. Ha!

Thanks again for the moving words.

LikeLike

Good to hear everything’s okay, Sam.

LikeLike

Oh, how you nail it, esp. when you say “The dialogue in the first 10 minutes of Gravity is pitched on the same level of crappy conversational exposition I expect from a ’50s B-movie; only the staging distinguishes it” and “But whereas Malick’s loopy epic shared a vital trait of thematic adventure and aesthetic risk with Kubrick’s work, Cuarón’s film is infinitely more conventional on all levels but the technical” and “Some are celebrating it as a riposte to the emptiness of many special-effects blockbusters, and yet it’s no smarter than many of those; in fact, in some ways it’s interchangeable with them, and in other ways worse.”

I remember as my wife and I were walking home from the theater, we got all the nitpicking out of the way, all the kinda dumb moments (king for me was the subtly chauvinist “ghost rescues girl” moment), all the stretches of believability, the slow and steady escalation of UNbelievability… and settled into the more forgiving “but, man, what a great thing to look at – you really felt like you were there” acceptance. Then, as the days went by, and more and more praises were heaped upon it by friends and reviews, the less that “great thing to look at” approach seemed to support it. That’s when I turned into a curmudgeon about it – as it slowly morphed into the Argo of this year – the one that everybody loves but I end up hating the more I think about it. Your review heals me in its own way, as it gives (yes) gravitas to what I’ve felt for weeks now. It’s not that it’s a bad movie, it’s that it’s an okay, fun experience being elevated before my eyes into something of un-sullyable cultural import. It’s as if the 3D glasses we all wore were achieving the reverse They Live function – making everyone see what’s NOT really there. Or something like that – you get my point. It simply ain’t what they’re all making it out to be. It’s sad when the only fully saving grace of a movie for me is that (as I found out later) the end-of-movie lake is the same one where they shot the beginning of Planet of the Apes. I hope that’s true, or this movie completely falls off my radar very very soon.

LikeLike

Hi Rob. Seems we’re often as simpatico as Sam and I are at odds about new movies.

The contemporary obsession with immersive, you-are-there impressions in film-making, which is a thing in both mainstream and arthouse cinema today if accomplished in different ways, is deeply boring to me, even as it is, obviously predicated around sensually overwhelming effects that should be the opposite of boring. Whilst the “this year’s Argo” is a fair and obvious comparison, I found it more like this year’s Life of Pi, a technically marvellous work built around a story and set of basic ideas that strike me as corny and juvenile. We are expected to be obeisant to these acts of “great artistic vision”, but the vision we get from these major filmmakers with special effects units at their backs isn’t the kind of vision that gave us Apocalypse Now or Heaven’s Gate, based in a desire to expand the palate of mainstream film on several levels: these rather reduce the palate of film on all levels except the production. No, this isn’t a terrible film, nor even a bad one, but it is a quietly egregious work. For one thing, Cuaron’s technique and conception, and all his choices stemming from these, though impressive, for me retarded the impact of the story he tried to tell.

“It’s as if the 3D glasses we all wore were achieving the reverse They Live function – making everyone see what’s NOT really there.”

Don’t you just get that feeling a lot?

“…the subtly chauvinist “ghost rescues girl” moment…”

That whole scene encapsulated everything both good and bad about the movie, first the good and then the bad. Interestingly, the Wikipedia synopsis amongst others assume that Ryan was just hallucinating with too little oxygen, and that the hallucination of Matt’s return just jogs loose something in her mind. Now, whilst this is more probable, it still begs a lot of questions, considering that Ryan’s a neophyte technician with little knowledge of the systems of the crafts she’s commandeering. It only makes sense, really, if it is Matt’s ghost, in other words, and that’s just stupid, so we’re locked in a paradox. Either it’s an absurd point of inspiration for someone who doesn’t know much about what she’s doing, or an excruciating deus ex machina. It’s like the film’s religious elements, which a major proponent of the film said to me online the other day he can’t understand why people like me take it at face value; if Cuaron doesn’t want it taken as is, on the evidence presented to us on screen, then he should have found others ways to handle it. Because I’m only responding to the cues I’m being given.

“…the end-of-movie lake is the same one where they shot the beginning of Planet of the Apes.”

Wow, really? Maybe during the credits Ryan gets dragged off in a net and renamed Bright Eyes.

LikeLike

“Steven Price’s clod-witted scoring has all the subtlety of a day-glo thong.”

Now that’s a truly priceless sentence.

LikeLike

Although it does perhaps scarily reveal how much day-glo thongs weigh on my mind.

LikeLike

Speaking of the score, my other favorite dumb moment is when Matt says something poetic about the silence of space, and the camera floats over to the earth, supposedly to offer us a moment of sublime quiet – but the score continues over the shot! Music to cue us to fall under the spell of silence – that’s a new one.

“…predicated around sensually overwhelming effects that should be the opposite of boring” – like a hard rock song with a relentless, pounding rhythm that can actually put you to sleep. It reminds me of my trip to Ireland in 2012, driving the most-of-the-day coastal loop around the Ring of Kerry – by hour four or five, I was shocked to realize I was actually USED TO the most gorgeously green and blue scenery I’d ever laid eyes on. The adage “too much of a good thing” is sadly apt, especially now that I am/society is nurtured on the idea of yeah, what’s next? But it partially explains why, by hour two of Gravity, I needed more than just more incredible scenery, more than just more super intense obstacles and, especially, more than just someone to merely like (they were likable but shallow), I needed someone to care about.

As for the “hallucination vs spectral deus ex machina” debate, I’m gonna have to go with the former – if it was a ghost (I realize I called it a ghost earlier), then she wasn’t dreaming, and the ghost’s opening of the hatch would have introduced her to the harsh realities of wearing only underwear in space (day-glo or otherwise). As it plays in the film, her utter lack of reaction most surely means she was hallucinating the entire event. But the fact that this is all we’re open to debate on anything approaching a psychological angle in this film is more than enough to disqualify it from anything major, award wise (outside of special effects) – but I’m afraid we’re in for a frustrating awards season, so long as this one has such stellar reviews, if you will.

LikeLike

Rob, that is indeed the best argument for the hallucination interpretation, although I don’t suppose it’s impossible with ghost logic that he could seem to enter the ship in a similar fashion. Ryan doesn’t not react; remember she curls up afraid of the zero-Gs and then finds nothing happened. Oy, this argument got silly real fast. Of course it’s not a ghost; but the other explanation just reveals the dippiness of the moment, the fact that Cuaron wants to con us, just even for a moment, into thinking Matt’s alive and has made it back, is just wretched. Your “too much of a good thing” is of course apt. I’ve seen many filmmakers who can sensitise me to unusual spectacles and textures of time and experience. Stalker is a film about attunement to an environment on a genuinely communicative level. Okay, extreme arty egghead example, but still. This, to me, did anything but, except on that raw level of, “Ooh, pretty.” Think about the opening vistas of Blade Runner. Spectacular. Immersive. World-creating. And then there’s a fucking story. I think our basic point in common is that once the wow factor of the visuals is factored out, this falls apart and reveals lack of substance on just about every level. Of course, lots of folks seem to believe the wow factor is important unto itself; moreover, that it creates its own context and justifies its own existence, but I don’t buy that. I don’t see why the film had to be shaped this way; this is a stunt. Can you imagine a film like Aliens, where it takes upwards of an hour before absolutely anything resembling action kicks off, being made in such a fashion today? Now once the action in that film starts, you damn well know it, and you know the people it’s happening to. Here I have a fact sheet in place of people.

LikeLike

Stalker! The closest Tarkovsky ever came to telling a “three guys walk into a bar” joke. That movie! For a film as slow and quiet and long as it is, I was riveted the entire way. Just saw it about three or four months ago, and – per your environment comment above – I can still recall how it made me feel like I’d just rolled around in wet, sloshy marsh. That doesn’t sound like a ringing endorsement, and indeed it’s not going to be, for anyone who’s not inclined toward his cinema to begin with . Definitely a “deep cut” in his canon. But yes, all that work he did to create that murky, cold environment, it’s all toward a meaning or message or, at the most fundamental, throwaway level, a TONE. Gravity (which is such a whiplash to consider in the context of Tarkovsky or Kubrick or even Cameron) has no discernible tone, outside of “manufactured” and no discernible message, outside of eat more popcorn. (Don’t feel obligated to respond yet again to me – I could go back and forth on things I don’t like all day – or night, depending on your hemisphere.)

LikeLike

“Don’t feel obligated to respond yet again to me.”

Ha, well, still, I don’t like to leave a person hanging. Your comments on Stalker and its characteristics are of course right on the money (and of course I’ve commented on it at length some time ago) and do elucidate what we’re getting at in the failures of Gravity. I was contemplating it further last night and my feeling that the film’s showy technique dampens what it’s supposed to amplify has become even stronger. A person in Ryan’s situation ought to be conscious of how their universe, far from being expanded by such a position, must actually, necessarily be reduced to almost literally the two inches in front of them; that’s all the connection they have to life. Leaving aside other aspects, Kubrick managed that brilliantly in the way he stripped down the sound in 2001; the echoing, unnerving breathing and lack of dialogue in most of the exterior scenes when Frank and Dave go spacewalking emphasises this weird mix of vastness and utter claustrophobia. Gravity despoils the effect by making everything so damn chatty and pretty, and by using camera motion and edits to speed the action up to a reasonable blockbuster pace, rather than the laboriousness Kubrick emphasised. I would however say that if Cuaron’s efforts do have a knock-on effect and inspire more of what I suppose could be called “realist blockbusters” then I’d consider it a worthwhile exercise.

LikeLike

If you’ve just coined a phrase, I’ll do what I can on this end to spread it around – “realist blockbusters”… It’s almost oxymoronic.

Just clicked over and read your Stalker piece – beautifully written. And I like what your reader, Boris, had to say there at the far bottom of the comments, about it being so close in spirit to a horror movie without ever becoming one. I’ve just recently rewatched Ivan’s Childhood, Rublev, and Solaris, and added Stalker to the SEEN column – have yet to tackle Nostalghia and The Sacrifice, and can’t for the life of me remember if I gave The Mirror a whirl back in college or not…

If you haven’t noticed, I’m trying desperately here to run the opposite direction from Gravity. Perhaps I’ll try to forget it exists and fire up a Tarkovsky…

LikeLike

Here’s my favorite line: “By comparison, likening Gravity to 2001 is a bit like comparing Lawrence of Arabia to a Road Runner cartoon because they’re both set in the desert.”

I enjoyed it as a fantasy-thriller and for the cool, super-special 3-D effect, but there’s no depth to this at all. The evocations of God and religion are thin and predictable (those closeups of icons or Buddhas on the space station control panels – gaah!) Clooney’s smooth wisecracking annoyed me, but Bullock was fine. And that’s about it. I think EUROPA REPORT, a found-footage space thriller on which NASA was an active collaborator, was a better film on nearly every count.

LikeLike

Hi Pat. I gotta see Europa Report, as it seems to be one of those movies about ten people saw, but I know them all on Facebook and they liked it. Yes, I was surprised how much Bullock holds up her end in the film. As I said in the review, she’s not my favourite actress, but she’s restrained and unmannered in this. A lot of other actors would’ve gone for histrionics. As for the film’s engagement, or lack thereof, with larger themes, well, it feels to me now like this is very close to being a Rorschach test for the individual viewer’s sensibility in that regard, with Cuaron’s employment of touches as you mention reminding me of a sort of crypto-spiritual product placement, hoping you’ll buy this as serious.

LikeLike