.

.

Director: Byron Haskin

By Roderick Heath

It seems now as if H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel The War of the Worlds marked a vital moment not just in the evolution of science fiction as a literary mode, but maybe even of the modern consciousness. Wells contemplated the possibility that life not only might subsist beyond the confines of the Earth, but also might be intelligent and aggressive enough to attempt an invasion, displacing and annihilating humankind, in his tale of the inhabitants of Mars annexing the Earth with great technological advantage only to fall victim not to human ingenuity but to common microscopic infection. Wells was hardly the first writer to contemplate the possibility of alien life, but he ventured deep into speculative realms with both clear and ruthless logic and proper dramatic art, bundling together a panoply of concepts from his scientific learning and intellectual precepts to contemplate with such fervour and detail that it resembled reportage what such an event might feel like and how it might play out. Here was the new creed of scientific understanding reporting dragons on the fringes of its mental maps in the new vision of the Earth not as deistically guaranteed realm, but as mere bauble in the infinity of space, its human populace pretentious zoology. The most frightening reflexes apparent in Wells’ thinking come not from any great leaps of imagination, but from consideration of events still playing out at the time Wells was writing in the processes of colonialism. Wells’ narrator says of the Martians that descend upon Victorian Britain:

“And before we judge them too harshly, we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished bison and the dodo, but upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?”

.

.

You couldn’t ask for a cooler diagnosis of human inhumanity nor more sinister counsel that one day what went around might well come around. Wells also worked a variation on a popular pulp fiction theme of the day, the possibility of an invasion of England by a foreign power, necessitating valiant and gruelling battle in the green fields. This storytelling mode, although the basics have changed greatly over the years, remains the basis of a tremendous amount of popular culture: if the quiet and order of everyday life are disrupted by a destructive force from without, how will we rise to the challenge? But Wells gave it a nasty twist, confronting his then-contemporary readership with the unsettling prospect of an enemy far more powerful and equally careless about things regarded as inferior. In addition to gifting his contemporaries a few chills, too, Wells’ nightmarish tale, realised with force by illustrator Warwick Goble in the original serialised version that appeared in Pearson’s Magazine, bequeathed to subsequent generations a dark and inquisitive strand of science fiction.

.

.

The potency of Wells’ vision has been recapitulated many times ever since. Even if the myth of the event far outstripped reality, Orson Welles certainly managed to burn his name into the mind of an audience for the first time with his legendary 1938 radio adaptation, pinning down the pensive mood of the prewar period with his docudrama conceit that, amongst other things, squarely updated the story with Martian craft landing in New Jersey. Film versions followed Welles’ lead in this. The first cinematic realisation, produced by George Pal and directed by former special effects wizard turned ragged auteur Byron Haskin, encapsulated the mood of the early atomic age. If Pal’s later adaptation of The Time Machine (1960) helped establish the iconography of Steampunk by retaining a delight in an antique vision of technology, The War of the Worlds resists such cutesiness; it remains eternally present-tense, an ideogram representing futurism’s threat. Steven Spielberg’s tilt, fifty years later, became a panoramic meditation on the post-9/11 mood. To a certain extent Spielberg’s take stays truer to the source material, rendered as a bleak and savage travelogue where calamity is glimpsed in dazzling snatches and the nature of the invaders remains tantalisingly vague, creating a maelstrom of destruction from which its human protagonists emerge simply happy to know they’re alive.

.

.

But Pal and Haskin’s version remains unavoidable: no science fiction film of its era is more emblematic. The dense and fleshy colours, ingenious sound design, the vistas of awesome violence and terrible beauty. Which is perhaps why The War of the Worlds still seems like the fount of so much modern scifi on screen, perhaps the most vital between Metropolis (1926) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Most every alien invasion film owes it something of course, up to and including not just Spielberg’s proper variation but also pop remixes like Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day (1996). But the inflection is just as notable in the bold use of colour to create a visual lexicon redolent of the fantastical and otherworldly in subsequent works like Forbidden Planet (1956) and TV’s Star Trek. The haunted, deserted vistas of Forrester’s odyssey through a deserted Los Angeles look forward to a strand of post-apocalyptic cinema, from The World, the Flesh, and the Devil (1958) through to The Omega Man (1972) and even the Mad Max films. The film was to become an obsessive touchstone for several of the Movie Brat generation including Spielberg, Joe Dante, James Cameron, John Carpenter, Paul Verhoeven, and George Lucas, who surely absorbed the lesson that the film’s use of sound to create credulity in the fantastic was as vital as its visuals. Mystery Science Theatre 3000 would name its mad scientist villain after Gene Barry’s hero. Hell, it’s even possible the oncoming styles of car design that fix the 1950s so accurately in the collective memory got some inspiration from the film’s alien death machines.

.

.

The War of the Worlds twists the 1950s’ assertive and chrome-plated flash in upon itself in a pointed parable of jut-jawed heroism suddenly turned impotent, the worst fear of recently victorious and newly-hegemonic America encapsulated when even the omnipotent promise of the atomic bomb is rendered ineffective. The psychic frontiers of the Cold War, that paranoid and strange idealisation of the Communist threat as something lurking beyond frozen reaches looking out with cold intent at the rest of the world, found perfect enshrinement, but so too did the entire mood of the post-WWII world, a world of nerve-tingling oddness, of slippery, arrogant technology and weird new electronic sounds, insinuating their ways into everyone’s lives. The age of “super-science” as Paul Frees’ opening narration calls it was stirring much soul-searching and reflexive anxiety, finding expression in diverse terms, from the demagogic postures of Joe McCarthy to a new fashion for themes of historical empire-wrangling and religious struggle in cinema that played at the same time as a boom in science fiction’s popularity, usually buried in historical epics kicked off the success of Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949). The morality of that new age was still being defined, if indeed it could ever be defined after all in the wake of WWII’s horrors. Little plays of responsibility would be played out in popular filmmaking for most of the decade.

.

.

Close to the start of The War of the Worlds the innocent folk of rural California are seen queuing up to see Samson and Delilah. This seems partly an in-joke, as DeMille had planned a film of the Wells novel in the ’30s, but also a statement of intent, for Pal seemed to harbour ambitions to become DeMille’s successor and knew well his scifi brand had annexed zones of the epic and the mythical DeMille was used to occupying. And The War of the Worlds plays out in the same palette of infernal reds and cleansing blues as DeMille’s later colour films, confirming its similar conceptualism of a Manichaean battle where the Enemy comes on with satanic, overwhelming force only to be finally stalled by “the littlest creatures in God’s creation.” Screenwriter Barré Lyndon had, several years before, helped give shape to the docudrama as a style that influenced a huge number of subsequent films with his script for The House on 92nd Street (1945), and he probably suggested the way this film announces itself, in the blaring terms of a wartime newsreel. Frees’ dramatic intonations recount recent history as a series of brutal wars fought with weapons becoming exponentially stronger, orientating the 1953 audience in terms of immediate cultural reference akin to a modern day film taking a mockumentary approach, and bringing them to the threshold of “the War of the Worlds.”

.

.

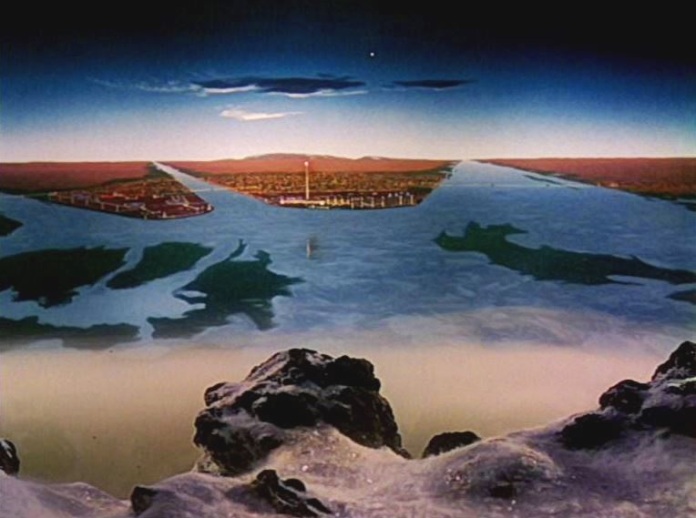

As with Pal’s other productions and much of Haskin’s directorial oeuvre, however, stentorian import and martial clamour are balanced with an insistent edge of the poetic and interludes of quiet intensity working in diastolic alternation. This is immediately apparent in the evocative sequence after the opening credits, surveying the other planets of the solar system from the viewpoint of the mysterious, even unknowable and yet so strangely similar aliens. Sir Cedric Hardwicke’s narration starts off with a slightly tweaked version of Wells’ own writing (“No one would have believed in the middle of the twentieth century that human affairs were being watched keenly and closely…”) whilst also shaded with a planetarium announcer’s recounting of facts about the planets of the Sun such as James Dean would zone out from whilst considering the problems of life here on Earth a couple of years later: he knew the real aliens were parents and new kids in town. Here there remains something of the curiosity and excitement over the possibilities of the universe found in Pal’s game-changing first scifi film Destination Moon (1950), even in the face of things that might destroy us. The film also implicitly, like Wells, notes the commonalities between the Martians, however “vast, cool and unsympathetic” their intellects, and humankind as they behold the choices of the solar system, from roasted Mercury to frozen Pluto, and the planets in between, a range of limited choices for existential action illustrated with delirious colour and wonder. The Martian home world is glimpsed as a hive of super-modern structures amidst flurrying snow and ice, a bastion trying to hold out against climate change and dying resources. The perfection of the green Earth, “eloquent of fertility,” is the inescapable fact for both human and Martian, and so the war of conquest and resistance is fated to start.

.

.

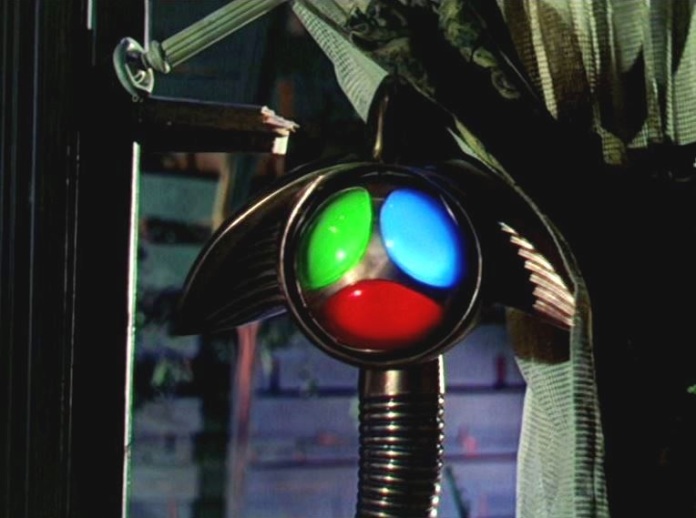

In best Revelation style, a falling star brings Armageddon to Earth, a meteorite scorching its way through the evening sky and crashing in hills near the small California town of Linda Rosa. Volunteers rush to put out the brush fires the fallen colossus starts, whilst a local deputy (Frank Kreig) ventures up into the hills in search of three wise men: scientists from the (fictional) Pacific Institute of Technology up for an r’n’r session of fishing. One of the trio, Dr. Clayton Forrester (Gene Barry), descends to investigate the great space rock, which sits, glowering with heat, stirring dreams of avarice and enlargement in the locals, including one who bashes a shovel against the meteorite, hoping for gold, and others whose ambitions run more reasonably to fast food stands for Sunday driver traffic. Forrester encounters the pillars of the community including local pastor Dr Matthew Collins (Lewis Martin) and his librarian niece Sylvia van Buren (Ann Robinson). But the scientist’s Geiger counter begins to tick as it detects radiation emanating from the meteorite, the devil’s skin of the nuclear age. The early scenes of The War of the Worlds yearn to evoke a version of small-town Americana that’s a touch corny but effective in sketching the petty small-time schemers and white-bread religious leaders and the apple-cheeked librarian who worships the celebrity scientist even if she doesn’t recognise him with glasses on. Forrester gets inexplicably roped into the town’s evening square dance whilst three locals (Bill Phipps, Jack Kruschen, and Paul Birch) watch over the meteorite. Just before packing up and going home, the trio see something begin to move on the hummock, a circular hatchway slowly unscrewing and falling free. A metallic bulb on a flexing stalk emerges, pulsing with power and emitting a creepy ticking sound. The men advance waving a white flag. The response is a blast from a lethal heat ray that leaves behind only man-shaped piles of ash.

.

.

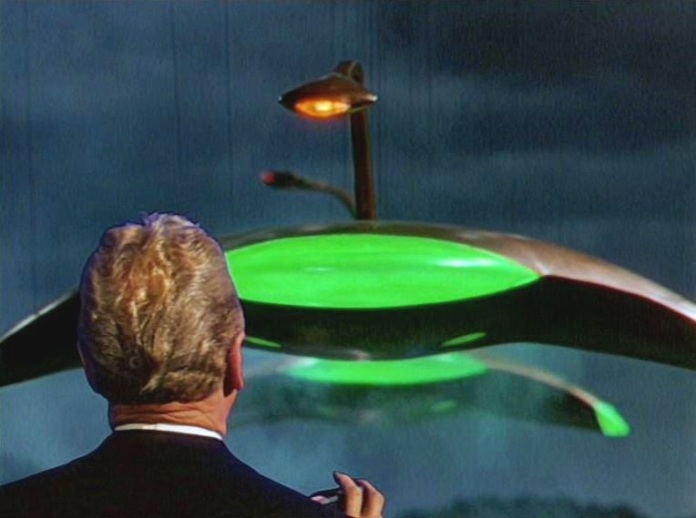

This moment comes straight from the novel, but the touch of the men’s shadows burnt into the ground betrays more immediate news from Hiroshima, nuclear age terror barely concealed by the alien metaphor. The Martian craft remain some of the most singularly memorable creations ever for a scifi film. Here Pal, Haskin, and their production team worked instead to conjure a menace that is graceful, even beautiful, sublimely menacing, all shining, slippery, aerodynamic surfaces, and the baleful, blinking glow of the heat ray that annihilates. The Martian ships are both perfectly technological but also somehow animate with their rattlesnake-like drone, snaking periscope necks, and sweeping, manta ray-like hulls, emitting unnerving pulsing sounds that hint the awful power they soon loose indiscriminately upon the world. Wells’ concept of monstrous tripods is given an update in how they don’t actually fly but instead move along propped up by three invisible beams. The announcement of the Martians’ malevolent intent brings the army rushing to Linda Rosa, under the command of arch-professional soldiers General Mann (Les Tremayne, impressively serious) and Colonel Heffner (Vernon Rich), whilst the eyes of the world on the Californian backwater, including a radio reporter who finds his truck amusingly fried by the heat ray. Forrester remains to advise Mann and scope out the mysterious entities still hidden in the meteorite crater, whilst Sylvia works as a Red Cross volunteer. Her uncle, after encouraging her to stick close to Forrester, resolves to attempt to communicate with the Martians as they finally emerge from the crater with the belief that as an advanced species they must be “nearer to the creator.” Haskin pulls off this sequence with a wicked sense of intensifying rhythm and peril as Collins makes his march out to meet the Martian machines, watched by a frantic Sylvia and the soldiers. The icy punch-line comes as the Martians confirm their lack of familiarity with scripture and scorch the priest off the face of the earth.

.

.

This scene again mimics but also transforms the meaning of a singular episode in the novel, when Wells’ unnamed narrator was trapped with a nervous curate who finally slips into a hysterical fugue and marches out preaching the word into a Martian den, forcing the narrator to kill him. For agnostic Wells religious verve could be dangerous and distracting, for Haskin the transcendental urge is one of openness and communication dashed with appalling enthusiasm by the Other. The pastor’s extermination wrings a furious reaction from the human soldiers, who rain thunder and death down upon the Martians, only to find themselves entirely impotent against the invisible shield the alien machines conjure for protection. Instead the army units are quickly and ruthlessly destroyed by the heat ray and a secondary weapon that simply causes objects to disintegrate on a subatomic level. Forrester convinces the soldiers to give up their defence just before Heffner is killed. Forrester flees in an army plane with Sylvia, only to crash-land in the countryside when flying too low to avoid bombers. The duo trek to an abandoned farmhouse and take time out to recuperate, only for another Martian cylinder to land and careen into the house. Trapped, Forrester and Sylvia find themselves the apparent objects of interest to the aliens, with Forrester just as eager to get a look at them. A camera-like probe surveys the house in search of the couple, and finally one of the aliens, a stalk-limbed, one-eyed thing, comes in and scares the hell out of Sylvia before fleeing with a wild shriek after Forrester throws a lump of wood at it. The two humans just manage to slip out of the house before the aliens annihilate it, and make it back to Los Angeles. Meanwhile the Martian invasion quickly spirals into a rout where the best efforts of all nations fail and populaces flee into the wilds, trying to avoid the aliens that seem determined on their total extermination.

.

.

Of course, The War of the Worlds has retrograde aspects. It might even define some of them to contemporary eyes, in the confident insularity in the portrait of ’50s Americana, the nervous heroine who screams a lot and serves coffee to handsome scientists and stern warriors who roll up all too ready to do battle with the invaders before they know what they are or what they want (“Shooting’s no good!” “It’s always been a good persuader.”) The careful elision of Cold War politics only serves to draw attention to them: many nationalities are mentioned but the Soviet bloc is completely ignored, deepening the suggestion that the Martians are stand-ins for godless, warmongering Commies. With his It Came From Outer Space released the same year, Jack Arnold mimicked the starting point of The War of the Worlds but immediately set about dissembling its clear-cut us-versus-them assumptions in a way that pointed forward the deepening currents of the genre: the aliens become us and the outsider hero is the only bridge. Barry’s Forrester belongs to a school of manly savants that populated ’50s scifi (e.g. Richard Carlson in Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1954, and Rex Reason in This Island Earth, 1955) and has never been seen since, emphasising muscular virtue behind the scientific creed befitting the atom age. Tellingly, Forrester and Mann are supposed to have been previously acquainted working at the nuclear facility Oak Ridge during the Manhattan Project. But Forrester gets to retain his inquisitiveness and his delight in the unknown and wonder at the Martians’ abilities and nature. Costar Bob Cornthwaite had played a similarly curious scientist in The Thing From Another World (1951) who was eventually, explicitly designated a dangerous factor. Forrester represents an ideal of the scientist as humane and conscientious, proactive figure rather than chilly intellectual tool. Barry’s performance is probably at its best when Forrester can’t suppress his boyish excitement as the Martians emerge from the first cylinder even knowing how dangerous they are.

.

.

Haskin also stays true and even exacerbates other aspects of Wells’ vision. Far from offering any real security in the idea of military might, the U.S. forces are even less effective against these Martians than Wells’ imperial soldiers. Forrester’s cool genius is finally left every bit as flailing and helpless as Sylvia’s emotive sensitivity. Even the atom bomb is rendered quaint by the Martian shields, and there is no equivalent to one of the book’s most memorable vignettes, when a British pre-dreadnought successfully takes on a Martian war machine. Interestingly, although grimmer in tone, Spielberg’s remake was ultimately more conventional in this regard, offering a moment when his central protagonist defeats a Martian machine and a finale in which the military regroups usefully. Collins’ death announces a willingness to challenge any parochial notions of moral gravitas in a world that’s suddenly too large and too wild for small-town enforcers of order to handle; in the same year Brando’s Wild One came riding in on his chrome horse to snatch away the daughters of the small Californian town, here the Martians bring an even louder announcement of the age of anxiety. Frees is glimpsed on screen as a reporter wandering through the tumult before the attempted atomic bombing of the Martians, tape recording his account in a clever updating of the epistolary style popular in Victorian genre writing and which Wells mimicked. “These recordings I’m making are for future history,” Frees notes: “If any.” Pal would later utilise Frees again as the voice of the talking rings in The Time Machine who, like the chorus figure he inhabits here, recounts calamity for unknown future ears.

.

.

Haskin had been making films since the silent era, and yet he became, along with Jack Arnold and Ishiro Honda, one of the first directors to become properly identified with science fiction on screen. If producer Pal essentially viewed the genre as a new annex of traditional fantasy and mythic storytelling, Haskin, who became his frequent collaborator, was keen to its textures, able to conjure a sense of the oneiric and limitless sprawl of the unknown. This quality he would reiterate in subsequent works, like the genre-grazing The Naked Jungle (1954), which inverts the sense of scale in alien invasion but remains just as insidious, the fear and trembling in the face of the infinite in the underrated Conquest of Space (1955), the noir-soaked flourishes of his legendary The Outer Limits episode “Demon With a Glass Hand,” and Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), which envisions Defoe’s hero as a man intruding upon the Martian landscape. Haskin’s signature fascination was with the pastoral theme of seemingly diverse characters meeting and communicating in the wilderness, an idea first posited in his first real hit as a director, Treasure Island (1951), and which he’d explore most deeply in Robinson Crusoe on Mars, is certainly apparent here as Forrester and Sylvia find themselves bound together, leading into a quiet interlude in which Sylvia recounts a myth out of her own youth, a time when she hid away in a church and begged for the person who loved her most to find her, which proved to be her uncle.

.

.

This lovely little interlude cuts to the quick of something Haskin repeatedly touches on, the frailty and strength of individual spirit and a search for cosmic requite in the face of overwhelming and inimical forces. This note recurs through all his other work in the genre and some beyond it. In this regard Robinson’s performance, which always aggravated me as a kid – then and now I generally like my heroines of sterner stuff – now seems to me the spirit of The War of the Worlds, which envisions everyone essentially as an orphan looking for their place in the world. Sylvia’s raw humanity is everyone’s, as the film advances to describe a descent into helplessness and chaos in which only a certain effervescent need for succour and the touch of other humans. Forrester’s close encounter with the Martians gives him and his wonderful little cabal of fellow Pacific Tech scientists (whose number includes stalwart character actors Cornthwaite, Sandro Giglio, and Ann Codee) clues as to their physical makeup and suggests the possibility of vulnerability to a biological weapon, an idea that seems humanity’s only recourse once the atomic bomb fails. But the scientists can’t get any project brewing before the Martians assault L.A., so they flee amongst a general evacuation that spirals into chaos, Sylvia driving a school bus loaded with scientists and Forrester following with a truck full of lab equipment.

.

.

But Forrester is dragged from the truck by a mob of men desperate for transport, beaten and left in the street, along with a wretched flimflammer (Ned Glass) who’s found to his horror that money doesn’t mean any to the mob in the street than the vague promise of science to combat the terror. Forrester finds signs that Sylvia’s bus had the same fate, and he begins an increasingly frayed and shambling odyssey around the town as the Martians perform a calculated blitzkrieg to destroy it, following a breadcrumb trail of clues and the memory of Sylvia’s story in searching for her in churches where exhausted, broken, hopeless people give themselves up to prayer and suppliance before fate. The War of the Worlds tried to do a lot with relatively limited resources, evident in the cast populated with lower-order contract players and B-movie stalwarts, depictions of disorder, evacuation, and worldwide calamity that require extras to mill about, and a mid-point montage consisting of stock footage pasted together with a fair amount of invention and given inimitable aid by Hardwicke’s majestic narration. Whenever Hardwicke speaks you never doubt the world is fighting for survival and losing. And yet The War of the Worlds contains more of a sense of moment and grandeur than movies that cost fifty times as much have conjured. Leith Stevens’ excellent score with its plangent strings and sonorous flourishes helps in that regard.

.

.

Moreover, the strength of the film’s imagery is quite remarkable, even if some of the special effects show their age (the very heavy props of the Martian craft required a veritable cat’s cradle of wires to keep aloft, something DVD and Blu-ray prints are especially harsh on). The War of the Worlds is littered with pictures that cut to the essence of science fiction in this mode, often painted in Haskin’s totemic use of red and green as signifiers of infernal destruction and alienness. The pulsing eye of the Martian craft and the flash of its heat-ray shooting at the camera, the three small-town envoys dissolving in its heat. Heffner struck by the death ray, glowing green with his skeleton showing white within before vanishing. Sylvia’s face in strange hues as seen through the alien camera, transformed under an alien gaze into an unfamiliar form of life, just as odd and threatening as the Martians were to her. The Martian’s sucker-tipped fingers clapping on Sylvia’s shoulder and cowering under Forrester’s torch, embodiment of every fear of the murk that shrinks under the light. Forrester’s solitary form, dwarfed and pathetic, wandering amidst a deserted city. The destruction of the L.A. City Hall, a special effects spectacle reused in many films. The final, unexpected pathos of the dying Martian’s arm. Haskin delivers another tremendous crescendo in the final moments as Forrester finally finds Sylvia in a church and rushes to grip her, editing yoking together the moment they embrace, the breaking of a stain-glass window sporting the image of Jesus, and the first sign of the Martians waning and dying, their war machines crashing in the streets outside. By film’s end church steeples are crowding the screen, the act of the Martians destroying the window implicitly signals their sudden striking down by on high in turn, and the film concludes with a chorale of “Amen” even as Hardwicke’s voiceover recounts Wells’ explanation that the Martians have unthinkingly left themselves vulnerable to microbial life.

.

.

The emphasis on religiosity that winds through the film stands in direct opposition to Wells’ pointedly rational vision of biological struggle extended with technological means, but it does give impetus nonetheless to The War of the Worlds as a movie, surveying the unease of the age and wondering what could still be counted certain, amidst a confrontation with Armageddon in terms as fiery and thunderous as anything Biblical. Pal had signalled a similar note at the end of When Worlds Collide (1951) in the prospect of a new Eden. But it became an aspect of Haskin’s work, one that bobs to the surface again in Conquest of Space and Robinson Crusoe on Mars, as intimations of divine intervention save its heroes. By Conquest of Space, though, the sense of religious awe in the universe has become internal and terrifying, causing near-disaster; in Robinson Crusoe, it’s a common value across species in the face of the hostility of the cosmos. A later generation of scifi dramatists would engage the same urge with a different method. For Nigel Kneale and Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky and Spielberg the search for gods was something that could be pursued through the motifs of science fiction itself, rather than offered as a bulwark that could make science fiction coherent and appetising for people just beginning to contemplate existence on a planet where suddenly, after 1945, life suddenly seemed to depend on good breaks rather than good prospect. For all its dated elements, one reason The War of the Worlds still packs the force of legend today is that it enshrined that very feeling forever.

You’ve persuaded me to give the Pal another look. I cut my teeth on Wells’ Scientific Romances — even picked up the bound volumes of Pearson’s with the original run of WotW — but I can’t say I ever really warmed to either of the major screen versions. It didn’t help that whenever this one came around it was always in the same grainy print reframed for TV. And as for the 2005 movie… well, Tom Cruise.

For me the novel is a great period piece, cut from whole cloth, and I’d love to see it given an in-period treatment someday. I don’t know if you’ll be familiar with this VFX reel from a History Channel ‘documentary’ called The Great Martian War, but I do find it pretty much scratches that itch.

LikeLike

You nailed absolutely everything – except my favorite character moment: Forrester tells Sylvia his eyeglasses are only for seeing objects at a distance; he doesn’t need them when he wants to see something up closer. Whereupon, he takes off his spectacles and eyes her intently, with far more than mere scientific interest.

LikeLike

Stephen, I can very much understand your attachment to the book – it’s a favourite of mine too, and Goble’s illustrations for the Pearson’s editions are so evocative they tug at the mind crying for cinematic realisation. But as I said in this piece, I see clearly why it pulls adaptors towards contemporariness: the threat of the hyper-modern is such a deep aspect of the story. Also, the film lover in me demands I stick up for the independent qualities of this and the 2005 version, of which Cruise is only one of many, many aspects.

Steve, I love that moment too, even if it is an epitome of the handsome upright scientist and proto hipster stuff I was mentioning.

LikeLike