.

.

Director/Coscreenwriter: Neal Israel

By Roderick Heath

I’m sure you can imagine my pride and excitement in being asked to participate in the White Elephant Blogathon. How I’ve longed to be ennobled by this most cherished of institutions for the online film scholar. For this auspicious event, I was, of course, expecting half-fearfully, half-excitedly, the films I would be assigned to watch, wondering what peculiar depth of cinematic atrocity or weird and mysterious lode of forgotten peculiarity might be assigned to me. The first and most interesting-sounding one I was able to obtain from my other choices was the all-but-forgotten 1979 comedy Americathon. Directed by Neal Israel, who had previously made the fairly well-regarded speculative satire about the future of TV, Tunnelvision (1976), Americathon is not a film with a good reputation. In fact, it is considered an absolute abomination. One of my online friends told me it was the first film he ever walked out on—he was 8 years old. But still I could hope that whoever had chosen it for the blogathon wished some attentive and open-minded person could rehabilitate what they felt had been wrongly designated an infamous stinkburger.

.

.

There is perhaps no form of bad film more troubling than the bad comedy. The bad comedy resists the usual dialogue of viewer and filmmaker that other bad movies allow, failings that can make seemingly worthless films fascinating, compelling, or just plain hilarious. When someone makes a bad horror film or scifi film, the viewer has the privilege of enjoying the disparity between intent and result—they can laugh at it. But a bad comedy is bad precisely because you cannot laugh at it. This failure inspires instead a sense of personal desperation. As jokes are mistimed and pratfalls land with a thud, bad comedy shames us. Why? Because it’s so closely related to good comedy. We wince with a sense of recognition at how before we’ve laughed at hoary gags, dusty joke set-ups, try-hard comedians desperate to be liked, and clichéd punchlines. We cringe in perceiving how thin the line is between cheeky deflation and juvenile nastiness, familiar mockery and snide impertinence. The experience stokes the worst possible association for us, making us remember those jokes we’ve told that no one laughed at, and worse, made people snort derisively at our lameness. A bad monster movie inspires a sense of fun, of camaraderie with the filmmakers who couldn’t do that much better than you under the circumstances. A bad drama thrills us with the spectacle of seriousness turned camp, the fine art of portraying raw humanity turned into the kabuki of ham glory-seeking. A bad comedy makes you want to hide from humanity.

And yet Americathon gave me some real laughs.

For about 15 minutes.

.

.

Americathon was adapted from a stage production written by Phil Proctor and Peter Bergman, who had earlier collaborated on the script of Zachariah (1971), a more admired genre mash-up. Americathon has a central comic idea that could have yielded comedic dividends, and fits in quite neatly amongst a mode of screen comedy that was pretty common in the ’70s and early ’80s, a mode that seemed aimed to create the cinematic equivalent of an animated Mort Drucker cartoon, teeming with excess detail in painting vast panoramas of general zaniness. This style required brash and vivid execution, exceptional comic timing, and lashings of satire, cynicism, and a knowing, encompassing attitude to pop culture driven by a freewheeling, carnival-like sense of Americana in fecund decline. This comedy style had roots in disparate influences of ’50s and ’60s hip comedy—MAD magazine, Terry Southern, Lenny Bruce, Gary Trudeau, Richard Lester, student stage revues and improv theatre, Frank Tashlin, Buster Keaton, Luis Buñuel, Woody Allen, Tom Lehrer, Yippie street theatre, Mel Brooks, etc. The great days of this style were certainly not in the past when Americathon was released: Steven Spielberg’s 1941 came out the same year, David and Jerry Zucker and Jim Abrahams’ Airplane! and John Landis’ The Blues Brothers a year later. The fact that a lot of these were made by Jewish filmmakers isn’t coincidental. Jewishness was cool in the ’70s, as if all America had suddenly caught up with the Jewish take on things (that’s director Israel there with the sign in the above picture).

.

.

The quality that makes a film like Airplane! hallowed and one like Americathon dispatched to ignominy is one of those mysteries of culture that if someone could distil and package it, would make them rich beyond Jack Benny’s wildest dreams. Kicking off with one of the jaunty songs provided for the soundtrack by the Beach Boys, Americathon deploys a vision for America’s near-future from a perspective that acutely reflects the worries and fashions of 1979, as a dystopian state is played for mordant humour. Without petrol to run them, cars have become homes, and hero Eric McMerkin (Peter Riegert) sets off to work surrounded by bicyclists and joggers on highways turned into communal tides—only now does it look like a green-left dream come true.

.

.

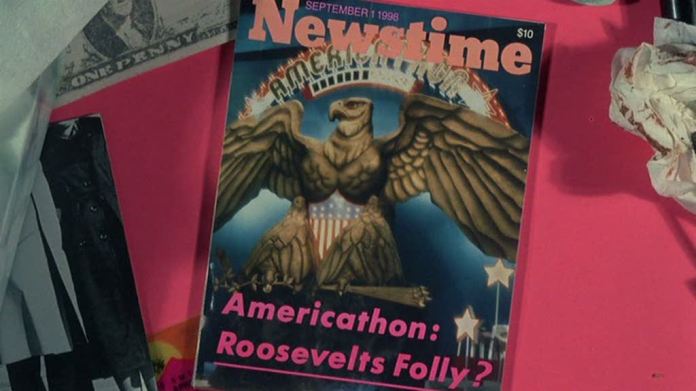

George Carlin narrates the film, supposedly the voice of Eric when he’s older and looking back on these events: Carlin’s wry delivery is very much the reason why I found the early part of the film amusing. Thus, according to Carlin, Jimmy Carter is quickly lynched for giving one of his infamously uninspiring TV speeches, “along with two or three of his snootier cabinet members,” in contemplating yet another energy crisis, and his successor, David Eisenhower (Robert Beer), abandons his post in favour of cavorting with a girlfriend on the beach. The country runs out of petrol in the mid-1980s and money not long thereafter. By 1998, the U.S. is bankrupt and has maxed out its credit from Native American magnate Sam Birdwater (Chief Dan George) to the tune of $400 billion, who is finally calling in the bill.

.

.

The new president has one thing in common with Franklin and Teddy Roosevelt—his name. Chet Roosevelt (John Ritter) is, as Eric tells us, a graduate of “ECT, Scientology, TM, and Primal Grope Therapy,” a blissed-out New Age dim bulb who’s has moved the seat of the presidency into a rented Californian house now referred to as the West White House. Chet’s campaign promise was, “I’m not a schmuck,” but he’s having trouble keeping it. One of Chet’s cabinet members resigns to protest his awful ideas for revenue-raising, like a raffle to sell off public monuments and national treasures, only for his protest to be met with a smarmy kiss-off from Chet. “Fear is just a boogeyman of your mind,” Chet retorts to warnings of the dire situation, “I believe in taking responsibility.”

.

.

Eric, an academic who specialises in understanding TV demographics, is called to the West White House to consult on the raffle, but Eric protests that raffles work badly on TV, comparing it to the effectiveness of telethons. Chet’s bright-eyed girlfriend Lucy Beth (Nancy Morgan) suggests that the government hold exactly that. Chet is, of course, delighted and sets the wheels in motion, giving Eric a cabinet position to run the event he dubs “Americathon.” But Chet’s advisor Vincent Vanderhoff (Fred Willard) tries to sabotage the project at every turn because he’s plotting with ambassadors from the Hebrab Republic, an Arab-Israeli superstate, to take over the foreclosed U.S. Failing that, they have an attack squad ready to wipe out the government leaders.

.

.

Americathon’s foresight is extremely patchy, but often notable, accurately conceiving a future China gone raving capitalist, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the reconstruction of Vietnam as a resort destination, the emergence of vastly wealthy Native Americans, the further debasement of high office by the telegenic, reality TV, aspects of modern environmentalism, and even the once-unthinkable longevity of ’60s rock bands like the Beach Boys. The future China isn’t just capitalistic—it defeated the Soviet Union “in table tennis and a nuclear war,” and has become a fast-food empire. Its most popular export is the Chang Kai Chef Restaurant chain with its biggest seller, the Mao Tse Tongue on Rye. Sam Birdwater’s repeated crying-poor protests that “I have to eat, too!” in apologetically insisting on loan repayment have a ring that’s become ever more familiar in recent years from plutocrats. Nike’s greatest days were still ahead of it, but it was already well known enough for the film to spin a joke around, for Birdwater’s mighty conglomerate is called “National Indian Knitting Enterprises,” specialising in a raft of fashionable industries like running shoes and tracksuits. Whilst the popularity of sportswear and casual clothes hasn’t quite reached the point that Americathon suggests it would, where everyone wears it all the time (even the Americathon host wears a kind of evening dress tracksuit), this is one of the film’s subtler and more pervasive gags. And there are some other, rather less acute anticipations, like its vision of a great Jewish-Islamic imperial power, and its fascinating, very ’70s myopia when it comes to race and sex—the film’s portrayal of a crass and sexist future is inextricable from its own era’s fully subsumed crassness and sexism. Example: the Hebrab Republic is described as having been founded on the recognition of the Jews and Arabs of their common trait—“the hots for anything blonde with a tush.” The film’s vision of debased future TV culture involves a drag queen father (I think that one was ticked off somewhere around 1987).

.

.

Amusingly, Americathon was part-financed by West German investors looking for a tax shelter, which sounds like a plot point from the film, and gives some accidental substance to its theme of the American bodies politic, corporate, and cultural consuming each other to the enrichment of foreigners. One underlying spur for this flight of fancy is a basic, perpetual, peculiarly American anxiety that’s coexisted with the officially optimistic national spirit since the earliest days of the republic—the conviction that it’s all going to fall apart one day, undone by sloth, decadence, and hubris. Here that half-submerged, apocalyptic quality to the American outlook is filtered through common late ’70s concerns, some of them based in quite clear and present realities, like the oil embargoes, energy crises, and the near-bankruptcy of New York, that fed general disillusionment in the wake of Watergate. Post-apocalyptic scifi and futuristic dystopias were common sights on cinema screens in the period; Americathon merely takes the same building blocks and turn them into comedy, in much the same fashion as Dr. Strangelove (1964), to which it pays homage via Eric’s last name, which calls out to Peter Sellers’ President Merkin Muffley. Moreover, the film’s absurdism certainly has likenesses to more recent variations on the same ideas, including Mike Judge’s Idiocracy (2006) and The Simpsons, especially the episode which casts a grown-up Lisa as an assailed President. Americathon then doesn’t lack for a premise with potential.

.

.

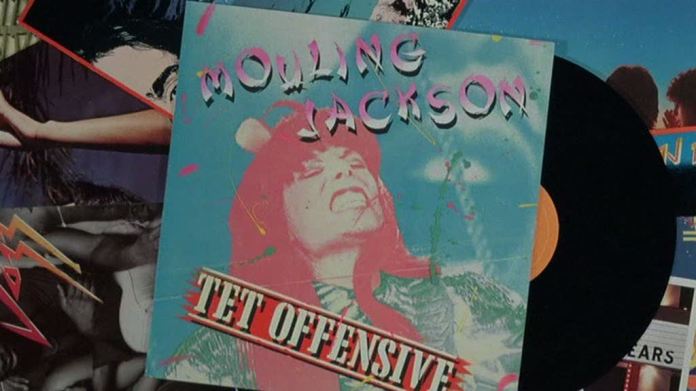

Nor does it lack for conceits that could readily become black comedy gold, like the performance by a superstar thrown up by the newfound fortune and popularity of Vietnam, Mouling Jackson (Zane Buzby), who specialises in songs crammed with sadistic come-ons to Yankee running dogs, performed in front of a colossal Viet Cong recruiting poster. This sequence exemplifies the film’s apparent aspiration to match Mel Brooks’ “Springtime for Hitler” sequence in The Producers (1967) for transcendently provocative bad taste, or a monument to insta-camp as aesthetic value like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975). However, even early Brooks had more directorial skill for that sort of thing than Israel, whose TV sketch technique exacerbates the already lingering structural weaknesses apparent in the slipshod and unfinished transposition from the stage. The songs, which I presume are also imported from the stage version, are charmless. One reason the “Springtime for Hitler” or “Time Walk” episodes in their respective films work well is because they’re great tunes, whilst the songs in Americathon are third-rate pastiche. Vanderhoff ensures that the only acts Eric is supposedly allowed to put on stage are terrible—ancient vaudevillians, most of them ventriloquists. So not only are we facing unfunny comedy in these stretches, we’re also dealing with unfunny comedy about unfunny comedy.

.

.

Americathon’s narrative is supposed to spin out of control along with television programming as it reaches unforeseen levels of grotesquery once Eric, allowed by Chet to slip Vanderhoff’s leash, starts going for the jugular with ever more outlandish, attention-getting acts, debasing the audience even as it saves their country. But the potency here is frittered away even in the film’s already curtailed running time. Any real telethon contains more moments of lethal smarm, dropped guards, self-congratulation, exposed pathos, performative desperation, and self-satire than this film manages. Nor does it make much sense that such an outrageous and popular foreign act as Mouling is booked when the rest of the bill is supposed to be mind-numbing slop. Whilst Israel is happy enough with the free-roaming, vignette-laden silliness of the early scenes, enjoying regulation ’70s jokes like a bicycle ridden by a quartet of nuns, his capacity to film performance is atrocious, missing all the details provided by the choreographers by constantly having his camera or edits in the wrong place, as if someone has half-heartedly filmed a live stage performance. The film as a whole has a blank, dull, cluttered look, one that exemplifies the mercenary quality of lesser ’70s filmmaking, an aspect that accords well with the air of glorified television much of it has. The cinematographer was Gerald Hirschfeld, who did such a good job shooting Young Frankenstein (1974) that for a moment, Mel Brooks looked like a film aesthete. Here, Hirschfeld doesn’t seem able to assert any kind of discipline on Israel.

.

.

Once Eric does start playing for the cheap seats, he stages the destruction of the last working car in America, a spectacle of consumer outrage perpetrated by loony daredevil Roy Budnitz (Meat Loaf), and a boxing match between a mother and a son (May Boss and Jay Leno). But he balks when the chosen host of the telethon, Monty Rushmore (Harvey Korman), suggests an onscreen killing, and becomes increasingly detached from the show. Monty himself is a flailing ham who’s sunk from major film stardom to starring in that drag-queen sitcom: Vanderhoff signs off on him because he has a heart ailment and a major drug problem (he has a suitcase full of pills in every shade of the rainbow) and is likely to drop dead before the 30-day event is over. But Monty is determined to revitalise his career and power through, bitchily accosting Eric and molesting anything in a skirt on stage. Korman, so terrific for Brooks in Blazing Saddles (1974), is the arrhythmic palpitation at the heart of this film, struggling with lines that have pretences to hilarity but no actual wit, trying to invest his caricature with an edge of pathetic anti-heroism it cannot sustain. Worse, the film seems to think he has actual pathos. It’s a little like someone decided to play the Emcee of Cabaret (1972) as the empathic spirit of declining Weimar Germany rather than its septic id, or Gig Young’s Emcee from They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969) as comic foil. Similarly, the film can’t decide if Eric is a growing voice of wisdom and conscience, the wily nerd hero who saves the day with brains, or just another stooge, whilst his romantic subplot—Lucy, spurned by Chet, who falls instantly in lust with Mouling, gravitates instead to Eric—is mere window dressing.

.

.

This points to one of the biggest problems with Americathon: it sets up a semblance of traditional plot and character arcs, but fails to utilise them effectively. A major “plot” point like Chet and Mouling being kidnapped by Hebrab agents is resolved via voiceover in the concluding montage, whatever comedic or thematic value it was supposed to convey unfulfilled. Such sloppiness is not necessarily a great crime in comedy, which can thrive on narrative chaos, but in a film as hard-up for coherent focal points and genuinely inspired situations as that one, it really hurts. What few laughs the film wrings out of its later sections comes from throwaway vignettes, like the kid Chris Broder (Geno Andrews) who sets out to skateboard across America to raise funds, accompanied by his strict father (“On the fourteenth day, his father finally allowed Chris to stop for lunch”), and arrives to a heroic welcome on the Americathon stage, only to get a slapping and a shove back off by Monty when Chris announces he’s collected the grand total of $32.12. Other vignettes just seem a bit desperate, like a glimpse of the now U.S.-controlled United Kingdom where Number 10 Downing Street is now “Thatch’s Disco,” and Elvis Costello is the Earl of Manchester. Costello’s brief appearance is utterly random (although snatches of the guitar hook from his “Chelsea” constantly punctuate the film at unexpected moments), as if someone kidnapped him from the airport pretending to be a chauffeur, took him to the film set, and forced him to film a cameo for the sake of giving the film some actual cool. Costello tries to compensate for his limply patched-in status by lip-synching energetically to another of his songs before some apparently entertained tourists.

.

.

Whatever interest this film might hold today for most viewers would probably lie in its truly odd assortment of stars, many of whom are billed in TV fashion as making special appearances, like serious veteran thespian Opatashu, cunningly cast nonactor Chief Dan, a reputed Native American activist and tribal leader who had appeared in Little Big Man (1970), future faces like Leno, and stars of the moment like Costello and Meat Loaf, Cybill Shepherd as the gold-painted girl who appeals to the audience in Monty’s opening production, and the ill-fated Dorothy Stratten in a blink-or-miss role as a Playboy bunny. Riegert, on his way to becoming one of the quintessential “oh, him” faces of ’80s and ’90s movies, registers a general blank as Eric, though that’s equally the fault of what he’s given to work with. Ritter, once and future sitcom king, fares much better as the dimwit President, though his character is generally rendered too passive to be anything but a foil for others, like Buzby’s Mouling.

.

.

I’m not really sure if Buzby is great or awful playing a pop star who comes across a bit like young Marlon Brando playing a street punk stuffed into the body of a vaguely Asian woman. But she is fun, and certainly brings the biggest and most committed comedic performance by far to the film. She all but wrestles bodily with the celluloid to wring some humour from her one-note role as a lunatic who was voted “Most Likely to Take a Life” in her high school year book, insulting and humiliating the President before eagerly becoming his lover, and karate kicking the Hebrab agents who come to kidnap her. One last gag informs us that Chet and Vanderhoff settled their differences after Mouling left Chet for Warren Beatty, and both moved to Vietnam themselves where they founded a religion around the songs of Donna Summer. Now there’s a religion I could embrace.

.

.

So is Americathon as godawful as its reputation? Yes and no. The other tricky thing about humour is that it’s often so subjective. The flatly reductive definition many have of good comedy is, did it make me laugh? Well, I’ve seen other films that made me laugh less: on a laughs-to-running-time ratio, or even moreso on a laughs-to-budget ratio, I’d say, for instance, that several recent films, like Your Highness (2011) or The Lone Ranger (2013), delivered less. But comedy is subject to the same rules as other cinema genres: is it well made, well shot, well acted, vigorous in its use of form? In this regard, Americathon is a weak and shoddy work, a by-product from the end of a period when Hollywood was so desperate for galvanising talents, it took risks on hiring rank amateurs. Either way, the time for such cynicism was over: Reagan was a year away, and film critics were already doing some of his work by purposefully attacking dark and negative films—that sort of thing was so 1976.

Rod – Judging by the screencaps you sent, this one didn’t reject a single idea. The everything but the kitchen sink approach indicates a lack of judgment in choosing the best jokes and working to sharpen them, like the creators didn’t have any confidence in their ability to make a funny movie and threw everything at the wall to see what would stick. There’s something in the description of this movie that reminds me of Death Race 2000, a truly sardonic AND funny movie that made more comment on American society through the single event of the race than it would have by surveying the world situation in toto, as it seems this film does. It’s too bad the comic forces in this film were largely wasted, especially Fred Willard, of whom I am a big fan from his “Fernwood Tonight” days. Peter Riegert can be delightful in small, romantic roles, but this sounds like a mismatch.

LikeLike

Hi Mare. Death Race 2000 is a pretty apt comparison. I also thought of The Running Man a few times whilst watching it. The telethon should in theory work as a great focusing point like the race in the Corman epic, but the filmmakers don’t know how to use it for that. Yes, there was definitely a failure of both creative sifting and development apparent here; usually when we talk about studio interference we mention it in terms of negative effects but I wonder if that carelessly invested German money let the filmmakers go off half-cocked without a real fine-tuning process; it’s like the adaptation from stage to screen process was only half-finished. I too like Willard and Riegert a lot as actors but they have nothing to work with here, when the little humour that’s good is farmed out to background oddballs like Meat Loaf. Actually, that’s another problem I didn’t quite zero in on: the leads in the comedy are stuck as Zeppos.

LikeLike

Screenwriters Procter and Bergman were half of the surreal audio comedy collective The Firesign Theater, and the premise and sensibility are very much of a piece with their other work. AMERICATHON would have made a hell of an album, I think, but the sensibility really doesn’t translate to film.

LikeLike

Indeed, Jack, I had considered the peculiarity of Procter and Bergman’s problems here considering that Zachariah has a reputation, although as my blog partner Marilyn’s review of that indicated a certain level of messy enthusiasm was evident there too. Only glimmers of what might have been great on the stage are apparent here, whilst the opened-up segments tend to work better. Better direction and more careful development would’ve helped. I don’t know how good an album it would have made myself — the songs just aren’t that good (although I do also wonder how many musical numbers bit the dust in the transfer too).

LikeLike