.

Director: Ridley Scott

By Roderick Heath

Mars, the near future. The members of Ares 3, the third manned mission to the Red Planet, pick at the surface whilst pursuing their scientific mission. The team consists of commander Melissa Lewis (Jessica Chastain), pilot Rick Martinez (Michael Pena), and a crew of highly competent supernerds, Mark Watney (Matt Damon), Chris Beck (Sebastian Stan), Beth Johanssen (Kate Mara), and Alex Vogel (Aksel Hennie). As Watney and Martinez trade their practised acerbic banter, the team are called in because a powerful sandstorm is heading for their mission base. Rather than weather out the storm and risk the safety of the rocket that will take them off the planet, Lewis orders the mission aborted and immediate evacuation. During the near-blind and floundering trek through the storm to the rocket, Watney is struck by a piece of flying debris and flung into the maelstrom. Lewis tries to find him but, faced with the evidence that he’s probably dead, and with the rocket in danger, she gets aboard and orders lift-off. The accidental tragedy, the kind that can befall such dangerous missions, is reported, and NASA boss Teddy Daniels (Jeff Daniels) breaks the sad news to the world’s press.

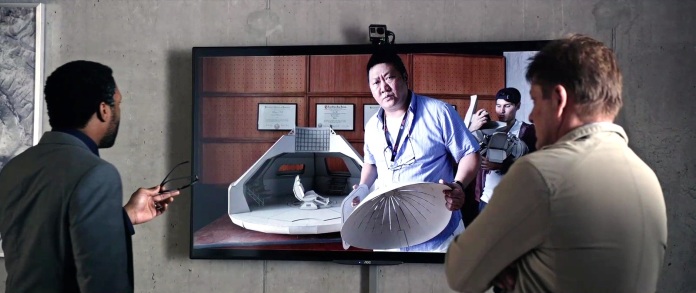

Watney, however, is not dead. He awakens half-buried in the red Martian soil, a steel spike jutting from his chest, his pressure suit leaking but not enough to kill him. He manages to get back to the habitation unit, dig the jagged metal out of his body, and staple the wound closed. He is then confronted by the awful fact of his situation: the smart-aleck botanist and engineer knows he’s alone on Mars, his communications wrecked, and the rations left behind insufficient to last him the wait of up to four years until the next mission arrives. Watney must improvise the best he can with the limited tools available to him, the limits of his existence reduced to a glorified tent on an alien alluvial plane. There’s nothing left to do but, in his words, to science the shit out of this. Watney is presumed dead by everyone on Earth for many months, and his survival is only discovered by accident when the NASA director of operations, Vincent Kapoor (Chiwetel Ejiofor), asks permission to scan the site of the Ares 3 mission by satellite to check its condition. Technician Mindy Park (Mackenzie Davis) quickly discerns that someone is driving around the abandoned rover vehicle.

Daniels refuses to pass on the news to the Ares 3 crew, who are already grieving his loss, but NASA snaps into gear to work out how to resupply Watney in a tight window of opportunity. Unexpected disasters soon begin to make the situation critical, as Watney’s crop is destroyed by a near-fatal rupture in his airlock, and the first rocket built to send food to him crashes during launch because of its hurried construction. The head of the Chinese space agency, Zhu Tao (Chen Shu), offers to help with his organisation’s new experimental booster rocket, but a young telemetry expert, Rich Purnell (Donald Glover, stealing scenes), has a better and less risky idea, and proposes turning the Hermes, the spacecraft used by the Ares crew, around and sending them back to fetch Watney after a resupply. Teddy nixes the idea, not wanting to risk the rest of the crew, against the heated disagreement of Mission Controller Mitch Henderson (Sean Bean), so Mitch secretly transmits Rich’s plan to them, essentially making it their call whether to turn around and trek back across space to save their friend. Meanwhile, Watney survives his ordeal with the only supply of Earthly culture left behind for him: Lewis’s USB collection of ’70s sitcoms and disco music.

Andy Weir’s 2012 novel The Martian had a very contemporary genesis. Weir, after dabbling unsuccessfully as a writer, started the story as a blog purely to amuse himself, but then the project developed much like the adventures it portrays: a solitary task that attracted like minds fascinated by the same ideas and problems Weir postulated. The ideas readers contributed via comments were woven into the tale. Weir placed most of his emphasis on the science part of science fiction, striving to create a believable depiction of survival on another planet. Weir’s narrative template was obviously Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe: as with Defoe, the nuts-and-bolts survival methods of a castaway concerned him first and foremost, tackling in abstract the very real and likely problems of survival as a mixture of thought exercise, best-practise thesis, and classical frontiersman narrative. For dramatic convenience, Weir eventually brought in other characters and viewpoints, including a collective of NASA brains and Mark’s own guilt-ridden crew. Weir’s novel was deliberately (in part) artless, most of it presented in the form of Watney’s daily log that suited the initial presentation on a blog perfectly whilst also reviving an old literary form, the epistolary novel. Watney’s yammering, authorial voice was replete with pop cultural references, sophomore sarcasms, and nerdy enthusiasms—pretty much the voice we’re all used to reading on a thousand fliply amusing websites. The blend of hyper-detailed procedure and antiheroic humour wasn’t great drama or deep contemplation, and yet it made for a very enjoyable read.

Ridley Scott’s film adaptation was destined to be a rather different creature, though screenwriter Drew Goddard, who handled the witty, if minor, horror genre riff The Cabin in the Woods (2012), follows the novel scrupulously in many regards. Scott, one of the few great maximalists left in cinema, couldn’t be much different to Weir in his approach to his art. But it’s not difficult to discern the appeal of the material for the director. For one thing, it lets Scott operate in several genres at once, most of which he’s tackled before, particularly in his restless late career. It’s a scifi vista about fighting for survival a la Alien (1979); a comedy about characters with weak social skills like Matchstick Men (2003) and A Good Year (2006); an epic pitting man against primal forces following on from Prometheus (2011) and Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014); and a tale of a searcher founding new worlds like 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992) and Kingdom of Heaven (2005).

The sequence in which Watney operates on himself suggests a prototype for Prometheus’ best scene, which depicts more sophisticated self-surgery. Prometheus was doomed to stay in the shadow of Alien because of a confused screenplay, whilst it also discomfortingly revealed how much more staid and lumpen much current big cinema often is compared to that from the days when Scott emerged. The mild disappointment of the experience seems to have stung Scott out of a relatively flat period. The Martian, excellent as it is, might also count as a decline from the gutsy strangeness of The Counselor (2013) and the epic vigour of Exodus: Gods and Kings, two films with completely diverse brands of ambition that few seemed willing to process. Most vitally, though, The Martian allows Scott a chance to approach narrative entirely on the level of systematology, a notion he’s been dabbling with for most his career but started reflecting most seriously on his underrated crime movies American Gangster (2007) and The Counselor. In those films, he strove to do what most gangster flicks avoid and demonstrate the drug industry as a chain of cause and effect leading right down from kingpin to the most pathetic junkie. Even more impudently, he used a spectacular chain of logically metastasising events to illustrate that most illogical of things, divine intervention, throughout Exodus: Gods and Kings.

Watney is Scott’s anti-Moses, and yet echoes his take on the mythic hero, partly signalled by Scott’s return use of Wadi Rum in Jordan as a location for the drama (whilst also tipping his hat again to Lawrence of Arabia, 1962, which also used the same location). Watney is forced to rely purely on his own invention, using happenstance advantages, like the manna provided for him in a package of potatoes shipped for a Thanksgiving feast that gives him the chance to grow enough crops to live, and then carefully manufacturing what he needs, including water, through risking chemical and mechanical processes. Weir’s book was obviously far more detailed and in-depth about the pure process of this undertaking, and to a certain extent Goddard’s script skates over the very business that is the essence of the tale. But then The Martian is a mass-market movie, and it’s already stretching the template by avoiding many regulation elements and clichés—only the very faintest hints of romance, little action, very little religion, and a bunch of eggheads for protagonists.

The Martian’s can-do poptimism strikes a refreshing note in the contemporary film landscape, following Weir’s lead in contemplating a situation where scientists get on with their jobs without political interference and the world’s populace looks on, riveted by the spectacle of how to do a lot with very little—a very now theme if ever there was one. The Martian belongs to a recent string of science fiction straining to be more accurate than the cinematic branch has often been seen as in the past, whilst also connecting to hallowed works of the genre’s history. The speculative problem-solving has roots not just in Robinson Crusoe but also in Jules Verne’s template of blending hard and soft science based in the best available knowledge and cutting-edge concepts of his time. Cinematically, Byron Haskin’s Robinson Crusoe in Mars (1964) is an obvious intermediary: Haskin’s film dragged in scientific improbabilities, like stones that give off oxygen when heated, and the outright fantastic, when aliens eventually appear. But it also evoked an eerie, distinctive, dislocated mood that anticipated the serious science-fiction filmmaking of the next two decades, including Alien. Haskin had worked long before that with George Pal, who had produced Destination Moon (1950), the first modern scifi film and one that was just as persuasively preoccupied with the true problems of space travel. Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars (2001), a controversial flop at the time of its release and another film made in the image of Stanley Kubrick’s tirelessly (and, increasingly, tiresomely) influential 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), helped reinvigorate realistic scifi with its elegant use of the authentic limitations of travelling in space, usually sidestepped readily by filmmakers, as the very matter of its drama—the danger of meteors, the tyranny of distance and scarcity, the exacting punishment attending the smallest of faults and miscalculations.

More recently, Gravity (2013) and Interstellar (2014) had delved into similar territory (The Martian shares Interstellar cast members Damon and Chastain). One thing The Martian has that those films conspicuously lacked is its scallywag sense of humour; Scott’s film is less pretentious than either whilst going well past them in actual, practical acumen. If it lacks the intermittent glimpses of unusual grandeur Christopher Nolan conjured in his work, it also avoids the bad wobbles of story and characterisation, and actually lives up to the promise of convincing use of a far-out setting on which Gravity failed so conspicuously to deliver. But actually, a closer ancestor to Weir’s novel was The Andromeda Strain (1970), Robert Wise’s adaptation of Michael Crichton’s novel where almost all of the drama was found specifically in scientific exegesis. A lot of Weir’s more finicky process details are left out of the film, and Scott is more attentive to the physical level: Watney, as his ordeal continues over months, degenerates from a man blessed with Damon’s weathering but still very boyish features and sturdy physique, to scrawny, sore-riddled, malnourished remnant sprouting a ragged beard. Scott’s filmmaking is part of the great pleasure of The Martian: avoiding much of the mannered and assaultive lexicon of contemporary pseudo-realism (some of which Scott helped invent), Scott instead offers a work of classical filmmaking sweep, perhaps his most successful attempt: it somehow manages to be at once fast-paced and dashing, yet also curiously relaxed, a work of profoundly casual skill.

The filmmaking here is most memorable when regarding the Martian landscape itself, a vista grand and beautiful, but also utterly desolate. Watney’s journey across the planet to locate the escape ship intended for the next mission but now to be repurposed as his ark is an interlude of cinematic grandeur that again nods to Lawrence of Arabia’s Nefud Desert crossing sequence, alternating viewpoints both godlike and eye-level. Some have called Scott’s approach to the material distant, but I found it simply elegant, and perhaps that’s so rare these days, no one recognises it. The mix of old-school cinema and new-age humour, potentially awkward, works for the most part. Perhaps there was the seed of something shaggier and more genuinely oddball here, in the mould of John Carpenter and Alien collaborator Dan O’Bannon’s heady Dark Star (1974). But of course, that was never part of the mission statement. Weir resisted introducing much introspection on Watney’s part, with the suggestion that Watney’s detail-focused approach to his situation holds at bay existential angst. One of the best jokes transcribed here satirises a tendency towards heavy metaphysical ponderings in such fare, when Kapoor wanders what Watney must be thinking, before cutting to the stranded astronaut deploring the lyrics of disco music.

Scott, on the other hand, whilst not trying to graft something too weighty onto the material, doesn’t let Watney escape unscathed, simply utilising his filmmaking to acknowledge a sense of isolation and the tug of eternity, and finds a sense of wonder as much in the miracle of a sprout of living green, with all its scientific and poetic meaning, as in the vast reaches of an alien world. Watney is confronted with a landscape of perfect solitude, his status as pioneer, the first one to go just about anywhere on the planet, a space cowboy and tourist who has the technology-provided ability, familiar again to most of us these days, to define his own reality with the music he constantly blasts, and yet with the tug of airless infinities just beyond his cocoon of plastic and digitised music.

Scott and Goddard smartly dial back on some of Weir’s more awkward, populist-wannabe touches, like the clashes of temperament between Teddy and Mitch, aiming more for an interesting diminuendo where a confrontation of the two men after Mitch makes his risky play acknowledges consequences like grown-ups. It’s tempting, indeed, to read Mitch, with Bean in the role dampening his trademark machismo and playing up his intelligence, as Scott’s avatar in the film, a man long used to playing by a larger game’s rules but willing to occasionally remind everyone he doesn’t always sign on with the smooth, hierarchical, technocratic suppression of human instinct (Bean’s presence also presents an opportunity for one great in-joke for Lord of the Rings fans). I was also pleased that Chastain, who might have been prodded to overplay the fearless leader in a manner close to her charmless part in Interstellar and her steely-neurotic spymaster in Zero Dark Thirty (2012), instead offers a portrait in mature leadership that, again, feels rather rare in recent filmmaking. Chastain expertly handles the moments like when she holds herself accountable for leaving a very-much-alive Watney behind with pliant skill, registering both piercing reprobation and lucid realism. In fact, the cast is so generally excellent that many actors, like Kristen Wiig, must count as wasted.

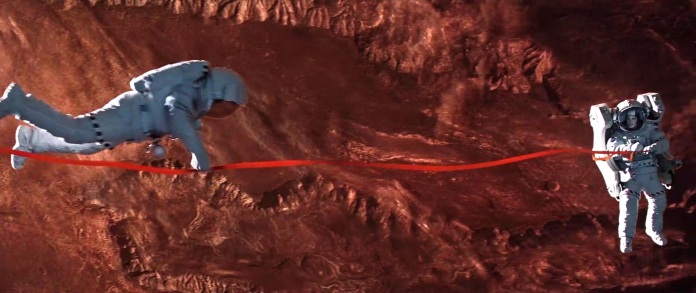

The Martian isn’t perfect. I could’ve done with a few less rounds of NASA technicians cheering and cutaways to enthralled audiences in Times Square and other international locations. The theme of contact and cross-pollination between cultures is one close to Scott’s heart, and yet The Martian gets oddly stiff when contemplating an American’s butt being saved with Chinese aid. Yet something of the crowd-sourced joie de vivre of the novel’s genesis has slipped through into this film, one that invites the audience along and doesn’t talk down much as it explains the minutiae of growing crops on Mars and explores the method Watney has to use to strip down and repurpose the ascent vehicle in order to reach the Hermes, reducing to a “convertible,” as Watney quips, assaulting the craft to the point where it seems unsafe, and indeed this turns out to be so.

The climax is a particularly brilliant display of technique and visual power, ratcheting up tension but also finding weird epiphanies of motion that extend the film’s theme of seeing the beauty and wonder even at the outermost fringes of survival. The jokey yet fundamental theme of music as a basic human need resolves in a zero-gravity dance where the need to grip onto another human is quite literally a life-saving act of faith. Scott and Goddard go further than Weir for a postscript that underlines, amidst a mood of bouncy triumph, the notion that experience equals knowledge that then must be passed on in the same way a seed leads to a green shoot. Such uncynical epiphanies make The Martian one of the most charming big-budget movies of the year and one of Scott’s most entertaining works.

I really hope “can-do poptimism” wasn’t a typo – that’s a great phrase for the human impulse to succeed, communicated within the necessities of such a large popular medium.

Yours is the only review/commentary of the movie I’ve read, and likely will be the only one (not uncommon). You cover everything I loved about it. For me, the movie is the grand corrective for Gravity – that thin disappointment – while also absorbing and reconstituting the spirit of favorites like Silent Running, Cast Away, Andromeda Strain (as you mentioned), Lord of the Flies, and Lost in Space. And lest I forget, much of the buoyancy of the movie is provided by that which its lead character makes the most fun of: that disco soundtrack – perhaps lifting from Guardians of the Galaxy the only thing worth lifting from it.

This was a very enjoyable movie.

LikeLike

I think I left that last thought incomplete – I meant to say that the music pumping through GotG was, upon hindsight, the only thing I actually really enjoyed about it. This movie uses the SOUND/FUN of old songs to somehow tamp down the potential dullness of matter-of-fact science (not that it really needed to), much like GotG used it as replacement for character (which it definitely needed to).

LikeLike

Also, got curious and looked back at your Gravity piece. This quote from you in our back and forth in the comments couldn’t help but leap up at me: “I would however say that if Cuaron’s efforts do have a knock-on effect and inspire more of what I suppose could be called “realist blockbusters” then I’d consider it a worthwhile exercise.” Maybe The Martian is the knock-on effect that redeems Gravity after all?

LikeLike

Rob;

Yes, I meant to write poptimism. It’s a word I wouldn’t normally use (and it’s usually used as a pejorative) and yet it felt really apt here. I wouldn’t say the soundtrack idea was pinched from Guardians of the Galaxy though – the idea was fully present in the book, although GOTG’s success might have helped grease the wheels a bit in selling the film to execs. Scott does a good job avoiding making the apposition of the music and the drama silly; instead it just feels wry. And at least the music heard here is disco; Weir in the book has Watney describing Bowie’s “Life on Mars” as disco, which made me wonder if he actually knew what it is other than an easy humour source. For Weir it was punchline; for Scott, a funny but charming form of surrealness, even an incantation for life. Both instances seem to me like callbacks to the likes of Dark Star and Red Dwarf, works based around a vaguely punkish disconnection between the usually pompous genre business and the notion of slackers and recalicitrants called upon to do that business.

I’d totally forgotten about that comment back in the grand old days of our Gravity bashing, but I’d say there is some truth in that. But I also think there’s an odd influence of Breaking Bad here as well – the SCIENCE! badassery of that series put to work in a different genre. And I even think there’s some odd connection with a recent run of man-vs-wild movies like The Grey, Into the Grizzly Maze, Backcountry etc — a desire in filmmakers and audiences to see characters thrust far out of comfort zones and giving it their best.

Either way, this film’s a class act in what’s been a profoundly flat year of cinema.

LikeLike

Influence of Breaking Bad, definitely, but having worked on CSI:Miami (don’t laugh!), I’d say that franchise as well – some of the movie’s sciencey interludes had me kneejerk-hoping the screen didn’t split into 4 or 5 unfollowable boxes of activity. How I hated that device on the show. Yes, the film’s classiness disallowed such vulgarities.

LikeLike

LOL – I’d forgotten that was a show you’d worked on. Funny, Marilyn saw the CSI connection too. It never occurred to me.

LikeLike