.

.

Director/Coscreenwriter: Michelangelo Antonioni

By Roderick Heath

Michelangelo Antonioni was a relatively minor figure in the European film scene until 1960. The former economics student and journalist entered that scene in the days of Mussolini’s regime, and started his directing career making documentaries. His early labours offered hues of the oncoming neorealist movement, depicting the lives of poor farmers in Gente del Po (1943), plied under the nose of the dying Fascist state but then lost amidst its collapse. He had the honour of being sacked by Vittorio Mussolini, was drafted, started fighting for the Resistance instead, and barely escaped execution. But when he made his first feature, Cronaca di un amore (1950), Antonioni began to blaze a trail off the neorealist path, following a contrapuntal instinct, a readiness to look into the voids left by other viewpoints, that would come to define his artistry. Although slower to make his name, he nonetheless formed with Federico Fellini the core of the next wave of Italian filmmakers. Antonioni helped write Fellini’s debut film The White Sheik (1951) before he made his second feature, I Vinti (1952), a three-part study of youths pushed into committing killings, a sketch for Antonioni’s recurring fascination with characters who barely know why they do what they do. Antonioni’s sudden ascension to cause celebre and acclaimed director had to wait, however, until his L’Avventura (1960) screened at the Cannes Film Festival. This remains one of the legendary moments in the festival’s history, as the film was met by jeers and anger from some of the audience and greeted as a ground-breaking masterpiece by others. L’Avventura took on a relatively obvious but powerful idea: what if you set up a film as seemingly one kind of story, then changed tack, refused to solve the mystery presented, and used the resulting discord and frustration to infer a different, more allusive meaning?

.

.

Antonioni sold this idea as something like a Hitchcock film without the suspense sequences and reduced to the studies in emotional tension Hitchcock usually purveyed under the cover of such gimmicks, with rigorous filmmaking and an antiseptic approach to his characters’ private obsessions that left them squirming without recourse before his camera. Antonioni was now hailed as the poet laureate of “alienation” cinema, a filmmaking brand digging into the undercurrent of detachment, dissonance, and unfulfillable yearning lurking underneath the theoretically renewed, stable, prosperous world after cleansing fires of war allowed the ascent of modernity. His was the intellectual, continental, Apollonian side to the same phenomenon observed in the more eruptive youth films in the U.S. and Britain like The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955); eventually Antonioni would try to unify the strands with Zabriskie Point (1970). Antonioni followed his breakthrough with two films to complete a rough trilogy, La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962), and his first colour film, Il Deserto Rosso (1964). For Blowup, he shifted to London and its burgeoning “swinging” scene. Blowup, like L’Avventura, superficially repeats the gimmick of setting up a story that seems to promise regulation storytelling swerves, and then disassembles its own motor. Blowup’s murder mystery seems designed to point up a cocky young photographer’s defeat by ambiguity and lethargy and the dissolution of his own liminal senses. Or does it? Again, there was a Hitchockian side to this, taking the essence of Rear Window (1954) and its obsessive correlation of voyeurism with filmmaking, whilst inverting its ultimate inference. But Antonioni took his motivating concept from a story by Argentine author Julio Cortazar, “Las babas del diablo,” based around a man’s attempt to understand a scene featuring a pair of lovers and a strange man he spots in the background of photos he takes of Notre Dame.

.

.

Cortazar’s main character became lost in the unreal space between the photo and his own imaginings, projecting his own anxieties and emotional biography onto the people he inadvertently captured, particular his sexual apprehensions. Antonioni skewed this template to serve his own purposes and to reflect the strange new zeitgeist festering as the 1960s matured. The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 sent ripples of profound disturbance and paranoia through the common experience. Conspiracy theorists began scouring photographic evidence for evidence to support their claims even before the Zapruder film came fully to light. Antonioni tapped into a percolating obsession, which joined also to a growing mistrust of public media at large, by reconstructing the central motif of Cortazar’s story to become one of apparent murder—perhaps an assassination. But Antonioni had been delving into some other ideas present in Blowup since his career’s start. I Vinti contained one story set in London, depicting a shiftless young poet who discovers a dead body and tries to sell the story to the press: there already was the peculiar ambiguity of approaches to crime and the weird mix of venality and empathy that can inflect the artistic persona. Antonioni seems not to have lost the reportorial instinct honed in his documentary work. Like Dostoyevsky, he took on tabloid newsworthy stories about murder, vanishings, delinquency, and the sex lives of a new class jammed just between the real masters of society and its real workers. He followed such lines of enquiry through the social fabric of his native Italy at first, and then out into the larger world.

.

.

The aura of abstract elusiveness Antonioni’s works give off tends to disguise how much they are, in fact, highly tactile films, defined by an almost preternatural awareness of place, space, and décor, constructing mood and inferring meaning through the accumulation of elements. Where Fellini increasingly celebrated the inner world and the furore of the individual perspective in the face of a strange and disorientating age, Antonioni became more interested in the flux of persona, the breakdown of the modern person’s ability to tell real from false, interior from exterior, even self from other, and had to find ways to explain this phenomenon, one that could only be identified like a black hole by its surroundings. Cortazar’s protagonist, moreover, was a writer who also dabbled in photography. Antonioni made his central character, Thomas (David Hemmings), a professional photographer whom he based on David Bailey, quintessential citizen of Swinging London, an angry Cockney kid who became the image-forger of the new age. Thomas’ sideline in harsh and gritty reportage from the edges of society for a book on the city he’s working on—he’s first glimpsed amongst a group of homeless men he’s spent the night taking clandestine shots of—suggests Antonioni mocking his own early documentaries and efforts at social realism. Thomas has a side genuinely fascinated by the teeming levels of life around him, but in a fashion that subordinates all meaning to his artistic eye and ego. He shifts casually from wayfarer amongst the desperate to swashbuckling haute couture iconographer, engaging with haughty model Veruschka in fully clothed intercourse, and irritably bullying another cadre of models until he gets fed up, projecting his own tiredness and waning interest onto them, and walks out.

.

.

Thomas takes time out with his neighbours, painter Bill (John Castle), and his wife Patricia (Sarah Miles): Thomas takes recourse in Patricia’s wifely-maternal care now and then, whilst Bill stares at his old paintings and explains that he has no thoughts whilst making them and only finds hints of meaning later, a statement that recalls Antonioni’s own confession that he approaches his works less as systematic codes than as flows of epiphanies eventually gathering meaning. Thomas is nakedly on the make, a businessman-artisan who longs for wealth to become totally free. He has designs on making a real estate killing, hoping to buy a mangy antique store in a rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood (“Already there are queers and poodles in the area!”) from its young owner, who wants to sell up and hit the seeker’s trail to Nepal. Wasting time before the store’s owner returns, Thomas starts clicking snaps in a neighbouring park, eventually becoming fascinated by an apparently idyllic vignette of two lovers sharing the green space. The woman (unnamed on screen, called Jane in the credits, and played by Vanessa Redgrave), who’s much younger than her apparent lover, spots Thomas and chases after him with a frantic, breathless desire to obtain his pictures. Thomas haughtily alternates between telling her he needs them—he immediately sees how to fit them into his London panoramic, as the perfect quiet diminuendo from all the harsher facts on display—and promising their return, but is surprised later on when she actually turns up at his studio. There have been signs that she and an unknown man might have been trailing him around the city, including watching him during his lunch with his agent, Ron (Peter Bowles).

.

.

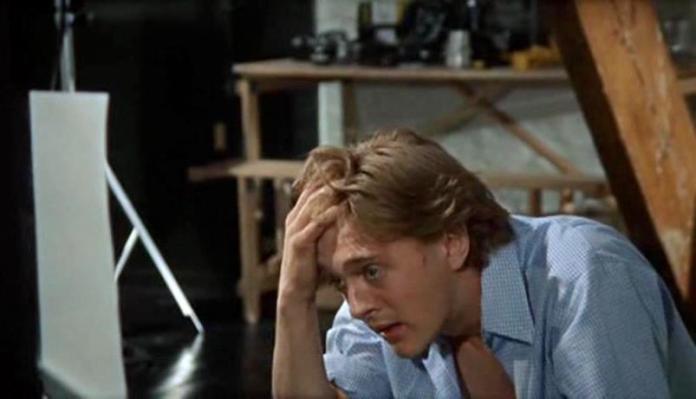

Thomas’ studio, usually a scene where his will reigns, now becomes a kind of battleground, as Thomas, fascinated by Jane’s manner, at once nervous and uncomfortable but also sensual and self-contained, keeps using promises of the photos to get her to stick around; she, desperate to obtain the pictures, tries using sex appeal to prod him into submission. The two end up merely circling in a toey, searching dance (albeit with Thomas briefly schooling Jane on how to move to Herbie Hancock’s jittery grooves), their actual objectives unstated. Jane’s pushy determination arouses Thomas’ suspicions, so he allows her to finally dart off after trading her scribbled, fake telephone number with a roll of film—a blank roll in place of the one she wants. Thomas then begins studying the pictures of her and her lover in the park. Slowly, with a relentless and monstrous intimation, Thomas begins to see signs that far from being a romantic tryst, he was actually witnessing an intended crime, with Jane acting as the honey trap to bring the man to the scene, whilst her unknown partner lurked in the bushes with a gun. At first, Thomas thinks hopefully that his presence foiled the killing, but on looking even more closely, realises the target had been gunned down whilst he was arguing with Jane, or is at least apparently lying motionless on the ground. “Nothing like a little disaster for sorting things out,” Thomas says with glib, but minatory wisdom to Jane, in reply to her cover story about why she wants the pictures. Eruptions of irrational occurrence and suddenly, primal mystery in Antonioni’s films don’t really sort anything out, but they do tend to expose his characters and the very thin ice they tend to walk on.

.

.

Like the punch line to a very strange joke, Blowup became a pop movie hit, mostly because it became prized as a peek into a scene many were fascinated by and fantasised about, and the allure of that moment, captured forever in Antonioni’s frames, now precisely a half-century old, still lingers in exotic fascination for many as time capsule and aesthetic experience. Blowup’s strangeness, implicit sourness, and assaults on filmic convention might even have helped its success, the aura of shocking newness it exuded perfectly in accord with the mutability of the moment. The ironies here are manifold, considering Antonioni’s insinuation that there’s no such thing as the sweet life and that cool is a synonym for wilful ignorance. One could suspect there’s a dash of the dichotomy apparent in Cecil B. DeMille’s religious epics, plying the allure of behaviour the moral framework condemns. But that would come from too glib a reading of the total work, which, in spite of its stringent evocation of a helpless state, is a lush, strange, attractively alien conjuring trick, a tale that takes place in a carefully cultivated version of reality, as much as any scifi or fantasy film. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) perhaps owed something to its patient, subliminal method and seeming ambling, but actually highly controlled form. Hitchcock himself was transfixed by it. Its spiritual children are manifold, including not just Brian De Palma and Francis Ford Coppola’s revisions on its themes (The Conversation, 1974; Blow Out, 1982) and attempts by later Euro auteurs like Olivier Assayas (demonlover, 2002) and Michael Haneke (Cache, 2004) to tap into the same mood of omnipresent paranoia and destabilised reality, but more overtly fantastical parables like Logan’s Run (1976) where youth has become a total reality, death spectacle, and nature an alien realm, and The Matrix (1999) where the choice between dream and truth is similarly fraught. There was often a scifi quality to Antonioni’s films, with their sickly sense of the landscape’s colonisation by industry and modernist architecture like landing spaceships, the spread of a miasmic mood like radiation poisoning, the open portals in reality into which people disappear.

.

.

Blowup is a work of such airy, heady conceptualism, but it is also ingenious and highly realistic as portraiture, a triumph of describing a type, one that surely lodged a popular archetype of the fashion photographer in most minds. Thomas is a vivid antihero, but not an empathetic one. In fact, he’s a jerk, a high-powered, mercurial talent, a bully and a sexist with hints of class anger lurking behind his on-the-make modernity given to ordering his human chess pieces how he wants them. Hemmings, lean and cool, the fallen Regency poet and the proto-yuppie somehow both contained in his pasty frame, inhabits Thomas completely. When he and Redgrave are photographed shirtless together, there’s a strong erotic note, but also a weird mutual narcissism, as if both are a new species of mutants Antonioni can’t quite understand that will inherit the earth, able to fuck but not reproduce. Thomas seems like a glamorous, go-get-’em holy terror for much of the film, a study in prickish potency and constant motion—perhaps deliberately, he’s reminiscent of Richard Lester’s handling of the Beatles in places, the free-form artists at loose in the city with a slapstick-informed sense of action. But Thomas slows to a dead stop and fades away altogether by the film’s end.

.

.

Space is the subject of a silent war in Blowup. Within his bohemian studio Thomas is king, able to construct a world that responds entirely to his needs. Antonioni uses its environs to create a system of frames within frames, subdividing his characters and their interactions. Thomas’ ambition to annex the antique store represents a desire to expand a kingdom, and he roams through London keen to the process of the homey old city putting on a new face, whilst energetic young students engaged in the charity ritual known as the “rag” dress as mimes and roam at loose, claiming everything as their own. The empty public facility of the park becomes, ironically, a cloistered space to commit a murder. Later, when Thomas returns to the spot, he finds the victim’s body still sprawled, pathetic and undiscovered, upon the greenery. “He was someone,” is all Thomas can bleat at one point as he tells Patricia about the business, indicating both his bewildered lack of knowledge about the man to whom he’s been left as the last witness, and also his forlorn realisation that the man’s death is the mere absence of his being.

.

.

The giant airplane propeller Thomas buys from the antique store delights him, a relic of technology, the promise of movement now purely a decorative motif for his studio. Thomas craves freedom, but has no sense of adventure: “Nepal is all antiques,” he tells the store owner when she says she wants to escape her wares and their mustiness. Thomas’ talent has made him a magnet for wannabes, a fetish object himself in minor celebrity. His curiosity for Jane, with her intensity pointedly contrasts his insouciance towards two would-be models (Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills) who come hoping for a shooting session, but essentially become a pair of temporary houris for the flailing macho artist. The sequence in which Thomas is visited again the two girls, known as only as the Blonde and the Brunette, sees Thomas revealing a scary side as he monsters the Blonde, only for this to quickly transmute into a gleefully childish, orgiastic moment as the three wrestle and fuck on the floor of the studio. Afterwards, the two girls worshipfully put his clothes back on. For them, it’s a graze with success in all its filthy glory and a moment of holy obeisance to the figure of mystical power in the new pop world. For him, it’s a moment of barely noticeable indulgence, a distraction from the far more interesting mystery before him, which in itself stirs a need in him he barely knows exists, like Jane herself. During their long scene together, Thomas pretends a phone call, possibly from Patricia, is from his wife, apparently just to tease Jane. He casually invents a history and a home life that he then completely revises until he’s left in honest limbo. The image of elusive happiness of Jane and the man in the park and the mystery of Jane stirs a wont—and then proves a total illusion, a siren call to annihilation.

.

.

The film’s crucial movement, a high point of cinema technique and style, comes as Thomas investigates his pictures. He zeroes in on anomalies and blurry, seemingly meaningless patches, even the inferences of his “actors”’ body language, and marks out points of interest and uncertainty. He then makes new prints blowing up these spots. Each reframing and zoom is a partial solution to the last puzzle and the start of a new one, until his studio is festooned with what seems an entire story, which Antonioni can now move through like a primitive flipbook protomovie. It’s a miniature film theory class, a lesson in constructing to elucidate a reality that would have otherwise been missed in the clumsy simplicity of human perception. It’s also a journey in transformation, turning the idyllic moment Thomas prized so much into a menacing and terrible opposite, and dragging Thomas himself through alternating states of obsession, pleasure, depression, and finally nullification, the film character invested with the same alternations of emotion and perception as the audience watching him.

.

.

Blowup fades Thomas out before it fades out itself, and his subjects are revealed as even stranger than they seemed: Jane’s frantic attempt to ward him off, the man’s slightly sheepish, slightly haughty disinterest. In both readings of the situation, something shameful is happening. The lurking killer’s posture and shadowiness are reminiscent of Reggie Nalder in Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), but the thunder of Hitchcockian climax has been replaced by the shimmering, Zen-touched hiss of the trees. The aesthetic key comes from Bill, an artist working in a purposefully diametric medium, the man trying to make form out of his own strange chaos, even stating, perhaps superfluously, that it’s like tracking a clue in a detective story. The two art forms collide, mingle, reforge. Aesthetic is no longer décor, but challenge, way of being, even a danger.

.

.

What was profoundly disturbing in Antonioni’s moment has become a playful norm. Today, the manipulation and transformation of images, usually for trivial purposes and day-to-day entertainment, is commonplace. YouTube is crammed with ingeniously faked reels of monster sightings. Anyone who’s worked on retouching a picture with Photoshop has been through the experience of Thomas seeing, say, the eye of a beautiful woman turning into a swirling galaxy of colours and then an array of completely abstract cubes. The difficulty of manipulating film, with its complex chemical properties, has given way to the perfectly malleable states of digitisation. The idea that photographic evidence can automatically or even momentarily be granted complete trust is archaic. Cinema verite gave way to reality television. More seriously, huge amounts of time, energy, and bandwidth have been devoted by some to investigating footage of the moon landings and the 9/11 attacks for proof of conspiracy and mendacity, often provoking staggering incredulity over how different people can look at the same thing and interpret it in vastly different ways. Antonioni was looking forward to our time even as he rooted his film in the mood of a particular time and place—the saturation of the image and the charged, near-religious meaning it takes on in spite of being evidently profane. Many in his time saw a Marxism-inflected, Sartre-influenced meaning in his work as diagnoses of the eddying feebleness that descends when political and social motivation are subsumed by a meaninglessly material world. This was almost certainly an aspect of Antonioni’s thinking, though it also feels reductive: like all art, it wouldn’t exist if what it said could be summed up in a pamphlet. The experience itself is vital, the passage its own reality..

.

Thomas’ ultimate confrontation is not simply with impotence, but also with the vagaries of experience itself, as all proof of his experience vanishes and with it, assurance it ever happened. Antonioni toys with the idea that revealing the truth is only a matter of looking closely and seriously enough for something, but then undercuts it, suggesting that on a certain level, reality breaks down, or perhaps rather like the sense of matter in subatomic particles, is displaced and transmuted. Thomas becomes half-accidentally the witness to a murder, not just because he sees it, but because his merely human memory is the only repository for it after his photos and negatives are stolen. Once the murder’s done there’s no real purpose to action, something his “he was somebody” line again underscores—the only real spur to intervene in a crime is to prevent it, whereas anything afterwards is only fit for an undertaker. Thomas finds the man’s body in the park, but the drama’s over. He can’t do anything except try to enlist Ron to give independent testimony to his witnessing. Perhaps, far from simply accusing contemporary artists and audiences of ditzy political detachment, Antonioni was most urgently trying to portray his experiences as a filmmaker, his attempts to capture raw and unvarnished truths on film and then seeing that truth dissolve because of the vagaries of life and the medium shift under study. At the same time, Antonioni imposed rigorous aesthetic choices on his creation, going so far as to repaint houses in the streets where shooting took place to communicate interior states through exterior sign play: he had become an imperial creator even as he mocked his own ambitions.

.

.

The famous performance of the Yardbirds towards the end of the film in which Jeff Beck smashes his own guitar is crucial not as a mere indictment of a slide into neon barbarianism many of Antonioni’s generation saw in the rock ’n’ roll age, though that note does sound, but also a summary of Antonioni’s confession. Here is an artist’s anger with his art and his tools, his sense of form and purpose breaking down in the increasingly nettled sense of what to say and how to say it in the face of a modern world slipping away from any coherent design of understanding. The hip audience watch mostly with faces of stone, happy to let the artists act out their feelings, sublimating temptations towards excess, destruction, anarchy. Although Antonioni’s recreation of the mood of the time was the very opposite of the florid unruliness we associate with the era’s cultural scene, there’s definite sense and accuracy to his portrait, his understanding of the underlying psychic transaction. This scene converts the film’s larger experience into a jagged epigram.

.

.

Thomas needs and uses the mystery he uncovers to shock himself out of a stupor, only to find it doesn’t transcend his situation, only exemplifies it. The film’s last few reels turn into a dumbstruck odyssey for Thomas as he seeks Ron to take him to see the dead body, but is distracted by seeing someone he thinks is Jane enter a mod concert venue. He ventures into the concert looking for Jane, whose brief seeming appearance and then disappearance is one of Antonioni’s finest sleights of hand, and comes out instead with the guitar’s neck as a battle trophy, like the two models with him earlier, for the attention of the famous, only to toss the trophy away, its momentary totemic power spent. He then tracks Ron to a posh party where everyone’s doped to the gills and can barely lift a finger in response to Thomas’ news.

.

.

Some complained at the time that Antonioni’s tendency to find the same qualities in the countercultural youth and bohemians he studied in Blowup and Zabriskie Point as he did in the tepid bourgeoisie of Rome was wrongheaded and phony. But time eventually proved him right in many ways. There’s a cold, mordant honesty to the sequence in which Thomas sits watching a bunch of bohemian toffs getting high, the new lotus eaters buying out of a reality they’ve barely glimpsed anyway, faintly anticipatory of Kubrick’s historical wigs with people underneath in Barry Lyndon (1975), glimpsed in Restoration artlike friezes, and grindingly familiar to anyone who’s been surrounded by very stoned people at a party. Thomas’ resolve dissolves amongst their uninterest and his own exhaustion. He awakens the next morning, restored but now with the grip on his fever dream lost.

.

.

The closing scenes provide a coda much like the one Thomas wanted for his book: perhaps he’s projected himself after all into the zone of his fantasies, a state of hushed and wistful melancholy. Thomas finds the body gone. The drama he happened upon has now dissipated, replaced by the gang of students who have been crisscrossing his path since the start, making up their own realities. Tellingly, these characters are the only ones who have ever made Thomas smile. Thomas finally finds solace, or something, joining in, to the point where the sounds of a real tennis match start to resound on the soundtrack to accompany the fake one the mimes are playing. It’s easy to read this as the final collapse of Thomas’ sense of reality, but it’s also the first time he simply stands and experiences without his camera, his interior reality allowed scope to breathe. Perhaps what we’ve witnessed is not the defeat of the artist but rather a rebirth.

Great analysis, and it brought back memories of the film, and in retrospect, greater understanding. There was a sort of parallel movie in the 70s, ‘The Conversation’ that dealt with sound rather than visuals. Starred Gene Hackman. It wasn’t nearly as interesting or thoughtful as ‘Blowup’, more a straightforward thriller. But basically the same story, only in what is heard, not seen. And there was one good scene with Hackman walking through Union Sq. in San Francisco with a mime mocking his every move.

LikeLike

Hi John. Yes, I did allude to The Conversation in the essay. Some adore it and say it’s Francis Coppola’s best. I do think it’s very good, and I wouldn’t call it a straightforward thriller exactly – it’s nearly as ambiguous and lacking thrills as Antonioni’s work – but I also feel it’s a touch laboured in places and works against the grain of Coppola’s usual artistic impulses in a manner that does feel artificial.

LikeLike

Thanks! I should have read more carefully!

LikeLike

I have a question and since Roderick’s taste in movies over the years has become one that I both lean on and respect, this is the best forum to clear my chest on an issue that I have felt some intellectual shame over for many years. I came to the work of Michelangelo Antonioni through my love of Stanley Kaufman, the great film critic at the the New Republic. I fell in love with both “Blow Up,” and “L’Avventura,” as a fairly young man in my mid teens. They are both films I could watch again tomorrow if they were playing somewhere.

I never got the rest if his career though. “La Notte” and “Red Desert” were both almost un watchably boring to me. “The Eclipse” and “The Passenger” had great ending sequences (the first a montage, the second a long, sustained shot) but seem like empty melodramas about people we had no chance of caring about and who spoke in platitudes that made me question my love of both “Blow Up,” and “L’Avventura.” So was Antonioni a glorified soap opera director who struck gold twice and made films that hit me on a viseral level which made me ignore their other flaws? Or am I missing some deeper meaning in these films of his that I rate to be as boring and awful as some of the worst movies I have ever sat through? I exclude “Zabriskie Point” because it was so awful that it seems unfair to bring into an Antonioni conversation. Was he a two trick pony or am missing something?

LikeLike

Eric – I realize you’re asking Rod this question, but I have a few things to say about Antonioni, specifically La Notte and The Passenger, the former I consider flawed, but worthwhile and the latter, a masterpiece. Oh, and Le Amiche, an early, developmental film, just for good measure.

LikeLike

Thank you Marylin. I posed the question to Roderick simply because he wrote the article of course and it was very kind of you to add your input. After reading all three of your retrospectives you left links for, I realize that there is something I am missing in Antonioni’s other films. To my eyes they are ennui for it’s own sake.

Your excellent plot summeries only served to remind me if just how bored I was watching the movies in the theater. Imagine if an even slightly less dour director (or one with any sense of humor whatsoever), had worked with the same material? Imagine if we were allowed to care about even one of the charactars? Think of what Luis Buñuel could have done with “The Passenger!”

LikeLike

I find Antonioni less convincing when he gets more emotionally involved with his characters. I always appreciate his stance that people are mysteries to each other. Everyone talks about how normal a killer seemed before he shot up a fast-food restaurant, or how shocked they are when “the perfect couple” split up. We don’t really know what goes on in the minds and hearts of those around us, and even the massive connectivity of the internet has not changed that – in fact, I think it has exacerbated it because people believe they know more than they do just because they can do a Google search or follow a celebrity on Twitter. I think Antonioni’s ennui is not for its own sake, but for ours. He sounded a clarion call for what was to come and confronted us with our own imperfect knowledge of our fellow human beings. He’s not warm, like Bunuel, in his regard for humanity (though I’d argue that Blowup shows more of a concern for others than many films today do), but his method is to confront us with our alienation. Can it be boring? Obviously, it can. I never feel that way when I watch his films.

LikeLike

Marylin – very well put. Antonioni movies are all about surfaces. My question is answered. I have always found his work frustrating shallow. I was bored because I didn’t care. In a way that was his point. I still won’t go watch “Red Desert” again but I now I understand why people whose opinion of a film I detested have such a different opinion of his work.

LikeLike

The thing with THE CONVERSATION is that it seems to me that it only really uses the basic premise of BLOWUP as a jumping off point and that Coppola takes a more cerebral approach to the material whereas Antonioni strikes me as a sensualist in this film.

I last watched this late one night and the gradually oppressive ominous feeling really put the zap on me in a way that it never had before. I think that the paranoia and dread that Thomas experiences is expertly ratched it up gradually over time until it feels almost unbearable towards the end. I felt the urge to turn on lights and quickly watch something lighter. BLOWUP had never affected me like that before and I was struck by it. Such a great film.

LikeLike

Great comment there, JD. I had a similar feeling recently when I watched this, Red Desert, and La Notte in fairly close proximity; particularly with Red Desert, I had the feeling Antonioni was mapping my current mental landscape with excruciating accuracy. His ability to actually illustrate a way of feeling rather than merely having characters state it is like a form of dark art.

LikeLike