.

.

Director: Michael Mann

By Roderick Heath

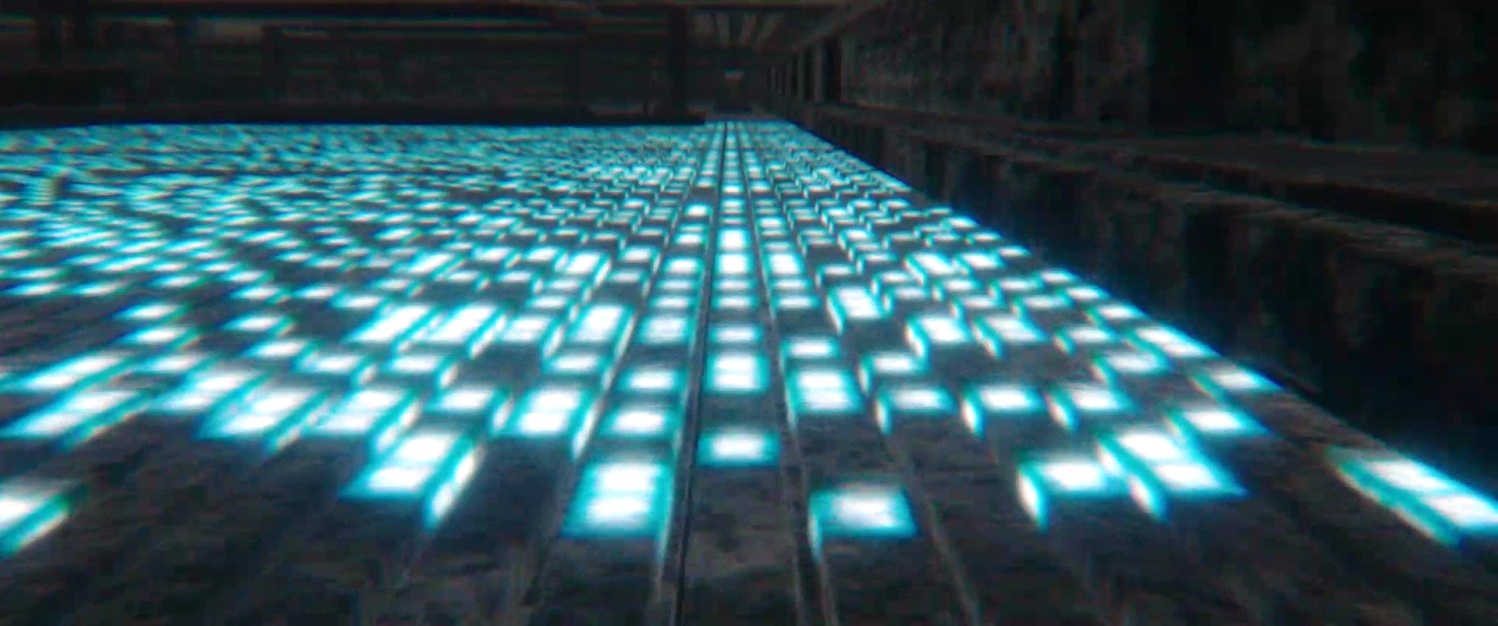

New frontiers, vast and infinitesimal: Michael Mann commences Blackhat with a brief symphony of cinema comprising visions of systems micro and macro. The Earth is pictured from space, not as a zone of seas and continents, but rather as a glowing mass of connections, a wired-up world, before plunging into the tiniest components of a computing system, where the flow of electricity and energy sets in motion grand dramas. Microscopic grids flow with pulses of energy, tripping the gates of information flow that define the digital mechanism. Mann then pulls back to observe the interior of a nuclear power station, just as alien and geometric as the innards of a silicon chip, circuit boards and nuclear cooling rods as indistinguishable, symmetrical hunks of hardware. The streets of supercities unfold in the same geometric forms in a colonisation of the mind and the world by the precepts of the abstract and the mechanistic. Blackhat is at once a stripped-down, businesslike machine of a film, and one that bears the weight of summarising Mann’s career with covert elasticity. Blackhat is Mann going internationalist, finding the computer age is just as wide open and lawless, replete with shadow-enemies and doppelgangers, as Mann’s wilderness society in The Last of the Mohicans (1992) and the mean streets of his neo-noir films, backdrops of burning sulphurous light and ashen, digital dark. Borders are disrespected to the point of invisibility in the new digital world, and the systems of the human world aren’t just failing to keep up, but lie immobilised, distraught at the collapse of familiar fiefdoms and settled dominions.

.

.

A “blackhat,” slang for malicious internet corsair, hacks into the mainframe controlling a nuclear power station in China, shutting down the water pumps for the reactor coolant, causing an explosion and threatening a meltdown. Shortly thereafter, the same insidious computer program is used to hack into the New York Stock Exchange and start a run on soy futures. The Chinese government reaches out to the U.S. through young, American-schooled, cybercrime expert Captain Dawai Chen (Leehom Wang) to instigate a joint task force to track down the all-but-ethereal criminals able to reach into the heart of nations. Dawai asks his sister, Lein (Tang Wei, the moon-faced tragedienne of Lust, Caution, 2006), to turn her computing expertise to the problem and come with him.

.

.

The Americans cautiously agree to help, with the task force’s team leader, FBI Agent Carol Barrett (Viola Davis), under orders to move carefully and not risk any security exposures to the Chinese. Probing the fragments of the “RAT” (remote access tool) coding used in the hacks, Dawai is shocked to recognise it as something he wrote in college his roommate and pal Nick Hathaway (Chris Hemsworth) as a show-off gag. Nick has since been imprisoned for a long stretch after using his prodigious hacking gifts to siphon millions from various financial institutions, but Dawai argues successfully that only the man most responsible for creating the code might be able to help unravel it. Nick is released, albeit with a tracker on his leg and U.S. Marshall Jessup (Holt McCallany) as watchdog until he comes up trumps or heads back to jail.

.

.

Nick soon proves his worth as he deduces how the stock exchange was hacked—it was by a criminal who got himself a job as a janitor inserting a USB stick with the malware into a mainframe computer. The team quickly tracks down the criminal and find him dead from an overdose, but his computer still offers a thin thread that leads them on through a web where the spider sits in a nest tugging on strings setting hardware—human agents—to facilitate and protect the real action, which takes place deep in the infinite sprawl of fibre optics and circuits. Hacking and cybercrime are pervasive facts of the modern world, but they have proven notoriously tricky, unpopular subjects for filmmakers (and given Blackhat’s box office, probably likely to remain so). Mann negotiates his way into this world with a key assumption that the world of virtual crime and real world crime are not really that separate or distinct.

.

.

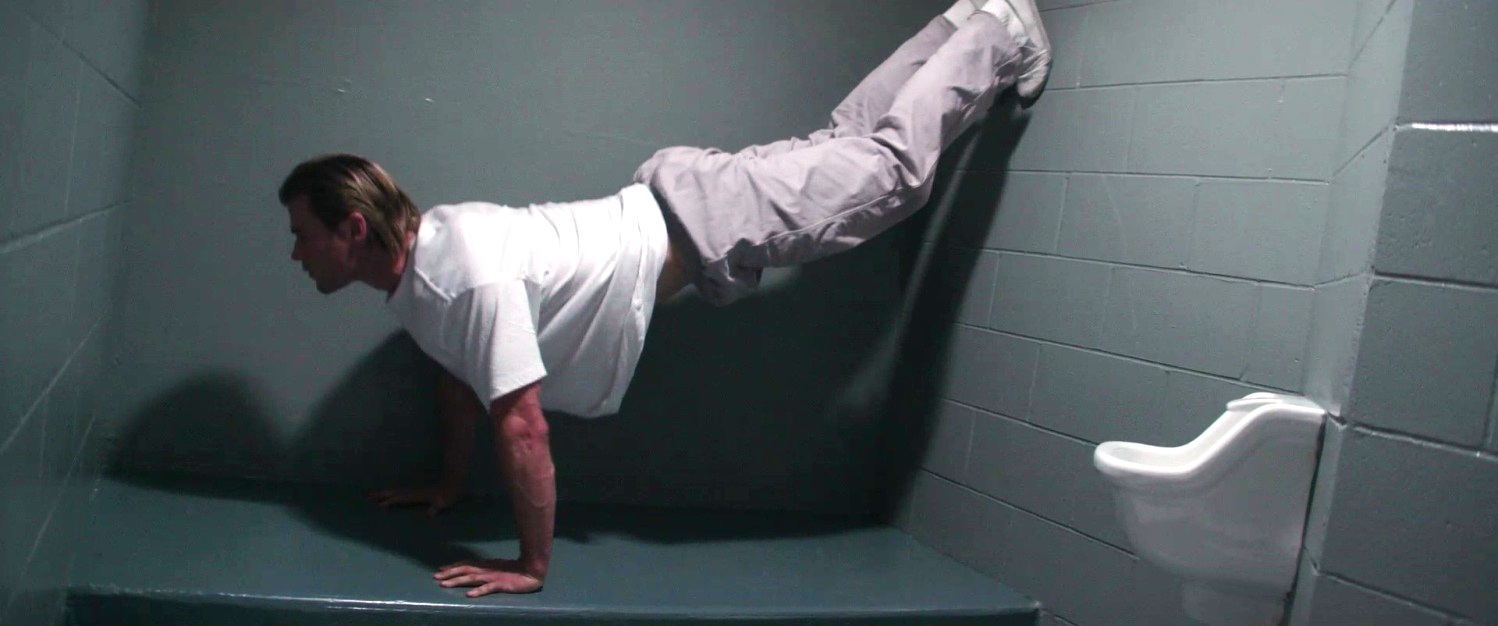

Mann’s career has been built around probing and dismantling pop culture archetypes—cop, criminal, monster, hero, and perhaps most particular to American mythology, the lone man in the wilderness, be it primal or urban, doing battle alone and becoming one with his tools to survive. This is the kind of person colonial nations tend to mythologise, and yet work assiduously to snuff out in real life. They can be heroes in Mann’s work, but more often are rendered antiheroes because they can’t be assimilated. Nick is the latest in the long line of such figures, whose profoundest epitome is Hawkeye in Mohicans. Nick, once a soft, larkish college genius, has been hardened by two stretches in prison, the first a brief, but tough spell in “gladiator academy” as punishment for a bar fight gone bad. His hopes for a great tech career foiled, he felt forced to turn his talents to nefarious ends, taking out his inferred rage at the world on banks and other institutions he considers corrupt, leading to his second, lengthy sentence. In our first glimpse of him, Nick is attempting to maintain a bubble of self-created reality, reading Foucault and listening to music on a headset. Guards burst in and start tossing his cell, treating Nick to a face full of mace and carrying him out head first when he protests about someone standing on his book. The warden accuses him of using his iPod to hack bank accounts and give all of his fellow prisoners $900, but Nick retorts that he only used it to call up Santa Claus.

.

.

Mann refers right back to his debut with Thief (1981) and the epic diner gabfest of James Caan and Tuesday Weld, through to Heat’s (1995) famous coffee-break meeting of Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, when Nick and Lien settle down for a toey one-on-one in a Korean restaurant, an Edward Hopper-esque zone of social neutrality and tenuous connections afloat in the night. Nick explains in assured, yet uneasy fashion his wilful dominance over his situation through exercise of the mind and body. Lien retorts that he still sounds like a man mouthing mantras to himself in jail, staving off the moment when he has to actually face the reality of living the rest of his life. Somehow, Mann manages to shoot Hemsworth in such a way that he seems composed of the same igneous material as some of his predecessors, from Scott Glenn in The Keep (1984) to Will Smith in Ali (2001), his usually bright surfer boy face recast as dour, sulky, grey with a prison tan even as he’s built himself into a hard machine of muscle as well as digital prowess (pace all the stupid hacker stereotypes Hemsworth doesn’t live up to).

.

.

Mann’s gift for pirouettes of imaging that dispenses with a need for underlining dialogue has already yielded a breathtaking vignette of Nick, released from prison and escorted to the airport, pausing for a moment in wonder and fear in contemplating open space, Lien’s fingers folding about his shoulder a momentary shock of empathic human contact more alien than the bruising, bloodying tussles behind and ahead of him. After Nick’s first grilling by the prison warden, he’s put in solitary, shut away from his music and books: most directors would have made this the moment when Nick’s stoic façade drops, but Mann instead shows Nick pull completely within himself and start doing power pushups, readying himself for a day of battle still to come.

.

.

Mann creates in Nick a character who is at once supremely modern, aware and gifted at penetrating the veils of contemporaneity, but also schooled in ancient arts, a man stripped back to the essentials of his nature. A similar schism fuels Blackhat, the very title of which suggests classic genre motifs, the black hat of the Western villain, turned digital avatar, and very old games played with the shiniest toys, but finally regressing from super-modern to street fight. Blackhat, underneath its thriller surface, is perhaps closer kin to scifi, one of those epic tales of a civilisation that devolves from atomic power to sharp chisels and knives in the course of a conflict, as if Mann is playing 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) in reverse, or transposing “Genesis of the Daleks” (TV, 1975) onto the contemporary geopolitical frame. Indeed, so much of today’s geopolitical purview is a battle of disparities—holy warriors taking on drones, improvised explosives breaking armies’ hearts. In Public Enemies (2009), Mann noted the prototypical surveillance culture of modern law enforcement counterbalanced by the raw firepower suddenly available to criminals. Mann saw that age as rough draft for later decades of state power versus armed radicalism, rival organisms with internal factions both idealistic and evil, an idea he brings to the threshold of futurism here.

.

.

In the same way, Blackhat contemplates computer technology as both enforcer of hegemonies and device for assaulting them, and the moral imperatives that vibrate throughout the film question the viability of rapidly dating systemics (countries, law enforcement agencies) versus swiftly evolving ones (terrorist organisations, online crime), and the characters’ fluctuating status between the ramparts. Although violent action combusts several times in the course of the film, the crisis at the core of Blackhat’s narrative isn’t a shoot-out or a terrorist attack, but a squabble between different branches of law enforcement. Carol tries to get help from an NSA contact to use Black Widow, a hush-hush piece of software that can resurrect deleted data, but her request is turned down because of the faint possibility of the software being leaked to the Chinese—so whilst that same program was used to nail Nick for crimes against capital, looming assaults against populaces must be ignored. The elephantine nature of the modern state is an illusion of control; the white ants invade the substructures. Although Nick’s entry into the team of law enforcers initially sparks conflict between Dawai and Carol and place Nick in an adversarial position, his gifts in the dark arts of hacking, an incoherent sprawl of hieroglyphs for most eyes, prove a powerful weapon, as does his hard-won street smarts. The two don’t always mesh so well, as when Nick tries to scare his invisible enemy with prison yard threats, only to relearn they don’t work over the wires. But when real thugs fall upon him and Lien under the scrutiny of remote eyes, brawler tactics work wonders as Nick is reduced to slashing enemies with broken bottles and slamming tables over their heads.

.

.

The uneasy alliance of individuals and motives forced together in the pan-Pacific task force melds eventually into a unit of diverse yet harmonious talents. This is a familiar genre motif with specific echoes of Howard Hawks’ fascination with such teams, albeit one Mann sets up only to demolish with exact and startling force later on. Mann lets them have moments of glory in the meantime, as when Carol expertly bullies a resisting Wall Street honcho (Spencer Garrett) into handing over records from the soy run to get a lead on the siphoned money—a particular highpoint for Davis, in the way her character’s mix of wary intelligence and deeply sad weariness seems tattooed on her face, amidst a great sustained characterisation. The breadcrumb trail forces the team to relocate to Hong Kong and confront a gang of heavies run by Kassar (Ritchie Coster), a former soldier turned muscle for hire, and tease out the elaborate means by which the blackhat keeps his operatives at arm’s length. The chase demands venturing into the ruptured heart of the modern world, the nuclear power station balanced precariously on the edge of meltdown, to extract vital information that can lead to the blackhat. Effective communication, as ever in Mann’s films, is a laborious task, to the point where Dawai and Nick can only effectively converse about Nick’s burgeoning romance with Lien over headsets in a helicopter.

.

.

Dawai locates the money the blackhat made on their engineered futures run, and Nick zeroes in on a remote unit that allows the agents to contact their controller without entering any wider system, but brings ever closer the point where the virtual hunt collides with the very real firepower of Kassar and his men: finally, when the money begins to move, so, too, do the guns, and as the Americans join local cops in swooping upon the suspects, a thunderous shoot-out erupts as Kassar’s insurgency approach sees IEDs and machine guns meeting the lawmen. The way Mann shoots his Hong Kong sequences suggests he might have been watching some of Johnny To’s concrete wilderness dramas, just as To surely has watched Mann’s code-of-conduct melodramas, and Blackhat vibrates with a similar sense of exposure in the wilderness of the new that is the modern Chinese landscape. Mann sees something of the same milieu as the 1930s America he analysed in Public Enemies in contemporary China, a land of haphazard novelty and striving individuals.

.

.

Mann was long regarded as a savant of style whose early work on the Miami Vice TV series helped define a haute couture-like ideal of pop culture, in tweaking the noir landscape for a different age with a different palate. Yet Mann has often pushed his sensibility further than his audience has been willing to go, from the dreamlike elliptics of The Keep to the unique, tersely beautiful blend of digi-realist immediacy and sprawling pop-art vistas in his recent films, as if someone commissioned the team that shoots Cops to remake Touch of Evil (1958). Mann’s visual language in Blackhat has evolved into a toey, restless aesthetic alternating twitchy handheld camerawork and compositions that blend immediacy with elements of expressionism and abstraction. Mann is still somewhat unique in contemporary genre cinema in that he labours to convey his films’ thematic and emotional information visually. Here, his teeming, tidal, oblique camerawork captures everyone and everything in the zone between animation and objectification, rarely conceding to this world even the dreamy lustre he gave his film version of Miami Vice (2006), perhaps because the air of unseen oppression generated by a war with an invisible enemy and Nick’s sense of exposure in the world define this tale and its telling, rather than the druglike, ephemeral romanticism of the earlier film.

.

.

The fascination with humans subordinated to controlling structures evinced in Public Enemies likewise arises. The first Hong Kong shoot-out sees the curves of sewer systems, arrays of concrete blocks and cargo crates becoming geometric obstacles of a human pinball machine, echoing the similarly alien sense of the world glimpsed in the work of Fritz Lang and Orson Welles. So many of Mann’s recurring themes and obsessions recur throughout Blackhat that it becomes a virtual textbook of his cinema, a language that, like the hacker computer code, flows through the film, giving it a contiguity elusive to many eyes. Nick’s gift for blackhat programming turned to a righteous end reintroduces a theme Mann tackled in Manhunter (1986), albeit with a very different tone, with outlaw aiding lawman in bringing another criminal to justice. Nick’s brotherly loyalty to Dawai stretching across ethnic and national lines nods to Hawkeye and Uncas in Mohicans. Nick and Lien’s quickly combusting, almost ethereally intense affair recalls many throughout Mann’s works. Perhaps most revealingly, here that coupling eventually fuses into a union of mutual aid and moral as well as emotional symmetry, a blessed state that notably eluded most of their predecessors.

.

.

Blackhat is the closest thing I’ve seen yet to a contemporary Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler (1922), though Mann works from almost the opposite precept to Lang’s founding text of the paranoid thriller. Whereas Lang, working from Norbert Jacques’ novel, placed his infinitely malleable villain at the centre of the narrative and forced the audience to take the ride with him, Mann renders the blackhat himself a near-total void, a momentary personification of a force that has long since become free-floating, as indeed Lang rendered Mabuse’s legacy in his later films: anyone might do what the blackhat does if they have the tech and the will. Unsurprisingly for a filmmaker often obsessed with the noble impulses in criminals, Mann depicts Nick as a hero operating according to a private code rather than an imposed morality, and then reveals how everyone else operates the same way. Dawai uses his power to get a pal freed, and Carol and Jessup eventually make a conscious decision to work according to their private compasses, with Carol driven by immediate personal loss: her husband died in the 9/11 attack, and the spectre of further terrorist assaults drives her to agree to Nick’s most radical proposal—to hack into her NSA contact’s computer and use Black Widow to salvage the damaged information taken from the power station’s computers. This foray works and allows the team to track the blackhat’s operation to Jakarta, but the breach is quickly uncovered. Dawai is instantly ordered by his superiors to cut Nick loose, and Carol is told to bring him home in a storm of paranoia that Nick might sell Black Widow to the Chinese. Dawai, however, warns Nick, and he skips out just before Carol and Jessup can lower the boom.

.

.

Mann detonates his own film ostentatiously here, shattering his fusing team as each member is faced with a crisis of loyalty and purpose that drags them confusedly in different directions within and without. Mann then goes one further as a sudden attack by Kassar destroys the team more thoroughly: his bandit team, trailing Dawai, blow him up in his car with a rocket launcher, leaving Nick and Lien, who were just making their farewells as he was faced with a life on the run, stranded and cowering under a hail of bullets. Carol and Jessup, searching for Nick, race in to the rescue only to both be gunned down. Jessup manages to take several enemies with him in a display of professional bravura, but he still inevitably falls, caught in the open and outgunned. This sequence is stunning both in its abrupt, jarring narrative pivoting, and also as filmmaking. Mann’s signature slow-motion turns the explosion of Dawai’s car and the dance of death Jessup and his targets perform at a distance into arias of motion, before zeroing in on Carol’s face as she dies, gazing up at a tall Hong Kong building, a mocking echo of her motivation to save other people from her own personal hell before the big sleep, a fleeting flourish of woozy poetry as strong as anything Mann’s ever done. Mann has been stepping around the outskirts of tackling terrorism as an outright topic for a while now. Blackhat often feels like Mann’s companion piece-cum-riposte to the initially dark and probing, but ultimately victorious vision of Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty (2012) and its careful elisions of questions about the situations is depicted. Mann depicts the biggest obstacle to gaining justice in a post-9/11 world as the proliferation of self-interested bureaucracies supposedly erected to deal with the problem, but perhaps instead arranged to create greater insulation from responsibility, and cordoned, mistrustful states whose turning radius is so great they can’t possibly react in time to such dangers, the human agents of those states, no matter the nobility of their purview, as lost, endangered naïfs compared to the hardened natural citizens of a more warlike age.

.

.

Nick and Lien manage to flee and are forced, for the sake of both allegiance and revenge, to continue pursuing the blackhat as renegades. Nick realises that the blackhat’s real purpose, for which his initial attacks were only a test and a financing operation, respectively, is to flood a dammed valley in Malaysia, destroying a number of tin mines and sending the price of the metal skyrocketing—reversing his earlier programme to wreak havoc in the real world to affect another virtual realm, the stock market. Stripped of alliances and cover, Nick and Lien must improvise from moment to moment in their hunt, and the outlay of ruses and tactics lets Mann strip the film down to the raw elements of method: the abstract systemology of the virtual world gives way to physical operations that nonetheless run on similar precepts of disguise, retooling, and manipulation; they use low-tech devices, from knocking a van off a roof and taping magazines to Nick’s chest as improvised body armour to utilising some coffee carefully spilt on some papers as a gateway to hacking into a major financial institution.

.

.

When Sadak (Yorick van Wageningen), the blackhat himself, is finally revealed, he’s a terse, aggressive, stocky operative who might himself be only a front for other forces. He could easily be Nick himself if he hadn’t been caught, turned middle-aged, cynical, and utterly unscrupulous. Nick penetrates his icily dismissive shell by stealing all his money, forcing him and the remnants of his crew to face Nick’s wrath. The finale, staged in the midst of Nyepi Day celebrations, doubles as action climax and visual-thematic joke: the flow of humans engaged in solemn rituals mimics the grid of the computer innards, whilst Nick and his enemies bob and weave in free patterns within the system, climaxing the duel of wits, technologies, and instincts in a way that sees Nick victorious. The age of supertechnology winnows down to a cruel and intimate confrontation with bits of filed-down steel puncturing soft, warm, human flesh. This confrontation doesn’t quite reach the same level of operatic drama that Mann gained with the Iron Butterfly-scored shoot-out of Manhunter or Mohicans, but it does set a memorably nasty, intimate seal on a film that may one day find the acclaim it deserves.

“Yet Mann has often pushed his sensibility further than his audience has been willing to go, from the dreamlike elliptics of The Keep to the unique, tersely beautiful blend of digi-realist immediacy and sprawling pop-art vistas in his recent films, as if someone commissioned the team that shoots “Cops” to remake Touch of Evil (1958).”

This is the kind of observation that I wish I had thought of myself… well done! I feel that this film has been unfairly maligned and perhaps it was the subject matter that doomed it to commercial failure but I felt that Mann made one of the most realistic depictions of computer hacking since… geez, WARGAMES? I think that the screenplay, at times, is a little on the weak side, and maybe Chris Hemsworth, as much as I like him in the THOR movies, wasn’t the right guy to play the film’s protagonist. He looks the part but seems a little lost when trying to convey the soulfulness of his character. But that is my initial gut reaction after only watching it once and I really am looking forward to watching this again as I find Mann’s films tend to get better and deepen upon subsequent viewings.

LikeLike

Absolutely splendid analysis of a underappreciated Michael Mann, Roderick. Spot-on.

LikeLike

One thing I like about Mann, JD, is I get the feeling he always guts his screenplays anyway; he clearly prefers to use a gesture where most would put dialogue, as he’s always wrestling with how to convey his dramatic essence visually. And I liked Hemsworth quite a bit (I usually do) whilst wishing there was a bit more time to dig into his character. But the actor is clearly, much like Hitchcock’s stars, something of a clay model for the director: I was particularly struck at how somehow Mann got him to look so much like Scott Glenn in The Keep and some other protagonists — stern, purposefully empty of emotion and drawn into himself.

I wonder how much of the film finished up on the cutting room floor. Either way, it’s one of the best films of the year so far, warts and all.

leopard — thanks. As I noticed at the time of release, only a small percentage of critics seemed to like this, but that percentage included most of the good critics.

LikeLike

Roderick, wonderful analysis! An amazing film experience (a Wong Kar-Wai thriller). I really liked this one. My number 2 film of 2015 so far. Congratulations.

LikeLike

“A Wong Kar-Wai thriller”

That’s a description of great value, Andre; in fact I did whilst watching the film wonder at several points if Mann was drawing on Wong, and Johnnie To as well. All three men have an overriding fixation with characters lost within their own nominal societies.

LikeLike

Great Roderick. The colors, the atmosphere, the editing… Happy together, The grandmaster, 2046. And Johnnie To! I think your point is exactly right.

LikeLike

I’ve read some reviews that slammed the characterizations in the film, but I’m amazed at how involved I was with these characters, caring about what happened to them – even the anonymous cops who got blown up in the first big action sequence. I think the film finds the spiritual core of what doing the right thing really means, and so we have a lot invested in seeing the bad guys taken down. The use of the nuclear reactor and, later, the flooding of an inhabited valley, are such potent reminders of what the forces of commerce and first-world need have done to the planet. I, too, thought Hemsworth was terrific, feeling but also very practical about the need to survive.

I read that Mann used five different camera types to film this, and so even in execution, Blackhat made a comment on technology and the value of experimenting many different approaches for the evolving filmmaker and his or her audience. Even so, I was very struck with the compositions and the integrity of vision from camera to camera. It is a visually stunning film.

I did wonder, though, at his use of slowmo to signal to the audience that violence was about to ensue. Any ideas about why he wanted to prepare us?

LikeLike

Yes, Mare, I guess in this case criticism of the characterisation means lack of cheap signifiers like pictures of a lake house someone wants to retire to or a dog or something.. The people in this are what they are doing at the time, no matter what has made them so, but what has made them so also propels them in subtle ways. Daiwai is the man who’ll use his clout to get a friend out of jail. Carol is a woman who’ll do what it takes to nail a perp. All these complex creatures butting into one-another, glimpsed in this moment of high drama. Mann constantly clues us in to what it means to Nick to be free and then makes us confront the moment when he takes everything into his own hands to catch the villains and possibly destroy himself. I think Mann’s trying to get at something deep there, a sense of anger at how people who risk themselves for everyone’s good, be they soldiers or whistleblowers, usually get chewed up and spat out.

You’re right, the camerawork is tremendous and remarkable (and I’m glad you were able to stick it out this time after Public Enemies). I wish I’d been able to watch this on a big screen, but it was sent straight to DVD here. A bloody shame. I’d say, most superficially, that Mann’s penchant for slow-mo is his most obvious debt to Peckinpah. But he does use is with a subtle difference from Peckinpah; both directors are obviously both repelled and fascinated by the impact of violence and compelled by the “moment of ultimate truth” aspect of it. But where Peckinpah was fixated with the impact of violence in and of itself in all terrible beauty, Mann tracks motion like he’s out to study the plays of death-duels, trying to capture the most fleeting differentations between his heroes and villains, the very finest movements that can separate life from death; fighting tends to be something of an art in his work. There’s certainly a lot to be said about this.

LikeLike

I finally watched it tonight, I thought one of his best, do not understand the critical drubbing it took. Like that it is mostly a quiet movie, they do not signal events with a big musical flourish. He also handled the relationship between Hathaway and Lien quite well, if he has a weakness it’s probably been that sort of thing, but here he got it right. And you are right, that scene at the airport where he looks out on all that space, very nice touch.

(I remembered your write up as probably the most positive I had seen, so wanted to read it after seeing the movie. Glad someone got it)

LikeLike

Patrick, thanks for the good word. I don’t really agree with you that Mann’s romances are weak; some of my favourites in modern cinema are in his films (Stowe and Day-Lewis in Mohicans, Li and Farrell in Miami Vice). One thing I like about Mann’s love stories is his constant attempt to show how much human attraction is often a wordless, near-subliminal thing. Sometimes that evanescent quality does get lost in the sturm-und-drang, admittedly (I’m always a bit amused by how quickly Scott Gleen and Alberta Watson get it on in The Keep).

LikeLike

Very good article for a solid underrated Mann’s movie, as usual i liked Mann’s use of widsecreen cinematography, locations and soundtrack, and of course the set-pieces (the opening CGI scene, the airport/tarmac bit, the restaurant scene, taxi ride, the two shootouts, the plane taking off Hong Kong at night and the whole ending)

“Somehow, Mann manages to shoot Hemsworth in such a way that he seems composed of the same igneous material as some of his predecessors, from Scott Glenn in The Keep (1984)”

“the dreamlike elliptics of The Keep”

When watching “Blackhat” I thought of “The Keep” twice:

during the restaurant scene, there’s a close up of a stoic Hathaway’s profile/face looking a bit like Scott Glenn’s Glaeken, also the elliptical dreamlike love scene is close to “the Keep”‘s love scene between Glenn and Alberta Watson…in both films: same kind of elliptical ethereal editing and “dreamy” change of locations in one shot.

LikeLike

“a close up of a stoic Hathaway’s profile/face looking a bit like Scott Glenn’s Glaeken”

Yes, the similarity in several shots is really eerie.

LikeLike