.

.

Director: George Miller

By Roderick Heath

Mad Max (1979) was a weird and unexpectedly popular film made by George Miller, a young doctor who turned to filmmaking in his spare time during his residency training. Miller had already revealed an antic talent and gory sense of humour with his short film Violence in the Cinema, Part 1 (1971). His first feature evidently aimed to transplant the ’70s craze for car chase movies into the Aussie landscape, a smart commercial move considering that adulation of the car was and is one of the nation’s major religious movements. Miller and his initial cowriter James McCausland went a step further than the usual run of car chase flicks pitting redneck cops against raffish criminals. Perhaps borrowing a little from A Clockwork Orange (1971), Damnation Alley (1976), and Peter Weir’s The Cars that Ate Paris (1974), Miller set the film in a hazily futuristic time of a decayed social order where the roads were battlegrounds for marauders. His cops were badass neo-knights battling rampaging scum, and his hero, Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson), was that popular figure of ’70s genre cinema, the good man pushed too far by lowlifes. The film was a hit both at home and overseas, albeit after a dub job for U.S. distribution. Miller expanded the series with Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981), which pushed the concept into the realm of myth and depicted a properly post-apocalyptic landscape, and then Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985). Each film was exponentially more expensive and ambitious than the one before, and Gibson became an international star. Miller’s love of a bygone brand of big, sweeping, elemental cinema was laced with visual and thematic overtones borrowed from John Ford, Howard Hawks, David Lean, Akira Kurosawa, and especially Sergio Leone, whose offbeat, proto-punkish spaghetti westerns became a particular touchstone.

.

.

The Mad Max films have been remembered with rare fondness, particularly the middle episode, for their kinetic force, their exotic creativity, and specific, instantly influential roster of ideas and images. These films were quintessential artefacts of the early days of video, providing an easy bridging point between the drive-ins and home entertainment. Imitations exploded, at first in cheap Italian knock-offs and eventually in big-budget riffs like Waterworld (1995). In their native land, the Mad Max films were admired in themselves, and considered just about the only salvageable relics of Aussie cinema’s flirtation with genre filmmaking until the reawakened interest in Ozploitation in the 2000s; indeed, there is a serious case to be made for The Road Warrior as the best film ever made Down Under. Beyond Thunderdome, an attempt to take the series upmarket and give it Spielbergian appeal, was a great-looking and thoughtful entry that nonetheless skimped terribly on action, and many felt Miller had pulled his creation’s teeth. Ever since Miller, a truly talented filmmaker, has, like George Lucas, wasted a lot of that talent trying to be a one-man film industry.

.

.

Miller had been mooting a fourth episode since the mid-1990s, and now, finally, it has arrived with rising star Tom Hardy slotted into the lead role. Fury Road has been greeted with an enthusiasm bordering on the orgiastic by critics and fans. That’s not so surprising. The appeal of the series was always based on the outlandish and the disreputable, and the new film, armed with a blockbuster budget, has on the face of it at least the jagged, thumping appeal of a heavy-metal album in a sea of autotune pop. One unique quirk of the Mad Max series was that each episode, although linked by certain elements, represented a partial reboot rather than mere sequel to the previous one, remixing certain ideas and characterisations, thus lending itself rather neatly to recomposition 30 years down the track. Fury Road quickly reveals itself determined to a fault not to repeat the perceived mistakes of Beyond Thunderdome.

.

.

Just how deeply Australian the Mad Max films were is necessary to note outright, most particularly their sense of the landscape as both a limitlessly boding expanse and a harsh and withholding thing where paucity dictates adaptation, and their vision of civilisation as a crude assemblage of spare parts left lying about by other cultures. Miller took the Oz-gothic vision of Ted Kotcheff’s seminal Wake in Fright (1971), which contemplated the ugly, unstable tone of devolved aggression that can be seen in some pockets of the continent, and gave it a purpose. He also quoted the wild, frenetic, purposefully crude inventiveness coming out of the nation’s pop cultural quarters in the late ’70s: in the weird panoply of grotesques that form the human world of Miller’s early vision lies the grubby energy welling out of grungy pub rock scenes, art schools, and the burgeoning gay and punk scenes. At the time this was cutting edge; now it’s all rather retro. Miller went to town mimicking the sweeping widescreen visions and strident, epic-sounding music associated with a brand of big movie-making that was fallow for most of the ‘70s: Miller made blockbusters on a budget. Mad Max: Fury Road, which cost $150 million, can’t argue such handmade pizzazz, and Miller had to work his fascination with creating weird little worlds and exploring their sensibilities with a near-constant barrage of thrills and spills.

.

.

Hardy’s Max is glimpsed at the outset framed against the horizon, gazing into the distance, before stamping on a two-headed mutant lizard in an attempt to quell the semi-psychotic buzzing in his head—the voices of the people he tried and failed to save in the past, including his daughter. No time to stand around, however; Max quickly gets into his battered, old Interceptor and flees ahead of a squadron of hunter hotrods. They manage to wreck his vehicle, drag him out, and take him to the Citadel controlled by Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne), a hulking aged warlord. Many citizens of the Citadel suffer from “half-life,” or a congenital anaemia usually accompanied by cancerous tumours that cause early death, and one half of Joe’s power rests on his ability to find strong donors to keep the others alive; the other half is control of an underground water supply. The culture of the Citadel includes his army of “War Boys,” young half-lifes kept functioning by blood donors, or “blood-bags” as they’re called, and controlled through promises of an afterlife in Valhalla if they die in combat for him. Joe also has a coterie of beautiful young woman kept as a concubines in a vault. Max is tethered, and his back is tattooed with his status as a universal donor. Before his captors can brand him, Max breaks free and nearly escapes, only to be recaptured. He’s given to one waning War Boy, Nux (Nicholas Hoult), as a blood-bag. Meanwhile Joe’s top “Imperator” Furiosa (Charlize Theron) leads men out on a supply run to the nearby cities that produce fuel oil and weapons Behind the wheel of her war-rig, an armed and armoured long-range fuel truck, Furiosa drives off the beaten path into the wastelands, stringing along her soldiers and plunging them into a battle with wasteland marauders. Joe soon realises what’s happened: Furiosa is helping the concubines escape.

.

.

Characterising Immortan Joe as a primitive tyrant with a taste for harem flesh might be seen as Miller having a sly dig at one of the basic appeals of his creation: the possibility that future civilisation decline would return humankind to barbarism and the unrestrained indulgence of primal appetites and discourteous sexuality, a notion exploited all too enthusiastically by the not-so-different Gor novels by John Norman. Some of the ugliest moments in Miller’s first two films in the series involved the pansexual rape habits of its villains, so Miller may be issuing a mea culpa as he takes on the theme of liberating sex slaves. The storyline mildly upbraids such a fantasy landscape’s appeal in repeatedly noting the stripping away of dignity and agency, something inflicted on Max as well as the young concubines, as he spends many scenes strapped to the front of Nux’s car as he gives chase, feeding him lifeblood. Easy enough, too, to read Joe as a caricature of just about any arbiter of social control, as he keeps his War Boys’ heads screwed with religion and his populace on a leash with carefully rationed water: he warns his populace as he pours water upon them not to become addicted to it, lest they resent its general absence.

.

.

Nux has the strongest, most interesting character arc in the film—point of fact, the only character arc. He charges into battle with fellow berserker Rictus Erectus (Nathan Jones), mouth spray-painted with silvery gloss to evoke the chrome-plated bumper bar of Death, desperate to live up to his creed only to be jolted out of the death-hungry obsession by his own failures. He slowly changes loyalty to the ragged team of heroes whilst Erectus becomes his personal nemesis in the pursuing armada. Hoult, usually cast as cupid-lipped young romantics, has a blast playing such a loose-screw, physical character.

.

.

Meanwhile the coterie of pulchritudinous fugitives—heavily pregnant favourite The Splendid Angharad (Rosie Huntington-Whiteley), flame-locked Capable (Riley Keough), Toast the Knowing (Zoë Kravitz), The Dag (Abbey Lee), and Cheedo the Fragile (Courtney Eaton)—are characterised not as feyly naïve or absurdly tough, but as a pack of sarcastically articulate waifs out of their depth and yet committed to their Quixotic mission, tucked under Furiosa’s wing and doing their best to operate in the ferocity of the moment. I’m not quite sure if anything about their characterisations makes sense in context, though. They’re children of the post-apocalyptic world but say they don’t want their children to be warlords. What else are they going to be? Conceptual artists? Miller should have gone back to Kurosawa to remind himself of how characters set in worlds run by different rules should act.

.

.

Max’s first proper glimpse of this coterie of bounteous female forms has them arrayed against the desert sand and sky in diaphanous silks and chastity belts like some particularly collectable Sports Illustrated foldout. Furiosa herself likes to shave her head and rub engine grease on her forehead as war paint, and has a mechanical left arm. Theron proves again she’s a performer of sneaky craft as she finds depth in a swiftly sketched character with real art, moving supply and convincingly from steely war face to shows of pathos and personal longing and anguish. Her Monster (2003) Oscar notwithstanding, I can’t help but wonder if Theron hasn’t finally found her metier here as a rudely charismatic bruiser. That Furiosa is in many ways the real protagonist of the film is Fury Road’s open secret. Max is at first frantic to the point of, yes, madness—understandable considering the indignities he suffers in the film’s opening scenes. He finally breaks free when Nux crashes his vehicle chasing Furiosa’s war-rig into a sandstorm, and his initial meeting with the cabal of females is a tense and coercive standoff, as he’s initially obsessed only with survival. Standoff turns into a three-way punch-up, as Nux, still chained to his escaped blood-bag, leaps into the fray, and Max alternates between fighting off Furiosa and stopping Nux from killing her. Max at first tries to leave them all behind, but finds the war-rig won’t go because Furiosa’s kill switches have to be cleared in an order only she knows. Furiosa convinces him to take her and the other women aboard, and, of course, uneasy partnership soon becomes unshakeable alliance.

.

.

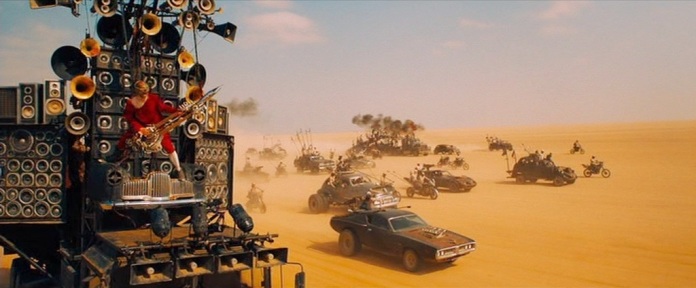

The basic story of Fury Road reminded me more than a little of Vladimir Motyl’s White Sun of the Desert (1970) with way more action, blended with a solid B-western like Charge at Feather River (1953). Miller sprinkles stirringly bizarre, funny-appalling flourishes throughout Fury Road, proving something of his old, wicked sense of humour remains. Joe has a battery farm of tubby ladies having their breast siphoned as foodstuff that Joe trades as a delicacy. The escaped concubines pause to rid themselves of their detested chastity belts, which have barbed spikes protecting them from penetration. A remote patch of bog is home to a tribe of weirdoes living on stilts. Joe’s armada comes equipped with one vehicle carrying multiple drummers and electric guitarist for mobile war music, a touch that represents Fury Road’s most inspired nod to the rock ’n roll spirit that lurked within the original series’ texture, as well as providing perhaps this entry’s keenest example of the series’ habit of melding ancient ideas with the new. If Fury Road was nothing but such moments, it might have added up to a gonzo classic of crazy-trashy inspiration. But there’s not nearly enough humour to the film, nor enough real inspiration to its running set-pieces.

.

.

Here we get into the greater problems with this entry. The price Miller has paid to make such an inflated reboot has been to do like a lot of modern action directors and essentially turn the last act—the climactic chases from the second two original Mad Max films—and inflate them into an entire movie. The first half-hour sets a hard-charging pace the film can’t sustain but damn well tries, what with Max’s attempted escape through the labyrinth of the Citadel whilst besieged by flash-cut memories of his past failures quickly segueing into Furiosa’s escape. I was near being put off the film right from get-go: Miller over-directs to an absurd degree as he sets the film racing, starting with that annoying CGI lizard and the tumult of psychic ghosts tormenting Max that reduce the necessary reintroduction of the character to a barrage of cheesy camera effects. The very opening suggests a dialogue of intense, meditative quiet and thunderous action might begin, but instead there’s only thunder.

.

.

Miller’s most inspired touches of world-building are steamrollered into the tar along with everything else. The illogic that’s often leaked out the edges of Miller’s world—the amount of petrol the villains wasted in The Road Warrior was about the same as what they were chasing—here returned in watching Immortan Joe piss water away on desert sands. Apparently none of his subject populace of human flotsam have thought to put in some kind of collecting basin or sink. Miller has his image of mock-beneficent tyrant’s egotism and human pathos, and goes no further in setting us up with either a social metaphor of real force or a villain of great stature. In spite of the film’s thematic evocations, it’s as simplistic on the level of metaphor as can be, and the raving about the film’s feminist angles in some quarters ignores the fact that the “hero saves evil king’s sex-slaves” plot is one of the oldest in pulp adventuring. Of course, we live in a time where crude and basic lip-service to political themes in movies is popular for painting our Rorschach sensibilities onto (see also The Hunger Games films), so Fury Road is quite on trend in that regard. For all the faults of Beyond Thunderdome and its big, shameless debts to Lord of the Flies and Riddley Walker, it had a depth and a wistful poetry that completely eludes Fury Road, in moments like the haunting scene where Max is treated to a creation-myth-cum-history via a relic Viewmaster where random images from a vanished civilisation have been patched together to illustrate it. There’s a hint of this in the recurring phrase asked by the concubines, “Who killed the world?”, indicting the warmongers of the future with the warmongers of the past, but without pausing to note the irony of trying to touch on pacifistic themes whilst dancing the audience giddily into a sea of carnage.

.

.

Once the action kicks into gear, the early battles and the finale are the strongest, but in the middle comes some well-staged but uninspired stuff, including an attempt to get the war-rig unstuck from the mud, whilst one of Joe’s allies, the Bullet Farmer (Richard Carter), randomly and stupidly fires off his guns into murk. It begs the question: how did any of these halfwits survive the apocalypse? Miller can think up a lot of things, but not a nonviolent action set-piece for his truckers that can hold a candle to the sequence in Ice Cold in Alex (1959) where the heroes have to hand-crank their vehicle up a hill, or the bridge crossing in Sorcerer (1977).

.

.

In spite of the film’s efforts to honour the force of the original trilogy’s realistic action sequences, here swathes of CGI still must paint the skies. Still, Miller’s respect for landscape and physical context emerges throughout. Production problems meant that Fury Road had to be shot in Namibia rather than the hallowed turf of the Aussie outback, but the vistas are just as powerfully barren and stunningly vast (if also heavily digitally tweaked), and many of the best, though relatively few, moments of the film come when Miller draws back to behold this grand arena for perpetual human foolishness. One touch that did tickle me was Miller basing some of the wasteland marauders’ vehicles on the famous spiky Volkswagen Beetle from The Cars that Ate Paris.

.

.

Dramatically speaking, Fury Road is a near-total bust however, often reducing the honourable creed of the junk action flick to moving wallpaper of bangs and booms and crashes. They’re damn well done bangs and booms and crashes, make no mistake: Fury Road is a magnificent movie production, one that clearly demanded inspiring levels of commitment to put together. But like last year’s John Wick, which also gained many plaudits from critics I’d expect to know better, Fury Road frustrated me with the presumption that an action flick can and should just be a series of Pavlovian set-pieces. Miller has a talent for fitting vignettes of humanity into the sprawl of excess, and the ones that come are interesting, like Furiosa admitting she wants “redemption” for aiding Joe for so long, and Nux connecting with Capable, the least cynical of the escapees; Keough gives a quietly luminous performance that stands out amongst her fellows, though that might be because she actually has a proper interaction with another character. But the character reflexes are astonishingly clipped and basic. Nux changes side with barely a blink, and Max and Furiosa shift from trying to kill each other to palsy-walsy in a couple of minutes.

.

.

The bad guys particularly suffer from this thinness. Part of the force of the first two Mad Max entries lay in the fact that Miller was willing to contemplate, horror-movielike, the dread of characters failing in their personal missions of protection and the loss of loved ones to the new barbarians, and his ability to think up cool avatars of evil. Here Miller reduces that element to backstory visualised in the worst way possible. Keays-Byrne’s velvet-voiced, charismatic, if often overripe, presence was one of the most entertaining in Aussie TV and film of the ’70s and ’80s, and it’s great to see him restored to his rightful place as overlord of villains. Yet he’s completely wasted as Immortan Joe, who’s just a weak retread of Lord Humungus, lacking his real physical menace, mixed with traits from Dune’s Baron Harkonnen, and he remains a mere action figure in place of a villain. Perhaps it’s admirable we don’t get scenes of the concubines being raped or mistreated, but the film lacks basic melodramatic spurs and thus the delight in seeing evil regime churned into scrap metal. Moreover, Joe’s actual comeuppance is so clumsy and helter-skelter that I almost wondered why Miller bothered.

.

.

Furiosa, finding her beloved childhood birthplace no longer exists and sinking to her knees to scream in fury to the desert, is supposed to register as an emotional highpoint, but doesn’t really cut it, considering the character’s had about 15 lines of dialogue and the hoped-for Eden has only ever registered before as a tossed-off McGuffin. Late in the film, Miller introduces a new set of protagonists to add to the band of heroes—the Vuvalini, a small remnant tribe of women ranging from young and dashing “Valkyrie” (Megan Gale) to aged matriarchs, including “Keeper of the Seeds” (the always wonderful Melissa Jaffer). Like so much else in the film, these ladies deserve and demand far more time to impress themselves upon us, and the notion of a pack of gun-wielding grannies on choppers is delightful, but they’re tossed into the drama moments before the big finish revs up. Thus, moments like the Valkyries’ eruption into battle don’t carry much weight: it’s just more stuff happening.

.

.

Frankly, although the final chase sequence represents a breathless piece of cinema construction and risky filming, I didn’t enjoy it half as much as the jungle chase of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), which emphasised fluid lines of camera motion to better read complex action using moving vehicles as mobile platforms in a running battle. Miller tries to do the same thing here, but changes camera positions and edits the stunt work too frenetically, with no sense of rhythm for the daring and the interplay of elements to register. But perhaps the biggest void in Fury Road is Max himself. Hardy seemed on paper like perfect casting as Max redux: he’s an actor of great sensitivity who has powerful star presence and also can look convincingly tough. His performances in Warrior (2011) and The Dark Knight Rises (2012) elevated both: the mordant humour as well as threat he invested in Bane has proven over time to be one of the latter film’s coups. But here he proves startlingly weak. At first he makes a stab at an Aussie brogue, but his accent skids about like slick tyres on an oily road, and he sometimes barely seems present in the movie. Trapped behind the mask he wears for much of the film, Hardy looks vaguely like some downmarket Daniel Craig clone. This isn’t entirely his fault. If I didn’t know better I’d suspect the screenplay was, like the second two Die Hard movies, one of those blockbuster imitation spec scripts that someone thought might as well be repurposed as a sequel for the model, so disposable is Max’s presence throughout much of the film. Max has been robbed of all of his mythic stature and specific gravitas.

.

.

I have suspected one of the reasons the series lay fallow for so long was because by the end of Beyond Thunderdome , Max as a character had reached a point in stasis. For all the alarum and affray here, it’s still rather obvious that Miller is unwilling to nudge him even slightly past the pose of eternal wanderer. That’s not necessarily a problem—after all, Zatoichi clocked up 20-odd films in his rootless wanderings and remained entertaining—but Max here just never feels particularly important, vital, or distinctive. The man who “carries Mr Dead in his pocket” has become just another player in a busy landscape. What Fury Road does well is just about the only thing it does: stage fast-paced road action. Fury Road is a triumph of high-powered editing masquerading as awesome swashbuckling fun, but much of the soul of this creation has been left by the roadside like so many burnt-out spark plugs: it’s an almost complete dud on an emotional level—and this kind of filmmaking runs on emotion. Yes, it is a good action movie. But it could have, and should have, aimed higher.

Roderick, great review! The movie? Absolutely overrated!

LikeLike

Hi Andre. Man, almost anything receiving the plaudits this has been getting would seem overrated.

LikeLike

Honestly, I almost hated to go and see Beyond Thunderdome, knowing Max was about as perfectly finished as I thought he should be, and the seeing the retreading for BT was already plenty in evidence. It was an interesting film to look at, but not as visceral as The Road Warrior, so it was meh for me. I’ll see this one, although too much CGI is hard on my vision, literally, always has been, which makes me wary about film in general these days. I’m afraid it’ll be a lot of coulda, woulda, shoulda…

LikeLike

Roderick, I suppose I’ll always like this one better than you will, but your remarks re: Thunderdome remind me that many who praise Fury Road feel obliged to damn the third picture while doing so, and I don’t really understand why. It may be the least of the Max films but it’s still a fine fantasy-action film with many memorable moments besides the action scenes. As for the new film’s minimalism when it comes to Max himself, I seem to recall that Miller once envisioned a film set in Max’s world, but without Max. Perhaps Max’s presence is simply a concession to the marketplace, though any assumption that the character presold the film seems overly optimistic in retrospect. It was a pretty light crowd when I saw a 3D matinee — and if I seem unreasonably bowled over by the picture 3D has a lot to do with that. Both the action and the epic production design really pop when you wear the glasses. I suppose the film is due for a little debunking, but you’ve been admirably judicious in going about it.

LikeLike

Man, oh man. Someone after my own heart. Whenever I dislike a universally-lauded film, I can at least understand what people are appreciating it for. All the raves here completely go above my head. Masterpiece of action filmmaking? Great set pieces? Endless invention? Not in the movie I saw.

What a terrific review! It took me some time to read it, but so many great points. Perhaps the first negative review of the film that actually gets why this film is mediocre. The second-to-last paragraph just about nails it. For all the claims of realistic action, it disrupts the spatial integrity in a way that hurts the spectacle.

I was just worn out watching the film. Not for a moment did I even move forward from my seat. It was all such alienating action without any air to breathe. And its pseudo-liberalism is the worst kind of audience-baiting.

Bravo!

LikeLike

Hi, Van, Samuel, JAFB:

I would underline the fact that I didn’t hate the film at all. But I went into the film determined not to be overwhelmed by raw audio-visual force, which might indeed mean resisting the film’s basic point, but so be it: no film should just be raw audio-visual force.

I don’t care that much about CGI as long as it isn’t used in crummy ill-advised ways (and I have seen plenty of that), particularly where real stunt work is required. And as far as that goes Fury Road is an improvement much of the time. But it’s hardly a CGI-free zone, and Miller turns quite a lot of his car crashes and crushes into semi-painted frames that kept reminding me of Roy Lichtenstein. And much of the stunt work isn’t that well filmed, at least not in the sense that it helps build the feeling that characters you know are doing incredibly dangerous things. Like that bit when Max went off with the Wild Boy on one of those wobbly poles. It has no effect because Miller can’t convince me Tom Hardy is really wrestling a guy on a giant car aerial. The various battles in The Raid 2 have the visceral intimacy these lacked.

I understand some of your feelings about the graduation from The Road Warrior to Beyond Thunderdome, Van, but Beyond Thunderdome has its fine points, and it at least has ambition beyond mere grunt work, and I am inclined to reward that. Whereas Fury Road badly lacks ambition or willingness to expand on its brief. Richard Brody quite rightly put it over his knee for the shallowness of its ideas and politics in a manner I felt instant sympathy with.

Nonetheless in spite of your worries Samuel it’s becoming quite a big hit – pushing over the $100 million mark at the US box office and much more than that internationally (of course, we Aussies are stoked); it’s an achievement for a 30-year-old franchise restart without a family audience to tap. But yeah, I can’t help but feel Miller should have put far more effort and emphasis into re-establishing Max for an audience of newbies, both in advertising and in the film. I can easily imagine some teen who’s never seen any of the earlier films watching this and wondering why the hell that guy’s got his name on the title. The reason why Beyond Thunderdome must be damned, however, is that as in so much current pop culture, there is at any given moment a right way and a wrong way to handle a popular property, and Beyond Thunderdome is the wrong way, dying to give rebirth to Fury Road, which does all things for all men. Which in this case is, turning the brain off.

It seems, Film Buff, we had close experiences and reactions. I can see to a certain extent why this excited folks. From moment to moment it’s a triumph of staging, and yet I felt the overall guiding hand you see in truly great action set-pieces to be lacking: Miller exchanges invention and structure for endless repeats of the same essential moment. Technical swagger is something a lot of movies have today, and as I said about John Wick, although I liked this more, if this is the action film of the future I think I’ll take the past. And the less said about the attempts to paint the film’s vaguely political themes as revolutionary the better. Frankly I think it’s just dancing to a tune written by Miller for careful marketing value.

LikeLike

I don’t fundamentally disagree with most of what you’re saying, but I think you’re missing the humor or even joy in the ridiculousness of many of the details — the drum car, the flame guitarist, the warboys bobbing around on poles and dropping out of the sky. I laughed aloud at a number of these moments. My enjoyment went beyond the usual action-enjoyment because of the unapologetic metalness (for lack of a better term) of it all.

LikeLike

Rod, some of us have worried that Fury Road would seem a flop compared with Pitch Perfect 2, and my defensiveness toward the film probably was established before I even saw it when I saw Mick Lasalle (the syndicated newspaper reviewer) give it two stars to PP2’s three, and in a way that suggested, given Lasalle’s current antipathy toward action movies, that this was a moral judgment. Your own comments about “right” and “wrong” are apropos given a feeling that the “wrong” film won the box office race that weekend, or a worry that the results proved FR the “wrong” film for the moment. Crazy, right? But to continue the theme, I suspect that many reviewers have praised FR in a way you find excessive in order to have a stick to beat Avengers and its ilk with, Miller having shown them the “right” way to do an action film even as the Marvel manner grows tiresome to many. Your suggestion that the differences that seem to elevate Fury Road are only superficial compels some reconsideration, but I can’t renounce my near-complete satisfaction with the picture, though that may only mean that what you saw it lacking I didn’t need.

LikeLike

Mike; I certainly enjoyed those touches too, and that was one of my problems — I could’ve used a lot more of them. The special kick of the sight of the drummers and guitarist was admittedly spoiled by reviews and online conversation. If it had come out of the blue I might have been disarmed by such a flourish more properly.

Samuel; ‘I suspect that many reviewers have praised FR in a way you find excessive in order to have a stick to beat Avengers and its ilk with, Miller having shown them the “right” way to do an action film even as the Marvel manner grows tiresome to many.’ That’s dead on the money as far as I can tell. And I understand to a certain extent whilst also raising a cynical eyebrow (give ‘em a whole bunch more films like this and they’ll be pining for the classical method of Marvel). And if you felt satisfied with the movie as is, that’s nothing for me to worry about, but I still wanted more thought put into it. Anyway, as it’s working out, Fury Road and Pitch Perfect 2 have been proving that two films can rack up blockbuster earnings at the same time by appealing to two near-completely different audiences.

LikeLike

Everything about this one seems overcooked. In contrast, Thunderdome was maybe sort of underdone, but was actually a reasonable rehash of Road Warrior if slightly unnecessary. While I haven’t yet seen Fury Road, I must stand up for one particular Miller film post Thunderdome- Babe:Pig in the City, which I think is a masterpiece of its genre.

LikeLike

Hi PP, long time no see. I revisited Beyond Thunderdome a couple of weeks before seeing Fury Road because it was the Max movie I hadn’t seen in the longest and because I wanted to compare the film I remembered with the invective being thrown at it. It definitely has faults — too much kiddie adventuring and a curtailed, rather weak chase finish. But frankly I think if put to the torture I’d have to admit I still preferred it to this. It has thoughtfulness and some truly inspired imagery, whereas this has…pizazz. I must admit to not having seen Pig in the City, although many feel towards it as you do, I know.

LikeLike