.

Director/Coscreenwriter: George Lucas

By Roderick Heath

The fervent anticipation at the nearing release of Star Wars – Episode VII: The Force Awakens carries an unavoidable sensation of déjà vu. Like just about everyone else my age, I grew up watching the original Star Wars trilogy, and recall another wave of both powerful hype and real expectation through the closing months of the last millennium that crested with the release of George Lucas’ return to the series, Star Wars – Episode I: The Phantom Menace. This cinematic phenomenon began as a good-humoured, referential piece of space disco created by Lucas, a man who up until 1977 had been best known for a film about teens driving about all night to the musical accompaniment of ’50s oldies. But the series he inaugurated with Star Wars – Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) quickly became something rare: giant blockbusters viewers adopted with the fierce personal attachment of cult films. Stripped down to constituent parts, the original Star Wars films seem simple, even infantile, and yet there’s something incredibly powerful encoded in them, defying reduction if not dissection. Almost inimitable amongst modern special-effects-driven movies, they maintain the rarefied quality of fable, combining cheeky but essentially straitlaced heroism with a quality, in their evocations of places seen and visited, their alien cities dancing on clouds and death machines the size of moons and taverns littered with denizens of two dozen species, that resembles the apparatus of dreaming.

Concurrent with the fond eagerness was a quieter but powerful swell of cynicism from people who disliked the films or resented the hype. Star Wars had germinated as personal fantasia but became marketing event. Lucas began his career with the semi-experimental scifi feature THX 1138 (1971), but more than any other filmmaker of his generation—the so-called Movie Brats—Lucas came to exemplify faith in the broad audience’s wont as well as the artisan-artist’s individual vision. Lucas learnt the hard way about the pitfalls as well as the prospects in making movies for that audience by dealing with the uproar over the nightmarish Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and the flop of the oddball Howard the Duck (1986), and had resolved to be a responsible provider of family entertainment. Facing a new trilogy with much darker and less commercial subject matter than his first series, Lucas at first courted a new generation of young viewers as fans, but he left many feeling he conceded to those young folk excessively. The people who already loved Star Wars certainly weren’t kids anymore. They were 20- and 30-somethings who wanted, whether they knew it or not, two completely divergent yet equally necessary sensations: the feeling of being thrust back to childhood even whilst simultaneously acknowledging their evolution. The Matrix, released a few months before The Phantom Menace, became the film the latter singularly refused to be, a superman fantasy dressed up in pseudo-grit and cyberpunk quotes that fitted the mood of the time. The Phantom Menace was a huge hit, but soon became a byword for the cultural equivalent of a fumbled touchdown. That said, I was and still am bewildered by the level of invective the prequel trilogy receives. In some ways, I even prefer those films today.

I don’t say this just for the sake of contrariness. Some criticism levelled at the trilogy is legitimate and feelings of dashed expectations are honest enough for many. But I also feel this cult of disdain exemplified something notably obnoxious about the dawning age of the internet, a deeply spoiled capacity to judge with distinction or consider with a sense of history that refers outside of the bubble of fandom, or the opposite, charmless snootiness turned on popular cinema. I think of how lumbering and over-hyped a lot of modern franchises have proven over a stretch of ground—The Dark Knight, Pirates of the Caribbean, Transformers and Twilight and The Hunger Games series, even to a certain extent the Marvel superhero films. So many are testimonies to a brand of professional smoothness or an anodyne brand of fun, rarely taking any risks or offering real ambition to match their flimsy gravitas. Peter Jackson’s Tolkien adaptations, formidable as they are, rendered the epic and the fantastic in a manner that remains resolutely concrete, sapped of relevance as parable, and the more they try for the ethereal, the less they seem. So I’ve found myself returning often to the colour and expansive glee apparent in even the least of the Star Wars movies. There’s real beauty and great invention to be found in the prequel trilogy. At their best, they exemplify the creed of the project as it began to explore complicated ideas and motifs through apparently cheery and unpretentious figurations. Lucas had originally drawn on nearly a century’s worth of space opera scifi and pulp storytelling as well as more serious sources.

The surprising thing about The Phantom Menace is how well Lucas captures the tone of some of the stuff he alludes to—the broad, tony, featherweight joie de vivre of a Saturday afternoon adventure film by someone like Nathan Juran or Richard Thorpe. People wanted the Star Wars prequels to be about their childhoods, but the series remained, in utterly crucial ways, an account of Lucas’ youth. One definite impact upon my own sense of art and artistry I can say the series had was the way it introduced me to the idea of auteurist cinema. George Lucas was Star Wars; even when he wasn’t directing, his influence was still all over the product. This eventually proved a sword with two edges, as Lucas the creator became the boogeyman of fanboy campfire tales.

The overarching story of the prequel trilogy is straightforward, but also much more complex in its dimensions and ramifications than the original trilogy’s. The trilogy depicts the transformation of the Galactic Republic, an ancient, galaxy-spanning alliance of planets, into a fascistic Empire. Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid), a devotee of the once hugely powerful but long since toppled mystic society called the Sith, is at first a mere senator from the planet of Naboo. He engineers a plot in multiple stages, first leveraging himself into the chancellorship of the Republic Senate by creating a crisis between his home world and a cabal of smug, fish-faced aliens called the Trade Federation, led by Nute Gunray (Silas Carson). Palpatine then foments a full-scale civil war between Republic loyalists and disaffected groups, using his adherent and accomplice Count Dooku (Christopher Lee) to manipulate events until he is given dictatorial powers, permitting him to create a full-scale army of clones to control his domain. Then Palpatine moves to wipe out the Jedi, the Republic peacekeepers who adhere to an antipathetic philosophy to the Sith whilst drawing on the same quasi-spiritual energy source known as the Force.

Woven into the fabric of his plot are three core characters: the elected Queen and later Senator of Naboo, Padmé Amidala (Natalie Portman), Jedi knight Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor), and his pupil Anakin Skywalker (played as a kid by Jake Lloyd, as a man by Hayden Christensen). The Phantom Menace tells how Obi-Wan and mentor Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) save Padmé and aid her in reconquering Naboo from the Federation. They encounter young Anakin by chance when hiding out on the remote, barbaric desert planet Tatooine, where he and his mother Shmi (Pernilla August) are slaves to gruff, sleazy trader Watto (Andrew Secombe). Anakin’s uniquely powerful ways with the Force help gain a victory, and after Qui-Gon’s death in battle with Palpatine’s initial apprentice Darth Maul (Ray Park), Obi-Wan convinces the Jedi Council to let him train the winning, but possibly unstable young prodigy. Whilst The Phantom Menace is the least effective of the six feature films to date in the series, it also clearly illustrates the uncool side of Lucas’ obsessions in a way that also confirms their meaning to him. In its first 40 minutes or so, the episode has a much more juvenile style and tone than the other films and is the one most clearly made with a young audience in mind. As much as this tone acts like nails on a chalkboard for older viewers, it’s not actually a flaw in itself.

That said, Lucas had not personally directed a whole film in 22 years, and the one-time savant of ’70s cinema had clearly grown stiff in the joints. Some parts of this revival are brilliantly executed, others weakly patched together. Early special-effects sequences in the episode are awkward and feel unfinished—particularly an underwater journey for the Jedi—and replete with edits that come a beat too late. The much-hyped, first-ever, completely computer-generated character in a feature film proved to be Jar Jar Binks (voiced by Ahmed Best), a floppy-eared, lizard-like alien from a Naboo race called the Gungans who seems composed of a few hundred different comic-relief figures (and ethnic clichés) from old movies. I generally side with popular opinion here: Jar Jar is an annoying figure who nudges the material too close to the cartoonish, lacking the fierce-cute appeal of the often derided but lovable Ewoks. That said, although Jar Jar grates badly in early scenes, his involvement in a climactic battle through which he careens like Jerry Lewis trying to be Errol Flynn, bringing terror and destruction to both the enemy and his own fellow Gungans, blends comedy and action well in a sequence that calls out directly to a lot of classic swashbucklers, like Nick Cravat darting through danger in The Crimson Pirate (1953) or Herbert Mundin amidst the throng at the end of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

An extended subplot involving the substitution of the real Padmé, who pretends to be one of her own handmaidens behind a decoy, played by a very young Keira Knightley, means Portman and Knightley are forced into awkwardly imitating each other with a weird mid-Atlantic accent. But Padmé begins her evolution into perhaps the most interesting character in the franchise. She’s a product of a culture with a curious predilection for being governed by emotionally and intellectually advanced young women, one who remains the voice of social and political wisdom in the trilogy and a gutsy fighter who has a tendency to leap into frays where others hesitate but who founders on her love for a younger, volatile man. The Ruritanian look of Naboo has a fervent and colourful charm, again clearly linking the instalment with the fantasy filmmaking of Lucas’ youth like Knights of the Round Table (1954) or Jack the Giant Killer (1962). The core theme of the story is distrustful races coming together to fight a common enemy, as the humans of Naboo ally with Jar Jar’s people, the Gungans. The last word spoken in the film is the Gungan king’s (Brian Blessed) cry of “Peace!”, contextualising the trilogy’s developing story as a decline from a state of civilisation into a time of turmoil, ruction, and bloodshed. War comes not as great and appealing crusade or assaults by conveniently abstract others, but because of the manipulations of cabals hoping to gain power or money. Images throughout the film of the Federation’s war machines trammelling the lush, green beauty of Naboo introduce a recurring note of concern for the environment, nodding toward the same themes of natural purity and the insatiable ravening of sentience depicted in Wagner’s Das Rheingold.

The core sequence, again often criticised but actually a terrific bit of filmmaking, comes when Qui-Gon manipulates events on Tatooine to allow him and his party to escape with young Anakin, which requires letting Anakin enter a dangerous form of competition known as the Pod Race. This sequence provides another evident reference to a movie that stands as distinct precursor to the Star Wars series in both production grandeur and self-mythologising style, William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959). Whereas the chariot race in that film was a climax, here the pod race actually inaugurates the essential Star Wars myth. It is the spectacle of something new and amazing coming into the world, and serves at least four purposes in dramatic context. In straight narrative terms, it solves the crisis of how the heroes will get off Tatooine and leads to Anakin joining their team. It’s also an action set-piece that jolts the spluttering film to life. It focuses not just the story, but also the mythic element in the evolving epic tale as Anakin’s great, courageous, already faintly berserk talent reveals itself for the first time. It also revives the panoramic aspect that’s always been crucial to Star Wars, as tiny, enriching details flit by, from a bored Jabba the Hut overseeing the race and flicking bugs off his booth’s ledge to vendors selling alien small fry to hungry viewers whilst the two-headed race caller mouths off with sarcastic glee. This sort of stuff is, to me, always a great part of the pleasure of Lucas’ creation, a universe of recognisable things given a fantastic, slightly mocking but ultimately effusive makeover. Also, given how junky a lot of ’90s action filmmaking looks today, this sequence is especially great in its clean and fluid use of widescreen, and the perfect legibility of the visual grammar. But sequences like this sit cheek by jowl with awkward ones, like Anakin being teased by some fellow Tatooine waifs, where the style of acting and humour strays too far into a broad and juvenile place, like a Saturday morning children’s show.

Climactic scenes of The Phantom Menace may push the kiddie wish-fulfilment a bit far as Anakin saves the day by blowing up a Trade Federation control ship to a chorus of applause. But the lightsaber duel between the Jedi and Darth Maul, which costs Qui-Gon’s life and reveals Obi-Wan’s gift for surprising pompous opponents, is in the best series tradition, and indeed perhaps can be said to re-found that tradition. Attack of the Clones, the first follow-up, is probably the most frustrating entry in the entire cycle. The episode encompasses some heavy lifting in the overall narrative, depicting Anakin simultaneously as a brave and gallant knight who wields an almost unnerving romantic fixity in pursuing Padmé, but also harbouring a dangerously fraying psyche. This side to him, though sensed warily by the leading Jedi Yoda (Frank Oz) and Mace Windu (Samuel L. Jackson), is revealed when he returns to Tatooine looking for his mother Shmi (Pernilla August), only to find her on the edge of death after being kidnapped and tortured by humanoid nomads known as Sandpeople. Anakin, stirred to psychotic rage after Shmi expires in his arms, slaughters a whole village of them. The monster within Anakin is hatching, byproduct of both his alienated and exploited youth and the process of becoming a Jedi, a process that was supposed to ennoble and cleanse him of such evil. Anakin confesses his act to Padmé, alternating shows of rage, adolescent petulance, grief, and bewildered self-reprehension. Padmé, resisting her own ardour for the handsome warrior, nonetheless acquiesces to and covers up his lunacy.

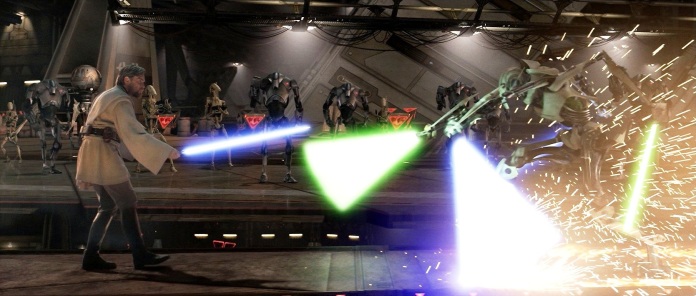

Parts of Attack of the Clones have a romantic grandeur that easily match the best moments in any other episodes and strike at the heart of the appeal of this universe. The film starts effectively with a noirish sequence depicting an assassination attempt on Padmé that kills one of her doubles, a moment that signals immediately that the kiddie games of The Phantom Menace are over. Anakin and Padmé kissing before being wheeled out for a death match before a stadium full of insect men is a moment carved out of the very ore of the fantasy epic. The climactic battle sequences, including a tribute to Ray Harryhausen as our heroes battle a trio of monsters, the Jedi finally depicted at their best as they rally to save our heroes and fight off an army of robots, and Yoda and Dooku meeting in a lightsaber duel, are great entertainment, gathering a rolling, rollicking intensity. The landscapes on display are a diorama of fetish points for space opera and classic scifi—robots, aliens, Art Deco supercities, technogothic castles, glistening chrome space ships, and stygian automated factories, as if decades of Amazing Stories and Astounding magazine covers have come to life. Mixed in with this are references to the ’50s pop culture beloved of Lucas, like diners and hot-rod-like speeders and spacecraft, making for the deepest immersion in the fantasy world Lucas had created.

But the episode is also beset by a baggy narrative that wastes screen time when it should be developing the tortured romance of Anakin and Padmé, whose affair unfolds in settings straight out of Pre-Raphaelite art. Instead we’re lumped with a couple of action scenes that come across more as show reels for the increasingly good digital effects or blueprints for computer games, like an asteroid field chase and a sequence in a droid assembly plant that is well-done and has a certain thematic force by portraying our heroes trying not to be more literally stamped out by a heedlessly working machine, but could easily have been left out. Some sequences even stir thrills and a touch of exasperation at the same time, like the early chase sequence through the planetwide city of Coruscant. Wisely, Lucas reduced Jar Jar to a handful of cameos here, as a malleable political stand-in for Padmé, whilst the reliable duo of C3-P0 (Anthony Daniels) and R2-D2 (Kenny Baker) are turned to for comic relief, though the pair don’t wield the importance or sharpness of humour they had in the original trilogy. For all its flaws, though, Attack of the Clones is a vigorous, fun, substantial work. Many of the best moments, odd for such a piece of big filmmaking, tend to be tossed-off asides: Obi-Wan using a Jedi mind trick on a barroom drug dealer, Anakin playing Joe Friday with bar patrons, bounty hunter Jango Fett (Temuera Morrison) spinning his blaster like a gunslinger after shooting down a Jedi, C3-P0 having a killer droid head welded onto his body, and the sight of Anakin speeding across the Tattooine landscape on a futuristic motorcycle like the Wild One gone Zen Ronin.

A great part of the appeal of the original series lay in the relatively broad simplicity of its heroes, who stood for clear, easily graspable, positive values. Even Han Solo, the slightly tarnished wiseguy uneasily elevated to crusader status, is hardly a Dostoyevsky character. The characters did evolve, but only Luke really deepened, and his journey from fresh-faced farm boy, an obvious avatar for the audience’s fantastic yearnings, to grim inheritor of cosmic destiny, bore most of the real dramatic and mythic weight. By comparison, the prequels force one to empathise with a callow budding psychopath, his enabling lover, and his emotionally constipated mentor. These three protagonists each aid in causing the destruction of the world they think they’re defending. The prequels depict a world falling apart and tellingly refuse to let the audience off the hook, no matter how distanced or naïf the rendering of that hook: almost everything the audience wants to see is bound up in this decay. The desire to see action is sated, but immediately indicted by Yoda as proof of failure. The romance of Anakin and Padmé slips its bonds, but signals impending doom for both. The daydream sustained in the original trilogy is therefore critiqued and inverted.

Much as older viewers couldn’t relate to Anakin, many kids and teens did. His deeply egotistical and painfully self-castigating sense of having his potential thwarted and his need for control foiled, and Padmé’s optimism waning into an increasingly detached cynicism towards the political process she stands for, depict states of mind all too prolific in our time, ones that contradict common, conflicting expectations loaded upon young people, to be incredible achievers and unswervingly empathetic idealists all at once. “Only a Sith talks in absolutes,” Obi-Wan warns Anakin as he turns to the dark side. At the time, some took this for a tilt at the rhetoric of George W. Bush, as much as it now sounds like a thumbnail sutra explaining the powerful appeal of groups like Islamic State for some—the promise of complete surrender to a simple cause, a pure mode of thought for which any act can be countenanced. In this regard, Lucas clearly had his pulse on something other populist filmmakers have tried to grasp but usually belaboured. What is also clear to me is that Lucas, when he revisited this material, wanted to try to live within in it on a much deeper level than the original films and pay truer heed to the material’s partial roots in the medieval mythos, both Eastern and Western, where lives were lived and death was met according to rather different value systems. The famous title card of every episode declares that this is all “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…,” but this fairytale motif only really feels true with the prequels. The original films are a charmingly bratty revolution fantasy, where the good guys happen to speak like ’70s American teens and the bad guys have English accents. The prequels are a tragic contemplation of the forces that tear societies, and individuals, to pieces. Lucas’ interest in a chillier, headier brand of scifi parable was obvious right from THX 1138 and here found further articulation.

This quality emerges strongly in the last film of the trilogy, Revenge of the Sith, where Palpatine’s attempts to win over Anakin resemble at once a seduction, therapy session, and a chess match of moral relativism. In the original trilogy, evil was, like in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, an elixir that once tasted was totally subsuming. In the prequel trilogy, both the light and the dark sides are more processes of thought and ways of feeling: by the time he becomes Darth Vader, Anakin is convinced he’s bringing peace and justice to the realm. A constant leitmotif to the prequels is a sense of ethical questioning and a tension between the personal and the political that ultimately destroys both the Jedi and Anakin by pulling them in asymmetrical directions. Yoda warns young Anakin about maintaining attachments and giving himself cause for fear, and it’s precisely this that ultimately leads him straight into Palpatine’s arms. But the Jedi, presented as uncomplicated paragons whose aura is legendary in the original series, are here revealed as gallant but also demanding and elitist, almost incomprehensible to someone who runs on emotion as much as Anakin and perhaps ultimately too detached from the fate of the Republic to actually save it in part because of their own ethic of accepting loss.

Lucas shows he understands something vital about courtly sagas and classical tragedy: the requirements of role and the nature of humanity are disparate and demanding things. Lucas literalises the tension key to the prequels between role and person early on with Padmé’s absurd regalia, a crushing weight of stately role that continues to stand like a statue even when she’s entirely outside of it. Jar Jar actually serves a fairly analogous role here as Han Solo did to the original films, if much less successfully, as a character who remains oblivious to the pretences of the civilised and the imposing (“Maxi big the Force!”). His clumsiness is the very opposite to the ideal of disciplined self-abnegation that defines the Jedi and also the fetishism of power and order that defines the Sith.

The writing of the prequels is often criticised, but what this brings up is just exactly what is good writing in such a context? Is it the writing of, say, Joss Whedon, where everyone, no matter where they come from, speaks like a smart-aleck English major in a Californian college, or the brick-heavy koans of Christopher Nolan? That famous quote of Howard Hawks about the trouble working out how a Pharaoh should talk for Land of the Pharaohs (1955) (“I don’t know how a Pharaoh talks. And Faulkner didn’t know. None of us knew.”) is still relevant in this regard. Lucas tries, a bit archly but with some purpose, to recreate the flavour of a certain brand of courtly poeticism in speech through the prequels, with a texture on occasion that strives for the flavour of medieval epics— romantic, stylised, high-flown to the point of sounding like recitative. Lucas himself compared it to a kind of a rhythmic sound effect—a fair description. There’s a much-mocked line in Attack of the Clones when Anakin and Padmé share a romantic interlude by the side of a lake. Padmé remembers days of joy swimming and lying on the sand with an old boyfriend, and Anakin feebly jokes how much he hates sand. It is an uncomfortable moment, but deliberately so: Anakin tries to shrug aside a hint of romantic jealousy with humour, but accidentally reveals a hole in his soul, as he’s actually talking about his childhood on a planet where sandstorms were dangerous and life was hard, a place to which he will soon return. Characterisation, backstory, foreshadowing. Not so bad for a dumb joke about sand.

That’s not to cover up the many dud line readings in the prequels, most of which are perplexing as they could’ve been salvaged with a few hours’ dedicated ADR work. It’s definitely true that Lucas accomplishes his aims better with images than words. An iconic shot in Attack of the Clones depicting Anakin regarding the dawn and trying to calm his raw nerves with Padmé hovering in the wings, and the final shot of the same film where the pair get married in the rays of a setting sun, have a transfixing, totemic beauty. Lucas’ formal gifts are, in fact, often greatly in evidence throughout the series, particularly his interest in wide shots replete with geometries that highlight the formalism that defines this age in his fantastical world and the tension about to bust it to pieces.

I think the style is quite deliberate and suits the tone of the material, and is also modulated with a deliberation many didn’t notice, moving from the pantomime-like tone of the opening episode to high operatic drama in the last. But the emphasis on a tense decorum in this futuristic (albeit past) world leaves Portman and Christensen often seeming far more out of place than their predecessors ever did. Christensen, whose chief claim to fame was playing a troubled young misfit on the TV series Higher Ground before Lucas cast him, is one of the most vexing elements of the triptych. Lucas clearly wanted a James Dean-Marlon Brando quality to Anakin, his generational touchstones for rebellious youth and social disaffection, a touch of the immature as well as the fearsome to his asocial side. If Christensen was irredeemably bad, he could simply be allowed to fade into the texture of the films like human wallpaper. But Christensen delivers on occasion, as in the scene when Anakin tells Padmé about the massacre of the Sandpeople: he grasps the degree to which Anakin is composed of alternating repression and inchoate eruption, nobility and monstrosity.

Plummy old pros like McDiarmid, Jackson, and Oz fit into this landscape better. McGregor acquits himself well enough in the series, an achievement considering he had a difficult job in matching his younger, pithier version of Obi-Wan to Alec Guinness’ quiet and assured characterisation. Although he and Christensen have the athleticism, in some ways Portman strikes me as the natural adventurer of the three young stars, dashing about firing ray guns with delighted eyes; her “I call it aggressive negotiations” quip in Attack of the Clones is pure swashbuckle. Another noteworthy performance comes from August, who does a terrific job securing the drama in the spectacle of a mother bereft of her son; the reunion in Attack of the Clones has an unusual pathos because the dying woman is transfixed by the sight of her grown son.

At its best, the prequel trilogy legitimately inhabits the realm of chivalric romance, stocked with themes and stances found in sagas, particularly in the traits that define Anakin, who’s actually much closer to a great mythic hero like Achilles, Jason, or Siegfried than Luke ever was in the violence and intensity of his driving emotions and character stances—forbidden love, crippling conflict between stoic integrity and hysterical eruption, an inability to settle into required strictures of life in the society he represents. Obi-Wan was originally presented as a mentor figure whose initially uncomplicated call to action for Luke was revealed in subsequent instalments to have more dimensions, but he still remained a figure of sagacious wisdom. McGregor plays him as a dashing, but serious-minded warrior-monk who retains a telling and ultimately calamitous blind spot when it comes to Anakin, his pupil and adopted brother, an emotional substitute for the lost father figure of Qui-Gon. This fantasy world is a kind of Eden from which everyone falls, giving birth to a different time and throwing up rogues like Han and Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams).

Many of Lucas’ reference points for creating his mythos were pretty disreputable, including not just the classy art of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon comics but the vulgarity of their screen serial adaptations. A wealth of other reference points is apparent—the swashbucklers of Michael Curtiz, the conceptual richness of Frank Herbert’s Dune novels and the venturesome absurdity of Edgar Rice Burroughs, the sweep of John Ford’s western mythology and the rigorous formality of Akira Kurosawa’s samurai epics, and Ray Harryhausen’s films, which combined ingenious wonders with the ropy charms of B-movies. On the highest level, Lucas has often seemed an acolyte of Cecil B. DeMille, whose embrace of scale and riotous colour as aesthetic tools matched the themes of world-shaping powers with The Ten Commandments (1956), and of Fritz Lang, who laid the groundwork for much of the style of Lucas’ works with his silent epics The Spiders (1919), Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen (1924), and Metropolis (1926)—fantastical pieces of world-building replete with similarly surreal and cavernous environs, action cliffhangers, and stories often split across multiple episodes. Coruscant turns Metropolis’ soaring modernist architecture into an entire world. There’s more than a hint of Die Nibelungen (both movie and source myth, quite apart from Wagner’s take) in the recurring images of crushing courtly stature and state, infernal downfall and baleful regard. Palpatine sitting at the centre of all plots is the ultimate Mabuse, manipulating the downfall of others for personal amusement, reducing government to a matter of his own will and detecting the weak points of Anakin’s psyche to turn him into a helpless acolyte.

The political substance of the series is a mishmash of historical motifs, blending a parable for the Roman Empire, the Crusades, the American Revolutionary War and Civil War, and World War II, complete with space Nazis and galactic paladins. But the prequels contain a consistent thread of real interest in the idea of what constitutes the self and society, diagnosing cynicism as a problem that’s as pernicious as corruption. The original trilogy only seemed to reference contemporary politics by evoking a generational anxiety of becoming what the ’60s counterculture rebelled against, as Luke tried to avoid becoming his father, whilst the battles of the Ewoks uncomfortably suggested an odd hijacking and inversion of the Vietnam experience. The prequels suggest a more immediate and clarified lesson. “So this is how freedom dies,” Padmé murmurs at one point when the Senate votes to make Palpatine Emperor, “With thunderous applause.” Revenge of the Sith, the concluding movie in the trilogy, has a rueful warning for younger generations of how easy it is to be so subsumed when your leaders manipulate you to commit evil in the name of good, with Anakin, youth and talent personified, seduced by promises of power and privilege, called to commit slaughter in the name of peace, to be delivered from fear and frustration. Anakin’s urge to free himself from fear also detaches him from democracy, making him lean toward authoritarianism, the get-things-done attitude of Palpatine.

One of the most obviously powerful qualities of the series since its inception has always been John Williams’ scoring, and perhaps the most inarguably strong aspect of the prequels is his music, particularly the “Duel of the Fates” piece used in The Phantom Menace, the lush “Across the Stars” motif in Attack of the Clones, and the thunderous drums and choral works resounding throughout Revenge of the Sith. The prequels sport a few nods to the original trilogy that are perhaps excessively cute—having C3-PO prove to have been an engineering project of young Anakin’s, making Boba Fett’s father Jango the genetic source of all the initial wave of clone Imperial Stormtroopers. But there are also some refined and intelligible touches of foreshadowing and mirroring throughout, particularly in Anakin’s two duels with Count Dooku, which mimic cinematic effects and story patterning in The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983) in suggesting the same forces of fate and divergence of character that define fathers and sons, masters and pupils. Revenge of the Sith signals the closing bookend to the trilogy in echoing Episode VI – Return of the Jedi, as Palpatine’s plots reach climax, the Jedi are wiped out, and Anakin begins a precipitous transformation into that darkest of dark marauders, Darth Vader.

Frankly, Revenge of the Sith is the best of the Star Wars films, a grandiose distillation of the entire concept of space opera scifi, the closest the series has come yet to fulfilling its neo-Wagnerian streak. It’s also the tightest, most dynamic piece of filmmaking, a narrative inexorable in the same way as A New Hope, except on a downward trajectory, successfully carrying through a promise to turn into high tragedy. Elements that had problems connecting and synchronising in the first two films snap into gear here— even Christensen is fairly okay—if at the relative expense of some aspects, including Padmé, as the dashing figure she cut in the first two instalments is here reduced to mere weepy baby mama, for the most part. The opening sequence is a marvel that shows how far special effects advanced even in the six years since the trilogy began, and unfolds as a pure episode of swashbuckling action, as Anakin and Obi-Wan try to rescue Palpatine, who’s been kidnapped by Dooku and cyborg rebel leader General Grievous. Anakin defeats Dooku this time and kills him at the chancellor’s behest, and finishes up having to pilot a massive crashing spaceship in for a neat landing. This whole sequence is a piece of cinema spectacle I don’t think anyone’s topped in the last 10 years. Revenge of the Sith alternates the urge to such kinetic release and intense, yet quiet, almost cerebral sequences where the characters grope their way through their contradictory impulses and collapsing worldviews.

Another very large reason I like these films is that they reject nearly every modish trick of so much contemporary filmmaking. As modern, perhaps excessively so, as the digital special effects seemed upon release, the actual cinematic design of the films is rich and classical in utilising the screen’s expanse, and those much-quibbled-over effects, sometimes gorgeous and sometimes cheesy, offer to me a quality like the painted wonders of old matte effects – not realistic, but transportive on some level. There’s scarcely a single too-tightly-framed shot or jerky camera moment in all seven hours of the filmmaking here. Lucas’ trademark Kurosawan screen wipes nudge visual and narrative structure along with fluidic insistence. I’ll also admit I have a liking for aspects of these films from which others recoil. I enjoy Lucas’ happy embrace of the kind of outsized, old-fashioned melodrama and idealization usually filtered out of modern tent-pole films where the cult of awesome has a very narrow range of definition; the scenes of Anakin and Padmé swooning in the fields of Naboo, which have a resplendent, flower-child goofiness to them, and Vader’s final, over-the-top cry of “NO!” are big, gregarious middle fingers turned up at the middling, sometimes nonexistent emotional range of most of Lucas’ inheritors. Revenge of the Sith concludes the move away from the kid-friendly tone of The Phantom Menace, as here the young Jedi are butchered en masse by Anakin amidst a night of long light sabers. Marching ranks of Stormtroopers invade the Jedi temple, and Anakin heads to the planet Mustafar to wipe out the separatist leaders, including Nute Gunray, now that Palpatine no longer needs them.

Lucas’ direction, which grows more vigorous and animated throughout the trilogy, cuts loose in this movement, replete with delirious high viewpoints of marching armies, cross-cut glimpses of myriad alien worlds where other Jedi are betrayed and ambushed, and the churning violence Anakin turns on his enemies, carving up the separatists with a savagery that’s quite unmatched in the whole six-film cycle. The finale of Sith, at once paving the way for the next cycle of history and underlining the total collapse of everything depicted as sacrosanct and worthy in the previous three films, sees Obi-Wan and Anakin battling over Padmé’s crumpled, pregnant form on a volcanic planet where the spuming lava flows mimic the emotional landscape of the characters and the action unfolds in gloriously hyperbolic manner. Molten rock erupts, sparks fly, light sabers streak and slash, colossal machines fall apart and melt. The mimetic quality of Lucas’ creation is at its most unrestrained and beautiful here: I’m not sure if mainstream cinema had seen its like since the days of DeMille, or Powell and Pressburger, whose Black Narcissus (1946) and The Red Shoes (1948) similarly paint obsession and jealousy, love and hate, in bold tones of bloody red and dancelike motion and vertiginous danger.

Lucas does grant concessions to the remnant heroic ideal at the heart of the series. Yoda gives the newly crowned Emperor a bit of what-for before fleeing in the face of the crushing political machine the Sith now wields, and Obi-Wan quite literally cuts Anakin’s legs from under him when the young, increasingly mad tyro overreaches and underestimates his opponent. The concluding scenes take the cross-cutting structure to a striking place as two different kinds of death and birth are contrasted—the waning life-force of Padmé even as she struggles to give birth to the crucial Dioscuri of the next epoch, Luke and Leia, matched with the reconstruction of the mangled and pathetic Anakin into the monstrous form of Darth Vader. There’s a perverse and gruelling quality to these scenes that, again, defined new territory for a series once based in mere boyish adventure. The themes of rebirth, cycles and family, decay and renewal, conclude in images of funeral, as Padme is celebrated in death by Naboo, and homecoming, with Leia finding a home with Senator Organa (Jimmy Smits) and his wife. But the very last shot inevitably returns to that most memorable image of A New Hope, as young Luke is held by his aunt and uncle (Joel Edgerton and Bonnie Maree Piesse) as they gaze out on the twin suns of Tatooine, the future with its horrors and glories a distant promise.

Thanks, Andre.

Rosie, one of my more significant complaints about the original trilogy is that in spite of the richness of the world-building, the stories are so damn simple. Which is, I dare say, part of why they’re so easy to love as kids. But these days watching them as much as I enjoy the imagery and crafting and the interaction of the characters, I do find myself frustrated a little at how slight the actual plots and how limited the scope of the storytelling is, especially since watching the prequels has enriched the conceptual basis for the series far more.

Also, I wrote about Return of the Jedi in the past and noted some of the reasons why I prefer it to The Empire Strikes Back:

https://filmfreedonia.com/2012/09/27/star-wars-episode-vi-return-of-the-jedi-1983/

LikeLike

[“I don’t say this just for the sake of contrariness. Some criticism levelled at the trilogy is legitimate and feelings of dashed expectations are honest enough for many. “]

What kind of criticism would you level at the Original Trilogy? I can think of plenty.

LikeLike

Wonderful review! Congratulations, Rod!

LikeLike

I’ll keep it short, and simply paraphrase a Riddle joke from The Long Halloween.

How is Roderick Heath like a row boat? They both have a bow to take.

LikeLike

Heh! Thanks Bob.

LikeLike

Quick aside– Have you ever checked out “The Clone Wars” series? It does a good job of smoothing out a lot of the rough elements of these films, and builds on what they establish. Plus, more space-opera serial fun.

LikeLike

I haven’t Bob. I’ve heard nothing but good things about it, but frankly I’m too attached to my big, live-action, vitally cinematic Star Wars, if you know what I mean. I have however been thinking about paying it a visit.

LikeLike

I happen to think that Christensen does a far better job than he’s largely credited with, of pulling off a sort of adventure serial James Dean, in a kind of thirties externalised performance style, replete with stilted James Earl Jones inflection to sell the character’s ultimate trajectory, heightened by Lucas’s more formal, if still cartoonish prequel dialogue. I get why it might grate, but it always worked for me.

The juvenile qualities of The Phantom Menace too, seem less to me about courting youngsters (though Lucas certainly is) and more about creating a vibe of naive innocence ripe for exploitation by malevolent forces, which infects Anakin Skywalker’s story, by way of his guileless or haphazard victories, with a kind of arrested development which lays the groundwork for his eventual fall through hubris, self-entitlement, and power lust.

Also, I could never manage to be bothered by Jar Jar Binks.

With all that said, I agree with far (far) more here than I don’t. This is a fantastic piece sir, and a very enjoyable read. Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

One of the best critiques of the prequels I’ve read. Bravo.

I also never minded Jar Jar (just wished he was left out off Tatooine since there was no reason for him to be there).

There’re some editing issues, primarily in AOTC, which is rather strange since Lucas always said it was his favorite part of the process.

I do agree with Tony than Christensen is more solid than seems at first. He nails some key scenes (especially Confession) and doesn’t get enough credit for imitating Prowse’s body language.

I think you have a good point about young people relating to Anakin’s alienation. I’m only slightly older than Hayden (and not a guy) but I found him relatable to some extent. I’m always baffled whenever someone declares Anakin totally unlikable or unrelatable or just a psycho. It’s like they forgot what it’s like to be a teenager. Anakin feels powerless but at the same time has a lot of power in his hands. That’s an explosive combination and I think it’s explored very well in the movies that, for all intents and purposes, are big budget version of Flash Gordon.

LikeLike

This is a wonderful and insightful piece, Roderick, thanks much for sharing it. You’ve really encapsulated much of my own thoughts and feelings on the prequel trilogy and even while I’ve preferred revisiting it’s installments more than the original trilogy during the last 10 years. And yes, The Clone Wars TV series is also worth checking out!

LikeLike

Excellent analysis, Roderick, and kudos for examining generational conflicts that have influenced criticism of the Star Wars prequels.

I disagree with your assessment with Phantom Menace as the weakest film; it not the best, but I think it’s status as “the kiddie one” required Lucas to utilize a lot of clever subtext and subversion in the visuals (and while it has more flaws than A New Hope, it’s a much more interesting film). Attack of the Clones is the only one I have big problems with, mainly because of the throbbing obviousness of the rushed conspiracy subplot regarding the Clones, but to be fair it is saved by the romanticism and the thrilling climax.

Totally agree that Revenge of the Sith is the best Star Wars to date. It had a huge influence on my approach to film analysis since I first saw, and it provoked me to revisit Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi.

One thing I’ve always virulently disagreed with Lucas on concerns the Original Trilogy Special Editions, because they reduce the thematic impact of the prequels. The contrast between the cold pale Space Age chrome-tone of the OT and the vibrant fiery technicolor impressionism of the PT is lost when the OT is saddled with out of place CGI…

LikeLike

This is fantastic, Rod. For the hour or so it took to read and absorb, you redeemed those 7 screen hours. I haven’t seen the movies since the theater – mainly out of my memory of thudding boredom mixed with utter bemusement. BUT… with this essay as my guide, I look forward to climbing back into the world again. I think I’ve learned a lot in the interim about reading a movie as an organic thing that has its own rules that often (or mostly) live outside my expectations and assumptions – meaning, don’t question so much while watching, just live in what’s there. I think your essays over the years have been integral to that evolution, as you’ve time and time again observed nuance and value in that which has been maligned or forgotten. I’ve no doubt I’ll like these more the second go round thanks to your incredibly detailed, lovingly posited essay.

LikeLike

Hi, guys. Thanks for commenting.

Tony, I actually agree with you quite a bit, if in a mixed way. I criticised Christensen pointedly here but I think there’s a lot of truth to what you say about him. I think therein lies part of why I feel his performance is awkward: combining the externalised style with Method touches is difficult – Brando could do it, but he was Brando – and Christensen doesn’t entirely pull it off, swaying uneasily between styles. One admirable thing he does bring to the part is a deeper level of seriousness then one expects: he never winks at the audience and says, this is all a game. He definitely is better than many have given him credit for (and actually his Bob Dylan in Factory Girl wasn’t that shabby either). I similarly feel that juvenalia of The Phantom Menace is in part deliberate as you say – the trilogy does the same trick as the Harry Potter tales did in growing up stylistically as well as chronologically. I appreciate the way it prizes and maintains that innocent, old-fashioned quality I spoke of above, whilst quietly clearing ground for moving beyond that. But I also think this partly to leverage selling them to kids. Hell, I remember interviews with Lucas before TPM came out, and he was quite open about it being aimed at kids.

Natalie, thanks for bringing a personal commentary on your attitude to Anakin there. You and Tony both have brought attention to the way Christensen paid heed to the physical and vocal styles of the actors associated with Darth Vader. I’d never really noticed (not in the same way I noticed McGregor doing to the same thing with Guinness) but in thinking about it I can see what you mean. I think a lot of folks expected a Vader who acts like Vader except with the mask off (I confess to wishing originally that a more identifiably saturnine actor had been cast in the role, but I also saw what Lucas was after in Christensen). But Christensen never really does that, however. His Anakin dances where Vader prowls and barges his way through situations, a by-product of his biomechanic stature and complete emptiness as a being by that stage. Vader isn’t entirely created until the process of rebuilding him is completed, which highlights the idea introduced in the original trilogy that Vader and Anakin were to a certain extent two different personas.

Brian, I see with yours and Bob’s lobbying I’m going to have to devote a few hours of the near future to watching The Clone Wars.

Jason, Obviously we have relative disagreements over the relative values of The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones. I will say that my feelings for AOTC have actually cooled a bit since I first saw it – I found it splendiferous as an audio-visual experience and very lightweight; now I recognise there’s actually quite a bit of substance to it but that this makes some of the “fun” feel a bit distracting. But I’m still often surprised when people say it’s the worst Star Wars film. As for TPM, sometimes I get in synch with its specific program, and I enjoy it smoothly, and other times it bugs the hell out of me. On the most recent viewing, the bugs were at the fore. But there’re still a lot of qualities to it, and I’ve tried to get at why I have issues with it whilst also trying to hack away the hyperbole that’s grown about it. But I do agree with you about the problematic nature of the touched-up originals, both for the reasons you state and also because simply those digital effects are rather poor and sit very gauchely amongst the visual textures of the originals.

Robert, if you don’t mind me throwing a bit of a film school assignment at you, watch these films after sitting down and watching a few of the older films I’ve mentioned. I remember when I was a kid, watching The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and thinking, when the heroes swing over a pit filled with lava, “They stole that from Star Wars!” But of course, it’s the other way around…

LikeLike

I don’t mind assignments! And there are a few that I’ll need to see (Crimson Pirate, Knights of the Round Table, Lang’s silent films) – the rest I’m pretty sure I saw after the second trilogy came out, so I had it backwards (as you did with SW and 7th Voyage). For me, in cases like this, it always takes someone connecting the dots for me – left to my own devices, the automatic recoil from the wall-to-wall CGI makes that all I can see. By now I’m used to the feeling this level of CGI gives me (essentially, I’ve accepted that big CGI movies will go down smoother if I treat them more as ambitious cartoons), so now I’ll be able to see more of the forest despite the trees.

LikeLike

Actually I might lead you astray there – Knights of the Round Table, although as I said a legitimate precursor, isn’t very good as I recall. I’d recommend the other two Thorpe/Taylor medieval collabs, Ivanhoe and Quentin Durward. But yeah, you really have to see Lang’s silents if you haven’t already. Die Nibelungen is quickly scaling the ranks of my very favourite films.

LikeLike

Die Nibelungen is fantastic. Maybe Lang’s best work in its complete form (I love Metropolis and the Mabuse films, but there’s stuff missing from both, especially a true score for the latter). Lang really is an essential key to understanding Lucas and what he’s doing with the form. One wonders how much Lucas knew about the original version of Metropolis and the cut subplots that were restored throughout the 00s, because between the whole Hel love triangle and how it informs Rotwang and the robot (that glove!) it all screams Prequel.

LikeLike

I’d say that’s entirely a possibility, Bob. Maybe Lucas also read Thea von Harbou’s source novel too and was influenced by that. But also, I expect it’s the patterns of mythology Lucas and Land and Von Harbou are drawn to – such similar plot movements and patterns in Die Nibelungen amplified and rearranged in Metropolis and again in The Tiger of Eschnapur/The Indian Tomb.

LikeLike

Great stuff, Rod! This is a towering achievement and a helluva read. I will admit to being a big fan of the Original Trilogy and was very disappointed by the prequels but your eloquent examination of them has got me thinking that perhaps it is time to revisit them with some of your points in mind.

LikeLike

Terrific stuff. Much appreciated. I remember feeling at the time (haven’t revisited these) that there was a second, probably inappropriate movie trying to bust out of AotC – a sad, Chandleresque or maybe even Ross MacDonaldeque noir story of a detective (Kenobi) investigating a crime so vast he can’t even really sense it even as he stands in the middle of it – the murder of his civilization.

LikeLike

J.D.: Thanks, man. If I can help just one person – sniff! – appreciate these films a bit more than my work was worth it.

Darrell: That’s great. I do actually want to see that movie, although I guess it wouldn’t be Star Wars, but Blade Runner. I do actually think that some of the lack of balance in AotC actually comes from a little too much attempting to make fans happy in a way that doesn’t fit with the overall narrative intent.

LikeLike

What an interesting read. Thanks very much. I actually think the SW prequels are closer to the original trilogy in some aspects of spirit than the bloated LOTR films were to their source. Instead of arguing along those lines, I’ll say that a few tweaks would have made them vastly better- I can’t abide the seemingly obvious racial caricatures in the first film- they could be considered homage to Flash Gordon and the like but they strongly affect my viewing. This could have been easily fixed.

I also wonder if a slightly older child than Jake Lloyd could have conveyed the seeds of Hayden Christensen’s portrayal better. A smoother transition between the two really would have allowed more development for HC to build on. He sort of plays it with inevitability because that’s what everyone expects I guess, because it is a done deal, but his path to the dark side could have used more narrative oomph or resources established in the first film. I also think the relationship with Padme could have gotten more support if the Anakin of PM were slightly older. I think with almost the same plot, revised stereotypes, and a non JL Anakin, the following films are on much deeper narrative footing.

I think of another special effects spectacle of a kids film, that could easily have dealt with joy and passion of a daredevil kid, but also deeper family and character issues (for example to be dealt with at a later date)- Speed Racer. I think of the pod race and instead of a mugging JL, I wonder if someone older but not yet HC (he would have been very tall for a 12-14 year old)….I hate this game of what if, but sometimes considering the solutions to what is wrong with a film allows one to recognize just what about its bones actually worked- especially if you don’t find a need for too radical of a fix.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this read. Nice to see a defence of the films. They obviously have problems. Though a few of those problems are shared across all 6 films. The amalgam of racial stereotypes and aspects of ‘othered’ cultures that form quite a few characters stand out as particularly irritating for me.

What I find really compelling about the prequels though, that you touch on at points and I’d like to take a moment to explore a litte, is the total failure of the Jedi. Not only are they spectacularly outmanoeuvred by Palpatine but they allow him to corrupt them.

By the end of Attack of the Clones the Jedi are generals in command of an army of slaves and not one of them questions the ethics of this. They question whether an army is wise, whether it may escalate the conflict, but they have no real qualms over the idea of breeding an army of compliant soldiers with not right to decide not to fight (besides suspicion at its fortuitous timing).

When Anakin says in the final film something like “from my point of view the Jedi are evil” who can blame him? This isn’t a statement of moral relativism, it is a statement of justified confusion. A reasonable failure to see any difference between the Jedi and the Sith except that the Jedi are failing and the Sith are rising.

It is a feeling compounded by Obi-Wan’s “only the Sith talk in absolutes” because the statement is so fundamentally untrue. The Jedi have loads of absolutes. The statement is thus not a rejection of moral relativism but simply sophistry. By this point the difference between Jedi and Sith has been reduced to Obi-Wan’s rhetorical sleight-of-hand.

The framing of the shots where the Jedi are ambushed seems rather clever in this light. The audience sees Order 66 from the Jedi perspective: sudden, confusing, no explanation or build up. The move against the Jedi is not actually sudden at all, it is just that the Jedi are blind to almost everything that has been going on.

Another testament to this blindness is their attempt to arrest Palpatine. How far behind the move against them did they have to be to try that? Furthermore how arrogant do they have to have become to be so uncautious in the attempted arrest of a Sith Lord who had eluded them for an unknown but certainly long period of time?

They are so detached from the Republic they fail to notice that Palpatine hasn’t broken the law. He is a monster but he is no revolutionary, everything was done with the permission of the Senate.

The message of the prequels as a whole, for me, is not just that your leaders can manipulate you into doing evil in the name of good but that your enemies can do so too. That one has to be careful not to abandon the light in the name of fighting the dark.

LikeLike

Regarding making movies for children – if you read George’s interviews all the way back to 1977, he’s always been saying that kids under 12 are his primary audience. In that way, he hasn’t changed. This is from his 1999 interview:

“You’ve often said that Star Wars movies are primarily meant for children, but The Phantom Menace was always going to be a film that was going to be significant for twenty/thirtysomethings. How did you address this problem?

Basically I didn’t. I kept it as it was originally intended. You can’t play too much to the marketplace. It’s the same thing with the fans. The fans’ expectations had gotten way high and they wanted a film that was going to change their lives and be the Second Coming. You know, I can’t do that, it’s just a movie. And I can’t say, now I gotta market it to a whole different audience. I tell the story. I knew if I’d made Anakin 15 instead of nine, then it would have been more marketable. If I’d made the Queen 18 instead of 14, then it would have been more marketable. But that isn’t the story. It is important that he be young, that he be at an age where leaving his mother is more of a drama than it would have been at 15. So you just have to do what’s right for the movie, not what’s right for the market.”

http://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/star-wars-archive-george-lucas-1999-interview/

I’m sure he still had some commercial considerations with selling toys and what not. But this is an interesting contrast with Disney who seems to only care about “fans” – mostly, it seems a narrow category disgruntled by the SEs and the prequels.

LikeLike

A brief note to anyone who’s reading this piece having followed the link from The New Statesman or The Telegraph pieces: I was not a kid when prequels came out. I was 20 at the time of the release of The Phantom Menace.

LikeLike

Fantastic write-up. I’ve always loved the prequels, but I’m not a cinephile to the extent that you and most of the other commenters here seem to be, so I’ve always struggled to articulate just why I dig these films so much. I really appreciate your points that these films are thematically deeper than the original trilogy, which flies in the face of the popular consensus that they are actually more juvenile. I rewatch the originals for the masterfully crafted action scenes, but I feel like a had a pretty complete grasp of those films by the time I was 15. The prequels have so many layers of themes and ideas that I’m always discovering something new.

LikeLike

Something else occurred to me: sooner or later more people will realize that we live in a global fascist dictatorship of oligarchy and invasive national and unelected governments and Lucas will be considered a prophet no one listened to.

LikeLike

This is by far a foremost article on the prequels! And a defense at that! I’m glad to see it, especially in light of this new film (whatever ones views on it). I too, have to agree with some of the commentators here, that Christensen does a better job than he’s often given credit for. I think his ability to encapsulate both the youthful energy of Lloyd with the near archaically formal nature of Vader is phenomenal. He’s been handed a difficult job, trying to bridge the gap for the views. His intonations match James Earls Jones’ original work, and also pay homage to Pernilla August’s Swedish accent and speech patterns. In terms of movement, it’s most evident in RotS. While I agree with most everything you’ve written here, I agree with nothing so much as your assessment of RotS as by far the best Star Wars film of the saga. Part of why the prequels are so heavily criticized is simply because the viewership didn’t, and still doesn’t want to have to think about the political and social commentary/implications. The Originals are indeed simple, and always enjoyable, which of course, is why so many people disliked the prequels on principle. It’s a ridiculous and lazy notion to be sure, but understandable, considering what they’d come to expect. It’s rather elitist, to say the least, and I think there’s something to be said for its implications within the plot of the story and the statement the prequels in particular seem to make. People don’t want to have to think about it. It’s too dark, and far too deep in that darkness. The lighthearted overtones of the originals, despite their sometimes serious content are simple, with solutions that allow us to sleep easy at night. Where RotJ leaves us crying happy tears, RotS ends with a bitter hope. New, yes, but bitter. Cynical. It’s a level of catharsis that naysayers of the prequels just aren’t ready to accept, because it would mean too much in the context of our own world. Padme’s words are never more true, and this generation of ‘Jedi’ never more blind.

LikeLike

@steelneena agree and that’s why I’m an advocate of the chronological order for the newcomers. Let’s face it, prequels were hurt by our knowledge of the story. It was not about what or who, but how. And the how meant different things to different people, since fans had 16 years to imagine things. TPM and AOTC gain some dramatic urgency when you don’t know the story and ROTS is usually genuinely shocking when all hell breaks loose.

LikeLike

Wonderful write-up. I attempted a shorter form of this overview (including the next/previous trilogy for a look at te full saga) in 2010: http://thedancingimage.blogspot.com/2010/07/notes-on-star-wars-saga.html. I haven’t seem the prequels since then, though I soon will, but I think if anything my view has mellowed even more than the ambivalent, measured disappointment I felt then (already far removed from the newly dominant RLM-influenced hyperbole that characterized prequel discussion at the time). Thanks in large part to Bob Clark’s dogged advocacy I’ve come to greater appreciation of the prequels’ unique accomplishments, amplified by my growing distaste for the OT fanbase’ pathological hatred of Lucas (and as Twin Peaks fan, my frustration with some TP fans’ distaste for their own challenging prequel, which I view as the best part of THAT saga). Not sure yet how this will balance out against the films’ many flaws, which you don’t overlook here, but I am really looking forward to a rewatch.

I think a case could actually be made for Star Wars & Revenge of the Sith as the most rich and compelling, if not *necessarily* the best, of the saga for opposite, almost incompatible, reasons. If you are inclined to give credence to Lucas’ attempts at mythological weight and thematic complexity, then I think Revenge of the Sith has to be considered the centerpiece, maybe the masterpiece. If you are inclined to believe this is overreach on Lucas’ part, that the acting, dialogue, and origin of the narrative are not sufficient to carry such grandeur, then Star Wars (calling it A New Hope would be silly in said context) strikes the perfect balance between childlike enthusiasm and adult sophistication, never taking itself too seriously not descending into adolescent self-parody. (The fact that many who decry the prequels on storytelling choice, rather than executioner excursion grounds, also praise Empire as the SW masterpiece doesn’t make much sense to me; either you think SW can handle tragic grandeur, in which case you at least respect the prequels, or you don’t, in which case ESB has to be dismissed as well). Following the prequels, I leaned much more toward the latter view and hence have been more interested in praising Star Wars as a standalone sui generis accomplishment than a sprawling saga. But several factors have inclined me to re-evaluate or at least amplify that priority.

Sorry for the scattered, reflective nature of the comment but I am typing on my phone with a football game in the background, trying to digest my thoughts! In short, excellent piece that has helped me to home in on some of my own post-TFA musings. Your points about Lucas’ far more expansive frame of references, for both style and content, are particularly appreciated.

LikeLike

I always enjoy it when the comments take on a life of their own. I like Natalie’s comparison of the prequels to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. I also agree that the reuse of the Death Star in ROTJ was cleverer than it was given credit for and certainly cleverer than The Force Awakens. There are aspects of TFA which we won’t, indeed, be able to properly judge until the next instalment. But this bugs me in itself. Star Wars as a narrative style shouldn’t be being made to work like that.

I would sign aboard the theory that fans rejected the prequels for their darker inferences with more assuredness, except that I’m not so confident they paid enough attention to notice.

On a personal note, whenever I revisit the series now, I watch them in the story order. For all its flaws, The Phantom Menace really feels like a starting point.

Joel, I agree with you on the proposition of the split between the first film and Return of the Sith as the two divergent extremes of how one can take the series. Of course, the first one is a grand and hugely enjoyable achievement, but also for me it’s now been entirely changed by the expansion and deepening of the fictional universe, to the point where I still enjoy it but feel it lacks something I seek in the series at points. Obviously, I fall on the side of the mythologians.

LikeLike

To me TPM reminds of both The Hobbit and early chapters of LOTR. The Hobbit, because it’s kids friendly and self contained and the actual plot is less important than certain events that happen during it (i.e. Bilbo finding the Ring vs. Palpatine becoming the Chancellor and Anakind becoming a Jedi padawan).

It’s also like the first volume of LOTR because things are still less epic and dark, there’s a side adventure in the Old Forest complete with Tolkien’s Jar Jar (Tom Bombadil – some fans have a serious dislike towards him and I understand why no film adaptation want to do away with him).

The PT on the whole also reminds me of the Silmarillion because you got demigods and the elite still in charge on both sides and being primary characters as opposed to the likable underdogs like the hobbits or Rebels. Just like the Silm, the PT is more stylized, often birds-eye and cold, with less relatable characters and quite dark.

(Yeah I’m a Tolkien nerd)

Overall it’s a strange mix that doesn’t seem to sit well with many viewers (especially the OT is my childhood crowd). And then there’s a question of expectations. Even if acting/writing was better, the PT would still be highly controversial (although the long gap between the trilogies certainly didn’t help).

LikeLike

Natalie, I fully agree about your comparison of TPM with The Hobbit. The novel, at least. In fact, in my first draft of this essay I made exactly the same point about cutting Tom Bombadil and compared him to Jar Jar (cut for space; this essay’s long enough as it is). So our minds are on parallel tracks. But, as I noted in my review of The Battle of the Five Armies, Jackson’s adaptation of The Hobbit served in a manner more reminiscent of the second two parts of the prequel trilogy – a darker critique of aspects of the beloved first trilogy, one that doesn’t let the Middle-earth denizens off the hook for the diseases in their world that Sauron will exploit so effectively later on. I also think the link with The Silmarillion is correct too; like The Silmarillion, the prequel trilogies are a kind of “high old tragedy” with more formalised and ritualised narratives in contrast with the more boisterous, democratised subsequent instalments.

LikeLike

Wow! Just, incredible. I feel like until now, I’ve never read a real review of the prequel trilogy. Fantastic stuff, sir. Bravissimo! And thank you

LikeLike

Hi Ian. Thanks, but let’s face it, the bar had been set low.

LikeLike

Check this out

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-the-seven-star-wars-films-reveal-about-george-lucas

LikeLike

Yeah, I read that yesterday, Natalie. I found the initial remarks a tad off-putting – it’s churlish to an extreme to complain about urging music scoring in such a genre and I don’t think The Phantom Menace is that much lesser – but needless to say I was in general agreement with Brody when it got to the meat of his argument.

LikeLike

Hi again.

Methinks you are perhaps being modest, about the bar being set low.

I merely want to note that, a vigorous & fulsome critique is not lesser if it has not been done before, or been done, but not well.

Par ailleurs, I enjoyed the depth of the New Yorker article that Natalie references (though, like you, there were aspects of it I did not agree with in the least). But as good as the substance of the piece was, it does not hold a candle to what you’ve written here.

Bookmarked for the purpose of many enjoyable re-reads, and for sharing.

LikeLike

The credits for Ep 3 are rolling as I type this. Watched all three prequels over the last several days and I’m here to declare myself a convert to the pro side. I hadn’t seen them since the theater, when I didn’t much care for them – a feeling that was codified and entrenched by 15 years (plus) of so much wide-spread internet loathing of them. There are lines and moments and a lot of acting that could/should be better, but the sheer guts of the story telling, the movement and detail and dare I say FUN design, and the final linking to the top of A New Hope, all had me thoroughly engrossed by the end. The “homework” you gave me, Rod, helped for sure, but it wasn’t the engine of my new feelings. It was Lucas. He pulled off something here, something deeply entertaining. I’m even willing to lay a bet that future generations will look at these as the better ones. Much like Nixon (yes, him!) will be viewed much less harshly once all those alive in the 70s are dead and gone, the prequels (alien warts and all) will prove to be the more solid, richer go-to faves. The original three are somehow more elemental, maybe that’ll keep them in the running for awhile, but these three build to a much higher emotional peak. I’m flush from the newness of this revelation, so I may be overstating a bit… but probably not by much. I think I’ll always say Empire is my favorite, but that’s so much more for sentimental reasons, if I’m honest with myself. That’s why I say guys like me have to die off before balance is restored in the court of public opinion.

LikeLike

A convert! POWER! UNLIMITED POWER!

I’m just glad you got into the groove of the films and what I was saying, Rob. Indeed, my “homework” was only ever intended as a way of getting in synch with Lucas’ stylisation, which isn’t mere pastiche or tribute. I like your observation about how the prequels build to an emotional peak. Although I’ve mentioned my preference of Return of the Jedi a lot, I think probably the reason Empire still holds so many enthralled is because it does feel like the emotional peak of the first series with Han’s farewell to Leia and Vader’s revelation. Whereas the prequel trilogy builds carefully to a concluding crisis that can only crystallise with everything that’s happened before it. I don’t know what time’s judgement will really bring, but for myself, the achievement of these films was only purified by the surface mimicry and conceptual emptiness of The Force Awakens.

Also, I thought Nixon’s rep was getting worse rather than better with time. But anyhoo…

LikeLike

Not keeping strict tabs on Nixon’s legacy, I just know I’ve heard a lot of commentators, conservative and liberal, who speak of Nixon’s positive contributions with the huge initial caveat of his misdeeds. My feeling is that over time the caveats will get dropped in those sorts of conversations, though they won’t have been forgotten. Just a hunch.

Also, it only dawned on me with your response that I hadn’t mentioned Episode 7. As far as I’m concerned, it has its fun moments, but it’ll have to be a “see it in the context of the next couple” sort of thing before it has any chance at resonance. Currently, not so much.

Mostly, though, I just wanted to be comment #40.

LikeLike

Going back 3/4 of a century Isaac Asimov’s “Second Foundation” SciFi sprawl in the pages of ASF abides!

LikeLike

Star Wars 1-6

A Mythological slice of life micro & macro treatise of

Code-Actions-Feelings

Code-Feelings-Actions

Feelings-Actions

Actions

Actions-Feelings-Code

Feelings-Actions-Code

LikeLike

Perhaps a tip of the hat to “The Prisoner of Zenda”?Black Michael, Rupert et al.?

LikeLike