.

.

Director/Coscreenwriter: D.W. Griffith

By Roderick Heath

One hundred years have passed since the release of the film long beheld as the very moment cinema came of age, and few films can speak so eloquently as to just how long that century has been. The faiths, ideals, and biases inscribed in the form of The Birth of a Nation, both separate from that form and wound into it with pernicious intricacy, tell us things we don’t necessarily want to remember or countenance, things that appall and beggar as well as things that still stir and fascinate. David Wark Griffith’s achievement with The Birth of a Nation was immediately hailed as a great event in the history of a young art form, but also the spur to furious debate, even murder and terrorism. The frightening power, redolent of some alchemist’s dream of mesmeric influence over a mass populace, of that new art form was confirmed at the same time as its enormous expressive promise. The Birth of a Nation became perhaps the pivotal work of moviemaking’s first quarter-century, overshadowing even Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), which it influenced, because it was a colossal hit as well as a successful aesthetic experiment. Griffith’s film would remain the highest-grossing film of all time until at least Gone with the Wind (1939), and perhaps still reigns supreme adjusting for inflation: as costar Lillian Gish put it, it made so much money they lost count. At the time The Birth of a Nation struck many viewers as like a historical document given the vitality and narrative power of legend. Woodrow Wilson reportedly described it as “history written in lightning,” though those words were probably placed in his mouth by his former schoolmate, Thomas Dixon, Jr, who proselytised tirelessly on the behalf of the work taken from his novel. The film premiered 50 years after the end of the Civil War, but everyone in the average American movie theatre of the time knew very well that the forces that had caused and ended that hideous conflagration were not yet quelled. Hell, they’re not past even now.

.

.

For a long time, no one argued with Griffith’s achievement. Certainly the most hyperbolic descriptions of The Birth of a Nation’s originality were incorrect. The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) pushed into the realm of the modern definition of narrative feature film when Griffith was still an actor. A wave of contemporaneous Italian historical films, including Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo Vadis? (1913) and Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), drove Griffith to compete with their scale and dramatic heft. Most of the editing and filming techniques packed into his work already existed, awaiting the kind of show-off who could synthesise them, and Griffith had laid claim to inventing many in his acts of self-promotion. The famous ride of the Ku Klux Klan at the end of The Birth of a Nation with its cross-cutting structure was actually just a reprise of his earlier work, The Battle of Elderbush Gulch (1913). But the record still tells us that Griffith constructed something his audience felt it had not seen before and immediately responded to as something new and amazing. He had helped define the cinema at last as its own continent, for all Griffith’s debts to Victorian-era literature and his conversion of some well-established author’s tricks into visual style.

.

.

The Birth of a Nation perturbs now for less abstract reasons: it’s appallingly racist, and not just for modern eyes. In its own time, the film was the subject of bilious protest. Many saw it then as a legitimate account of the era it portrayed; others recognised it as blatant, partisan propaganda and racial libel passing itself off as a common folk-memory. Perhaps the controversy helped its success. The fledgling NAACP gained stature and clout objecting to it. Some blame it for sparking the new Ku Klux Klan campaigns of the 1920s. Violence certainly broke out in some screening locations. Today, the success of Ken Burns’ television documentary series The Civil War (1987) and Edward Zwick’s film Glory (1989) helped restore the Civil War to the centre of modern American mythology in a way that pop culture had rarely seemed comfortable with before, partly by confronting aspects of the war that had long been repressed. For a very long time, the tacit narrative of the postwar period was one of reconciliation between former antagonists, burying the causes for schism whilst inferring that the citizens whose fates were crucial to the war, African-American slaves, were best excised from the conversation, if not in some way to blame for it all. The Birth of a Nation, to put it mildly, records and exemplifies that convention.

.

.

Griffith’s film was based on Dixon’s novel, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan. Dixon was a South Carolina minister, politician, and pro-South ideologue who had been convinced by the anecdotes he heard as a kid that the Klan had saved the South from rapacious carpetbaggers and lawless freedmen. The Birth of a Nation was initially to be a straightforward adaptation of the novel, and first screened under its title. The contradictions here are many: Kentucky-born with Confederate roots, Griffith had just a few years earlier made a film where the Klan were villains. During production, Griffith’s adaptation of Dixon inflated into something far larger than intended, as Griffith worked without a scenario or screenplay, but simply kept the book in mind whilst conjuring his visions, creating a grandiose pageant begging for a more sweeping appellation. Griffith by this time already had a reputation as one of cinema’s most innovative and distinctive talents: as cornball as a lot of his plots were, in works like The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912), The Avenging Conscience, and Judith of Bethulia (both 1914), he had impressed viewers with works of a defined aesthetic density far above the run of mostly mercenary amusements. Griffith developed himself as a brand, and when he premiered his new film, he showcased it with a costly roadshow presentation and charged the then-exorbitant amount of $2 a ticket. Perhaps The Birth of a Nation is more a landmark in the annals of hype.

.

.

Still, what about the actual film, the relic shining out from under all the rhetorical dust? Does it still shout out its storied power above the din of its controversy? Yes and no. Even without taking on the sorry race portrayals, The Birth of a Nation is a mixture of the crude and the fine. Portions are undoubted displays of great cinematic effect and art, whilst others drag and slouch. The plotting is naïve and occasionally confused, the acting uneven. At times it’s a stock-standard melodrama of the kind readily found in turn-of-the-century novelettes and stage plays, complete with rosy-cheeked damsels in distress, lascivious villains, good-hearted patriarchs, and bellicose mammies. The characters it describes aren’t really people, but are mostly archetypes of a bygone society’s best self-image and basest anxieties.

.

.

The first third of The Birth of a Nation is still a vivid creation for all the qualifications, tethering the microcosmic, presented via the families of congressional leader Austin Stoneman (Ralph Lewis) of the North and Dr. Cameron (Spottiswoode Aitken) of the South, with the macrocosmic drama of erupting civil conflict. Stoneman upholds radical abolitionist policies, partly under the influence of his black housekeeper and mistress Lydia Brown (Mary Alden). In spite of brewing war clouds at the time of Lincoln’s election, Stoneman’s sons Phil (Elmer Clifton) and Tod (Robert Harron) visit their friends the Camerons, whose ranks include sons Ben (Henry B. Walthall), Wade (George Beranger), and Duke (Maxfield Stanley), and daughters Margaret (Miriam Cooper) and Flora (Violet Wilkey), in their South Carolina town of Piedmont. Ben falls in love with a photo of Stoneman’s daughter Elsie (Gish) given to him by Phil. The settled life of the Camerons, the bustle of household work, the roughhousing of the sons and the scampering of the kids, the quiet reclining of Dr. Cameron, is quickly and skilfully sketched by Griffith in the midst of the decorous, homey beauties of picket fences and rose bushes. The Stonemans also get a tour of cotton plantations, where slaves labour and readily dance gleefully for the visitors. Just after the Stonemans depart, Lincoln (Joseph Henabery) signs his call for volunteers, “using the Presidential office for the first time in history…to enforce the rule of the coming nation over the individual states.” War breaks out, and the Cameron sons join the Confederate cause.

.

.

Griffith builds these sequences, shifting from the bucolic to the ecstatic, with gathering force, capturing the mood of being swept up in what its characters see as a great, romantic, classical quest. Bonfires and dancing greet the news of war. “While youth dances the night away, childhood and old age slumber,” a title card notes, as the camera studies the snoozing Dr. Cameron and Flora, establishing a quality of dialogue, the existence of separate modes of life even within the frame of a single story. Griffith’s framings are often studied and still resemble the static state of much early filmmaking: his sequences often tend to comprise a few basic compositions, alternating between them. Two crucial aspects, however, imbue them with an uncommon life: the frames are packed with detail, often with Griffith pushing his actors to be in constant movement and expression in relation to each other, usually with elements arranged along diagonal axes to give the square frame depth and a definite dramatic quality. Griffith’s characters often look as if they’re perching on the edge of something, as in early scenes where they hover amidst the columns of the Cameron house, whose design splits the difference between Antebellum manse per Confederate mythology and normal suburban villa to which more of the audience could relate. Most vitally, Griffith cuts constantly, giving his moving pictures the same sense of velocity and a fluidic, implicit sense of relationship, rather than a flatly grammatical one. The depiction of Piedmont’s soldiers heading off to war thrums with a sense of motion and pictorial eloquence–the gyrating crowds in the town square and columns of parading soldiers, the lasses bedecked with flowers and the horses similarly garlanded, the young gallants stealing kisses before riding off, Ben teasing “pet sister” Flora by dangling the Confederate flag over her face as she naps, and the familial pietas of soon-to-be-bereft loved ones waving farewell. Billy Bitzer’s photography, justly celebrated as a grand technical achievement, is constantly striking, particularly the night sequences of bonfire celebrations. Griffith foreshadows with witty asides. A young kitten and pup, pets of the Camerons, tumble into each other and commence what is described as “hostilities” by the title cards.

.

.

The wartime sequences are even more impressive for the sense of rolling, panoramic drama. Freed from having to relate the audience to actors at the centre of focus and understanding, Griffith pulls off coups of pure visual power, covering fields of battle and scenes of history purely according to the needs of his camera rather than the call of an imagined stage, letting his images flow in a manner reminiscent conceptually of book plates and theatrical pageants, and sometimes based outright on artworks, but imbued with the illustrative force of cinema. One of the Cameron sons catches a bullet during an infantry charge. Tod Stoneman dashes in, ready to bayonet him, only to recognise his friend and stay his hand, moments before a Confederate bullet cuts him down in turn: Tod collapses, pulling his friend close and dying, leaving them entwined in a brotherly embrace. This vignette is trite on one level, and yet also a concise, visually powerful encapsulation of Griffith’s message regarding war, as direct and intelligible as anything in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Another Cameron boy dies during the retreat of the army. The burning of Atlanta is depicted in a crude but startling proto-matte shot, in which extras amidst life-size sets swathed in smoke reel underneath a burning model of the town. A long shot of Sherman’s army on the march through the countryside filmed from a hilltop sees the camera pivot to note a mother and her children looking on, an iris effect zeroing in on them before Griffith cuts to show us their faces beholding the annihilation of their world: the victims of war are privileged by the perspective Griffith takes on them over the distant, anonymous mass of men.

.

.

The most spectacular war sequence is set in the waning days of the conflict, where Ben Cameron, now beloved by his men as “The Little Colonel,” leads them in an attempt to break out of siege for supplies, only to be held off by Union soldiers commanded by Phil Stoneman. Ben stirs the admiration and then the cheers of his enemies by first helping a wounded Union soldier and then by defiantly dashing across no-man’s-land and jamming the pike of the Confederate battle flag into a Union cannon. Here Griffith wields but also varies a clear sense of geography, via the battlefield framed like a football field with the opponents on either side, studied first in high vistas and then long group shots, and then close studies of individual actions. At one point, the camera charges with Ben and his men, and the sequence builds to the shot of Ben at the cannon filmed from behind the cannon, capturing the pain and heroism of the gesture. This is all utterly familiar filming and editing method today, but represented the cutting edge of sophistication at the time, and moreover still shines with the peculiar intensity of real creativity. One can still almost share the effect that shot of the cannon spiking must have had in 1915, the animate drama and sensatory power of watching an actor, some sets, crew, and a strip of celluloid interact and be manipulated until it seemed as if the essence of life and death have been depicted. Whilst such oversized vignettes dominate the impression The Birth of a Nation leaves, the film is replete with testaments to the value of small gestures and fleeting, but vital, observations as part of the overall texture. There’s the droll humour of Stoneman letting Elsie fit the wig that conceals his bald pate and a guard in the military hospital sighing over Elsie’s untouchable beauty, and a purposeful linkage of images adding up to ideas, as when Ulysses Grant (Donald Crisp) and Robert E. Lee (Howard Gaye) shake hands at Appomattox, followed immediately by Ben and Elsie doing the same.

.

.

Griffith synthesised all of this for his own satisfaction, his own family’s part in the war perhaps lingering in the vividness with which he describes the struggle as well as a sense of discovery, the first poet of a new form to describe such a vista. Tellingly, most of what comes later in adapting Dixon more directly is lacking from this part, though early scenes are interpolated depicting Lydia Brown’s Uriah Heep-like patronisation of Stoneman’s Senate opposite Charles Sumner (Sam De Grasse), alternating with her fire-eyed tantrums motivated by her evident desire to be loftier, a desire she later realises as her hold on Stoneman becomes unshakeable and she begins contemptuously ushering Sumner away. Lydia is described as using her power over Stoneman to ends that will have dire consequences, though how and why, beyond pure wilful egotism, isn’t quite described; in any event, Stoneman uses Lincoln’s assassination to begin a forced social revolution in the reconstructing states after the war. Stoneman and Lydia were clearly based on Thaddeus Stevens, leader of radical Republicans, and Lydia Smith, his housekeeper who was probably also his mistress; The Birth of a Nation implies that this fatal act of miscegenation set the stage for civil war. One revealing aspect of Dixon’s paranoid racism captured in the film is how one could easily tweak this to make it seem heroic (as Steven Spielberg would when depicting Stevens and Smith in Lincoln, 2012), in the theme of the oppressed and disadvantaged released from their shackles and using new-found power to redress the moral books, an idea which The Birth of a Nation cannot countenance, and instead hides behind mendacious suggestions that it was rather the quintessence of duplicity and anarchy.

.

.

At the same time Griffith dissembles, referring to certain villainous black characters as “traitors to their own race” as well as to the larger nation, though the film infers that because of the bad actions of these specific wrongdoers, all must be subjugated. A clue as to how confused The Birth of a Nation is, politically speaking, is found in its treatment of Lincoln, who is described early on as trampling on states’ rights, as per Dixon’s outright Confederate propaganda, whilst his determined attempts to force the abolition of slavery are avoided altogether. (One scene purportedly cut from the remaining print after early screenings depicted a gang rape of a white woman by black soldiers with the title card “Lincoln’s solution.”) But the film also plays up the more familiar, positive image of the leader when it suits. When Mrs. Cameron (Josephine Crowell) goes to visit her son Ben in a Union military hospital, she learns he’s going to be shot, so she goes to see the President to beg for his life, and he grants her request.

.

.

When Lincoln is killed, Dr. Cameron laments that “our best friend is gone.” The depiction of Lincoln’s assassination is a masterly set-piece from Griffith, perhaps indeed the strongest sequence in the film. Rather than merely present the famous moment as tableaux vivant, Griffith instead depicts events with a flow of documentarylike detail, generating suspense with analysis of the mechanics of the act. He notes Lincoln’s bodyguard setting himself up in the hallway outside his theatre box, but then being drawn into another booth to take a look at the play. This gives John Wilkes Booth (played by future director Raoul Walsh, who was also the husband of Miriam Cooper at the time) the chance to storm the box, his act of violence and flying leap onto the stage and infamous cry of “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” delivered at concussive speed, capturing the deliberately theatrical power of the assassin’s deed. Booth’s showmanship suits Griffith’s, whilst history weaves in with fiction: Elsie and Phil Stoneman are in the crowd, and see the whole thing, whilst the President’s murder gives Austin Stoneman his chance to push his agenda unfettered.

.

.

One rarely contemplated aspect of The Birth of a Nation is one it shares with much of Griffith’s cinema: women were at the centre of his movies, and in many ways he helped codify the “women’s picture” with his tales of oppressed waifs, degraded mothers, and plucky gamines who soldier through trials. Whilst in hospital, Ben meets the object of his abstract obsession in the flesh, as Elsie Stoneman is working there as a nurse: Elsie forms a bond with Ben and his mother and helps her make the plea to Lincoln. The framework of Dixon’s story demands the ladies chiefly be used as threatened victims, and Griffith was always happy to serve up images of decorously beautiful young women audiences of the time loved. But Griffith emphasises the moral force of motherhood and the determined energy of the young women. Elsie, Margaret, and Flora are all as active in their way as the menfolk, absent from the battlefield, but guarding the gates of civilisation and dodging the predations of the age, as when the Cameron girls and their parents have to hide in their household cellar to avoid marauding Union soldiers in Piedmont.

.

.

One early shot captures young Gish’s mischievous screen quality and Griffith’s feel for actors, as she sets her brother racing off and then skips and jumps her way back toward the Stoneman manse, all distracted and tomboyish energy even as she clutches a kitten and looks entirely winsome. Both Elsie and Margaret hold off the men who romance them because of their ethical dimensions: Elsie holds loyal to her father’s creed when she realises Ben has become involved with the Ku Klux Klan, and Margaret refuses Phil’s overtures in memory of her slain brothers. By comparison, the male characters, apart from Ben, are blank slates, operating robotically according to assigned identities, from the young men signing up for state-sponsored carnage to the black and half-caste characters for whom the sexual conquest of a white woman is both their most verboten and most desired object.

.

.

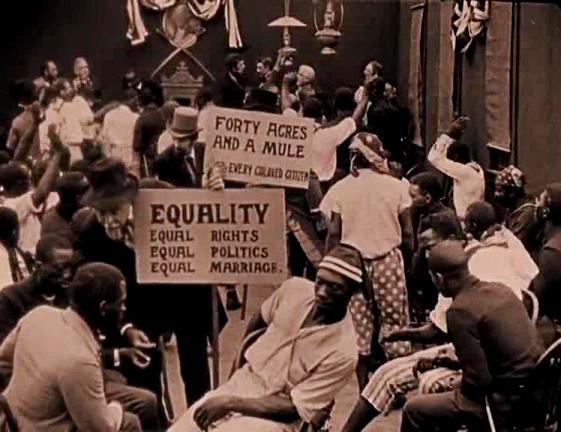

As The Birth of a Nation moves into its second half, the focus shifts from war to fractious peace. It’s here the film becomes truly difficult, to say the least, both in terms of art and meaning. Griffith’s freeform exploration of the Civil War gives way to a more settled, straightforward adaptation of Dixon’s novel. Austin Stoneman relocates to Piedmont with his remaining children to oversee the Reconstruction programme being carried out by a horde of soldiers, carpetbaggers, and freedmen. Stoneman’s protégé is the biracial Silas Lynch (George Siegmann). The congressman gets him installed as lieutenant-governor with the aid of a rigged election where local citizens are refused participation whilst manipulated ex-slaves vote. All of this, the title cards inform, creates a state of lawless anarchy in the district, though little of this anarchy is actually depicted. What we do see is Ben Cameron taking inspiration from seeing a couple of white kids scare some black kids by hiding under a sheet and having the brilliant idea of applying the same principle to his brainchild. He creates a militialike force to strike back at the corrupt and chaotic regime and newly free black citizens seeking their rights without exposing themselves to reprisals: the Ku Klux Klan is born. Meanwhile, Lynch becomes increasingly megalomaniacal, believing he can use the black soldiers under his command not just to bully and oppress the Southerners but to carve out a kingdom that he will rule. He wants Elsie to be his queen, and looks for a chance to corner her, though she clearly prefers Ben. The situation comes to a head when one of the black soldiers, Gus (Walter Long), stalks Flora (played as a grown-up by Mae Marsh) with rape on his mind through the forest outside of Piedmont. Rather than submit, she jumps of a cliff. The Klan avenges her death by tracking down and lynching Gus. Lynch responds by threatening anyone proven to be participating in Klan acts with hanging. When Ben’s Klan costume is found in his house, what’s left of the Cameron family is arrested.

.

.

The Birth of a Nation’s pretences to creating a Homeric epic of America hinge unavoidably on a slanted portrayal of events that are still somewhat ill-served by film: there is a void in cinematic depictions of the Reconstruction era, and many that do exist take a similarly Southern point of view. Perhaps, as Buster Keaton said a few years later, when he made a Confederate his hero in The General (1926), that’s because it felt unfair to many to kick the losers much more. Gone with the Wind, the film’s immediate successor both in subject and success (and another work almost certainly influenced by it), bent over backwards to avoid Griffith’s mistakes, but created some thorny issues of its own. If there’s a salutary value to the way The Birth of a Nation depicts the dankest, sleaziest, most perverse fixations of a certain brand of American bigot, it is that it properly recorded them for posterity. This allows anyone with an ounce of intellectual honesty to see the way the ideas propagated here still define many of its precepts before various masking tactics were adopted–that black men are essentially lascivious, violent apes waiting for a chance to sexually assault white women and brutalise their menfolk, that attempts to reapportion social justice for African-Americans after the war and even today only facilitate the first point, that vigilante justice by gun-toting “ordinary” people is the only force that can stop it, and so forth. In spite of the film’s controversy at the time, there was nothing particularly uncommon about the historical thesis proposed: even President Wilson, a high-minded idealist in many regards, was also a deeply racist thinker whose writings on the topic of the Klan influenced Griffith’s presentation of it. “The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright,” a title card says late in the film when two former Union soldiers aid the Camerons in fending off the black soldiers stalking them, a line that’s deeply depressing but also perfectly revelatory.

.

.

One of Griffith’s most brilliant flourishes, a highlight of inspiration in the second half, is woven in inescapably with racist pseudo-history: a shot of the state legislature, empty at first, transitions to a later time when the house has been filled with rowdy freedmen serving Stoneman’s political program. This is another moment one can well imagine stunning an audience in 1915. Dissolves, superimpositions, and double-exposure effects had been used before, but Griffith uses them here to create an active, purely filmic device of satirical insight, albeit a vicious, wrong one. The installed black legislators make a mockery of the solemn institution by drinking whiskey, kicking their shoes off, and generally look like they’re having a good time in a way that’s actually not so far from the Marx Brothers’ similarly anarchic treatment of such settings–except by the 1930s anarchy, at least that plied by impish white guys, was cool. One real crux of the quandary The Birth of a Nation presents is that such sensitivity as Griffith often displays can coexist with such unregenerate contempt, in the process of watching art foiled by prejudice. Perhaps the lowest point of this fantasia comes in the concluding scenes when the Klan, having restored justice and order, keep black voters from going out to vote, presenting the beginning of the century of marginalisation and depression codified under the Jim Crow regime as a heroic, even funny vignette in the film, evident in the way the black would-be voters reel out of the bars, see the hooded, armed Klansmen outside, then promptly swivel and retreat. This moment is as despicable as anything I’ve ever seen in a film.

.

.

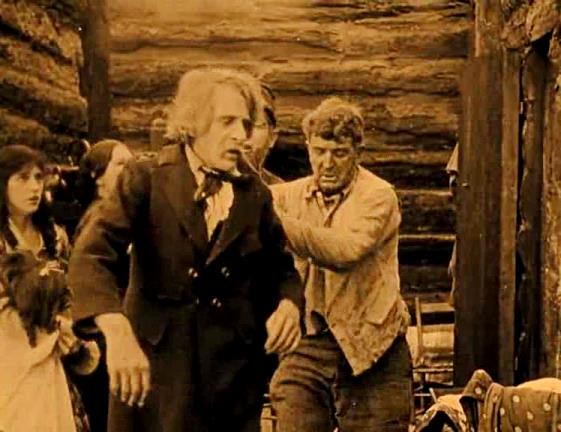

Ironically, most of the black roles are played by white men in blackface. Roger Ebert proposed this was because staging some of these images with real African-American actors would have been too incendiary, but perhaps it was to avoid production conflicts. In any event, the ridiculous look of these performers gives much of the film the quality of grotesque pantomime, accidentally highlighting the artificiality. The Reconstruction chapter has often been celebrated in spite of all this for exemplifying one of Griffith’s great innovations, as he cross-cuts between sectors and streams of action: the Camerons, who escape their military escort and face siege in a remote shack, Lynch in Piedmont taking Elsie captive for a forced marriage, and the Klansmen gathering and charging to the rescue. The second half, however, often feebly executed by comparison with the first, moving stolidly through its relatively few substantial plot points, with many elements left vague, like Lydia Brown’s fate. Amidst shoot-outs and rescues, the true climactic moment comes when Lynch tells Stoneman that he wants to marry a white woman. Stoneman congratulates and encourages him, but then when Lynch tells him that he specifically wants to marry Elsie, Stoneman erupts in outrage. This could easily be tweaked as a moment of satirical insight, making fun of a shallow form of white liberalism that’s perfectly okay with anything in abstract, and indeed it is after a fashion. But it’s also intended as both revelation and comeuppance for Stoneman, who is forcibly shown the logical end point of his politics, and reacts with the same natural repulsion, the storyline implies, any father would in the face of such depravity.

.

.

Much of the plotting here is, again, standard melodrama, with Dixon’s bullshit pasted over already very familiar roles and rituals of penny dreadful villainy. What’s new, however, is that stuff is matched here to a show of filmic technique that thrilled the audience of the day and gave unto later filmmakers a blueprint of how to achieve the same result again and again. Yet it also laid the seed of warning for followers, too, in seeing just how easy it could be to follow a programme of storytelling in the new medium that could manipulate them into siding with monstrosities. The famous ride of the Klan proves rather slow and arthritic for a contemporary eye, however. Radical as such technique was, there was still a long way to go in giving this gimmick the kind of rhythmic intensity it could wield. There are some eye-catching compositions, like the Klansmen riding silhouetted against the sky on a ridgeline, but the interpersonal scenes of Stoneman and Lynch arguing and the Camerons and their comrades in the shack returns to flat, two-dimensional framings. Lynch, if he wasn’t so set on marrying Elsie and arguing with her father, could have ravaged her a dozen times by the time the Klan actually reach Piedmont. Griffith would push his new technique much farther in his follow-up Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout The Ages (1916), where he cross-cuts not merely related but separate scenes, but whole storylines and timeframes.

.

.

Near the film’s very end, Griffith recaptures his visual invention as he shifts into symbolism and surrealism through visuals that evoke medieval artistic styles and literary pictorial plates: a diptych of War on horseback waving its sword over a pile of corpses, and another of Jesus reigning over a court of the faithful. Here, the feeling of cinema as art form as well as populist political sentiment are both revealed as perched on a wickedly sharp edge. Film is gaining its method and its voice at the same time as it is emerging from the influence of other art forms, and an accumulated system of meaning depending on assumptions that cinema perhaps served in part as a stronger beam of sunlight than had ever been seen before. The profound contradiction between the film’s ardent statements of pacifism and brotherhood and its equally ardent preaching of fascist, racialist hegemony is strange as well as appalling to me, as if in that disparity, if only one can grasp it, lies the seed of so much that would transpire in the 20th century. The past had been neatly reconfigured into a myth, but already new realities were pressing, begging their own mythologising.

.

.

The Great War was raging across the Atlantic when the film was released, and surely on Griffith’s mind as he questioned “Dare we dream of a golden dawn when the bestial War shall rule no more?” in one of the film’s last title cards. So, naturally, soon the Hun would be serving the same purpose black men had in warmongering movies. At the same time, black Americans could see what many thought of them all too clearly, and found that could be a weapon that cut two ways. Griffith himself would be elevated to the stature of god-king of an art form for a short reign, but at the same time was hurt and bewildered by the forced realisation he had created something deeply troubling. He would take up the themes of prejudice, abuse, and other pressing social problems often thereafter, struggling with films like Intolerance, Broken Blossoms (1919), and The Struggle (1931) to come to grips with such issues. He would fail politically and commercially, but grow poetically. The conflict between this sense of achievement and the urge for atonement would define the rest of Griffith’s career.

A finely detailed examination of this film, Roderick. However, it was not actor-producer Edward Burns, but Ken Burns who did the landmark Civil War documentary miniseries. Otherwise, bravo.

LikeLike

Urgh, how the hell did that happen? Thanks for spotting, Leopard.

LikeLike

One of the best reviews I’ve ever read of this film, simultaneously (if only partly) an artistic triumph and one of the most despicable, atrocious pieces of propaganda ever created. I especially appreciated your analysis of Griffith’s subtlety, the beautiful small gestures that are just as important as the director’s epic scope and technical innovations even though they are frequently overlooked. Yet in the grand overview of his career – at least those works presently available – it’s the attention to detail that characterizes him more than the scale of his vision.

Aesthetically, I’ve often felt that same dichotomy you describe above: between the sensitivity of the first half and the crudeness of the second, as if the blunt bile of the Reconstruction material actually sapped some of Griffith’s creativity in a way the less plot-driven, more contemplative antebellum and war sections did not. Learning that the second half was a closer adaptation of Dixon’s novel than the first explains quite a bit of that. I’m always fascinated by the ways a director’s vision interacts with his or her source material, overcoming it, falling prey to it, at times existing side-by-side in uneasy juxtaposition. As you say, Birth of a Nation remains valuable because of how undisguised its ideology is, and how forcefully it confronts us with film’s ability to sugarcoat sickening lies. As I once put it, it inadvertently uses the Reconstruction era to deconstruct itself. In that sense, at least for modern audiences, it’s a more upsetting but less pernicious viewing experience than, say, Gone with the Wind.

LikeLike

“Birth of a Nation” is really good in the Civil War segments, after which, oh my. Griffith clearly sympathized with Lincoln, which makes me skeptical of ‘One scene purportedly cut from the remaining print after early screenings depicted a gang rape of a white woman by black soldiers with the title card “Lincoln’s solution.”’ If it actually existed, Griffith would have cut it, not only on grounds of taste, but because it contradicted his own views of Lincoln (who he later did a biography of).

One thing I noticed is that the chief villain is a mulatto, and Stoneman and Lydia’s misegenation is a major plot point. It’s not so much that the movie is anti-black, but that it’s against mixing of the races. And, naturally, that the blacks should go back to Africa, to prevent this horror.

This is a hard film to watch. I’d like to see someone do a straight historical film with the characters having the same names as the characters in this film.

I’ve always thought “Julith of Bethulia” or “The Avenging Conscience” was Griffith’s first feature film; more the latter, since “Judith” is structured more like a short film, while “Conscience” is structured like a feature. “Musketeers” is really good, and reveals Griffith was a pioneer of gangster fims. “Conscience” shows him as a pioneer of horror films.

LikeLike

Hi Joel, Syd. Glad you enjoyed this piece. It is surely a fascinating and galling relic, and as unhappy as it made me often — the moment when Gus’s body is left on Lynch’s doorstep with the KKK message pinned to it made me genuinely angry and physically ill — I’m still glad I finally had this experience. To be frank, I find something like Cold Mountain, which is set amongst Confederates but engages slavery not at all, to be most pernicious — boutique history! All the romantic thrills, no discomfort! But I digress. I do think Griffith wasn’t terribly interested in Dixon’s novel per se, and it shows through with the relatively half-hearted filmmaking in that section. But I also think Griffith bought into its thesis sufficiently to make him highly culpable. Perhaps the best thing that can be said for him is that he was one of the people who learnt a lesson from the fallout. I suspect he was too much a sentimentalist, buying into the dramatic orientation of any narrative sold to him. Indeed, to a certain extent this is not really one movie; there are several mini-narratives within it; the Lincoln assassination could be a movie in its own right. Indeed, as you note Syd, miscegenation is a predictably thorny issue in all this, with the implication that biracial people inherit the worst traits of both races, the implication that they constitute an enemy within. The cut scene is documented (although some sources say that the “Lincoln’s solution” was actually attached to a postscript about deportation to Liberia) and as I’ve said I don’t think the film’s take on Lincoln is that straightforwardly positive. The film is however a jumble on the political and historical level, and I think that lack of a clear dramatic programme on Griffith’s part contributes to this: some parts probably sprang right out of his mind, others drawn from a quick consultation of the book. I do certainly agree it would interesting to see a more modern and exacting take on the history here. The upcoming film that has wryly stolen the title concentrates on Nat Turner’s rebellion, which means it’s not quite the same, but certainly a worthy subject nonetheless. Anyway, love your comments on earlier Griffith, Syd.

LikeLike

Griffith also did several shorts about Native Americans which tended to be sentimental. It’s been a while since I looked through his short films, but it was an interesting experience.

LikeLike

Yes, I’ve seen one of his early shorts which as I recall dealt with a love triangle amongst fishermen. It was pretty trite, sadly. That was before a screening of The Sorrows of Satan, which is intermittently very striking but also a frustratingly lumpy experience because of the painfully naive storyline and Griffith’s inability to feel his way around leftover Cecil B. DeMille material.

LikeLike