Director: Phil Karlson

By Roderick Heath

Phil Karlson is one of those indispensable figures for the enterprising movie fan in search of lost heroes: a jobbing studio hand with a chequered career whose touch, nonetheless, betrays for the attentive a wealth of individuality manifest in scattered gems. Karlson started off with C-grade screen filler in the ’40s, and finished up helming gaudy cult flicks like Ben (1972), Walking Tall (1973), and a couple of Matt Helm movies; in between, he made a run of deeply eccentric and richly textured little noir films, including the belatedly beloved likes of Kansas City Confidential (1952), 99 River Street (1953), 5 Against the House and The Phenix City Story (both 1955). Karlson’s vivid sense of storytelling, with a special feel for moments of intense violence, combined in his best work with a discursive approach to structuring scenes and absorbing character that was rare in the era’s cinema. Karlson anticipates the likes of Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese, the latter of whom has included Karlson in the long list of film influences on him. Karlson’s heroes tended to be cynical proto-hipsters or hard-scrabble, blue-collar guys and girls alienated from their own society, and several of his films dealt with racial persecution and social conflict.

Just as his noir films are joyfully strange, Hell to Eternity, a film based on the life story of Guy Gabaldon, is one I saw once many years ago and could never get out of my head. Revisiting it recently, I realized why: it’s a rowdy, dirty-minded, defiantly deromanticised film that’s a fascinating marker in the era of the decline of the old studios and the oncoming age of a new realism. Karlson’s best films greatly resemble Samuel Fuller’s in taking on meaty subjects with a hard wallop to the metaphorical jaw. Although Karlson ultimately lacked the spiky individualism that irresistibly endeared Fuller to critics and filmmakers even when his career almost entirely foundered, Karlson’s films, often just as bold in their subversion and raw in style, are just as deceptively sophisticated.

This film’s uniqueness is partly disguised by its god-awful title, which tries all too obviously to suggest a melding of the Audie Murphy biopic To Hell and Back (1955) and Fred Zinneman’s From Here to Eternity (1953). Karlson’s film commences during the Depression. Young Guy (Richard Eyer) is a member of a multiracial gang, getting into brawls with the blond Neanderthals in his California schoolyard. Japanese-American schoolteacher Kaz Une (George Shibata), father of Guy’s friend George, is disturbed by Guy’s semi-sadomasochistic displays of bravado and antisocial anger, and drives him home one day to discover he’s been living alone in his house because his gravely ill mother has been hospitalised. Kaz takes Guy to live with him, and Guy swiftly finds unexpected love and unity with the Une clan, including Kaz’s parents (Bob Okazaki and Tsuru Aoki), a couple of harmless, lovable old moths who could have stumbled in directly from an Ozu film. Mother Une begins teaching Guy Japanese, and Guy responds by helping her with her English, a task he’s surprised that none of Kaz’s younger siblings have tried. After his mother dies, Guy becomes a permanent member of the clan and remains virulently aggressive towards anyone turning racist epithets on his family as he matures into the virile form of Jeffrey Hunter. His life reaches a singular and historical crisis point when Guy, as a favor to George (played when grown by an absurdly young George Takei), takes George’s crush Ester (Miiko Taka) out to find out what she thinks of George. When they stop at a fast food joint, insults are thrown her way. Guy assaults the big mouth, only to learn that everyone’s hot under the collar because Pearl Harbor’s just been bombed.

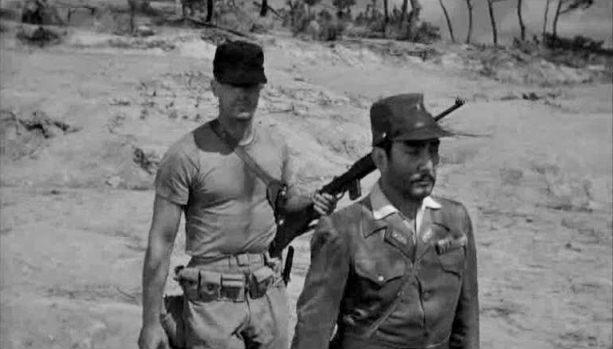

The Unes are soon collectively bustled off to the American internment camps, or, as Guy angrily calls them, concentration camps by another name, in a blunt sequence that concludes with Guy left utterly alone, the bland and friendly suburb he’s grown up turned into a ghost town in the blink of an eye. Ironically, as his family adapts to their exiled circumstances and his brothers are able to join the famous 442nd Regiment, he’s rejected as a 4F. He eddies in frustration and anger at the government until he’s finally inducted into the Marines,because of the desperate need for translators. Guy, never particularly at ease with authority, clashes with raucous Sgt. Bill Hazen (David Janssen) and bests him in a judo match-up, which, of course, cements their subsequent friendship. They’re both attached to a special unit composed largely of skilled, hardened warriors from the Pacific theater being put together for a new campaign, and along with another friend from boot camp, Corp. Pete Lewis (Vic Damone), they raise hell in Honolulu before being shipped out to join in the landings on Saipan, an island colonised and garrisoned by huge numbers of Japanese, and about to become the site of a bloody and protracted death match.

Hell to Eternity bends aspects of Gabaldon’s tale a little: there’s no mention of the fact he was of Latino background, and the actual reason it took him so long to be accepted into the army was because he was still only 17 when he was accepted in 1943. But Gabaldon acted as advisor on the film, and presumably signed off on all that followed. The film fits nominally in with the run of ’50s war movies based on true stories, with their focus on interesting individual experiences of the war, and the sudden onrush of movies about racism and tolerance that began to increase in frequency, urgency, and bluntness throughout the decade. Karlson’s film in that regard is less like the message movies of Stanley Kramer and more reminiscent of the likes of Delmer Daves’ Broken Arrow (1950) and Kings Go Forth (1958), and Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono (1960), in blending the drama with other generic concerns. Karlson doesn’t merely present racial harmony as the only sane option, but fills the film with violently neurotic energy, as the characters are caught between world views and melodramatic crises that expose their conflicts on macrocosmic levels. But Karlson’s film, on another level, couldn’t give a damn about the message aspect of the story, compelled as Karlson really is by Gabaldon as a character, a man filled with anger at his own society and soon filled with it again by the enemy in a war zone, a man whose fractured psyche, informed by his strange, almost Candide-like variety of experiences and outsider perspective on the era, drives him to near nihilism and lunacy before finally turning him into a rare kind of hero. Hunter, an actor of whom I’ve never been greatly fond, gives what is almost certainly his best performance, coherently inhabiting Guy’s emotional extremes.

Most ’50s war films out of Hollywood sadly tended to be rather plastic, best if they stuck strictly to combat. A lot of solid war novels, like Leon Uris’ Battle Cry and Irwin Shaw’s The Young Lions, and other projects that tried to depict not merely raw warfare but the sexual and emotional lives of young men engaged in profound adventures of body and mind hit the screens so bogged down with prestige, prettification, and pandering that they finished up weak and interchangeable. Hell to Eternity is infinitely less self-important, possessed of a gamy vigour and a refreshingly disreputable, gritty, semi-anarchic feel, beyond even what Stanley Kubrick and David Lean then dared put in their war movies. Hell to Eternity instead looks forward, in its cruder way, to the raucous, earthy sensibility of Sam Peckinpah, whose ’60s films, like Major Dundee (1965) and The Wild Bunch (1969), have a similar feel for the overflowing joie de vivre of men who are ironically trapped in lethal situations, as well as the seamy reality of violence. Remember how Bonnie and Clyde (1967) was supposedly the first film to openly defy the Hays Code convention about not showing a gun fired and the person shot in the same frame? Well, Karlson does it here years earlier, and with the same DP, Burnett Guffey, in a sequence that’s amazing for other reasons too. Long before The Wild Bunch, Karlson depicts bursting bullet wounds close up in the midst of a grueling sequence in which Gabaldon, maddened by Hazen’s death, stalks the battlefield flushing out exhausted, wounded, and starving Japanese soldiers and shoots them in the back.

Hell to Eternity is therefore curiously anticipatory and modern in both aspects of technique, and in the tangle of raw violence and ripe sexuality that makes it into the film. Karlson had a peculiar, indulgent interest in simply watching his characters behave on screen, and a particular genius for depicting what I might call the intricacies of homosocial behaviour, or put more simply, guys hanging out. In this attribute, he is reminiscent of Ford and Hawks, but more distinctly modern in tone and attitude, less romanticised. 5 Against The House blended a heist drama not only with portraiture of the psychological damage and social difficulties of former soldiers, but also with a flip and funny collegiate playfulness, especially in its lengthy, discursive opening, that looks forward to the likes of Robert Altman’s MASH (1970) (in fact, 5 Against the House can be described glibly, but with some accuracy as “Animal House goes Rififi.” For its part, Hell to Eternity’s middle sequence in Honolulu offers for no particular reason, except to get some T&A into the tale and to suit Karlson’s taste for an epic, oddball sequence of pure behaviour, the quest of Guy, Hazen, and Lewis to get drunk and laid in roughly that order.

Guy scams a taxi driver out of a load of booze, and, hitting the nightclubs, Guy uses his linguistic skills to hook some Japanese-American B-girls, whilst Hazen points out to Lewis the Mount Everest of conquests, journalist Sheila Lincoln (Patricia Owens), stationed in Honolulu to report on the great enterprise of young men going off to war, and whose ability to brush off the most charming GI lothario has confounded all comers so far. “She writes that everyone should give their all to the enlisted man, but she don’t practice what she preaches!” Hazen murmurs with the ruefulness of one who’s tried. But Sheila does accept an invitation to a party from Lewis, only for the party to prove just a drunken orgy in a hotel room, where another one of the girls the boys have managed to pick up proves to be a former stripper who gives a show, whipping Hazen and Lewis into a frenzy. Sheila, after guzzling liquor with gusto whilst sitting apparently cold and disdainful all night, suddenly arises to do her own striptease, whereupon the males do a fair impression of Tex Avery’s big bad wolf, and Guy finishes up making out with Sheila on the veranda. This whole movement of the film is glorious in its unapologetically discursive, seamy fashion. But Karlson lets it unfold as if it’s really the raison d’être of his film, possibly torn directly from somebody’s memory, maybe Gabaldon’s, maybe Karlson’s, maybe those of screenwriters Ted Sherdeman and Walter Roeber Schmidt—or perhaps they just wished it happened to them. What it clearly does is capture the explosive, incantatory sensual energy of the characters who soon will be venturing into war and the women close to them. It also feels like an attempt to show how the scenes with Frank Sinatra, Monty Clift, and Donna Reed in From Here to Eternity should really have played. In any event, Karlson offers the sexual gamesmanship, frank carnality, and almost blackly comic contrasts of character and situation—with Janssen’s excitement reaching near-lunacy, and Guy, already a practiced seducer, conquering Mount Everest almost casually—with a fearless intensity that lingers long in the mind. Either way, it’s like barely anything in Hollywood cinema between the late silent era and the mid ’60s.

Perhaps such carnality and camaraderie is so emphasised because Hell to Eternity isn’t in any sense a typical war movie celebrating a hero’s competence with violence, but whose gifts for bridging cultures and charming people give him a chance to transcend war. This film is the wicked twin to Sergeant York (1941), revolving as it does around a hero whose heroism is, surprisingly, about saving lives in the midst of carnage and finding unexpected common humanity—except Guy’s not a goody-two-shoes but a man furious with the world, and for whom love and hatred are forever closely related. When the warriors actually hit the beaches of Saipan, the film turns into a grueling, slaughter-clogged slog across country, anticipating Terence Malick’s version of it The Thin Red Line (1998), and in a set-piece sequence in which a band of Japanese defenders, rather than surrender, mass for a banzai charge that engulfs the Americans. Suddenly they’re hurled back into the warfare of centuries past where what hand-to-hand combat skills they have must keep them alive, and the film turns into a Kurosawa movie.

Lewis dies in this battle, and the survivors overlook the aftermath of astounding carnage, ground strewn with corpses. Hazen is killed shortly afterwards by enemy soldiers on the charge, and Guy becomes somewhat unhinged. Where before he had difficulty shooting anyone, he becomes near psychopathic, and where he had used his language skills to talk individual soldiers and pockets of resistance into surrender, he now drops grenades on them and flushes the exhausted and ruined men out to meet his gun. By the end of the ’60s perhaps it wouldn’t be so odd to see a movie protagonist acting in such a fashion, but even then, not usually a hero and a real war hero to boot. It’s revealing then that Gabaldon let himself be portrayed in such a fashion, and it gives force to the feeling, coming on top of the film’s frankness about unfairness of the internment camps and even the dirty playfulness of the Honolulu scenes, that Hell to Eternity is perhaps the most morally complex, honest, and tough-minded American war movie of its era, in its conception of war as a place where any individual can act on both the best and the most bestial impulses within themselves, depending on the pressures in any given moment.

Finally Guy’s CO, Capt. Schwabe (John Larch), tries to intervene, weakly at first (“I’m not saying what you’re doing is wrong, but…”), and then by trying to talk him into resuming his translation work by taking him to watch the spectacle of Japanese civilians hurling themselves off cliffs in obedience to the Emperor: Guy sees his family in the innocents casting themselves to their deaths, and this shocks him out his murderous phase. Finally, he and another soldier locate the underground dugout being used by the Japanese commander, Gen. Matsui (Sessue Hayakawa), and are able to eavesdrop on him ordering his men to stage one last suicide charge. Guy assaults the dugout and takes the general captive, the two men engaging in a duel of wits that, oddly, evokes the deceptions and gamesmanship of the Honolulu scenes, as Matsui, like the reporter, plays coy whilst testing the mettle of his opponent. Guy outsmarts him by not revealing his knowledge of Japanese until Matsui tries to trick him, and Guy finally convinces Matsui to forego the hopeless destruction of the remnant of his army, which, when they go out to see it, proves to be a mass of barely clothed, starving, ruined humans: “God, what a pathetic sight!” Guy says with a mix of disgust, contempt, and pity. Karlson stages an unforgettable climactic shot as Matsui commits seppuku after ordering his men to surrender, sinking to his knees and dying with Guy at his side and the column of his soldiers moving past, barely able to spare their dying commander a nod as they trudge toward the safety Guy has given them. All that’s left is for one of Guy’s fellow soldiers to bestow on him the unofficial title of “Pied Piper of Saipan” as his soldiers see him leading this unlikely exodus.

Karlson made a lot of films that tweaked the Code, and they deserve the description “gritty”. This one was sort of a revisionary war film for the period, along with Richard Fleischer’s earlier “Between Heaven and Hell” ( don’t they love that word ‘hell’?) and a few others, and culminating in Wilde’s “Beach Red” in 1967. Karlson was used to working with second bananas as stars, and got remarkable performances from a lot of his actors. “Hell to Eternity” was a fairly wordy film for a war film – true to life or not, the script was pretty good in this one. Excellent review!

LikeLike

Really great piece. I have to check this movie out. I’ve only become aware of Karlson recently but I’ve long been a fan of a lot of his movies, especially Walking Tall, Kansas City Confidential, and 5 Against the House.

LikeLike

Hi, Vanwall, Dave: Yeah Van, I haven’t caught Beach Red yet but it’s a film that certainly has a powerful cult loyalty for just the reasons you mention. Yep, “Hell” sure was a popular motif. Wilde’s films were really something for their era – see the opening scenes of The Naked Prey. Indeed, Karlson doesn’t just seem to tweak the Code but he outright ignores it sometimes, as in the scenes I discussed in this. Similarly, Kansas City Confidential, which I watched just last week and can concur with about, Dave, is quite amazingly confrontational about the police brutality in the film’s first section, and even if the rest of the film is more prosaic, if still intricately handled by Karlson, it does nonetheless, like this film, feel anticipatory of movies made long afterwards.

LikeLike

I also remember seeing this film in my childhood. It has stuck with me for a long time as well. Thanks for the thoughtful review. I will look this film up and try to watch it again.

LikeLike

TCM has it on today when a lot, a lot of kids will see it as I did and be stunned as was I. Powerful. Unforgettable. Keith Stevens should get an award for the emotional score. Today I weep for our soldiers. God give us a cause! That the Kiyoshis of the world, like the boy in Gabby’s helmet at the end, can live in peace, as in Japan for almost two generations

LikeLike