.

Director/Coscreenwriter: Sergio Leone

By Roderick Heath

For Sergio Leone, making Once Upon a Time in America was a 15-year labour that consumed the bulk of his directorial career. By the mid-1970s, Leone seemed to be washed up. The genre he had done so much to codify and popularise, the spaghetti western, had burnt out. Leone’s tilt at making a defining western saga, Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), was mutilated and dismissed in the US, and Duck, You Sucker (1972) was similarly lost in the shuffle. Although he continued to produce odd projects and stepped in to help direct some without credit throughout the ’70s, Leone was left perched between worlds. He rejected advances from Paramount Pictures to direct The Godfather (1972), as he was fascinated instead by a purportedly autobiographical novel called The Hoods by former gangster Harry Goldberg, who published under the name Harry Grey. Leone finally put together a big $30 million budget. His ambition seemed to pay off as the 4.5-hour epic earned a standing ovation upon its premiere at Cannes. Triumph quickly curdled, however, for such expansive vision was conspicuously out of favour. A hacked-down version of the film released in the U.S. was a colossal flop, and the calamity on top of an arduous shoot helped kill Leone 5 years later. The 229-minute European cut, however, retained a strong reputation for those who could see it, as I first did, on a brick-thick VHS set.

Aside from its length, Leone’s film was always bound to be a challenging and commercially tricky proposition, as Leone created a deeply ambiguous work, an apogee of the director’s unique temperament. Contradiction was Leone’s defining quality. A high stylist with a gift for lowdown art. A realist with a love of mythology. A romantic with a fetish for brute violence and sexuality. An Italian with a predilection for American pop culture and a gift for creating synergy between the spacious, aestheticized approach of European film and the gritty sturdiness of American argot and actors. A revisionist and Socialist-tinted historian, picking at the scabs of worldly motives, always looking for the carnal and corruptible underpinnings of human impulses, and yet conjuring dreamlike, mythopoeic visions of that history shot through with quixotic longing and melancholy. Once Upon a Time in America is a film where the audience is faced with mirroring ironies that fold time and tale back in on itself.

Leone employed seven screenwriters to build upon his ideas, including an uncredited Ernesto Gastaldi and snappy English dialogue by Stuart Kaminsky, and yet each touch was subsumed into Leone’s, as the film is more visual than verbal. It also both extends and contrasts the methods of Leone’s westerns. The long, elliptical, carefully rhythmic and internally rhyming structuring of Leone’s direction, as small plays of character and power and build-ups to violence are detailed with nerveless intensity, were retained. But whereas Leone’s westerns were defined by space, both in the environs of the open range, and crisp widescreen compositions based on horizontal lines, …In America is dense and baroque, the blasted colours and sunstruck brightness swapped for saturated tones, deep-etched darks and opiated atmospherics.

…In America has been characterised by some as one long drug dream, taking place in the mind of antihero David “Noodles” Aaronson (Robert De Niro) as he lies in an opium den. The movie starts there and finishes there, moving in an Ouroboros sort of pattern. Noodles has retreated to the den behind a Chinese shadow-puppet theatre to forget the consequences of the pivotal act of his life, an act that’s communicated in impressionistic fragments of sound and vision. The first scene of the film depicts his girlfriend Eve (Darlanne Fluegel) being shot dead in their apartment by gunmen on the hunt for him, with the strains of Kate Smith’s operatic take on “God Bless America” echoing in the background. Noodles’ friend, restaurateur and bar owner Fat Moe Gelly (Larry Rapp), is beaten to a bloody pulp by the same mob enforcers until he gives them Noodles’ location. A telephone rings like a jackhammer, burrowing into Noodle’s consciousness through the blur of the drug, conflating a call warning Noodles to flee, and, in his dazed reveries, a phone call he seems to have made to a policeman and the ringing bell of a fire truck at the remembered scene of a conflagration where corpses are laid out, variously scorched and bullet-riddled: Noodle’s pals and partners in crime Max Bercovicz (James Woods), Patsy Goldberg (James Hayden), and Cockeye Stein (William Forsythe), killed, it seems, by some connivance of Noodles’.

This opening manages at once to be allusive and close to psychedelic, whilst intelligibly suggesting both the taunting mysteries of the oncoming drama and the urgency of the immediate danger to Noodles, who has to flee the den and save Moe. This he does, in a scene that recalls the opening of Once Upon a Time in the West. Where that film had a windmill and a steam train on a flat plain, here there’s an elevator and interior heights, appropriate for the vertiginous moral chasms and landscape of the city. The elevator works laboriously, motor grinding and mechanisms shaking, to the floor where Moe is laid out like a carcass and a waiting assassin patiently awaits its passenger to alight. Instead, a bullet explodes out his forehead, fired by Noodles, who took the stairs. As well as being a quintessential Leone moment of surprise violence, Noodles’ wiliness is revealed here, a gift the film recapitulates many times, if so often in counterpoint with his endless capacity for self-sabotage.

A talismanic key is taken from Moe’s grandfather clock, a key that fits a locker in Grand Central Station, but to Noodles’ evident shock and disappointment, the suitcase within only contains a bundle of newspapers instead of the expected fortune. Noodles has no choice but to keep running from the vengeance he has set in motion. He steps out of the frame, the camera zeroes in on an art deco poster for Coney Island and a wall mirror. Noodles re-enters the shot, reflected in the mirror, balding, doleful, and tense. The artwork is now a pop art mural, a version of “Yesterday” rises to displace “Night and Day” on sound, and without a line of dialogue, we know Noodles has returned to New York in the late 1960s.

This cunning leap forward touches on one essential aspect of …In America, which is as much about time and what it does to people and what they do to themselves in the eye of it, as it is about individual circumstances. It’s also one of the greatest explorations of the transporting intensity of remembering. Leone and ever-attuned composer Ennio Morricone even twist the potentially cheesy idea of using “Yesterday” as a leitmotif for aging regret to work for them by pushing it to a limit with a muzak-flavoured cover: nostalgia is another pop value. Noodles and Moe meet again, tired and on the wane, defined by a past that went magnificently and seemingly irreparably wrong. Moe’s bar is an islet of the past in a former Jewish neighbourhood, now filled with the new wave of Puerto Rican immigrants. Moe certainly didn’t pilfer the million dollars in the locker, Noodles now sees, and he explains the ominous yet seemingly casual missive that’s brought him back to New York, a letter that confirms someone knows where he’s been hiding and has now summoned him back for a reckoning. Longing for a chance to repair the past and pining for the flare of youth’s energy and vision transfigures Noodles. But he was not a good man, not even one ennobled by the Corleones’ familial ethos. Rather Noodles was, as the idol of his life, Moe’s sister Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern), once diagnosed, a guy always doomed to be a two-bit punk. Noodles’ return home sees objects take on transformative power, recalling distant times and people in a manner Leone correlates with cinema itself: in the back of Moe’s bar is a peephole, and looking through it like a movie audience conjures a young Deborah (Jennifer Connolly) as a vision of youth’s hope.

That youth is revealed as hardly an idyll, however, as Noodles and his pubescent pals were dirty-minded, fun-loving, budding criminals. To make money off local standover man Bugsy (James Russo), Noodles (played young by Scott Tiler), Patsy (Brian Bloom), Cockeye (Adrian Curran), and Dominic (Noah Moazezi), burn down a newspaper stand. They also rob drunks and blackmail an obnoxious cop (Richard Foronjy) after they photograph him having sex with underaged sexpot Peggy (Julie Cohen). Leone’s young imps are little pishers, glimpsed squirting lighter fluid as if they’re pissing on the newspapers. The boys encounter Max (Rusty Jacobs), a junkman’s son who foils one of their criminal enterprises with cheeky humour and then joins them. Success continually raises the stakes for the boys’ misadventures: gaining control over the cop places them in the path of Bugsy, who has Noodles and Max beaten up. When Noodles and his pals outmanoeuvre Bugsy in ingratiating themselves with the mafia, the older punk sets after them with a gun.

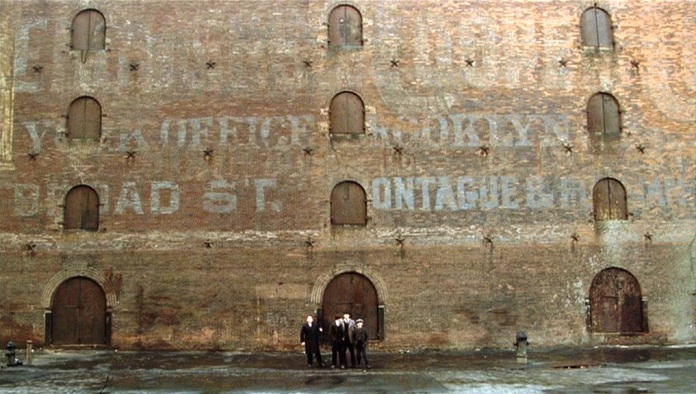

These ’20s sequences are majestic in their blend of the hazy immigrant remembrance that was popular in the newly ethnic-conscious and historically attuned American cinema (The Godfather Part II, 1974; Hester Street, 1975; Ragtime, 1981), but far outstripping most for evocativeness and exactitude of milieu—Leone’s period worlds are characters in themselves. One of his keenest gifts lay in creating organic milieus in particular places where social forces are in constructive flux. Leone’s crack team of filmmakers—cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, editor Nino Baragli, art director Carlo Simi, costumer Gabriella Cespucci—helped to make his old New York a place of dirty wildernesses of brick and cobble where the criminal lads dash and dance like Our Gang turning into Dead End Kids. Rooftop empires of bird shit, flapping laundry, and illicit sex and empire-planning. Harbours flooded by fog, zones of mystery and adventure. Above all, nascent industrial might symbolised by the Manhattan Bridge, like living in the shadow of a pyramid, the New World’s expression of communal power and hubristic desire. The neighbourhood around Moe’s place evolves in obedience to the zeitgeist. The old kosher restaurant run by the Gellys where young Moe (Mike Monetti) labours is a popular community crossroads. It gives way to a speakeasy, popular with a panoply of the urban melting pot, housing both underworld and elite. Finally, it becomes the clapped out, run-of-the-mill bar where Moe has to pay protection to a Puerto Rican standover man. When Noodles is fatefully carted off to a juvenile prison, both the prison and the opposing warehouse wall against which his friends range to see him swallowed by the beast emphasises the impersonal scale and fetid, rotting atmosphere of the urban landscape in a fashion that feels the oncoming age of oppression.

The very American tale of the immigrant experience, defined by the simultaneous, wrenching, gravitational fields of ethnic community and eruptive New World mores (young Noodles refuses to go home because “my old man’s praying and my old lady’s crying and the light’s turned off”), is crossbred with the Italian cinematic tradition for looking back in pained wistfulness at the birth pangs of modernity in films as diverse as The Leopard (1963), The Voyage (1974), and 1900 (1976). There’s also the equally Italian delight in describing the raw side of entering adulthood. The young hoods are obsessed with sex, whilst wrestling angrily with their weaknesses and deeper desires. Although the protagonists of …In America are unusual in the ranks of screen hoods for being Jewish, they’re exceedingly Italian in spirit, calling to mind the libido-addled adolescents of Fellini’s 8½ (1963) and Amarcord (1973). There is also, of course, deliberate recapitulation of classic movie themes, specifically, the gangster film, laced with references. The rise-and-fall stories of Little Caesar (1930) and Scarface (1931); the immigrant angst and youth-to-nefarious age drama of The Public Enemy (1931); and remixes of those themes in the tempted street kids of Angels with Dirty Faces (1937) and the generation-tracing arc of The Roaring Twenties (1939). Also, the galvanic punch and sociological notation of Don Siegel, Roger Corman, and Sam Fuller in the ’50s and ’60s, and the political awareness and epic tone of The Godfather. One original aspect of the story, anticipating Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), is the way its narrative centres on a character who could be perceived as peripheral, even a loser. Whereas James Cagney’s and Paul Muni’s gangsters always fell eventually but became colossal in their defiance or their tragic qualities, Noodles becomes not a fallen warrior, cautionary example, criminal overlord, or even really a proper antihero. Rather, he remains something of a fool of fortune doomed to keep losing great chunks of his life to his antics and poor judgement.

Youth is brought to an end through a series of rolling events, and indeed all three epochs described in the film detail long plot arcs dotted with vignettes and climaxing in dramatic severances. The greatest moment of the lads’ youth comes when they convince a mafia overlord to try their invention, involving flotation balloons and counterweights of salt, which can refloat cargos of liquor dumped in the river to avoid patrols. Waiting on a boat in the harbour in a dreamy mist that slowly unpeels over a grimy industrial waterway, the boys see their invention work and celebrate, with Max and Noodles falling overboard: Max plays a prank on Noodles, pretending to drown, before reappearing in the boat, flashing his mocking grin. Much later, Noodles plays the same gag on Max. The two friends, closer than brothers, also constantly try to get one over on each other, treating life almost like a huge practical joke. The folie à deux aspect of their friendship defines the entire narrative. Deborah mockingly describes Max as Noodles’ mother, constantly calling him, but for criminal hijinks. Max first appears on a garbage cart, and steals a watch from a drunk the others wanted to roll, motifs that double and reverse in the finale. Bugs shoots Dominic, who dies with pathos in Noodles’ arms, his felling filmed in slow motion, severing youth from adulthood. Noodles, in a lunatic fury, knifes to death both Bugsy and a cop who tries to intervene, and is imprisoned. He’s released years later as an adult, when Max and the others have become successful bootleggers and entrepreneurial criminals.

Max greets Noodles upon release with a present that combines Leone’s love of bawdy sexuality and morbid humour: Max has a hooker (Ann Neville) laid out like a corpse, pretending to be dead, only to drag Noodles in to prove they’re both very much alive. As the famous quote from …In the West says, Leone’s heroes have “something to do with death,” yet sex and death are constantly correlated with insistent, Freudian power, particularly in this film, where both impulses are seen as the logical extremes of life, whilst most nebulous needs, like love and power, have a grip of religious insubstantiality to them. Whereas love was something Leone’s gunslingers spurned in pursuit of revenge, or had lost and spurred that revenge, Noodles is fatally split by his base instincts and higher aspirations. Carnality is its own strength: when he’s returned to Moe’s, Noodles encounters an older Peggy (Amy Ryder) who’s now a rotund madam-cum-earth mother who sells it profitably “by the pound.” Reunited with his pals, Noodles is brought in on a heist job shopped out to them by made man Frankie Manoldi (Joe Pesci) and his acquaintance Joe Minaldi (Burt Young), who’s got wind of a lucrative diamond shipment he wants them to rob. This turns out to be a double-cross, as the gang’s really been hired to kill Minaldi, and take the diamonds as pay by Manoldi.

Young’s hilariously grotesque cameo as a kind of simian throwback jammed into a suit, telling the story of how he got the tip-off about the diamonds via an anecdote involving insuring his penis, calls back to the shambling, ill-shaven untermenschen that dogged the heroes of Leone’s westerns. Those heroes are by contrast pre-modern but not uncivilised men who seem to share the distant bloodlines of Titans in their gifts that elevate above the common run. The double-cross assassination takes place in another peerlessly atmospheric setting, a foggy canalside littered with beached steamboats and industrial detritus, and plays out with deliriously intense staging. Cockeye shoots Minaldi point-blank through his jeweller’s glass, the gang rake his car with a tommy gun, and Noodles chases an escapee into an eiderdown factory, where he catches his prey and guns him down in a shower of whirling feathers. Noodles performs well, proving he’s still a man of action, but is irritated at having not been told what was going down. He vents his irritation at Max and the others with loopy humour by driving their car off a pier, suggesting that even now, with their extremely grown-up sex and violence, they’re still kids delighting in mayhem and tomfoolery. An aspect of this extends through a ribald subplot: during the robbery of the diamonds, Noodles was pulled into a play-act rape of the jeweller’s secretary, Carol (Tuesday Weld), actually the inside snout who tipped off Minaldi and a deeply kinky broad who gets off on illicit thrills. When she coincidentally turns up at Moe’s as a customer, the gang greet her wearing the handkerchief masks they used in the robbery, with their dicks out, so she can pick out her prior acquaintance. But Carol picks Max, and becomes his girlfriend.

The more “elevated” influence on Leone’s tale was The Great Gatsby, which informs the longing quality of Noodles’ attraction to Deborah and all that she represents, in youth, as a creature of grace and purity in a mucky world, and in his manhood, as a woman going places in the world legitimately. Unlike Daisy Buchanan, however, who was a gossamer idyll formed by an elusive precinct of aspiration, Deborah actively constructs herself, knowing full well the world she lives in and the nature of Noodles. She puts on airs and wheedles her way out of chores by dint of her exceptionalism, as she’s trained in arts that may take her places, including feminine arts full of mystique and irritating power over Noodles. The childhood friends who take different roads is another old motif of the gangster film (Little Caesar, Manhattan Melodrama, Angels with Dirty Faces) crossbred here with romantic longing, but developed in highly unexpected ways because one of Leone’s darkest themes here is betrayal and the damage people who love each other can do. One of Deborah’s fateful acts, locking Noodles out of the restaurant and refusing to answer his cries for help after he and Max are beaten bloody by enemies, suggests that Noodles will always be on the outside, calling for Deborah, and also informs his later act of brutal revenge on her, inextricable from his erotic and emotional obsession. The film’s apogee of romanticism depicts Noodles trying finally to consummate his love for Deborah with his ill-gotten fortune, taking over an off-season hotel for the night in a show of spectacular courtly advance shot through with intimations of grandeur and sadness; this scene captures the essence of Fitzgerald’s book better than any straight adaptation has so far achieved.

Yet it also provokes and feeds into Leone’s own Janus-faced sensibility, as Deborah maintains her focus and tells Noodles she’s leaving for Hollywood in the morning. He, smouldering with anger whilst they’re being driven back to the city, viciously and punitively rapes Deborah on the backseat until the chauffeur pulls over and puts an end to it. A supremely disorienting and ugly scene (though fascinatingly undercut by the chauffeur’s agency, as he even refuses Noodles’ money; in most melodramas with a crime of this sort, the functionary would be assumed to be a moral null), is one of Leone’s singular accomplishments, as it so utterly debases the usual core of sentimentality found in the gangster film, forcing a radical audience reorientation of where its sympathies lie. Early in the film, Noodles’ hunters had shot Eve, Deborah’s worldly substitute, and, with electric provocation, one tweaked a society lush’s nipple in the opium den with his pistol. Sexual violence adds an uneasy, potent undercurrent to the film as a whole. With Noodles’ assault on Deborah, it becomes clear that Noodles’ lifestyle and milieu, far from being redeemed by Deborah, has instead poisoned him, his expectations of women and life in general. Indeed, what was pseudocomic and anticipatory in Noodles’ and friends earlier sexual encounters with Peggy and Carol becomes appalling.

Leone reaches for and achieves Dostoyevskian stature in his depiction of madly clashing impulses inside characters, as Noodles is at once exposed in his reactive cruelty: he essentially treats Deborah in the same way he did Bugsy, with the blind anger of a kid who feels he’s had something treasured stolen from him. He also defeats himself utterly, and feels immediate, crushing shame, as he watches Deborah leaving for Hollywood on a train the next day, amidst a swirl of steam on the platform, like he’s a phantom his own life, which indeed is what he becomes. There’s a moral precision to this even as Leone largely rejects simple moral readings—all his characters here are cruel to each other on some intimate level, of which physical violence is only one variant. Earlier, young Deborah had charmed Noodles and sustained his fantasies by reading to him from the Song of Solomon, but roughing up the sublime poetic metaphors by comparing the idealised creatures on the page with Noodles, hanging onto her words with increasing torment as she stated “he could never be my beloved.” Deborah’s ironic reading elucidates Leone’s art: alternations between lofty yearnings and expressions of sublime emotions jarringly interpolated with vulgar and cynical sophistication. Equally strong and just as auspicious as Noodles’ crush on Deborah is Noodles’ bromance with Max, whose enticingly wicked grin and humour casts a different spell. Max’s spying curtails Noodles’ one kiss with Deborah just before Bugsy’s beating, signalling Max’s impact on their fate, and also, as later events confirm, exploring the synchronicity of their identities.

Leone’s critical understanding of capitalism threads throughout the film, as it did in …In The West where Frank (Henry Fonda) gazed with admiration and frustration at the apparatus of fiscal power after he has done the work of annihilating the small-time speculator for the profit of the big operator. Here Noodles has the gift for creating and putting over a stratagem, but it takes evolving tycoon Max to utilise them as part of a larger project. One provides the labour and invention, the other exploits. This film deals with characters who are villains in Leone’s other films, though Cockeye, like Harmonica in …In The West, carries an instrument (a piccolo), and Noodles feels the righteous spur to revenge on Bugsy, an urge he will later, importantly, quell and reject. As in Leone’s westerns, community exists, but the heroes do not protect it, exemplify it, or even really blend into it, but are rather cordoned off in a way John Ford only did with final deliberation: when young, the boys are constantly filmed in empty streets at the fringes of activity, or on rooftops, whilst Deborah passes through the midst of crowds, both at one with them but moving against the tides. The beating Noodles and Max receive from Bugsy occurs after the rest of the street has deserted with the residents heading off to the synagogue. Even when Max finds security and insider status under an assumed identity and fortune, he cannot join the crowds in his house, and spies instead on his son as he greets his pretty girlfriend and enjoys all the joys of his aristocratic youth, bought with so much bloodshed and loss.

When Noodles first returns to his old street in 1968 and nears Moe’s, he is confronted by the momentarily surreal sight of a gravestone lifting into the air from behind a brick wall by a front-end loader, as the old immigrant graveyard is being disinterred. The motifs are trebled here, as both the memento mori hanging over Noodles is literalised, the notions that graves are opening and the dead walking is first hinted, and the unavoidable fact of the past being consumed by the present. Later, he finds his friends have been granted an ornate mausoleum, which, a sign says, was paid for by Noodles himself. There he finds another totemic key to the same old locker at the station containing a suitcase full of money: Noodles is being given one last job.

A scandal is playing out on TV with a face Noodles recognises: union boss Jimmy Conway O’Donnell (Treat Williams), who the old gang once saved in their finest deed, supporting striking Teamsters, by using wit as well as weapons to combat a plutocratic manager, his goons, and his pet cop, Chief Vincent Aiello (Danny Aiello). Leone goes to town in a bright, relieving comic movement staged with impudent vivacity to “The Thieving Magpie,” as the gang swap babies in their hospital cribs, including Aiello’s, repeating their earlier act of blackmail to impress a cop. Leone pulls off a mirthful, technically superb overhead shot of a nurse frantically trying to calm the crying babies who have just been swapped, visualising the thematic notion spoken subsequently, that the gang have just played god and reapportioned destinies to each character. As Max says, “We’re better than fate. We give some the good life, give it to others right up the ass.” The gang’s swashbuckling efforts on behalf of the unionist prove they still have emotional ties to the cause of working men. This proves a double-edged sword, as they put O’Donnell in debt to the mafia. Noodles rejects the oncoming age of corporatized criminality, which Max, O’Donnell’s political overlord, and Manoldi begin to build to carry them past the end of Prohibition.

Indeed, the film examines a common point of fascination for modern gangster movies and popular history, digging into the complex relationship between organised labour, organised crime, and progressive politics. There’s the suggestion that in the formation of a new bloc of power out of divergent interests to counter settled oligarchies, helped define modern America. Max, alone amongst the gang, sees the possibilities, and he takes his chance to complete his own version of Deborah’s dream to completely transcend his roots and become a great American. Noodles’ rejection of the combination vision sets in motion Max’s master plan even as he seems to acquiesce, and his plot plays out under the guise of suicidal madness, as he proposes an impossible heist. Rather than let his friend push along with this seemingly mad intention, Noodles then counters with his own calculated betrayal, setting up the gang to be arrested on their last liquor run. But Noodles is absent, knocked out by Max seemingly in an unstable rage, and the story begins to catch up with itself, as the early glimpses of the aftermath of the set-up have already told us how this ended. Or did they?

The return at last to 1968 to play out the final stages, comes with the revelation that not only is Max alive, now known as Bailey, but he has wormed his way into the highest reaches of society and political life and seduced Deborah. This fact revealed to Noodles in his poignant, inevitably tentative reunion with her after a stage performance, or rather when the reunion concludes: Deborah’s face, swathed in stage make-up, is despoiled as she rubs it off, identity seemingly smudged as dimensions of her character Noodles never imagined are opened up. The face of her son (Rusty Jacobs), who arrives whilst they’re talking, instantly rewrites the past—he has Max’s young face, stamped by preppie innocence and confusion. Noodles’ contrition at what he did to Deborah is matched by her and Max’s guilt at having destroyed him to gain their own lives.

“Bailey” and his works are unravelling, however, thanks to the still-lingering ties to O’Donnell and the mob, and the final truth that emerges is that he only delayed, rather than avoided, the same reckoning that Noodles has long since made: finding Max heals rather than hurts Noodles, and he’s revealed in their final exchange as an almost monkish penitent, calmly and sadly refusing Max’s request for a friend to shoot him rather than some anonymous assassin, whilst recalling their shared youth, a time that involved and led to horrible things, and yet was still youth. The ambiguous, even surreal final moments of the film provoke both frustration and wonderment, and yet can be coherently read. Max seems to follow Noodles out from his house only to disappear into a passing, peculiarly menacing garbage truck, evoking one tale about Jimmy Hoffa. But does he kill himself, or is he killed? Either way, he goes out the way he came into Noodles’ life, in the back of a garbage mover, moments after he held up that watch, that talisman of the past.

The final images of the film circle back to the past, then, as Noodles is passed by ghostly, yet rowdy apparitions of parties past, as Jazz Age roadsters tear by, and then Noodles himself, a young man again, crawls into the opium den, returning to where we found him: indeed, did he ever actually leave? Was it all a dream of anticipation, a drug-enabled psychic fit? Or did, as I tend to think, Noodles realise on some level not unlocked until he got high, that Max had faked his death, and the practical joke was ongoing? Of course, Leone designed his narrative carefully to refuse exact explanations or interpretations, as so many of the film’s devices, scenes, and settings have recapitulated the notion that everything finally ends up back where it started.

As ever with a Leone film, the indispensable aesthetic capstone is Ennio Morricone’s scoring, which swings from florid, operatic feeling to jazzy jaunt. Just as Morricone’s scores for the westerns constantly nudged the atmosphere of Leone’s film toward both expressionist weirdness and the cultural gravity of Latin America through his instrumentations, so, too, does his work here, constantly punctuated by panpipes, give the film an exotic, haunted quality, as if ghosts are crowding the margins of the lives on screen. The cast is superlative. De Niro’s turn as Noodles is low-key, and yet represents one of the actor’s best achievements, in how concisely he portrays a man who ages 30-odd years, avoiding all of his familiar actor’s mannerisms whilst conveying deep, if taciturn emotion. By contrast, Woods is electric as Max, a less subtle role but one that requires the dash and indivisible mixture of charm and visceral scorn he’s invested with, whilst Weld is wickedly good as the masochistic, yet somehow dominating Carol. Even with its deliberate mysteries and the elisions, which may finally be partly plugged by longer forthcoming editions, Once Upon a Time in America is a cinematic pinnacle.

I have mixed feelings about Once Upon a Time in America, which I just caught up with in its full version a few years ago. It’s a stunning film of such epic scope and ambition that it must be taken seriously. However, it’s a challenge to wrap my brain around the fact that Leone seems to identify with Noodles and his tendencies towards misogny. When the rape occurs in the back seat, the music undercuts the horror by resembling the sentimental score you’d hear in a much different type of romance. While I expect that’s by design, I don’t get the sense that Leone is truly villifying this act.

While there’s nothing wrong with presenting despicable individuals as the protagonists of a film, the behavior from nearly everyone makes it hard to find a connection with these guys. Henry Hill isn’t a great guy in Goodfellas, but you can identify with him. Noodles is something else entirely.

Excellent job with this piece.

LikeLike

I must point out, Dan, that there is no music accompanying the rape scene, at least not in the prints I’ve seen. The scenes preceding it do feature romantic music, and are indeed entirely romantic as Noodles tries to turn his fantasy into reality. But the rape has no music. Noodles’ fantasy has been mushed and he responds the only way he really knows how, with violence and a childish tantrum. It is, indeed, not villified in the usual way to most melodramatic narratives — Noodles remains the protagonist, his act is shown to hurt him as well as his victim, and it becomes the single worst memory of his life — but one can hardly construe, like anything else in the film, Leone’s recommending it as the perfect end to a great date.

LikeLike

Sorry, I should have been clearer. I re-read my review to make sure my memory was clear, and what I cited was the aftermath of that scene. To me, it still has this mournful feeling like Noodles has lost something. I don’t get the sense that Leone really looks upon him like the villain that he is. It’s just my read and is open to interpretation, but that’s the sense that I got from the scene.

LikeLike

“As ever with a Leone film, the indispensable aesthetic capstone is Ennio Morricone’s scoring, which swings from florid, operatic feeling to jazzy jaunt.”

Indeed, and in fact for me it challenges his spectacular score for ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST as his best achievement ever. The score is operatic, and it’s achingly elegiac, with one of the most extraordinary main themes ever composed. Morricone wisely uses it at varying speeds on a number of instruments, and it gives Leone’s the thematic underpinning he hoped for. You have written a magnum opus on this masterpiece, a film that many seem to take years to fully admire and appreciate. For me it is unquestionably one of the two or three greatest films of the 1980’s. As you say, it’s a “pinnacle.”

LikeLike

Dan: right, I get you now. However, I’ve already discussed my attitude to this at length in the piece, so I’ll let that stand.

Sam: Yes, one of Morricone’s best (The Mission is another). I understand that Morricone had actually written most of the score in the ’70s when Leone first mooted the project, and undoubtedly this allowed Leone to weave his film around the music with an intricacy that not many film scores can be used with. Ultimately Leone and Morricone will always be joined at the hip as far as viewers are concerned. And it would be a fun thing to argue out what the other two best films of the ’80s are (for me, Ran and Come and See).

LikeLike

Ron, RAN and COME AND SEE are excellent choices if I may say so and both would make my Top 10 of the decade. For me it is so close between several, but I will go with FANNY AND ALEXANDER and CINEMA PARADISO.

LikeLike

Ha, yes, now you’ve actually got me making a list, Sam.

LikeLike

This was a great article! Sergio Leone’s ‘Once Upon a Time in America’ is arguably one of the greatest films ever made; it is art in motion and an absolute masterwork of cinema. It embodies all the ingredients of a supremely grand epic: friendship, love, loyalty, betrayal, the passage of time and the mystery of memory, among many other themes, that captivate the viewer and draw them into the film’s surrealistic world.

I created the following video tribute to the film which features Scott Tiler Schutzman (who played “Young Noodles”); it’s an interesting promo worth checking out for those who appreciate, understand and value this magnificent film:

Noodles, I slipped…

LikeLike

Loved this movie since 1984.

Burt Young and I chat on line from time to time.

It’s Patsy that shoots Detroit Joe…..NOT Cockeye.

LikeLike