Mahapurush / Kapurush

Director / Screenwriter: Satyajit Ray

By Roderick Heath

On the international film scene of the mid-Twentieth century, Satyajit Ray represented India in much the same way Ingmar Bergman represented Sweden, Akira Kurosawa Japan, and Federico Fellini Italy. In general perception today Indian cinema is virtually synonymous with the popular ‘Bollywood’ style with its gaudy storytelling, free-form sense of genre, and interpolated song numbers. But there’s been a long tradition of a more traditional dramatic approach in the country’s cinema, and Ray stood for several decades as its preeminent exponent. Ray came from an old and respected Bengali family. His grandfather had been a thinker and the leader of a social and religious movement, whilst his father had been a poet and children’s writer. Young Satyajit would inherit their polymath gifts, and would sustain a career as a writer alongside his more renowned movie career, as well as often writing the scores for his films. Born in Kolkata, then Calcutta, in 1921, Ray lost his father early in life. When he attended university he became interested in art and worked in an English-run advertising firm, and also becoming a designer of book covers, in which capacity he helped put together a children’s’ version of the famed novel Pather Panchali, which would eventually become the basis of his debut feature film.

Ray helped to found the Calcutta Film Society in 1947, and it became a nexus for British and American servicemen and locals to mingle and share their love of movies amidst the fervent and transformative climes of the independence moment, a zeitgeist Ray’s cinema would soon become a major component of. Ray met Jean Renoir when he came to India to shoot The River in 1951 and helped him scout locations. When he was sent to work in London by the advertising firm Ray encountered Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves (1948), and later reported he walked out of the movie theatre determined to become a filmmaker. It took two-and-half-years for Ray and the inexperienced movie crew and amateur cast he put together upon returning to India to film Pather Panchali, mostly through lack of financing. But with some support from John Huston, who hailed a great new talent when Ray showed him an assembled portion of the movie, and a government loan, the film was completed. When released in 1955 it proved an instant and galvanising success, screening for months in its home country, where critics felt it transformed the national cinema, as well as around the world. Pather Panchali also helped introduce the score’s composer Ravi Shankar to international audiences.

Ray’s blend of unvarnished authenticity and humanist intimacy in depicting the hard luck of young hero Apu and his family gave poetic depth to subject matter that might have proved off-putting for many potential viewers in portraying the threadbare genteel pretences of the Brahmin but broke family. Pather Panchali and its follow-ups forming the so-called Apu trilogy, Aparajito (1956) and The World of Apu (1959), still largely dominates appreciation of Ray, one of those compulsory viewing exercises for cineastes. But Ray continued making movies for another forty years, and where the Apu films concentrated on rural poverty and the uneasy march of India into the modern world in a manner that however well-done also suited a certain external view of the country, Ray’s filmography veered off into all sorts of movies, taking on comedy, romance, adventure, children’s films, and magic-realist fantasy, very often struggling with the tension between cosmopolitanism and traditionalism. He also often studied the psychology of people involved in making movies, and those who watch them, with a fretful sense of the relationship between art and life, image and truth, and the incapacity of such anointed people to transcend weakness in offering simulacra of life, studying a matinee idol in The Hero (1966) and a screenwriter in The Coward.

Ray often portrayed characters from the city who travel into the country and in the tradition of the Shakespearean pastoral find their fates taking jarring twists, a sense of connection strengthened by the prominent glimpse of a volume of Shakespeare in The Holy Man, as well as the local literary tradition. Ray remained throughout his career a prolific adapter, with his last film a transposition of Albert Camus’ The Stranger (1991). The Coward and The Holy Man were made as immediate follow-ups to Ray’s Charulata (1964), reportedly his favourite of his own films and generally regarded as a highpoint in his oeuvre. The Coward and The Holy Man are two quite short films, at just over an hour long each, made independently but often exhibited together, their rhyming titles in Bengali helping make them seem well-matched as a diptych of portraits. As films they nonetheless reveal something of the breadth of Ray’s ambitions and talents. Where The Coward is a curt but definite masterpiece portraying frustration, solitude, and heartbreak, The Holy Man is a gently satirical comedy officially making sport of another important facet of Indian life, religion, but really rather examining cultural deference to people who seem to know what they’re talking about, a problem hardly limited to India.

The Holy Man, adapted from a story by Rajshekhar Basu, is generally regarded as lesser Ray and that may be true enough, but it’s a wry and well-made divertissement that stakes out its basic approach in the opening scene: The Holy Man of the title, the so-called Birinchi Baba (Charuprakash Ghosh), is farewelled at a railway station by a crowd of admirers who cheer for him and crowd close. The Babaji tosses chillies to people in the crowd they swear are blessed with healing properties, before sticking out his big toe for people to touch and gain their blessing as the train pulls out of the station. This is a good visual joke that’s also a perfect example of Ray’s economic style, immediately giving the game away as to Birinchi Baba’s lack of sanctity and the tendency to unthinking and slavish devotion turned towards figures like him. Settling in on the train with his perpetually awestruck-looking disciple Kyabla (Rabi Ghosh), the Baba fascinates a man sharing the compartment with him with his ritual of spinning his fingers in counter-rotations and acting as if he’s managed to will the sun into rising. The witnessing man is Gurupada Mitra (Prasad Mukherjee), a prosperous lawyer travelling with his less than credulous-seeming daughter Buchki (Gitali Roy).

Mitra is nonetheless fascinated with the Babaji and soon confesses to him his great pain and confusion following his wife’s death, which have made the former arch pragmatist suddenly spiritually curious. Unwittingly, Mitra has placed himself at the mercy of a man who specialises in hooking people like him, and Mitra soon becomes not only his host but his acolyte too. A little while later, Nibaran (Somen Bose), an intellectual, plays host to his little clique of friends, including his perpetual chess opponent, the insurance agent Paramadha, the money-hungry accountant Nitai (Satya Banerjee), and friend Satta (Satindra Bhattacharya). Nibaran knows about Birinchi Baba’s sway over the Mitra house because he is the lifelong friend of Professor Nani (Santosh Dutta), the husband of Mitra’s eldest daughter. Casually making fun of the Babaji’s supposed divine powers, he tells Nitai about how the Babaji specialises in regressing people back in time to 1914 to let them discover troves of scrap iron left over from the war and make a fortune, only for Nitai to be convinced to try his luck with Birinchi. Satta is much less thrilled by Birinchi’s apparent new home and following, because he’s in love with Buchki, and she seems intent on joining the ranks of Birinchi’s followers along with her father.

Nibaran, a sceptical and distractible hero for the story who proves formidable once roused, feels like an avatar for Ray himself, or rather Ray’s ironic sense of himself as a thinker in a world not always so terribly interested in thinkers, a cigar smoker with his pile of books in many languages and penchant for playing chess, a game Ray himself loved (he’d later make a film called The Chess Masters in 1977), teetering on the fine line between engagement and withdrawal. Nitai spots what is possibly an erotic picture of a woman peeking out from behind a pile of his books, a gently humorous hint of non-intellectual interests furtively lingering behind the learned veneer, but the intrigued Nitai is interrupted before he can reveal the whole picture. When he visits Nani, who has a sideline playing crackpot inventor who’s trying to synthesise a new foodstuff by oxidizing grass, Nibaran becomes increasingly disturbed and appalled when Nani reports to him Birinchi’s absurd pronouncements, and Nani plays a tape recording allowing Nibaran to hear for himself. Birinchi claims to remember all his past lives and has had experiences with great figures through the ages including Jesus, Buddha, and Albert Einstein, whom he claims to have taught the E=mc² equation, as well as being an internationally regarded peacemaker: “He’s solved a lot of problems in Czechoslovakia.” Nani also explains the idea behind Birinchi’s signature finger-twirling habit, symbolising his concept of the present as the mere, perpetual grazing point of past and future. Nibaran is annoyed Nani didn’t stand up for science when listening to the Babaji’s claptrap, but Nani is far too enamoured with any kind of fascinating jargon to critique it.

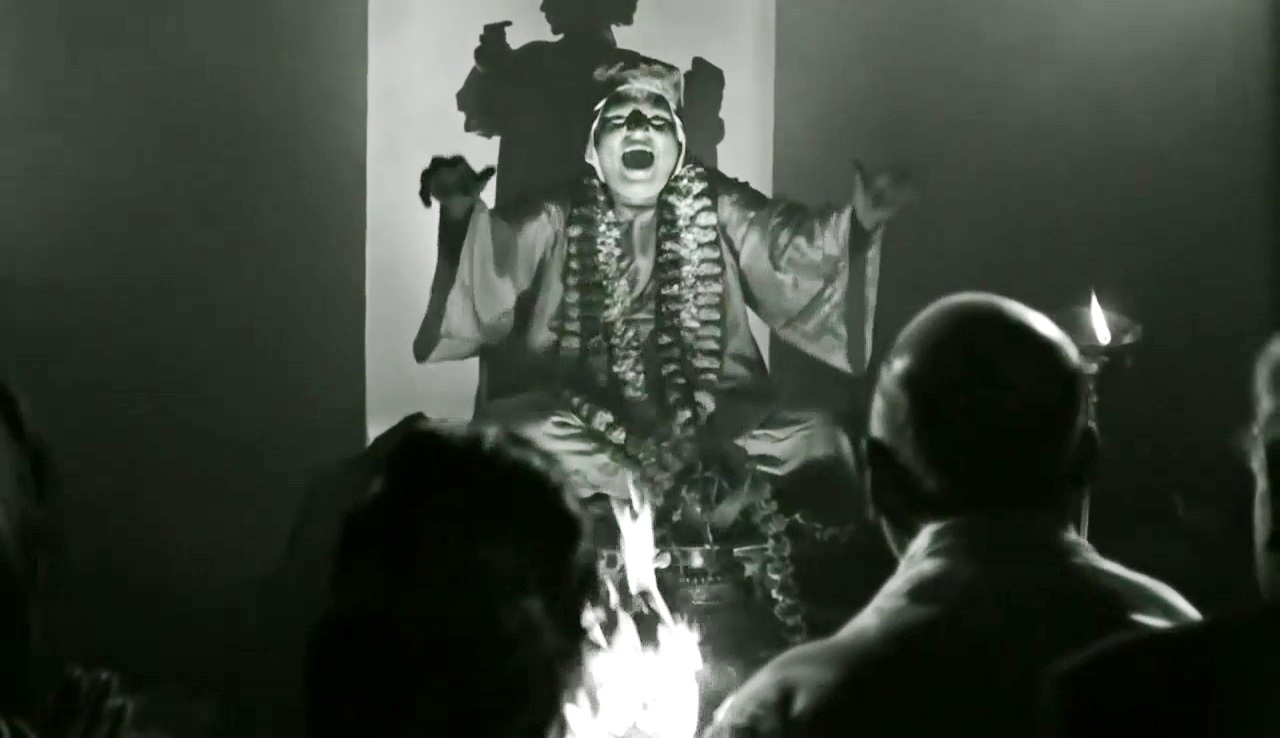

True to the spirit of the Shakespearean pastoral, The Holy Man centres on some good-natured older men trying to help a younger fellow win a girl, in this case Satta and Buchki. The problems of communication between the young lovers echo the integral themes of The Coward, but in a teasing, upbeat fashion. The film’s jests as the expense of the over-educated as well as the gullible and the dishonest skewer the irritable and proud Paramadha, the fuzzy-logic-loving Nani, and Satta, who has attempted to write a marriage proposal to Buchki but his letter was too obscure, filled with bewildering quotations from poets, for her to make sense of. Buchki seems irritated enough with him for such stodgy romancing to make good on plans to become a priestess. Satta is reduced to constantly trying to sneak messages to Buchki, and finally he gets a smuggled note back from her stating she know well that Birinchi is a fraud but cannot defy her father. This aspect of the film, the place of women under patriarchal control, is another connective theme between the two films. Satta reports with good humour to Nibaran after gaining Buchki’s reply, reporting his adventure in sneaking up to the Mitra house to try and deliver one of his notes to Buchki, tossing it to her as she seems to be rapt in one of Birinchi’s mystic rites, in which he waves flaming brands around and seems to invoke a manifestation of Shiva in his holy dancer form Nataraja.

By this point in his career Ray had moved away from the blend of neorealist starkness and flashes of intense poetic visual metaphor – the flock of birds flurrying away at the moment of the death of Apu’s father in Aparajito always leaps to my mind – found in the Apu movies, towards a style more open-flowing and relaxed in engaging his actors and the space around them, expertly using a widescreen format to enable this approach to filming. The Holy Man pauses for a rather French New Wave-like visual joke as Nibaran’s efforts to explain the knot of character relationships with a graphic aid joining pictures of the various cast members including the gormlessly grinning Satta gazing at Bucki’s picture. The influence of Renoir’s cinema is apparent with the architectural integrity to compositions that are nonetheless allowed to form according to behaviour. A perfect example is the introduction shot for Nibaran and his friends, with Nibaran and Paramadha playing chess on a bed with the moaning Nitai sitting at a remove as the apex of a compositional triangle, literally and figuratively interrupting the game. Ray often refuses to cut unless doing so for a specific purpose, and yet there’s nothing dull or static about his work, preferring subtle camera movements to stop his shots becoming rigid. The Holy Man allows a certain level of indulged theatricality to manifest in Bhattacharya and Rabi Ghosh’s performances, the former marvellously, effetely mocking as he explains how he came to “see Brahma,” the latter eddying in boredom and misfiring energy as he wanders about his and his uncle’s rooms, half-naked and partly wearing his costume for playing the manifested Nataraja.

Soumendu Roy’s cinematography on both The Holy Man and The Coward offers a deceptively limpid, deep-focus mise-en-scene that can nonetheless suddenly unveil treasures in careful lighting and camera movement. Particularly fun is the scene where Satta spies on Birinchi’s fire invocation, filmed in expressionistic shadow-and-light-play. Birinchi is transformed into an ogrish vision wielding arcane powers before the appearance of the bogus apparition behind him, a sight that drives Mitra to ecstatics, all background to Satta’s industrious attempts to communicate with Bachki. This scene could well double as a touch of lampooning on Ray’s behalf of horror movie imagery as well as portrayals of eastern mysticism in many Hollywood films. Birinchi’s sermons are comic set-pieces entirely relying on Charuprakash Ghosh’s ability to suggest fatuous delight under a veneer of transcendental bonhomie, declaring when asked about her veracity of Jesus, “People say ‘crucifixion’ – I say ‘crucifact’!”, before swerving suddenly into a show of anguish as he claims to have admonished Jesus for contradictory messages only to feel regret after he was put to death. Asked by another seeker whether the path of urge or the path of satisfaction is the better, Birinchi gives a ridiculously convoluted answer involving ancient sages that eventually winds up justifying consumption because “there can be no satisfaction without consumption.” But he refuses to help Nitai when he makes his appeal, bemused by his request and telling him to spend years master his meditation first.

The Holy Man is often criticised for not being particularly funny, and it generally isn’t in a laugh-out-loud way, more on a level of spry and sardonic sense of flimflam and character as a lodestone for mirth. It’s hard to get across the film’s tone, except to quote a moment like when Nibaran decides to help Satta and resolves to expose the phony sage: “He must be exposed, because if he is not exposed, they will also not be exposed – those who are going and falling at his feet, encouraging him, letting him grow.” Satta replies, immediately fretful at having his clear-cut romantic objective entangled with a quest to reveal truth and exact justice, two things someone Birinchi is an expert at subverting, “You’ve just increased the scope of our work.” When Ray finally offers a glimpse of Birinchi and Kyabla behind the curtain, they’re revealed as a pair of actors who have to live their act, moving like locusts from one feeding ground to another, Birinchi reading H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History to harvest his anecdotal pearls, whilst Kyabla longs to go see a movie. Nibaran is cautious about just how to expose them in his awareness that Birinchi must have formidable memory and improvisational skills to do what he does. Nibaran’s eventual method of exposure involves staging a fake fire during Birinchi’s nightly descent into a supposedly unbreakable divinity-enforced trance, with Nibaran, Satta, and Nitai joining in with the nightly audience at the Babaji’s sermon, teasing the housekeeper acting as doorman with their own little show of uncanny skill and playful promise.

The climactic moments when the fire is started and Nibaran turns out the lights to increase the confusion and panic gains the desired result as Birinchi immediately awakens from his “trance” and cries out: Ray spares an empathetic close-up for the dazed and appalled Mitra. This scene allows a brief burst of loud filmic technique in blending jump cuts and quick zoom shots to create a sense of chaos, with glimpses of the hilarious sight of Kyabla, caught in the middle of applying make-up for his appearance as Nataraja, suddenly dashing through the darkened house with false arms still strapped to his back. Nibaran grabs the abandoned Birinchi by the feet and wiggles them until Birinchi loudly protests, before telling him to get out and not to try plying his act around his district again. Meanwhile Satta takes up Bucki in his arms and carries her out in an act of “rescue.” It seems like a clear-cut victory for the forces of rationality and good as Nibaran and his friends share a smoke and celebrate their success, but Ray appends a final, mirthful sting as Birinchi, glimpsed fleeing the Mitra house over a fence, meets up with Kyabla, who has stolen all the wallets and handbags left behind by fleeing guests, some dangling from his fake hands. “Towards the future,” Kyabla advises, “Let’s go.” Birinchi, with a fleeting expression of fatigue quickly replaced by the resolve of a natural survivor, shuffles away with his nephew.

The Holy Man most obviously connects with Ray’s preoccupation with portraying actors and people who weave fiction for a living. But there’s also a manifestation of interest in the concept of a person with moral and intellectual authority trying to expose chicanery and do people a good they don’t necessarily want done: Nibaran as a protagonist prefigures the embattled truth-teller in Ray’s filming of Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (1989), albeit winning through here because it’s a comedy. The appeal of fiction, of immersion in an alternate reality of potentials, is an ironic zone existing within and alongside of Ray’s realist streak, a zone loaned particular urgency by the problem of India as a place becoming something, a place that must be invented day to day in the course of patching together its manifold cultural reference points and contradictions. Language is unstable in both The Holy Man and The Coward, characters switching seemingly randomly between Bengali and English, tracing out faultlines not merely in education and social sect but also modes of thought and expression, a counterpoint that bespeaks much about the still-lingering impact of colonialism but also grasps a certain assimilating power.

Similarly, having worked on the Apu films where Shankar’s strict classical Indian folk style suited the evocation of a communal past but proved difficult to attach to his images, Ray started composing his own scores blending aspects of western and eastern music to create a more cohesive expressive accompaniment for his films. The spare, jazz-inflected scoring of The Coward helps weave a melancholy mood, just as his more sprightly and traditional-sounding score fits well with The Holy Man. The Coward, whilst occupying a very different space in terms of tone and outlook, is nonetheless similar in the basic precept of its central character, Amitabha Roy (Soumitra Chatterjee), a travelling purveyor of fictions, in his case a screenwriter travelling for research, taken in by a generous host with needs of his own, and contending with over the fate of a woman. Amitabh is travelling rural Bengal and heading for Hashimara where his brother-in-law lives when his car breaks down and is told by the mechanic it will be at least a day before he can fix it. Amitabh accepts the offer of the hospitality of a friendly local tea planter, Bimal Gupta (Haradhan Bandopadhyay), who’s making a phone call from the car mechanic’s office and overhears his predicament.

The Cowards’s opening shot is a sublime example of Ray’s efficiency and simplicity, sustained for over five minutes including the credits, but without any kind of ostentation. Ray simply moves his camera with Amitabh as the mechanic gives him the bad news and then up to the office window, forming a frame within a frame that now includes Gupta as he talks on the phone and Amitabh gets the bad news, and then following the two men as they descend from the office and get into Gupta’s jeep. Gupta is fascinated when Amitabh explains what he does for a living, intrigued by the kind of story he might be writing, but Amitabh isn’t terribly chatty, so the beefy, middle-aged Gupta happily does all the talking. Gupta sets about getting drunk as he hosts Amitabh at dinner and complains about the wearing boredom of being a planter – “It drives you to drink!” – and the limited social circle he’s obliged to keep amongst neighbouring planters, and his general sense of frustration, disdaining Bengali films and claiming that “Bengalis of this present generation have no moral fibre.” He introduces Amitabh to his wife, Karuna (Madhabi Mukherjee), and they have dinner together. Gupta presses Amitabh to drink with him despite Amitabh never having been a drinker: when Karuna asks why he’s insisting, Gupta replies, as if he and Amitabh have entered into some psychic pact involving composing a story, that “the protagonist in his story has his first drink, right?”

The Coward plays to a certain extent like a theatrical chamber piece, Chekhovian in its blend of dramatic simplicity and emotional complexity, but with the interactions of the actors matched throughout to a subtle yet deeply expressive cinematic approach. Consequential details in dialogue fall by the wayside, with Gupta casually mentioning that Karuna said she knew someone named Amitabha Roy in college when he first mentioned the name of their guest, and Karuna’s biting comment that her husband won’t travel to Calcutta or let her do it either despite his complaints about isolation. It’s the camera that tells the real story waiting to manifest: when the trio speak after dinner with Gupta increasingly sozzled, Ray frames him leaning forward in the frame, his puffy face crowding space with a tiger skin on the wall behind like a captured standard from another age, before Ray shifts to a delicate but endlessly consequential medium close-up of Amitabh, the camera performing a dolly shifting focus from Amitabh to the silent, boding-seeming Karuna: the hitherto only vaguely suggested connection between Amitabh and Karuna, the former’s intense and queasy awareness of the latter despite acting the polite guest, and Karuna’s own, evidently curdled disposition are all immediately established.

Later Amitabh confronts Karuna when she shows him to their guest bedroom, protesting that he can’t stand her acting so formally and falsely with him. Soon enough the secret drama is spelt out in a flashback as Amitabh collapses in a self-pitying meditation. Karuna was once Amitabh’s sweetheart, and back when he was struggling she came to him with the news her uncle and guardian wanted to move with her to Patna as he was getting a transfer and also, she suspected, to separate her and Amitabh: Karuna gave Amitabh the chance to marry her then and there, but Amitabh was ambivalent in being put on the spot, and so they separated. That’s the smooth description, anyway, of the complex dance of emotions, crossed wires, and quietly raw drama glimpsed when Ray offers this scene in flashback, unfolding in Amitabh’s squalid little apartment. Amitabh’s sense of inadequacy as a potential provider is exposed as he mentions that he knows Karuna is used to comforts, whilst Karuna’s slow-dawning heartbreak as she realises what she thought was a beautiful leap of faith has been met with ambivalence manifests first as teary intensity and then a calcifying removal that becomes in turn maddening for Amitabh. “My house?” Karuna retorts to Karuna’s statement of scruples: “Did you see the person in it?” The fatal kiss-off when Amitabh asked for more time: “What you really need isn’t more time, but something else.”

The coward of the title is most visibly Amitabh, his failure of nerve before Karuna’s ardent appeal a turn of character that haunts the lives of all three people at the film’s heart, although Gupta never seems entirely cognizant of just why his life is a quagmire he can’t work up the will to escape. Nonetheless the topic of cowardice is woven through the film, from Gupta’s accusation of the lack of “moral fibre” presaging his own confession to being unable and unwilling to disrupt the class barriers bequeathed unto him and his fellow planters by the departed British, to what’s eventually revealed to be Karuna’s method of switching off from reality. Cowardice is a constant aspect of existence, Ray suggests, everyone’s life marked by things they conscientiously ignore, chances untaken, ignorances cultivated, and it’s a state of being that can infect entire populaces, and perhaps not even a bad thing. The choice of making the main character a screenwriter invites a sense of emotional if not literal autobiography, one that resonates on both a metafictional level and a more pragmatic one. As with Bichindi Baba, Amitabh is a professional fantasist, albeit unlike the conman he is gnawed at by his conspicuous compromises.

The Coward gets at something about the lives of creative people, those who don’t yet or won’t ever have the kind of success that opens up worlds, in observing the constant emotional holding pattern they’re obliged to subsist in, where every potential gesture must be weighed for how it will ultimately impact their professional life, and their interior one, that one that always threatens to take over anyway. The Coward complicates the familiar motif of the struggling artist who loses a lover to a rich person who could uncomplicatedly fulfil worldly needs. Whilst more subtly portrayed than the comic characters in The Holy Man, Gupta is like them as carefully captured type, a man struggling in awareness of his blowhard tendencies and the slow sublimation of his better qualities into a cliché as he overindulges drink. Otherwise he’s a charming and solicitous host who even jokingly states that if Amitabh ever stays with them again he can be the one who talks all the time. It’s easy to feel a certain amount of sympathy for him even as Amitabh justifies plotting to win away his wife by only concentrating on his bad traits.

At the same time, The Coward also resembles a fiction composed by Amitabh in his mind, roving the countryside and creating a scenario for their reunion involving coincidences and strange meetings from the threads of private preoccupation. Gupta’s invocation of a kind of conspiracy of accord between him and the writer suggests this aspect, whilst the planter and the writer seem to long after a fashion to live each-other’s lives, whilst his jokey reflection on basic plot patterns – “Boy meets girl, boy gets girl, boy loses girl.” – becomes a nagging leitmotif on repeat in Amitabh’s head. After recalling their last meeting, Amitabh awakens in the middle of the night in a muck sweat, and leaves his bedroom. He finds his way into the Guptas’ living room, a space where filtered light from gently swaying curtains plays on the wall like the ghosts rummaging Amitabh’s mind. Amitabh soon makes appeal to Karuna to abandon her joke of a marriage and run off with him, telling her he still loves her and feels utterly desperate at being thrust back into her company again. But Karuna remains aloof and taciturn, refusing to plainly answer his questions about whether she’s happy or not: “Fall in love again,” she comments whilst strictly brushing her hair: “Am I to blame for that?” She gives a practical remedy for his sleeplessness, loaning him a bottle of her sleeping pills. The next morning, Amitabh receives news that his car still isn’t ready, so Gupta and Karuna drive him to the railway station.

The Coward, whilst articulated with a blend of candour and lightness of touch that’s entirely Ray’s own, suggests Renoir’s influence most keenly, recalling his A Day in the Country (1936) in its brief but concise portrait of romantic disappointment and sense of journeying through both life and physical space. One of Ray’s more interesting formal touches is the way he deploys the flashback vignettes of Amitabh and Karuna’s relationship, starting with the moment of crisis and then later depicting a crucial moment in falling in love, when Amitabh helped out Karuna by buying her a tram ticket back when they were both students: the seeds of the affair’s end are planted when Amitabh jokingly notes it would be a bad thing if she didn’t pay him back: “I study economics – I can’t look at things philosophically like you.” This memory is provoked when Amitabh gazes fixedly at the back of Karuna’s scarf-clad head as he rides with the married couple in the back of their jeep. When he sees her touch Gupta’s shoulder, her finger festooned with a fanciful ring, he recalls one of their dates when he read her palm, an act he admitted he performed purely for the chance to hold her hand.

Karuna admitted she let him do it for the same reason, and Amitabh went off on a tetchy rant spoken by a million young would-be intellectuals decrying timidity and adherence to outmoded mores, speaking of how couples act in England. Karuna irritably decried, “They take it too far!”, but it’s plain that Amitabh’s boldness of thought was part of his great appeal for her, a boldness that in the end failed at its most crucial hurdle. Moreover this sequence helps give depth to Karuna’s reaction to Amitabh’s failing, highlighting the way she’s caught in an odd situation where she wants to escape her anointed role as obedient female without quite having the courage to escape it without the help of a man, Amitabh anointed in her mind as the man who can allow her to both fulfil an expectation to a degree whilst also defying it. Recollection of such moments when things were still possible are the queasy burden Amitabh keeps a lid on whilst play-acting friendliness with Gupta. When Gupta pulls over on a stretch of road passing through a stretch of forest by a river to get water for the radiator, the trio settle down for a picnic. Amitabh gazes in heartsick longing at Karuna as she sits on a rock watching the cascade whilst Gupta asks of the writer, “How’s the story coming along?” “It’s coming,” Amitabh answers with a thoughtful metre. Ray and Roy’s careful use of deep focus with looming foreground elements giving Gupta an imposing quality reveals its purpose as dramatic strategy in one shot as Amitabh looks towards the snoozing man and sees the cigarette burning down in his fingers, knowing he has a very short time to make his move.

Once Gupta falls asleep, he pens a note he tosses in her lap when she won’t look at him, saying he will wait at the train station for her to show up until the last possible second if she wants to leave with him. Amitabh, once finally dropped off at the railway station, waits alone until the sun sets. Chatterjee was Ray’s favourite collaborator having played the adult Apu in the second two films of the trilogy, and he’s crucial to the success of The Coward in the way he plays Amitabh’s suffering here: you can almost feel him eating away at his internal organs in his stewing regret and borderline pathetic admission of need. Ray dissolves from a shot of Amitabh sitting on a bench with face in hands to almost exactly the same pose after nightfall, only for Karuna to march into the frame. Amitabh rises to his feet beaming as he thinks she’s come to leave with him, only for his smile to fade as he registers her stern expression, and she states her purpose in coming, to get her sleeping pills back from him. Karuna’s simple words, stating she needs them and requesting, “Let me have them, darling,” gives a cruelly subtle answer to all of Amitabh’s ponderings: no, she’s not happy and yes she still loves him, but choices were made, and must be lived with. Ray leaves off with a close-up of Amitabh’s utterly gutted expression but with his features blurred and out-of-focus, a startling final note of pain and bewilderment. The Coward is damn near perfect in the economy and incision of emotional blows, and for any other director would count as a crowning achievement.