.

Director: Joe Wright

By Roderick Heath

On a desolate plain at a forest’s edge, caked in polar snow, an aptly primeval scene unfolds: a fur-clad hunter aims to bring down a reindeer for food. Skewering it with an arrow, the hunter, revealed to be an adolescent girl, says apologetically over the animal’s collapsed, slow-expiring body, “I just missed your heart.” The girl is Hanna (Saoirse Ronan), and with her utterance, the film immediately segues to her name emblazoned on the screen in big Godardian white-on-red letters. Hanna is being raised in a remote cabin in a state of complete removal from a modern world that hovers about the edges of this still-wild and ahistorical zone: when she sees an aircraft fly low overhead, Hanna screams in ecstatic fear.

Hanna’s father, former American-employed German spy Erik Heller (Eric Bana), has trained her in everything from martial arts to speaking dozens of languages, and given her a complete, if purely abstract knowledge of the outside world thanks to reading encyclopaedias to her every night. Slowly, the reasons behind this strange upbringing emerge. Erik is keeping Hanna secret from the world, and specifically, from ferocious CIA bigwig Marissa Wiegler (Cate Blanchett). Erik digs up and presents to Hanna a transmitting device that will, if set in operation, draw American special forces down on them. Because Erik knows that they will have no chance of surviving out there in the world, Hanna’s very first act in the world of modern humans must be to grow up in an instant and undertake Marissa’s murder.

On the face of it, Hanna sounds like a remake of Kick-Ass (2010), divested of comic book satire to concentrate on the dissonant notion of a lethal teenage girl at large in a world completely at odds with her alien perspective. It also represents a jarring U-turn for Joe Wright, in seeming determination to leave behind period and prestige flick affectations. Since Wright culled a surprising gem from the hoariest of source material for his cinematic debut, 2005’s fleet-footed and beguiling Pride and Prejudice, he’s been emerging as a worthy rival for fellow Brit Michael Winterbottom as a metamorphic stylist, suggesting great talent, yet without quite nailing a great film. Atonement (2007), in spite of excellent scenes and casting, struggled to overcome the limitations of its own source material in remoulding litterateur pizzazz as tragic epic, and The Soloist (2009) didn’t find much of the Oscar favour it seemed to court.

The result of this boundary pushing is Wright’s best film to date, a flashy, visually inventive, fiercely controlled and stylised piece of utterly contemporary cinema—even if it does in its way pay tributes to pulp and pop art of the past—amazingly layered and moving at a lightning pace. Hanna doesn’t seek to subvert genre so much as twist it to its own purpose, simultaneously aspiring to evoke mythical mystique, political fable, and gritty action flick with an edge of cinematic freebasing. The eerie, yet warmly intimate qualities of the opening scenes segue into a curious, magic-realist portrait of life on Earth, in which Hanna sees everything imbued with secret beauty and delirious strangeness. Berber washerwomen, camel traders, flamenco artists, clubbing young Euro hipsters, punks, and magicians form a sprawl of humanity who, as seen through Hanna’s eyes, seem genuinely, blessedly peculiar and all the more real because she’s literally seeing them for the first time.

On a basic level, Hanna works similarly to the Jason Bourne series with its super-skilled protagonist keeping a step ahead of the forces of neofascism, and yet it’s closer in some ways to Being There (1979) or Bad Boy Bubby (1991), delighting in its heroine’s complete innocence to all experience,while simultaneously being a deadly weapon who can kill without blinking. Hanna has distinct links to an increasing contemporary strain of pseudo-thriller, using the structure of the globe-trotting actioner to expose the simultaneous fragmentation and openness of the modern world, full of beauties and terrors almost unaware of each other’s existence.

The Godardian pretence of the title card is not unjustified: like the New Wavers in their early work, Wright takes genre material and twists it with visual invention and thematic radicalism. Marissa, ensconced in a citadel of technological imperialism, contrasts the peripatetic world of hippies and good-time teens where Hanna finds herself once she escapes Marissa’s clutches. Erik’s plan was for Hanna to be captured, and when taken to Marissa, kill her before escaping and making her way to a rendezvous in Germany. Hanna pulls this off, but she mistakenly snaps the neck of a decoy (Michelle Dockery) sent into Hanna’s cell as a stand-in for the Texan-accented redhead.

The escape is a feverishly staged sequence in which The Chemical Brothers’ terrific pulsating score infuse Wright’s trippy images, the lighting effects and polymorphic environs reminiscent of the likes of the original The Prisoner TV series, whilst offering strange overscaled sets and wild edits evocative of Orson Welles, an influence which is again suggested in a fight in a shipping terminal reminiscent of Confidential Report (1956), and in the very finale, a death-duel in a rundown amusement park that calls to mind The Lady from Shanghai (1946).

Hanna seems such an unstoppable rogue that one agent lets her shut him in his locker, and she finally, in a moment that evokes the end of THX-1138 (1971), emerges from the secret base to find herself in the midst a Moroccan desert. Hanna’s herculean physicality allows her to flee on the underside of a Hummer, finally finishing up in the middle of nowhere, only to meet garrulous British teen Sophie (Jessica Barden) and her kid brother Miles (Aldo Maland). They’re travelling with their counterculture flame-keeper parents Rachel (Olivia Williams) and Sebastian (Jason Flemyng), on a camping journey, and Hanna sneaks into their van to make the journey across into Spain.

Hanna’s voyage of discovery is imbued with a sense of personal wonder, as Wright brilliantly manages to pack the film with a physical lustre that captures Hanna’s essential naivete, in spite of her fearsome capacities. Hanna is a genuine primitive in the sense that she has all the gifts required for survival and absolutely no sense of the corruption in the human world: she is simultaneously completely open and utterly indestructible. Wright constructs a strikingly orchestrated little scene in which Hanna, who is not familiar with any kind of technology, spends a night in a grotty Moroccan hotel room where all the manifestations of the electricity-run world vibrate with menace and rapture. A boiling electric kettle seems to contain demons, the telephone won’t obey the remote control like the television does, and Hanna, who has been curious about music, having never actually heard it, hears it for the first time on a TV station playing Arabic vibes. She’s used to surviving off the land, and so drinks water from a hotel swimming pool, and stuns her hippie adopters by catching and slapping down before them some freshly skinned rabbits for breakfast. Hanna has carefully memorised personal details for a life she hasn’t lived as taught to her by Erik, which she emits in a ready stream when provoked, but beyond this, she has only a distinctive mix of guileless purity and an honesty so total, even the determinedly alternative Rachel and Sebastian are stunned when she answers Rachel’s question about how her mother died: “three bullets.”

Hanna forms a friendship with Sophie and Miles in spite of the Brit girl’s lippy adolescent sarcasm, venturing out together to a Spanish party with boys, leading to Hanna’s first encounter with a member of the opposite sex. It finishes up with her pummelling him into submission when he’s just about to kiss her. “Should I let him go?” she asks Sophie, who retorts, “As opposed to what?” The stirring erotic edge to life freaks Hanna out right at the point where lips touch, registering the frisson of attraction as electric danger, but later, in a moment reminiscent of the sisterly under-the-covers moments of Pride and Prejudice, she kisses Sophie in an innocent fashion, which nonetheless seems subtly charged with a new awareness of physical proximity and intimacy.

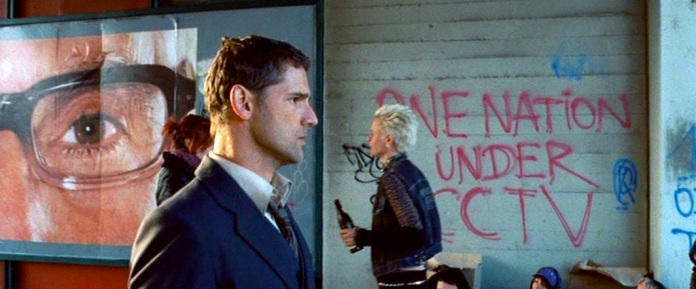

Part of the pleasure of Hanna is that it evokes multiple levels of narrative awareness and texture without belabouring any of it: it’s a road movie, a coming-of-age comedy, a walloping action flick, a psychedelic-tinged satire, an existential fairytale. It’s also impossible to shake its political overtones as a dig at the worst excesses of the War on Terror, as Wright tries to portray the porous nature of the modern world where greatly different cultures are just a few hours’ drive apart, all humming with the same multitudinous vibrancy; the possibility of living “off the map” as Erik has managed undercuts fantasies of total control. At one point, a scrawled graffiti message takes a dig at “One Nation Under CCTV,” calling to mind the agitprop methods of Lindsay Anderson. The story is arguably a parable for how secrecy and violence tend to breed blowback; Hanna is the living embodiment of Marissa’s attempt to get the genie back in the bottle. At the same time, Hanna is clearly never intended to be realistic, taking on a wilfully fantastic quality at points as Hanna defies human limitations; Wright seems to enjoy the sight of the willowy-haired, petite blonde beating the crap out of guys far larger than herself. There’s actually a clever reason for this, as there finally proves to be a science-fiction element to the story: Hanna is not Erik’s daughter at all, but the result of genetic research to produce a superhuman, research Marissa tried to erase, but managing only to kill Erik’s fellow agent Johanna Zadek (Vicky Krieps).

In a touch more definitely reminiscent of John Le Carré, Marissa has to play a risky game trying to stall the CIA, and hires sleazy German nightclub manager and assassin Isaacs (Tom Hollander) because she has to keep her own secrets. Isaacs runs a nightclub/brothel, and he announces to Marissa that his new star dancer has “male and female genitalia,” part of his proud efforts to give people what they want. Hollander must have enjoyed being cast as a nasty bugger with a hands-on approach to violence, as Isaacs and his two goons stalk Hanna from Morocco to Germany, parading around like evil clowns ready to beat and bash information out of the British family. Wright and the screenplay by Seth Lochhead and David Farr make overt references throughout Hanna to Grimm Brothers’ tales (a popular motif in this year’s movies), casting Hanna as an all-action Gretel or Snow White to Marissa’s wicked stepmother/evil witch: the code message that Hanna sends to Erik to confirm she killed Marissa reads, “The witch is dead,” and in the finale, Marissa strides from within the maw of a giant fake wolf’s head. Wright stages one of his now-familiar epic tracking shots when Erik arrives in Germany. Bana strides through a bus station as Marissa’s spooks lurk in readiness to corner him, finally converging on him in an underground car-park where Erik unleashes his tremendous survival skills and bests his attackers in a dazzling blend of showmanship from actors and camera operators, with a little tweaking from the FX guys too.

It’s a little bit disconcerting to see two Aussies—Bana and Blanchett—playing a German and a Texan in an international action thriller. Bana delivers one of his best bits of acting since hitting the big time, a pithy and stripped-back performance evoking his part in Munich (2005), barren of all idealism and hope whilst clinging to steely purpose. Blanchett plays a perfect inversion to her villainess in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), and is at her most menacing and technically impressive in a sequence in which she appears in the apartment of Johanna’s mother (Gudrun Ritter) and carries on a long conversation entirely in German before shooting the old woman in the back of the head with wintry calm. There’s a terrific scene late in the film in which Erik almost corners Marissa in her hotel room: Wright offers a grimly funny and well-framed shot as in the foreground Marissa talks on the phone with Erik, the penny dropping that he’s just outside a moment before his bullets smack through the door and take out her deputy. Marissa, floundering on the floor as Erik riddles the room with bullets and starts kicking the door in, is momentarily huddled in shock with her gun in a recess, before commanding herself, “Move!” and fleeing the room.

But the film belongs to Ronan, whom Wright discovered for Atonement. She pulls off Hanna’s lack of hatefulness even when shooting and cracking bones, whilst mindful that innocence can have a blithe viciousness to it. When Erik finally does battle with Isaacs and his two goons, who resemble rejects from a skinhead oompa band, it happens in a children’s park in the midst of a council estate littered with postindustrial detritus, redolent of modern history’s conflicts reduced to a playground squabble, as the men viciously beat each other to pieces. Marissa performs a coup de grace on Erik, who, answering her bewildered question, “Why now?” replies, “Kids grow up.” The playground motif repeats when Marissa, skewered by an arrow fired her way by Hanna, ends up sliding down a slippery-dip before being put down in an Ourobouros repeat of the opening. Hanna is a product, punishment, and messiah of a new age, and her film could be the most aesthetically and thematically rich thriller of the year.

“The result of this boundary pushing is Wright’s best film to date, a flashy, visually inventive, fiercely controlled and stylised piece of utterly contemporary cinema—even if it does in its way pay tributes to pulp and pop art of the past—amazingly layered and moving at a lightning pace…”

Well, as always you trump the field with the exceeding quality of your writing. What I mean by that is I haven’t seen a better review of this particular film anywhere, and I read quite a few during the time I was wrestling with my unexpected resistence to Wright’s work. The above passage from near the beginning of your review is most exhilarating and persuasive, and it frames economically why you have reached the decision that this is Wright’s best film, a position alas I do not concur with. Neither do I feel that Wright hasn’t yet produced a masterwork. He did indeed cross the finish line in that department with 2007’s exquisite and ravishing ATONEMENT, where he also got a splendid performance from Ms. Ronan. But I won’t go further with that, as this thread isn’t to discuss the virtues and or failings of ATONEMENT, which after all you rightly make scant reference to. My issues with HANNA are that for the most part I found it style over substance, the sci-fic element is underdeveloped, and attempts to fuse this into the main story are heavy-handed. Still I can’t deny Ronan is terrific, Alwin Kuchler’s cinematography and Sarah Greenwood’s set design are striking. I just never felt, despite the potential that Wright connected all the dots.

But again what I think means nothing. What ultimately matters is this is a tremendous piece of writing in glorious defense of its subject.

LikeLike

I’m one of those readers who comes to you for a frame to put around my own thoughts. A bit too undernourished in the vast expanse of film to catch the nuances you always highlight. So when you say “Part of the pleasure of Hanna is that it evokes multiple levels of narrative awareness and texture without belabouring any of it: it’s a road movie, a coming-of-age comedy, a walloping action flick, a psychedelic-tinged satire, an existential fairytale,” you’re providing me the springboard I need to talk about the movie with my friends. If there’s a fee involved for your services, please alert my people.

Hanna, by the way, is my favorite movie of the year so far. Evinced by the fact I willingly saw it three times in the theater with various friends. This in a year filled with movies I’d have gladly walked out of in the middle. And you’ve done it more than justice in your review.

LikeLike

Sam, I’m personally glad they never really stressed the sci-fi element, as that could have gotten distracting or silly – although I’d love to see if Hanna 2 could do something interesting with it. I really have to take issue with characterising it as style of substance – I haven’t seen style work in concert with substance in the thriller genre for several years, and the film manages to condense a lot of meaning into its firm and relentless pace. But we’re agreed on Ronan and that delicious photography. Having watched Atonement a handful of times now, I find it a very good-looking failure that really never finds a way to reconcile its own priorities with its irritating po-mo jaggedness, although that Dunkirk beach scene is a crown jewel of modern cinema. Hanna may indeed be a failure too, in that more could have been done with each of its elements, but at least it has many elements over-brimming with life, but it’s the sort of failure that stimulates me much more than blander one-note successes.

Robert, glad as ever. I’m actually under the firm impression at the moment that this is one of the best years of cinema all told since at least 2007, so we seem to have been watching different movies by and large. But Hanna is indeed lodged firmly in my draft top ten at the moment, along with The Tree of Life and Mysteries of Lisbon and a few others I’m still trying to write up. And it seems like there’s still quite a few goodies to come.

And no, no charge…yet.

LikeLike

Hey, can’t find any contact info on your site – which I’ve just been enjoying. Can you locate mine on http://www.subtitledonline.com and drop me a message please?

LikeLike

I watched “Hanna” just a few nights ago, unfortunately at the end of a long day when I was all tuckered out and barely able to stay awake for it. But even in that state of torpor, I was able to appreciate its audacity and freshness, and to marvel once again at Ronan’s prodigious talent. The scene in the hotel room where she is overwhelmed by the simple technology we would all take for granted is a little masterpiece all in itself.

Your post, Rod, just makes me want to watch it again when I’m fully awake and more predisposed to appreciate it.

LikeLike

We’ve been simpatico of late Pat, which cheers me very much. Oh yes, there’s very rare craft in that hotel room scene.

LikeLike

Drawing a parallel between Hanna to Being There, at once impressive for exemplifying your skills in linking disparate movies across decades and genres, has mostly been supplying me with several days’ worth of enjoyable mental images of Chance running, kicking, flipping, and otherwise occupying a much more quickly edited world. Kudos and thanks!

LikeLike

Now that you mention it, I’ve always wanted to see Peter Sellers playing an action hero – I bet he would have rocked.

LikeLike

Yes! I loved this movie too and wrote a hyperbolically glowing review of it on my blog, but you’ve written a much more comprehensive and accomplished review here.

“The result of this boundary pushing is Wright’s best film to date, a flashy, visually inventive, fiercely controlled and stylised piece of utterly contemporary cinema—even if it does in its way pay tributes to pulp and pop art of the past—amazingly layered and moving at a lightning pace. Hanna doesn’t seek to subvert genre so much as twist it to its own purpose, simultaneously aspiring to evoke mythical mystique, political fable, and gritty action flick with an edge of cinematic freebasing.”

“Part of the pleasure of Hanna is that it evokes multiple levels of narrative awareness and texture without belabouring any of it: it’s a road movie, a coming-of-age comedy, a walloping action flick, a psychedelic-tinged satire, an existential fairytale”

Both of those passages really get to the heart of why I loved the movie so much. I loved it because it was unrelentingly thrilling, fun and entertaining throughout but without losing its edge. Yet part of what made it so thrilling was the way it was so intelligent, how it moved so quickly and seamlessly between settings and emotions and genres. And oh, that Chemical Brothers score! I could watch just about any movie and enjoy it with that score behind it.

I think the film stumbles just a little near the end. Things are a bit rushed, and how the heck does Hanna become a computer expert so quickly? The intelligence and seamless thematic layering breaks down. But the final scene is terrific, and I hardly felt the flaw at all on first viewing. Still my second favorite film of the year so far, after The Tree of Life.

LikeLike

All things considered, StephenM, I agree with you about the latter stages. I would have gladly ridden the wave with Wright and co to let it play out with more precision; one can only presume at least her dad schooled her in the essentials of using Google. And hell yeah, that score. Between this and Daft Punk’s work for Tron Legacy, it’s almost as if smart electronic scores might stand a chance of making a real comeback.

LikeLike

I didn’t read the entire review – I will once I find time to fully invest my in this MASSIVE review (maybe the pictures are making it look longer than it actually is), but just a note on Hanna’s superior computer skills: film’s blu-ray has a deleted scene that explains her new found, astute ability. If included in the editing process no doubt people wouldn’t be concerned for this gap of logic.

LikeLike