.

.

Director: Jim Sharman

By Roderick Heath

Incredible as this will sound, this week I watched The Rocky Horror Picture Show from beginning to end for the first time. Oh, sure, I’d seen most of it in bits and pieces before going right back to when I was a kid. Thanks to growing up in a pop-culture world inflected with its legacy, I was long familiar with its characters, plot, and, of course, its soundtrack—who hasn’t heard “The Time Warp” or “Sweet Transvestite” in our day and age? This very familiarity made seeing the whole thing seem a bit superfluous, but finally, I made myself sit down and take it all in.

.

.

Rocky Horror was, of course, struggling British-born, New Zealand-raised actor Richard O’Brien’s brainchild, composed, he said, to keep himself busy on long winter evenings of unemployment. O’Brien’s off-the-wall musical play mashed up his fetish for classic scifi and B horror movies, the trappings of the faded ethos of showmanship and glitzy-tacky Hollywood pizzazz, and the milieu of post-Swinging London and the age of sexual liberation—all entirely in keeping with a music scene ruled over by Mick Jagger and Ziggy Stardust. Australian theatrical director Jim Sharman, who had gained some respect for his staging of Jesus Christ Superstar, knew O’Brien from his one-night stint playing Herod in the show, and O’Brien snagged his interest with his kooky project.

.

.

Sharman’s showbiz pedigree was unquestionable. His father had been famous in Oz for running a travelling boxing show and carnival, and he grasped the potential in O’Brien’s project. He had already directed a film in Australia, 1972’s Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens, built around much the same mix of nostalgia, camp, music, and satirical reference. Sharman staged O’Brien’s show in the 64-seat Royal Court Upstairs Theatre with a cast of virtual unknowns, including star Tim Curry, an actor O’Brien knew from around his neighbourhood, and Sharman’s pal from down under, “Little” Nell Campbell. The show was an instant success, and soon became the fixture it essentially still is. Two years later, Sharman brought it to the big screen for 20th Century Fox, importing for the sake of a larger budget two American actors, Susan Sarandon and Barry Bostwick, to play the nominal leads, as well as one talent who had made an impression in the LA production, Marvin “Meat Loaf” Aday. The film version initially failed to find an audience, and was written off as a misbegotten flop, but this was the golden age of cult films, with midnight screenings of cinematic oddities attracting large audiences of college kids and hipsters. An enterprising distributor saw the potential in marketing the film to the same audience, and soon a whole subculture formed around the movie, with audiences creating a ritualised script of comment and response and live performers mimicking onscreen action.

.

.

It’s easy to see Rocky Horror’s specific appeal, particularly in the milieu of the mid-1970s. Above all, the rock ’n’ roll score accomplished something nothing, not even Hair or Jesus Christ Superstar, had quite pulled off so effervescently and effectively before (or, really, since, perhaps not until the recent Hamilton)—contextualising the stage musical in the pop era in a way that made it fit. O’Brien tapped into an audience steeped in both a love of flimsy fantasy and New Age mores, creating a variation on a niche of gay culture just acceptable enough to lodge itself in the mainstream. The plotline, whilst strutting through a mocking pastiche of B movies, essentially describes a mass cultural experience, portraying a pair of hopeless squares being exposed to the stranger side of life and finding themselves, if not necessarily better off, certainly wiser—a Sadean narrative rendered in a light, fun, mostly harmless manner. At the same time, Rocky Horror has undoubtedly helped a lot of gay, bisexual, and just plain fabulous people come out of the closet and wield its fantasy as a weapon.

All that said, though, is The Rocky Horror Picture Show any good?

.

.

As a record of this peculiar cultural artefact, certainly. The movie, like the stage version, opens with the song “Science Fiction/Double Feature,” an ode to the pleasures of cinema from yesteryear, the stuff of O’Brien’s youth, referencing the likes of Tarantula (1955) and Day of the Triffids (1962). The film is littered with references to the glory days of Hollywood filmmaking, and there’s an interesting contradiction in there somewhere, this creation of fringe art celebrating a lost Eden of commercial art—although in the context of the mid-’70s, that legacy had faded and the same studios were trying to reinvent themselves by making stuff like, well, stuff like Rocky Horror. Moreover, such referential gambits feel like a miscue to me, as the project never really settles for pastiche or lampooning, and, least of all, for straight-up genre thrills, but instead subjects those tropes to a transmutation, turning subtext inside out and exploring less the ideas of classic genre cinema than camp culture’s take on it. Sharman’s expanded cinematic scope and the production circumstances allowed him to directly evoke the glory days of British cinefantastique, particularly Hammer horror, which was in its death throes at the time. Much of the film was shot around the decaying Oakley Court mansion, a popular location for horror film shoots. The central scene of monstrous creation directly references the laboratory scenes of Fisher’s Frankenstein films.

.

.

One of the cleverest touches of the film adaptation was casting Charles Gray, consummate player of villains in such films as Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out (1967) and the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever (1971), as a “Criminologist” whose introductions and narration evoke the likes of Edgar Lustgarden, the crime writer famous for hosting true crime TV series in the ’50s, and Boris Karloff’s hosting of the anthology show Thriller. Some of the film’s truly killer vignettes include the cutaways to him lecturing on how to do the Time Warp, and casting away his dryly portentous dignity to dance on a table top. Drive-in movie fare isn’t the only subject for satirical mirth: Brad and Janet overhear Richard Nixon’s resignation speech, symbolic fall of the establishment about to be mirrored by the young couple’s impending date with subversive elements.

.

.

An early sight gag unsubtly, but pertinently lampoons the couple representing middle American values, as Grant Wood’s famous “American Gothic” painting looms over protagonists Brad Majors (Barry Bostwick) and Janet Weiss (Susan Sarandon) and their friends at a wedding. The inference is obvious, the lurking spectre of parched, repressed, cheerless conformity the legacy behind their white-bread, upright, uptightness, and several of the church congregants watching the wedding revels with parsimonious intensity are, in fact, the very same perverts who will later turn the couple’s lives upside down. Brad and Janet are citizens of the Texas town of Denton. After they bid farewell to their just-married friends, Brad finally confesses his love for Janet via the song “Dammit Janet,” and they set off for a night of celebrating their smouldering blandness. But the couple’s journey is complicated by a storm and strange motorcyclists, and their car busts a tyre after they take a wrong turn. Luckily for them, there’s a castle nearby where they can ask for help.

.

.

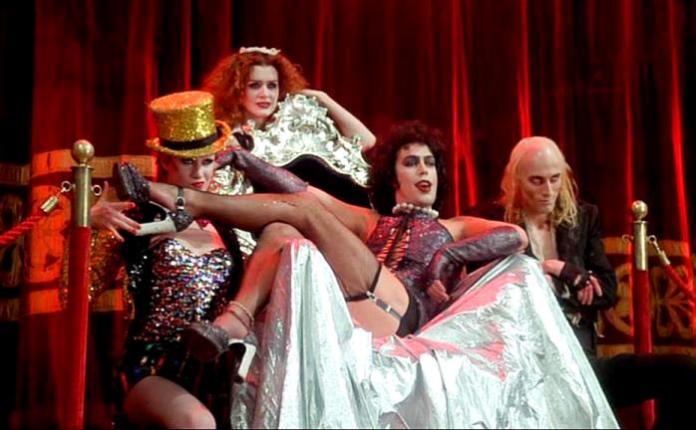

Brad and Janet immediately stumble into an asylum of weirdness, greeted by a cabal of partying oddballs attending the “Annual Transylvanian Convention,” overlorded by pansexual, transvestite scientist Frank-N-Furter (Curry) and his fake servants, hunchbacked butler Riff Raff (O’Brien) and his sister and maid Magenta (Patricia Quinn), as well as hanger-on and former lover Columbia (Campbell). Frank has gathered the cabal together to celebrate the culmination of a great experiment: he is about to bring life to a man he’s constructed, dubbed Rocky (Peter Hinwood). Frank’s creation emerges from the vat as a perfect Aryan vision, ready and willing to flex his physique to the amazement of the audience even as he wonders what strange situation he’s been plunged into. But Frank’s road to triumph has been paved with his sins, including frozen biker Eddie (Meat Loaf), who busts out of cold storage in a dizzy rage. A delivery boy who was ensnared by Frank’s lustful attentions but who gravitated to Columbia, Eddie’s been partly harvested to provide Rocky’s brain, and he careens through Frank’s lab on his motorcycle until the vengeful host dispatches him gorily with an ice pick. Having disposed of this momentary distraction, Frank sets Rocky to building up his body to ever greater heights of masculine glory before chaining him to his bed. Rocky Horror revolves around this one central, inarguably brilliant premise—though the film doesn’t do much interesting with it—turning the classic Frankenstein figure into a freak who wants to create not just a human being, but a perfect male love object and then doubling down on this joke by having the monster’s traditional rebellion be that he is resolutely and helplessly heterosexual.

.

.

Curry inhabits the role of Frank-N-Furter with such total ease and charismatic verve that it seems like he was born in his lofty stilettoes and garters, credibly locating jolts of pathos and flickers of melancholy under the surface of a creature otherwise defined by totally shameless hedonism and dedication to his own outsized talent and ego. From the moment he enters the film dressed like Dracula, only to throw off his cape and reveal his very masculine body swathed in burlesque-ready underwear, Frank-N-Furter commands the proceedings. Later, as he acts as impresario mad scientist at Rocky’s revival, he sports the pink triangle of gay pride (adapted and reversed from a Nazi designation), but doesn’t stop at any polite or merely political limits of gender orientation. The figuration of Frank and Rocky could well have been originally inspired by Z-Man and his lust object, Lance Rocke, in another hugely popular camp relic, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970); Frank very strongly recalls Z-Man as the imperious host of debauched revels and jealous creator with not-so-secret peccadilloes. There’s also a strong whiff of Cabaret’s (1972) Emcee to him, and Bob Fosse’s sleazy-sexy sensibility pervades the film as an influence.

.

.

Sharman’s theatrical talent mostly works once Brad and Janet reach Frank’s castle and are confronted by an the alternate-universe rock’n’roll party as a moment of revelation. The Transylvanians line-dance, and Riff-Raff, Magenta, and Columbia regale them with “The Time Warp,” that most insistently catchy and seemingly nonsensical of songs with lyrics that bespeak a defining obsession with nihilism countered with a sense of freedom and release found in remembered pleasures. Frank enters from a cage elevator and struts through the scene with carelessly convivial enthusiasm laced with erotic potency. The movements here obey their own warped logic, the mood of having stumbled through veil into a strange zone of reality, true in its way to many a classic horror film with the twist of discovering not horror and madness—although there is some of that—but rather the strangely alluring invite of a secret society dedicated entirely to making life a trifle less dull. Of course, it’s the songs here that tie this act together: “The Time Warp” segues into “Sweet Transvestite,” and, a little later, “Hot Patootie,” all musical bits that roll on with driving force, the first and the last perfect floor-fillers and the middle song an impudently sexy declaration of Frank’s wont that burrows deeply into the ear.

.

.

The stage is set for wild and shaggy times, and some do actually happen. Very much the pivotal sequence of Rocky Horror and its mystique comes at the halfway mark in a sequence that plays as an omnivorous replay of the health clinic scenes in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), except whereas James Bond was fox in the henhouse with a bunch of horny ladies, here Frank-N-Furter revels in having a couple of ripe, young dweebs to make a tilt at. Frank first pretends to be Brad visiting Janet and then Janet visiting Brad, with both squares letting him have his way with them on the assurance the other won’t find out about it, climaxing, literally and figuratively, with the silhouetted, but still declarative shot of Frank fellating Brad, a moment that does still feel gutsy and unique in the context of such a work of broad appeal.

.

.

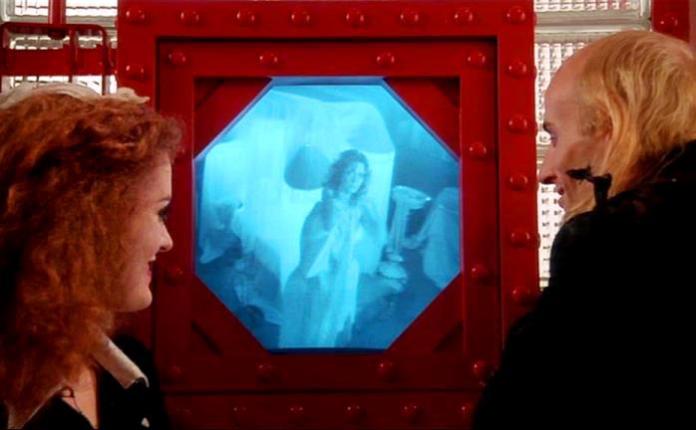

Riff Raff and Magenta’s general program of torment and sabotage sees them drive Rocky crazy with fire and cause him to escape, and then make sure Janet can see through the house’s TV monitors that Brad and Frank are together. Janet stumbles out in an anguished delirium and meets Rocky. She succumbs immediately to his boy-man virility, a spectacle that, in turn, shocks both Frank and Brad. Eddie’s father, a scientist named Everett Scott (Jonathan Adams) and a rival of Frank’s, reaches the castle in search of his son, necessitating a very uncomfortable dinner that climaxes with Eddie’s dismembered body being revealed in a glass coffin under the banquet table.

.

.

Unfortunately, Rocky Horror leaves itself no particular place to go after Frank’s bout of bed-hopping, and in the above-described scenes, retreats into shtick that, frankly, could be in any average dinner theatre show (“Or should I say Von Scott?” Gimme a break). The odd witty line does drop throughout the film—I got a good laugh from Brad’s question, “So, do you any of you guys know how to do the Madison?” after “The Time Warp”—but too often there’s a surfeit of true wit or even good wisecracks. A late swerve for a note of pseudo-pathos as Frank-N-Furter faces his downfall doesn’t come off in part because his divaish final song is the dullest tune in the film, and besides, who wants to take Frank seriously? His wonderful line, “It’s not easy having a good time—even smiling makes my face ache,” gives the character a signature facet that doesn’t need underlining. Such flailing probably didn’t matter so much on the stage, where the compulsive energy of the performers and the tunes can carry the material along, but the film finally suffers from a lack of a real cinematic invention. Part of this surely stems from the general decision to make the film as a road-show version of the stage production rather than striking out as a genuinely expanded vision. It’s tempting to wonder what a real filmmaker would make of the material. Ken Russell, who had made The Boy Friend (1971) a genuine cornucopia out of the same kind of material, and released Tommy (1975) the same year as Rocky Horror, could perhaps have conjured something really extraordinary. Ditto Fosse or Richard Lester, filmmakers who might have developed a real visual counterpoint to the material’s obsession with movie history. Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974), which the film was paired with on a double bill for a time, lacks Rocky Horror’s hoofer bravado, but far excels it for originality and vigour in filmmaking.

.

.

In this regard, Rocky Horror ran upon a reef that often lies in wait for stage-to-screen adaptations: how far can you go in revising a project before it ceases to be the thing people liked in the first place? Not that the film lacks cinematic values. Cinematographer Peter Suschitsky, who had worked with Kevin Brownlow early in both their careers and would go on to shoot The Empire Strikes Back (1980), gives the film a rich, vivid palette of colour and lensing, one that cranks up the loopy garishness of the material to 11 in places, particularly during Eddie’s madcap terrorisation of the assembled on his motorcycle, and gives the sequence when Brad and Janet approach the castle singing “Over at the Frankenstein Place” a strange, elegiac beauty. But frankly Sharman, whatever his gifts as a stage director and his real hand in creating Rocky Horror as a theatrical entity, was an annoying filmmaker. A couple of years later he tried to film Nobel Prize-winning author Patrick White’s The Night, The Prowler, a story with a not-dissimilar theme to Rocky Horror of a repressed young women being assaulted and finding a certain sick liberation in the experience, but the film is just as leeringly overacted and unsubtle as this one. At least here, overacting and unsubtlety are part of the point. But the superficial energy of the filmmaking and performing can’t ultimately cover up the fact that Rocky Horror loses its mojo badly by the end. Scott’s arrival at the castle sets the scene for some really lame slapstick comedy, with Scott’s wheelchair being attracted up a staircase with a giant magnet and the rebellious guests and flesh toys being zapped with a “Medusa” ray that turns them to stone. The finale is particularly weak and feels like a missed opportunity, as Frank forces his posse of lovers to join in a kick-line chorus in front of the old RKO Radio Pictures logo.

.

.

Here Sharman could have gone nuts and expanded the staging and conceptualism, but settles merely for replaying the stage show’s climax with Rocky going nuts and carrying Frank on his back in a limp King Kong (1933) spoof. In spite of the overt desire to pay tribute to the cheesy glories of classic scifi and horror, Rocky Horror never really gets a chance to engage with them. Maybe it’s because the previous year’s Young Frankenstein had already beat it to the punch on so many jokes. At least there is a gaudy nod to Busby Berkeley as the camera surveys Frank floating in a life ring from the Titanic in a swimming pool with Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” at the bottom. Moreover—and now we’re edging into the realm of pure personal taste here, I admit—Sharman’s work presented a blueprint of freaky style not just to the burgeoning Punk and New Wave scenes (particularly Sue Blane’s costuming), but also to every terrible fringe theatre group and art-pop wanker around for the next two decades, and what was fresh was quickly beaten into the ground; just looking at the chorus line of Transylvanians makes me feel a little stabby as a result. Of course, it’s churlish to critique such a project for a lack of story cohesion or dramatic heft; in fact, the lack of both probably explains the popularity of Rocky Horror, its ultimate rejection of deep meaning as well as the kind of rigour that might have made for a more genuinely funny, tighter experience, which then wouldn’t have allowed the same room for an audience of adherents to write in their own amusement.

.

.

Admirably, too, Rocky Horror never backs down from its joy in transgression even as it tries half-heartedly to locate a deeper meaning. The shots of Frank, Rocky, Columbia, Brad, and Janet exulting in a moment of orgiastic sexuality in the pool weirdly echoes the climax of David Cronenberg’s Shivers, also released that year, purveying a similar sense of the blurred distinction between the elatedly liberated and the genuinely freakish. Frank-N-Furter is soon delivered a comeuppance by Riff Raff and Magenta, two fellow aliens who have been oppressed playing his servants and now take command, but far from being representatives of any controlling order, they’re an incestuous couple who just want Frank’s foot off their necks. Curry’s extravagance, matched to his character, tends to drown out rivals, but just about everyone still brings something great to the table: O’Brien’s bug-eyed, yawing-lipped rock’n’roll face, Quinn’s plummy pseudo-Lugosi accent, Campbell’s look of irritation after falling over at the end of her “Time Warp” tap dance, Bostwick’s shows of facetious charm, and Sarandon right at the beginning of her career, with her big eyes and ditzy-lustful smile suggesting Betty Boop before she reached for the hair dye and went to the dark side. By its end, it must be said, I was left frustrated, even disappointed by Rocky Horror, as its moments of invention, even genius, are balanced by just as many that don’t work or run in circles. Yet I’m still glad I finally watched it, and moreover, I’m glad that it exists, if just for the sake of the fabulous.

Kinda had this musical on my mind, since I just saw a local (good) stage production. Just thought I’d add that there’s a precedent you don’t mention: Whale’s OLD DARK HOUSE. That’s a film which has implied and queer “cred,” not to mention the “unsettling night in a strange house” plot similarity.

LikeLike

Oops: that was supposed to read “imiex libido.” Implied by both Gloria Stuart’s near-naked gown and by Karloff’s resemblance to D.H. Lawrence.

LikeLike

IMPLIED, goddammit! (I seem to be inventing a new language.)

LikeLike

Hi Chris. I’m tempted to comment, re: your strange late night permutations of language, that even Welsh ought not to sound like that.

I do see what you mean, and the similarity to The Old Dark House (and Ulmer’s The Black Cat, which also has the innocent couple encountering building full of weirdos thing) did occur to me. I didn’t think of the facets you present, which are fascinating ideas and definite possibilities. But part of me really wonders if O’Brien really did look at his sources with that kind of depth; one thing that bugged me but which I chose not to saw on about too much in this piece about Rocky Horror was its approach to cinefantastique tropes struck me as rather shallow, a reduction to a funfare sensibility. Perhaps I’m just too touchy as a cinefantastique fan who’s always kind of resented seeing older works in the genre dismissed as trash or camp. I’d think if pressed I’d actually say The Old Dark House does the same idea with better, drier humour and that Rocky Horror could have been seriously strengthened if it had taken some cues from its structure – the levels of the house tethered to the roster of types/characters/sexualities with a sense of layered discovery. As I’ve said, my criticisms really only apply to the film as opposed to the stage version.

LikeLike

Finally catching up with this piece, Rod. Rocky Horror being my favorite film, I was rather wary of what your take might be. I have to say, I think overall your comments are more on point than most of what I’ve read related to this movie over the years. You caught the inspiration BVD provided–in fact Sharman insisted on the entire cast of the original show attending a revival of the film, and told them “You will all see your characters in this movie.” And I love that you catch how well the score functions in relation to the movie’s aesthetic. You’re also right about the influence on punk. In fact, Magenta’s boots in the final scene were purchased at Vivienne Westwood’s Sex.

A couple of points on which I part company from you, I guess essentially interrelated. Like a lot of people who write on the movie, you see the film as losing direction after the seduction of Brad and Janet. But the movie is camp, and camp is exhibitionistic and performative, not introspective or relationship-oriented. So I think it makes perfect sense contextually for the movie to return to a performative structure with the floor show rather than continue introducing the characters to various sexual permutations. This is, after all, a movie where the majority of the characters are omnisexual but the greatest pleasure they experience is doing a dance step number. Similarly, I don’t think the movie recreations and references are structurally off. The movie isn’t a satire, and it isn’t really a parody, but that doesn’t mean such direct recreations of scenarios and sets is misdirected. Like a lot of consciously created camp, there’s an obsessive goal to live within a prefabricated world–the signature line “Don’t Dream It, Be It” (lifted from the old ads for Frederick’s of Hollywood, though nearly everyone in the world missed the referece–yup, including me) being key here. The movie is about living out certain celluloid fantasies, not mocking or derailing them.

Richard O’Brien is a New Zealander, not a Brit, btw.

Still, superb write-up.

LikeLike