.

Director: Ivan Reitman

By Roderick Heath

Ghostbusters is one of those quintessential films beloved by anyone who grew up in the ’80s. It’s also one of those films whose cultural familiarity partly masks what a peculiar beast it is. Dozens of films since its release have mimicked and taken cues from its atypical mix of apparently disparate genres and impulses, as it practically gave birth to the “high concept,” self-aware blockbuster. What is Ghostbusters? A horror film? A screwball farce? A send-up? A blockbuster action flick? A self-reflexive, postmodern disassembly of popular moviemaking? A wild and self-mocking jaunt from a team of semi-outsider comics who found themselves armed with all the resources of powerful insiders? All of the above?

Just whose success it is likewise remains confusing. Director Ivan Reitman handled the film well, easily standing as his best work, and the screenplay concocted by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis is smart and original. But the film is more distinguished by the rare and elusive chemistry of its many constituents. Perhaps the most notable follow-up success by its participants is the Ramis-directed Groundhog Day (1992), which starred fellow Ghostbusters alumnus Bill Murray and represented a clear development on Ghostbusters’ heady side. Aykroyd’s efforts to delve into the same zone of satirical black comedy with his own debut directing effort, Nothing but Trouble (1990), is a delirious mess, whilst Reitman’s follow-ups were generally so commercially crass as to beggar belief.

Ghostbusters is also its own success story, and in that regard, it’s still an eccentric, subversive experience, encouraging the audience to cheer the heroes whilst also mocking Ghostbusters‘ own marketing iconography, incorporated within a hall of mirrors in which art reflects life and commerce. The basic theme, a ragtag pack of shonky savants eagerly practising alternative capitalism surprise everyone not only by becoming successes but also by saving the world, is inseparable from the film’s background. It was made by veterans from corners of show business leagues removed from the halls of Hollywood power who nonetheless gave popular cinema an urgently needed shot in the arm. Reitman had started as a no-budget filmmaker in Canada making the comedy horror film Cannibal Girls in 1972 with Eugene Levy, an alumnus of the Toronto branch of Second City, now an improv dynasty that was born in Chicago. Murray, Akyroyd, and Ramis were likewise Second City veterans, with Murray and Aykroyd initially finding bigger fame on NBC’s Saturday Night Live. Murray was vaulted to minor movie stardom when he ventured north of the border to work with Reitman on the raunchy farce Meatballs (1979), one of those cheap, inglorious little movies that sometimes make the people who make them very rich. Ramis joined Reitman and Murray for the hugely successful Stripes (1981). Meanwhile, many of the artists from Saturday Night Live and SCTV, a television spinoff of Second City Toronto, gained cinematic attention in movies like Steven Spielberg’s 1941 (1979), and John Landis’ The Blues Brothers (1980) made Aykroyd and costar John Belushi major comedy stars. The joining of these two streams was perhaps inevitable, but it happened only after Belushi’s tragic death forced Aykroyd and Ramis to retool the script they had written for Murray to star.

Ghostbusters harked back to traditions older than the fringe comedy scene its creators came from, however. Comedy-horror had been a hugely popular genre in the 1920s and ’30s on Broadway and in the movies, as American entertainers made light of darker European-derived fantasies. Examples include the much-filmed play The Cat and the Canary, the 1939 version of which starred comedy titan Bob Hope, who followed it up with The Ghost Breakers (1940). The suggestive similarity of that title and Ghostbusters accords with their approach to the material: taking a genre gothic chiller that unfolds in a straightforward manner with all the usual paraphernalia, but sticking a comic bumbler in the foreground to strike sparks against the material. Likewise, Akyroyd and Ramis were witty enough to take a surprisingly rich and dramatic, H.P. Lovecraftish tale and populate it with characters who are barely functional in the real world. Murray’s character, Peter Venkman, has elements of Hope and Groucho Marx to him, whilst also belonging to a comedy type just starting to wane, but had been the backbone of American film comedy since Robert Altman’s MASH (1970): the slightly boorish, horny, bratty goofball whose only, vague claim to heroic status is that he hates authority and pretension, a figuration that reached its reductio ad absurdum in Belushi’s Bluto in National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978). The Ghostbusters are, indeed, very much like the Animal House or Meatballs characters a few years older and scarcely wiser, now growing off the body of academic culture like warts, but faced finally with sink-or-swim survival in the world of ’80s yuppiedom.

Venkman is introduced engaging in an experiment that spoofs the fuzzier end of ’60s and ’70s research, including the infamous Milgram experiment, as he nominally tests two volunteers for ESP abilities, delivering electric shocks when they get an answer wrong, except, natch, that he’s only shocking the nebbish guy (Steven Tash) and pretending that all of the gorgeous blonde’s (Jennifer Runyon, who is married to Roger Corman’s nephew Todd Corman) answers are right. Venkman works in the Dept. of Paranormal Research at Columbia University, along with the more efficacious lab rats Ray Stantz (Aykroyd) and Egon Spengler (Ramis). They interrupt his flirtation to drag him to the New York Public Library, where, as the pretitle sequence has shown, a mysterious entity has terrified a librarian (Alice Drummond). The trio encounter the entity, seemingly the shade of a dead librarian, but when they decide to tackle it, it morphs into a demonic grotesque that sends them running for their lives. The unexpected quality of this scene infuses the film as a whole although it never tries to top it. Venkman quips his way past supernatural manifestations (“No human being would stack books like this,” he mutters after Ray points out a pile of volumes that resemble an historically documented poltergeist incident) before they run into, and then away from, the spectre which proves genuinely fierce and frightening. The comedy disarms before the ploy of scaring the audience as well as the heroes, only for the fright to revert to joke once more.

Although it quickly nullifies the power of the uncanny as a source of dread, Ghostbusters never entirely quells it as a source of lawless power, and this sequence illustrates how, stepping nimbly between tones. Tim Burton may well have felt encouraged to make his even odder mixture, Beetlejuice (1988), during the brief window when real weirdness was welcome in the realms of high box-office cinema. Although met back at the university by a snotty dean (Jordan Charney) who terminates their grant and evicts them from campus, the boys find their true path, as Peter encourages Ray and Egon, who have learnt from their encounter how to trap and contain a ghost, to start a ghost-catching business. By the end of the second reel, thanks to a crushing mortgage on Ray’s ancestral home, the trio have set themselves up in an old fire station in lower Manhattan (outfitted to tackle “all your paranormal investigation and elimination needs,” as their tacky TV ad puts it) and hired a wiseacre secretary, Janine (Annie Potts). The business of commercialism as the new inescapable paradigm in the go-go ’80s is a key conceit in Ghostbusters, echoing outwards into life, as the boys’ company logo is also the film’s advertising image and the idea of paranormal battle as just another home service industry gave the film’s inimitably bouncy theme tune, by Ray Parker Jr, its refrain. It feels like Aykroyd and Ramis’ cheeky way of admitting they’ve sold out the modest, DIY spirit that fuelled the old comedy scene, but doing so in the most cunning manner possible—getting busy with the ’80s special-effects blockbuster.

Murray’s act was tweaked to best effect in Ghostbusters as the closest of the trio to a romantic lead. Peter starts off as a cynical prick—the dean is right when he remarks that Peter regards science as “some sort of dodge or hustle”—but he grows up in the course of Ghostbusters without letting himself admit it nor disappointing the audience with corny reversals. Rather, he contends with actual adult emotion and potential heartbreak with the same humour he offers to ghostly slobs and incidental aggravations. Venkman’s smart-ass smirk communicates his inability to care about the things everyone else cares about, and where Bob Hope’s heroes were hilariously craven, Venkman alternates between egocentric, on-the-make douchebaggery and an underlying attitude of careless disdain for reality, which makes him the ideal man to wade into battles with otherworldly entities, extradimensional deities, and possessed girlfriends, because they strike him as scarcely more weird or unsettling as the petty authoritarians and “normal” people strewn in his path.

Ray and Egon, by contrast, are more traditionally nerdy, Ray rather boyishly earnest whilst Egon, with a jutting crown of Eraserhead hair, brings a quality of haughty, Euro-tinted cyberpunk cool to the team, seemingly the most serious of the trio, but also, as Peter’s anecdote about him trying to drill a hole in his head indicates, the most bizarre. Ramis is the film’s richest alternative to Murray for throwaway humour, given to grimly hilarious exhortations (“I think that could be unbelievably dangerous.”) to too-late warnings (“Don’t cross the streams.”) to esoteric interests (“I collect spores, moulds, and fungus.”). One reason, I think, why kids liked the characters so much, even as a lot of the humour and the concepts of the film went over our heads, lay in the essential boyishness of the Ghostbusters, especially their disdain for both “parent” figures like priggish EPA snoop Walter Peck (William Atherton) and for property. Their efforts to extricate a poltergeist from a ritzy hotel causes more damage than the spirit ever could, evoking the Marx Brothers destroying a place to save it; Venkman takes his chance on the old whip-the-tablecloth-off-the-set-table stunt just for the hell of it. There’s a flavour of Aykroyd’s writing on The Blues Brothers, as he sent his asocial heroes crashing through shopping malls and annihilating great swathes of consumerist folderol.

The hotel manager sniffs at paying the ridiculous bill Venkman hands him for their services, but, of course, the threat of releasing the monster again is all it takes to gain submission. The boys’ victory here is their first, though the hotel only represents their second client, after concert cellist Dana Barrett (Sigourney Weaver), who reports the startling appearance of demons uttering the name of an ancient Sumerian god in her refrigerator. Dana’s intrusion into the lives of the Ghostbusters prods Venkman to mature, albeit it unwillingly and with customary insouciance, as he tries to impress a woman not at all impressed by his smug shtick (“You seem more like a game show host,” she says in comparing him to other scientists) but who enjoys his energy and ironic charm. Unbeknownst to all, Dana and her neighbour in the building, accountant Louis Tully (Rick Moranis), have, because of their addresses, been chosen by mysterious forces to become the “Gatekeeper” and “Keymaster.” The sexual innuendo isn’t subtle and yet the layering of the humour is, as the film signals understanding of the erotic underpinnings of much symbolism in the horror genre, but doesn’t overplay this epiphany. Instead, it’s married to a style of comedy practiced by most of the cast in other venues, one based on well-observed social types. The garrulous, dorky, socially malformed Louis, who is Dana’s excessively attentive neighbour (and also constantly locks himself out of his own apartment) finds his ticket to getting it on with Dana as the Keymaster, albeit after being possessed by a dog-monster.

Louis’ party, to which he invites Dana, is one of the film’s quieter comic coups, as he raves to the gathered about throwing the bash “for clients instead of friends” so he can claim it as a business expense, shouts out the details of his guest’s financial problems, hurls coats carelessly out onto the balcony, and dances to disco (in that grey zone between when it was cool and when it became retro hip) with a buxom blonde, before the demon sent to claim him crashes in through the window. The film’s half-cynical, half-affectionate feel for New York emerges properly in the following scenes, as Louis flees the monster, only to be caught by it before a restaurant full of snooty diners, who momentarily pay attention to his desperate cries for help before turning back to their meals. Then the now-possessed Louis screams incoherently about obscure apocalypses before being picked up by the cops and taken to be interviewed by a cautiously fascinated Egon, where he unleashes an enthusiastic monologue about the grim fates that befell previous worlds that became victims of his overlord Gozer. Whereas Louis’ possession is played for comedy, Dana’s returns to a note of genuine weirdness, as, preparing for a date with Peter, she sees something terrible straining at the door to her kitchen. Monstrous arms sprout out of her chair to grip her and drag her to the beast.

One aspect of Ghostbusters I particularly admire today is the way it creates its own detailed, enriching, peculiarly straight-faced mythology and tropes (e.g., the eternally intriguing “Tobin’s Spirit Guide”), and plays the character-based comedy out against that background, only combining the two occasionally for judicious effect, particularly in the finale in the eventual form Gozer takes. There’s youthful indulgence and cleverness to the details of their Ghostbusting business, from the fire pole they slide down to leap into action, to their jazzed-up station wagon dubbed Ecto 1, like a down-market, second-hand Batmobile. The script profitably avoids mere supernaturalism as it takes the boys’ pseudo-science interests literally, presenting the ghostly outbreak as the result of an “interdimensional cross-rip.” The fantastic dimensions then erupt into the “real” world via a portal created for it by the mythical, insane architect and surgeon Ivor Sandor, a wonderfully Lovecraftian detail. It also reconfigures the basic plot of the stultifyingly bad The Sentinel (1976) and capitalises much more successfully than that film did on the notion of uptown glamour colliding with infernal underworlds; as with Cristina Raines’ heroine there, Dana is the quintessential classy lady confronted with eruptions of the uncontrollable and terrifying. The possessed Dana is transformed into a randy minx swathed in gossamer red, like the girl in a dance club you most regret going home with, levitating and finally driving Venkman to the most unusually disturbed and unguarded request to “please come down.” Weaver, hitherto best known for Alien (1979), got to revise her image and her career here.

Reitman’s sense of style is also unusually textured, especially during the superbly composed sequence in which the Ghostbusters’ ghostly horde, released by Peck in his determination to establish the pecking order, floods out of their building in a thunderous light show and terrorises the city. The streams of ectoplasmic energy all converge on Dana’s building to the strains of Mick Smiley’s marvellously odd synth-pop epic “Magic,” as if the whole affair is some extraordinary new-wave art installation gone horribly right. Similarly good is an earlier montage sequence that portrays the Ghostbusters riding to fame and success whilst plying their trade, extending the film’s jokey, but incisive incorporation of modern celebrity as a reality unto itself. The boys’ adventures are reported by Larry King and Casey Kasem, and their images are plastered all over magazines, Egon’s ingenious, but dangerous proton-accelerating, ghost-busting packs shown off in the same fashion as the latest model iPhone.

Much of the film’s visual strength might be laid at the door of the high-class contributions of cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs and special-effects maestro Richard Edlund. Kovacs’ look for the film, sleek yet richly grained and filled with earthy hues, manages to combine a sense of urban grit with groves of romance and bizarreness, seeking out signs of an antique, even fantastic world coexisting with the decay and bustle. Emblematic of this approach are the stone lions outside the public library that prefigure the gargoyles in which Gozer’s demons slumber and the atmosphere of an older New York, represented by old quipsters lurking in hotel lobbies, encoded in the old panelling of the hotel and the art deco interior of Dana’s building.

The grounded feel in a time and place, as well as humour and characterisation, holds the movie together as it charges into zones of special-effects spectacle and informs its final, celebratory air as a hymn to rowdy all-American energy. The Ghostbusters have since gained an extra recruit, Winston Zeddemore (Ernie Hudson), a blue-collar black dude who is no PhD, but gives the team their link to the ordinary world around them with his adaptable good-humour (in response to a series of woolly-minded questions on the application questionnaire, like “Do you believe in the Loch Ness Monster?”, he replies, “As long as there’s a steady pay cheque in it, I believe anything you say.”) and workaday attitude to utter insanity. Winston’s addition exacerbates the Ghostbusters as a gallery of types and increases their Dumas-esque cache as the three musketeers become four. He also provides the film with one of its most textured moments, the kind of moment that lifts the film to a much higher level than it might have, as he prods Ray about religious beliefs; he is the first to make the link between the exploding demand for their services with an oncoming event of “biblical proportions.”

Although Atherton’s performance is effective (to an extent that made him a go-to guy for playing smarmy creeps), the conflict with Peck is easily the film’s most canned element. It bespeaks an irritatingly regulation ’80s contempt for bureaucrats in general and the EPA in specific, and exists chiefly to justify a plot point—the release of the captive ghosts, and a little pay-off for the guys when the Mayor (David Margulies), forced to rely on the Ghostbusters to save his city, has him bundled off, a pivot from their early humiliations. The finale of Ghostbusters is almost unique in managing to proffer big, special-effects-enabled showmanship whilst maintaining its style of humour, refusing to devolve or divert tonally even as Zuul and Gozer finally arrive, whilst sustaining a self-mocking approach to its own blockbuster pretensions. The crowds hail the team’s arrival at the site of battle just like the viewing audience, and then Reitman cuts to the boys laboriously climbing up the stairs within Sandor’s building.

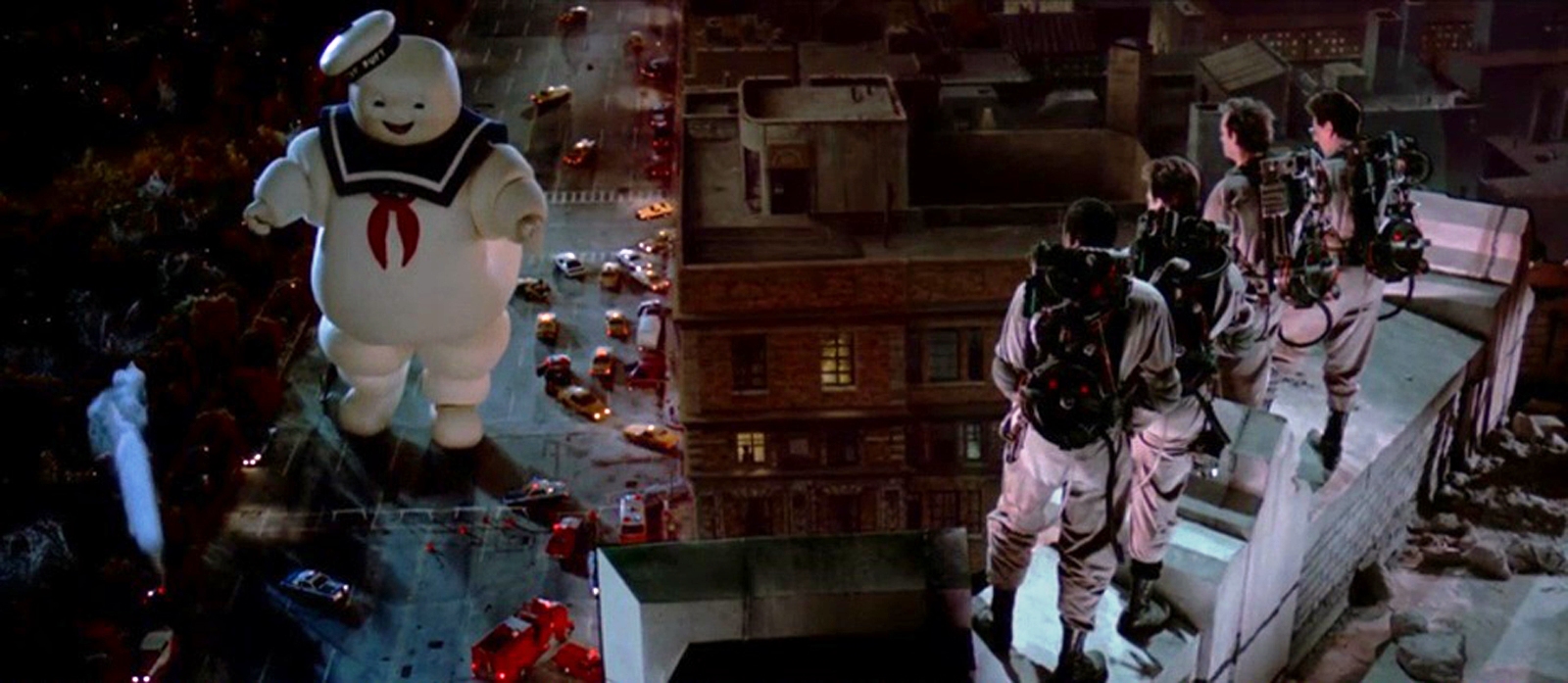

Aptly, Gozer manifests as the most alien and threatening thing a team of ’80s working stiffs could imagine—an imperiously cocaine-chic, Eurotrash fashion model. Seeming to have stepped out of some particularly wacky Vanity Fair cover shoot, she asks the team if they’re gods, which, of course, they patently are not, not even by mere New York standards. She then tries to kill them with bolts of lightning, inspiring Winston’s inimitable advice, “If somebody asks you if you’re a god, you say YES!” Gozer’s otherworldly palace is a glorious Bauhaus hallucination of the swank nightspot you’re not cool enough or rich enough to get into. The boys are bidden to choose the form their destroyer will take, and Ray, unable to make his mind a blank to avoid making a choice, chooses the most harmless, childish emblem he can, resulting in a 200-foot-tall advertising mascot, the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man, stomping his way in Godzilla-like glory down Broadway.

This touch could have tilted the film towards silliness, and yet it works perfectly, as it both combines and crowns the twinned streams of plot and comedy. Of course, even faced with imminent apocalypse, the boys’ ingenuity isn’t exhausted, and they step up to the challenge of shutting Gozer’s portal at the near-inevitable cost of their lives with a last show of stoic grace that’s quite moving in an almost throwaway fashion without losing the qualities that define them: “I love this plan, and I’m excited to be a part of it!” Peter cries with both genuine bravado and purest sarcasm. And that’s the deepest, most admirable quality of Ghostbusters, that it keeps its wit and humanity in focus even in the most absurd and extreme of circumstances.

Rod – You’ve outdone yourself with this one. You are so astute about the commercialism in this film, something that seems obvious in hindsight but that might not have occurred to anyone with the same kind of sarcastic brilliance as it did to this smart creative team. I love how you pinpoint Winston’s contribution to the final team, how it zeroed in on the coming collision of science and religion. That an African American was the harbinger of spiritual doom seems fitting, as it was not so apparent how white America stood on religious issues at this point in time. I, like so many others, loved this film and appreciate that it was given high production values to really bring the vision to life. Weaver was rather ill-served by Hollywood after this film (Half Moon Street, 9 to 5), but at least she’ll always be the Keymaster.

LikeLike

Yes, this is unprecedented scholarship for a film such as this, and I say that is the most positive sense. The film has maintained its popularity and some of the phrases of course have become a part of the culture. This is a very big favorite in my own house, and has been viewed by the residents more times than I can remember. It does seem miraculous that this kind of film averted disaster by crashing into juvenile silliness, but you so very well delineate.

I will only add the orchestral score by my favorite film composer of all-time, Elmer Bernstein, as an integral part of this against-all-odds winning melting pot.

LikeLike

As with so many of your essays, this makes me dang thirsty to watch the movie in its entirety for the hundredth time. Your descriptions of the characters are the exact adult verbiage for what I could never explain as a kid – and they’re perfectly on the money. Likewise, the smartly crafted tension among the three (then four) Ghostbusters, in terms of their types, is something I had honestly never thought of, but you nail it – and the comparisons make me like them all the more. I realized as I read this that I had, as a kind of habit really, a knee-jerk “favorite” in Venkman simply because he’s Bill Murray, but I have to say that now, given the prompt of your essay, if I had to choose who to save from a giant marshmallow man, I’m just not sure anymore. Reminds me, one note you may have implied without actually saying it (or did I miss it) is that the Marshmallow Man is the perfect extension of the movie’s metal-strong throughline of the 80s bending toward crass commercialism – eventually the ethos of the bargain comes back too huge to handle and may just kill you. Also, a nod toward Bernstein’s music as a perfect match to the “bigness” of the effects and visual scope. Might be his best work since… wait, he did Robot Monster??! And, from a movie that has to be in the top five most quotable movies ever (comedy or otherwise), that last sequence has my favorite: Egon’s beautiful toss-off, “I’m frightened beyond the capacity for rational thought” – a line quoted by me so many times, it may wind up on my headstone. This movie is wrapped so tightly inside every cell in my body, it’s near-impossible to see it objectively – you’ve helped me take a step back and appreciate it anew. Well done.

I see that Sam beat me to the Bernstein punch. Good call, Sam!

LikeLike

Mare, Sam, Robert, thanks for speaking up here.

Mare, I love your comments about Winston’s spirituality and its presentation of both foreboding but also a deeper perspective on things. One of my favourite, subtler satirical swipes in the film, which I’d’ve mentioned but for space, is when the Mayor talks to the Cardinal from the Catholic Church, which, he informs us, won’t take any position on the freakish events consuming the city. This is such a casual but exact jab at the establishment complacency of his church, that it can’t even recognise something within its theoretical provenance anymore. This definitely feeds into the notion of a schismatic world view you mention. I do have to disagree a bit about Weaver’s career after this; I think you mean Working Girl rather than 9 to 5, and I haven’t seen that but she got an Oscar nomination for it, and her big career moments of Aliens and Gorillas in the Mist (two more Oscar noms) happened after this too; in fact I think this movie provided a bridge between her fantastic image after Alien and more earthly roles.

Sam, your stories of the film’s popularity in your household reminds me of my own youth, when I went with some extended family for a seaside holiday and we finished up watching this once a day for a week. This was the boys’ choice of video. I can’t remember what the girls rented the second week, only that we didn’t like it.

Bernstein’s score was really overshadowed by the title song and the other pop songs on the soundtrack (which are by and large really good – “Magic” in particular is a fascinating listen in total, whilst of course the theme song still spells party to a lot of people) but it is a superb piece of work, moving swiftly and easily between grandeur, menace, playfulness, and ironic heroism; he never has trouble understanding the film’s tonal shifts and indeed communicates them deftly to the audience. As for what was his best score prior to this, well, his work on An American Werewolf in London is great (although similarly overshadowed by pop songs) was great (and did similar genre-bridging work), but prior to that I might have to go back to The Bridge at Remagen.

Rob, Venkman is indeed a more abrasive character than he seems to kids who grew up charmed by Murray and delighting in his brattiness. On the other hand, that’s what I love about him; I wish more movie heroes were as eccentric, as sarcastic about the absurdities surrounding them, in a manner that’s free of any hint of meta, referential humour. By contrast, he gets too cute in the sequel. It’s kind of odd that Aykroyd wrote himself by comparison the most restrained character to play, and yet Ray never fades into the background. Rob, I admit, whilst I did think of the link between Mr Stay Puft and the gags on commerce, I didn’t actually comment on it; it is nonetheless as you say a perfect consummation of that element. And, what’s more, it’s fascinating how powerful the evident nostalgia, the longing for youth, Ray expresses as he explains his choice; all through the movie he hints at a rueing of adulthood and regret for losing his childhood (the way he complains about the mortgage on his house feeds into this too, as does his bitter quip about them expecting results in the private sector. This in turn connects to the film in total: it pulls down the dull world and makes everyone feel like a kid again.

I think I’ll include here the snippet I wrote about the sequel cut from this piece, as unofficial coda:

LikeLike

Rod – You’re quite right – it was Working Girl, and I am flabbergasted that she was nominated for that. The character is pure corporate caricature that required little from her to be as one-dimensional as possible. I don’t think she got a good comedic role until Galaxy Quest in 1999. Of course, she has created some indelible roles, for example in The Ice Storm, but the 80s were not her most distinguished decade.

LikeLike

The following is half-formed, at best, just me trying to get even more underneath the appeal of this movie. Every time I watch it, I’m impressed with its “bigness”. It’s part of the ongoing appeal to me, and it has a lot to do with everything that you outline above, but also to do with the decision they must have made at some point to approach it like they were shooting an action movie. Comedies had the “big” treatment before this of course, but “1941” still has that muted (is that the right word) tone that says 70s and “The Blues Brothers” is, for my money, only successfully “big” in spots, namely (and obviously) the final half hour’s wildly ratcheted-up chase scene, but that movie suffers for me in the pacing department for most of the movie up to that point. Only Ghostbusters (at this point, but are there others? I guess “48 Hours” – but then it’s intentionally action before it’s intentionally comedy) has everything smartly clicking into the “big” groove from the first shots until the last, never letting up with SOMETHING funny-big, interesting-big, or scary-big at every moment. Lenses, angles, locations, scope (e.g. their rising-celebrity montage)… it all works to keep it BIG. And I love that. Maybe it’s passe since so many movies from that pocket of the 80s and onward had that as well, genre notwithstanding, when they didn’t have to. I’m thinking of one I saw for the first time the other night, Flashdance. NOT a good movie, so choppy (and not artistically choppy, like an intentional bend toward music videos, but just bad storytelling) – but it’s a BIG looking small story, care of the Simpson-Bruckheimer sensibility. It’s a girl-makes-good dance movie that looks frame-for-frame like an action movie. One wonders, why? Then the answer, at least partially, is that well, it’s about the only thing that kept me watching it. Forgive the ramble, I’ve thought about this for years, vis-a-vis my love for this movie, but never expressed it in any way, and barely have here. Help me make sense or this, Rod, you’re my only hope.

LikeLike

Gosh after reading not just the review but the comments as well I can only utter the phrase… ecstatically exhausted!! Yes, of course, Rod you outdid anything I’ve ever read or been part of discussions on the subject…which is to be expected. But the rest of you guys have been inspired!! You tear at that carcase leaving barely the bones to be examined by anyone else, which is fine by me. I’ll merely reiterate what was spoken back there in the volumes preceding me…….I’ll watch it again soon, with new eyes!

LikeLike

I’d like to add a correction to the otherwise splendid article: Harold Ramis’ directorial debut was not “Groundhog Day” in 1993, it was in fact, Caddyshack in 1980.

Also escaping me for some odd reason for all these years is that he directed “National Lampoon’s Vacation”(1983), which is an astounding oversight when you think about it.

He left an amazing amount of work; R.I.P. Harold Ramis.

LikeLike

Sorry, guys, for taking so long to respond here. It’s been a rough couple of weeks. Including the fact that this became an accidental memorial piece for Harold Ramis. I’m truly glad I was able to celebrate one aspect of his talent before he passed away.

Robert, I know what you’re talking about with that sense of scale. As deflationary as a lot of the humour is, the film’s style works consciously against that, refusing to be scaled down. It takes its conceit seriously and plays as epic even in contradiction to its comic approach. That was a rare and original mix, although not entirely unprecedented: the two Bob Hope films I mention above play, when he’s not making jokes, as fairly straight, pungently atmospheric horror films, and Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers has a weird, discursive attitude to its blend of genres: the gags are satirical, but the settings, mood, and story cues are all played perfectly straight and in some ways makes for a weirder and more discomforting mixture than an ordinary horror film. Here Reitman and his crew seek consciously to create a grandiose work, offering imagery which wouldn’t be out of place in a less ironic Spielberg FX epic. I think one connecting aspect of what you’re speaking about here in relation with Flashdance is the degree to which both films reject the naturalism of the late ‘60s and ‘70s as a key to their style. Flashdance was a huge hit precisely because it took that very basic plot and subjected it to a level of stylisation that had occurred only in advertising. Just two years before Fame married a touch of slickness to what was otherwise a very ‘70s looking and sounding film, with the emphasis on gritty environs and new wave shooting styles. Suddenly, with Flashdance, the ‘80s has arrived, and it’s basically a mix of music video and advertising tricks – flash edits, backlighting and diffused source lighting, dance performances constructed with multiple fill-ins for the lead and cutting, etc etc. Ghostbusters similarly contrasts what a ‘70s version might’ve looked like. Indeed, the Larry Storch show that became the object of some legal conflict with this one, might be an example there, with more self-conscious wackiness – a gorilla! A refurbished ‘20s car as their batmobile! Ghostbusters is never less than aware of its own deliberate ironies, but is also determined not to be downgraded to wacky distraction in the new age of the blockbuster.

Shane: thanks for that. That’s what makes writing these rewarding.

Kelly: urgh, man, I’ve got stop writing these things from memory. Thanks for the heads-up there.

LikeLike

Rod, that paragraph soothed my soul. Exactly the clarity I needed and right on the money.

Re: the rejection of naturalism in Flashdance. I watched Fame (’80), Flashdance (’83) and Footloose (’84) in one three day stretch last month. Fascinating to see the progression from earthy, still-like-the-70s vibe to the all out grab for gravitas via lighting and cutting to the unexpectedly smooth mix of both. Not that the non-dancing parts of Footloose felt like the 70s, but they at least went for real, rooted emotion, esp in the Lithgow arc (I expected bombastic preacher from start to finish, but Lithgow played him as a broken man who’s slowly revealed and changed and possibly the only good reason to recommend the movie). That said, if anything, most of Footloose felt like if John Hughes wrote a dance movie.

But I’m way off topic now.

LikeLike

Excellent look at a film that’s been written about to death. You write:

“The Ghostbusters are, indeed, very much like the Animal House or Meatballs characters a few years older and scarcely wiser, now growing off the body of academic culture like warts, but faced finally with sink-or-swim survival in the world of ’80s yuppiedom.”

This is a fantastic observation and nails exactly what this film is all about. You can see Murray, et al building towards a film like this with the stuff like STRIPES, but I would argue that it reaches its zenith with GHOSTBUSTERS where former counter-culture heroes become the establishment, esp. with the massive commercial success of this film, which is probably one of the reasons why the sequel was such a crushing disappointment. These guys were no longer the cocky underdogs, but trying to make lightning strike twice and failing.

It is interesting to see where the career paths of Aykroyd, Murray and Ramis diverged after this film with the Aykroyd becoming less and less relevant, Murray developing a more soulful, deeper set of skills thanks to collaborating with the likes of Wes Anderson, and Ramis increasingly working behind the camera.

LikeLike

I’m filled with admiration, Rod. My one (slight) complaint is that, in talking about composer Elmer Bernstein’s contribution, you don’t mention his score for AIRPLANE! (1980). That score, for me, has always a touchstone example of funny-yet-serious writing.

LikeLike

Hi Chris and thanks. Well, given one day I hope to do a full review of Airplane!, I expect I’ll be able to expound more fully on that great score. Not that long ago I was reading an interview with ZAZ and they talked about how his work on the film suddenly turned him from that guy who scored all those old epics to the guy everyone wanted to do their comedy. So I expect his work here directly stemmed from that.

LikeLike