By Roderick Heath

Jump to Favorite Films of 2022 list

2022 was always going to be a rough year for cinema. Ripple effects of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on production and how movies are consumed were felt all year, setting everything into an uneasy churn. A vast array of strong movies were rudely shuffled off to streaming whilst movie theatres were often left with a drought of big, attention-getting new films to lure people out, and a lot of the big movies that did come out were lacklustre and betrayed the waning grip of recent blockbuster trends. The smaller, quality works that did get release sank without anything to counterprogram against. The only real winner out of it all was Top Gun: Maverick, a vehicle Tom Cruise smartly delayed until it could play to packed and appreciative theatres, and it succeeded in uniting young and old audience members in a single, shared moment. Even if it certainly wasn’t the greatest movie ever made, Top Gun: Maverick proved old-school Hollywood values were the best curative for the doldrums of the moment, especially when the superhero movie is devolving into cluttered and confused pile-ups like Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and Thor: Love and Thunder. And then right at year’s end we got James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water, and just what that will do for mass audience cinema is still playing out.

Things often weren’t that much better in the more officially artistic and serious zones of cinema, with many a movie of strong pedigree and real worth failing to find an audience. It was hard to deny the feeling the brutal financial failure of Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans in particular signalled on some level the fatal decline of Hollywood cinema in its purest form as everything falls into the sinkholes of streaming and a pervasive anti-art mood. Threads of common concern nonetheless wove throughout so many films this year. Spielberg and James Gray, two very different filmmakers, nonetheless both meditated on their most intense childhood experiences through alter egos with many points of similarity. The love of cinema as a shared experience and of media capturing as a mode of tantalising, frustrating meaning bobbed up in works as diverse as Ti West’s X and Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun and Sam Mendes’ Empire of Light. The antiheroic artists of Xavier Giannoli’s Lost Illusions and Todd Field’s Tár surrendered their creativity for the allure of power and self-indulgence, only to eventually be destroyed by the verdict of a society they’ve offended. Terence Davies’ Benediction and West’s Pearl both concluded with powerful but diametrically opposed images of faces, one of cathartic emotional release and the other desperately asserted pleasantness covering bottomless madness and horror. In Pearl and Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling, a woman crushing an egg invoked shattering of a thin membrane of reality and the mental stability of the heroine.

Stark moralistic comeuppances were visited upon the absurd denizens of a landscape of celebrity, influence, technology, and plutocratic riches, played out in isolated locales, in Spiderhead, Glass Onion, The Menu, Death on the Nile, and Poker Face. Spiderhead and Don’t Worry Darling depicted a sinisterly sequestered community ruled by a charismatic creep played by one of Hollywood’s many current Chrises. Films like You Won’t Be Alone, Avatar: The Way of Water, Ted K, Pearl, and Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon grappled with characters dwelling on the fringe of society, wrenched in diverging directions by urges to both completely escape the world and angrily take it on, feeling the temptations of monstrousness whilst also gripped by strange pathos. Rebels around the same outskirts manifested in the likes of Neptune Frost and Prey and Bones and All. Reclaiming youngsters stolen by representatives of invasive and coercive authority preoccupied Rise Roar Revolt and Avatar: The Way of Water. Lovers trapped with each-other in dangerous zones in Stars At Noon, Emily The Criminal, and Bones And All faced the toughest of possible choices, one partner eventually forced to, figuratively and in one case literally, consume the other in the name of survival. Black heroes used to fending off the surreal reflexes of the real world had little fear taking on more fantastical threats in Saloum, Nope, and Day Shift.

Macedonian-Australian director Goran Stolevski emerged with his debut, You Won’t Be Alone, filmed in his ancestral homeland and its language. Stolevski portrayed, in a hazily folk-historical setting, the odyssey of a young woman, raised in isolation and fated to be claimed by a gnarled witch and transformed into her skin-changing, blood-drinking kind, who nonetheless uses her gruesome talents to insinuate her way back into a village community and make human connections. Over the years she tries on different guises, male and female, young and mature, all the while taunted by her justifiably bitter and misanthropic “mother,” who was once burned at the stake. Stolevski’s ambition was notable, his film operating as a work of magic realism mixed with folk horror elements, using fantastical motifs to explore human perversity and gender fluidity. The overall design was similar in concept if not specifics to fellow Aussie director Rolf de Heer’s classic Bad Boy Bubby. You Won’t Be Alone was naggingly intriguing, but also badly hampered by bluntly mannered filmmaking far too imitative of other models, particularly Terrence Malick, and needed a lighter touch. Stolevski shot it in a constant handheld register replete with aggravating close-ups, so what ought to have been dreamy and mysterious was rendered far too literal throughout, working against some of his finer epiphanies of behaviour. Ana Lily Amirpour’s Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon had a similar basic proposition, likewise depicting a supernaturally gifted young woman roaming at large in the world for the first time with a blend of angry bewilderment and yearning, but did so with an entirely different, and ultimately more successful creative palette.

In what could be considered a matched pair with You Won’t Be Alone of mythopoeic meditations on humanity made by Aussies this year, George Miller returned to the big screen with the fantasy romance Three Thousand Years of Longing, an adaptation of a story by A.S. Byatt. Tilda Swinton, wielding an aggravating accent, played a middle-aged expert in storytelling traditions and interpretations who chances upon a glass jug in an Istanbul shop and releases a long-trapped Djinn. The Djinn, after settling down into the sturdy form of Idris Elba, begins narrating how he came to suffer such a fate. Like much of Byatt’s writing, the narrative was pitched as argument, between academic knowing and artistic ardour, intellect and passion, man and woman, with the Djinn’s narratives invoking a sweep of myth-history, great and doomed loves, and metaphorical import, but all faced down by the academic’s forewarned knowledge of how stories like theirs always play out. Miller applied some clever visual touches here and there, and indulged his penchant for bulbous odalisques, and yet the film as a whole felt strangely uninspired. The story never came close to effectively transferring from page to screen, finishing up a loose assemblage of not-terribly-interesting episodes that often looked like outtakes from Alex Proyas’ Gods of Egypt, taped together by the overarching narrative, which aimed for a note of autumnal companionship that was modestly affecting as the miraculous crumbled in the face of the prosaically modern, mostly thanks to Elba’s elegance as a performer: he alone had the power to make you believe in his wise and ageless Djinn.

With Emergency, Carey Williams followed in Jordan Peele’s footsteps in utilising a classic variety of genre film to explore fine gradations of Black American experience. Williams however bypassed Horror to instead tackle frantic ‘80s comedies like Adventures In Babysitting and Weekend At Bernie’s and blended them with a more urgent and serious imperative. Williams offered the adventure of two young Black pals, one nerdy and circumspect and bound for great things, the other a fun-seeking slacker with a streak of socially aware attitude, who find themselves, along with their Latino roomie, stuck with trying to find help for the young, doped-up, possibly dying white girl who turns up inexplicably in their dorm room, without chancing an uncomfortable, even deadly encounter with authority. Williams, with the help of great performances, managed for the most part to walk the line between jaunty shenanigans and something more pensive and biting. The official point about the way being Black intensifies the danger in certain circumstances was sustained, but also dared to venture into contradictory waters, with the heroes wreaking through their choices mounting dramatic hyperbole where the girl’s pursuing friends and the police were entirely justified in their fierce reactions. All ended fairly well but with lingering notes of trauma and regret, which might have been asking just a little too much of what preceded it.

Directing team Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett, who scored a popular success with 2019’s class warfare horror movie Ready Or Not, applied their new-kids-on-the-block touch to a well-worn franchise with Scream, a next generation entry that brought back the classic trio of heroes and other familiar faces but then applied a notably ruthless touch to killing a lot of them off, and positing a new core series protagonist, played by Melissa Barrera, who answers murderous insanity with, well, murderous insanity. The directors turned in a slick and twisty episode spiked with jolts of newly nasty violence and some knowing jabs at precisely the soft reboot approach being applied to the film. The lack of Kevin Williamson’s wry sidelong social and genre commentary and Wes Craven’s dynamic staging, despite the newcomers’ competent mimicry, was cumulatively telling, however, as much of the series’ good-humour and humanity were bled out, along with at least one beloved hero. Whilst it seems to have done the trick of revitalising the franchise box office-wise, I’ll likely sit it out from now on.

Scott Derrickson’s The Black Phone also blended nostalgia and suspense. Set in the 1970s and deploying an anthropological eye not just for the pleasures of being a teen in the era but also its particular, folkloric dangers, The Black Phone depicted a town being terrorised by a serial killer snatching up young teens in his van and murdering them after holding them captive for a short time. The focus fell on a brother and sister, children of a flailing, abusive, grieving father, both of whom prove to share a talent for clairvoyance in different forms. When the boy is taken by the killer and held in a barren basement, his sister tries to use her gifts to track him down, whilst the boy communes with the ghosts of previous victims who push him to try various means of escape. The film generally stole from the best models (including Stephen King and The Silence of the Lambs) and sustained tension to the end. Extraneous elements however, like the kids’ father and the killer’s dork brother obsessed with the kidnappings, proved a real drag, and the period detail tended towards surface fetishism. Whilst the focus on methodical process as the key to survival was engaging, as the young hero assembled tools both physical and mental to defeat his foe, the denouement still felt like a bit of a cheat: we were meant to go “Ah!” when we saw how it all fitted together, and not think about what it really meant for hero’s supposed growth and rebirth as a badass. Ethan Hawke’s flamboyant performance as the creepily masked killer hovered just on the near side of shtick.

Jessica M. Thompson’s The Invitation cast Nathalie Emmanuel in her first major lead role as a young, broke, lonely New Yorker who, after losing her mother and desperate for family connection, tests her DNA and finds she’s connected with a blue-blooded English clan. Flown over the pond to meet them, she falls into flirtation with a criminally handsome and smooth lord of the manor who seems to hold peculiar status over her family and others. Signs begin amassing that something evil is lurking and that her new bae’s true identity is…well, if you don’t guess ten minutes in you’ll have to hand in your horror fan membership. Thompson offered a story with real potential, riffing on the Dracula mystique by combining it with a sceptical variation on Austenesque romance and contemporary cautionary tale that suggested a worse-case-scenario take on Meghan Markle’s journey, blended with shades of Get Out, Thirst, and The Wicker Man. The result, however, was painfully flat: the himbo Dracula was boring, the attempts to invoke feminist and racial angst too paint-by-numbers, the script cowardly in avoiding any truly dark temptation for the heroine, and the con-job romance overextended. The film threatened to become interesting once major reveals arrived at long last, as our heroine was confronted by the cruelty and weirdness of her potential new mate(s), but then pivoted to become a woke superhero origin story, essentially arguing that if you’re well-grounded in online rhetoric evil shalt never tempt thee.

Stunt performer turned director J.J. Perry helmed the Jamie Foxx vehicle Day Shift, a film with a simple but very likeable genre twist for a premise. Foxx played a middle-aged, down-on-his-luck professional separated from his wife and child and trying hard to walk the straight and narrow. With the corollary that his job, under the cover of being a pool cleaner, is actually that of vampire hunter, extremely skilled at overcoming his prey but with a habit of cutting corners that’s made him persona non grata in the small, covert circle of his trade. The film unfolded in a manner reminiscent of ‘80s B-movies, lampooning buddy cop flicks as Foxx was forced to work with Dave Franco’s wimpy bureaucrat. The story wasn’t always tight – Natasha Liu Bordizzo as an enticing neighbour with a secret suddenly became an important character in the film’s last third with minimal set-up, and as with The Invitation the film had confusingly cavalier attitude to dealing with the ramifications of becoming a vampire. Still it was a good lark all told, thanks to Perry’s excellent action directing and fun performances: any film that features Snoop Dog wielding a cowboy hat and a minigun can’t be all bad.

Daniel Espinosa’s Morbius offered yet another vampire variant, this one intended to perform the thankless task of wedging Jared Leto into a superhero paycheque gig, playing a character known as a canonical Spider-Man villain but pitched here as a tragic antihero. Leto played a sickly savant who seeks out the key to perpetual health only to infect himself with blood-drinking tendencies. Matt Smith was his plutocratic benefactor and fellow invalid who proves rather more eager to accept the taint of vampirism. Morbius again had potential. The storyline had echoes of the classical brand of Universal monster movies with their cursed protagonists, with Morbius forced bit by bit to give up his humanity to defend the few things he loves. Whilst Smith’s performance as the former cripple turned robust and eager monster provided flickers of life, the film as a whole was the most tepid variety of current big-budget sludge: released by Sony not long after the colossal success of Spider-Man: No Way Home, Morbius proved an instantly notorious example of lazy, witless franchise extension, executed in the blandest possible style of CGI-heavy and personality-free filmmaking. Leto’s listlessness in the lead didn’t help.

Anthropoid director Sean Ellis returned with The Cursed, a period-piece horror movie that bypassed vampires and went for a werewolf as its monster of choice, or at least an odd, skinny, hairless variation on the concept. Ellis intrigued initially with his glimpse of a surgeon digging a silver bullet out of a soldier killed in World War I, before flashing back a couple of decades to describe the roots of a bloody curse, when a cabal of landed gentry had a tribe of gypsies slaughtered over a land dispute, only for one of their sons to be transformed into a marauding monster to visit punishment on the locale. The Cursed certainly dangled some interesting ideas, operating as a more class and race-conscious variant on classic wolf man motifs and trying to bring an almost novelistic texture to the complex, intergenerational story. But Ellis’s mannered handling conspired to throttle tension and impact with heavy-handedness at every turn, the overtones of dark foreboding and pinched emotion and grating camerawork becoming annoyingly pretentious for what was in the end a pretty straight-laced genre story.

After a few years in the wilderness, once and future indie horror princeling Ti West suddenly roared back to life and attention with two movies in 2022 and with another to round off a trilogy in the offing. His first release was X, a tribute to the aesthetics of low-budget 1970s horror, particularly Tobe Hooper on a visual level, but with a story closer in spirit to oddities like Curtis Harrington’s retro camp studies and Charles B. Pierce’s backwoods bloodletters. West sent a small unit of would-be filmmakers and stars out to a remote farm, sometime in the mid-‘70s, to shoot a porn film, only to find they’ve become targets for the crazed and sleazy attentions of their elderly hosts, a crusty, devoted husband and his murderous, sexually deviant wife. West’s anthropological and cinephiliac obsessions dovetailed as he explored the confluence of transgressive impulses and art in the context of a mythologised era, and hinted at digging out the roots of the current reactionary spirit in the period’s jagged confrontation of liberated youth and jealous age. But for me the film failed to convince on several levels. The uncertain tone wavered between tongue-in-cheek and pathos. West was big on self-consciously gross vignettes but short on real tension and scares. He had Mia Goth play both the young and heedless and old and covetous versions of the star wannabe, playing the latter caked in make-up, a superficially clever touch that nonetheless robbed the film of its necessary evocation of maniacal fire guttering within an aged frame.

A few months later West released Pearl, a prequel to X again featuring Goth, this time playing the previous film’s killer as a young woman in 1918, the daughter of German immigrant farmers subsisting on the family farm in the midst of war and pandemic. Feeling trapped by a domineering and dour mother preoccupied by anti-German sentiment, and obliged to care for her paralysed father whilst her newlywed husband off fighting in France, Pearl becomes increasingly obsessed with becoming a dancer and escaping her lot. Only trouble is she’s also a budding psychopath who likes killing animals to take out her feelings, and as tensions build to a head blood starts to flow. Pearl arguably had a narrative that was a little too obvious, perhaps inevitably given that we already know from X where things are heading: West reportedly threw the project together on a fit of inspiration and filmed it back-to-back with the other film. And yet Pearl proved not just far superior to X but perhaps the highpoint of 2022’s bountiful horror cinema, a weirder, uglier, more impressively and intimately cruel portrait that managed to subvert a certain style of making-of-a-monster story. West forced the audience to empathise with Pearl’s viewpoint even after making clear right off the bat she’s a fruitloop and that her embittered mother is trying to keep a lid on Pearl’s rising madness, and whilst Pearl’s aspirations and emotions are entirely ordinary, her ways of dealing with them are dreadful. West’s newly vivid sense of style found cunning ways to both invoke classic Hollywood products as extrapolations of Pearl’s role in the great American dream of self-invention, whilst forcibly mating them with a bleak genre story that turned the Psycho and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre influence back towards their Geinian roots, whilst also sideswiping The Wizard of Oz with grim sarcasm.

Jordan Peele, now thoroughly ensconced as a pop culture brand, made his third film with the enigmatically marketed Nope, which proved a combined homage to Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind and mixed with plentiful, if nebulous, hints of a parable about racial erasure and media voraciousness at play. The heroes were OJ and Emerald, children of a horse rancher killed in a freakish incident, who try to obtain filmed proof that a huge, UFO-like thing is living near the ranch and consuming horses, whilst their neighbour, a more successful showman with a tragic background as a child actor, seems to be trying to bait the thing into becoming one of his attractions. Daniel Kaluuya was wasted as the rather dull hero, Keke Palmer more engaging as his would-be star sister, and Michael Wincott was the grizzled, famous cinematographer they hire to get a shot of the impossible. Peele proved again that’s he’s a real talent when it comes to setting up mystery and tension, building compelling early sequences with a sense of isolation and paranoia punctuated by the thing’s appearances, as well as a barely connected but suggestive flashback to a bloody, haunting event from the neighbour’s past. But Nope also confirmed some of Peele’s lacks: his hints of deeper meaning were eager to be noticed but weakly tethered to his monster movie plot, and his story and character threads felt underdeveloped. The film as a whole had the tenor of an each-way bet, trying at once to solidify Peel’s status as popular artist telling mass audience stories, and as a biting satirist with an outsider’s voice, but finding the two difficult if not impossible to reconcile.

Similarly driven by characters desperately trying to capture filmed proof of the extraordinary, if in quite a different aesthetic mode, Something In The Dirt saw filmmaking duo Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson wearing many hats, including playing their main characters. These were a pair of alienated Los Angeles men, one gay, divorced, and a member of an apocalyptic church, the other an asexual bohemian and with a string of legal and mental problems in his past. This mismatched duo start working in partnership when they behold a mysterious phenomenon inhabiting their shabby apartment building and determine to document it, whilst chasing an array of clues about its nature down metastasising rabbit holes of esoterica. The mix of elements here was basically the same as Moorhead and Benson’s earlier, defining indie films like Resolution and The Endless, blending realistic study of shambolic individuals with mind-bending high conceptualism and a veneer of post-modern knowing, in what ultimately proves a shaggy dog yarn. But it did expand the filmmakers’ creative palette: the real subject of Something In The Dirt was the nature of creative collaboration, the untrustworthiness of mediated reality, and the way paranoid obsession tends to be refuge and torment simultaneously for many people, the relentless pull to investigate and research in an attempt to contain the world’s craziness. The protagonists were pulled together by a shared sense of wonder and ambition but finally, fatally divided by their divergent characters and worldviews. In this regard, Moorhead and Benson delivered a compelling human story that ended on a haunting note of lingering enigma.

Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling proved an unwitting topic of classically bitchy gossip regarding behind-the-scenes squabbles between director and cast, an ironic fate for a would-be feminist movie that cast a beady eye on hazy nostalgia for the alleged certainties of the 1950s via sci-fi allegory. Florence Pugh and Harry Styles played a couple living an apparently idyllic lifestyle as members of a community employed on a Manhattan Project-like secret enterprise sometime in the ‘50s and run along old-fashioned gender rules. Pugh suffers from an increasing certainty something’s wrong, and eventually learns she’s living in a simulated world created by a retrograde cult headed by Chris Pine’s bromide-spouting Svengali. The story had plenty of familiar elements, with nods to the likes of The Prisoner and The Matrix, as well as ironically owing as much to online erotic fiction derived from The Stepford Wives as the original film, as Wilde engaged with the forbidden thrills of submission and delayed gratification, whilst playing it all as a heightened diary-of-a-mad-housewife story. Wilde confirmed she has a strong eye, backed up by Matthew Labatique’s gorgeous photography, and a good way with actors, particularly apparent in Styles’ surprisingly adroit and calculated turn. But Wilde’s attempt at drip-feeding a feeling of emergent unease exacerbated the way Katie Silberman’s script stretched out the game way too long and didn’t wield that much surprise or satirical bite when it did finally give things away. By the time it did, and offered some intriguing complications to the seemingly prosaic metaphor at the story’s heart, the film had already outworn its welcome, and the plot resolutions proved clumsy.

Zach Cregger, a member of the comedy team The Whitest Kids U’ Know, made his directorial debut in a patent attempt to follow Jordan Peele down the rabbit hole as satirist turned horror maestro. The result, Barbarian, was a surprise hit that tried to mix sidelong social commentary with plain, old-fashioned suspense-mongering and freaky, gross-out thrills. Georgina Campbell was the young woman visiting Detroit for a job interview who finds her far-flung AirBnB double booked, and so must share it with Bill Skarsgard’s intense nice guy, with the pair soon confronted by signs they’re far from the only ones sharing the house. Justin Long was tossed into the mix mid-movie as the mystery house’s owner, a sitcom actor accused of rape who decides to sell the property to pay his legal bills, only to also be drawn into the unfolding mayhem. Barbarian started well, with its believably tense and provocative situation and introduction of dank, alarming yet also enticing enigma that bends the characters out of their rational minds, even if Skarsgard tried a little too hard to work his character’s ambiguity. Cregger evinced a strong sense of style. As it played out though, the story turned out to be extremely familiar stuff, with its lumbering monster crone offered as the by-product of generations of diseased abuse, with a weak last-minute stab at investing it with pathos but otherwise simply serving as a standard movie monster, with added attempts to encompass fashionable talking points barely connected to what’s actually going on. Cregger’s desire to keep his ultimate game vague resulted in some ostentatious storytelling shifts in focus and style that had superficial impact but felt forced, and would probably have worked better if deployed in a more classical fashion. By the end the film collapsed in a heap.

Neil Marshall’s The Lair had many of the same touchstones as other genre films of the year, with loud nods to John Carpenter and James Cameron, as well as the glorious old school of creature feature, the kind that sported monster costumes that don’t quite fit properly around the crotch. It also announced Marshall’s determination to get back to his roots circa Dog Soldiers and The Descent. His wife and screenwriting collaborator Charlotte Kirk starred as a badass pilot shot down over Afghanistan in 2017, who discovers an old Soviet bunker inhabited by grotesque chimeric beings. Barely escaping whilst the critters rip apart some hapless Taliban, she takes refuge at a US Rangers outpost, only to suffer siege by the tough and toothy blighters. The Lair lacked the cleverness and deftness of characterisation Marshall once imbued on Dog Soldiers, the acting from an unseasoned cast often broad and awkward, and the last act got a little too frenetic and indebted to Aliens for its own good. And yet, whilst less polished than the likes of Nope or Barbarian, ultimately I found it a more successful film, an enjoyable, pure-hearted tribute to, and example of, the B-movie ethos. That’s largely because Marshall’s craftsmanship and capacity for tackling monster movie thrills with authentic relish proved undimmed. The film also provided a curiously salutary revisit to the director’s penchant for political parable as explored in Centurion, with overt nods to Zulu and the theme of empires fleeing inhospitable lands.

Colin Trevorrow’s return to helming the Jurassic Park franchise with Jurassic World: Dominion was a more straightforward special effects-driven monster movie than Nope, albeit one that also tried a little to shake up the material a little, with dinosaurs now roaming the world at large, fuelling the rise of exploitative black markets. Heroes new and old were pitched in together to battle yet another nefarious plutocrat, this time played by Campbell Scott and supposed to be the same one who caused all the ruckus in the original film, when his attempts at genetically engineering market advantage result in swarms of mutant locusts wreaking havoc. Dominion had real problems, including some jagged editing that hinted at last-minute interference, and some extremely tired plotting, particularly in the downright perverse subplot involving young Maisie Lockwood and her girlboss genius mother-twin, a particularly egregious example of trying to reorientate narratives to be more female-centric in the silliest manner possible. The film was still better than generally painted: the united cast of old favourites and new fixtures interacted well, Trevorrow had fun giving them all a moment to shine, and the action sequences were strong, particularly the wild mid-film chase sequence in Malta.

Parker Finn’s Smile, the year’s biggest Horror hit, like Barbarian prioritised raw creepiness and menacing thrills staged with cinematic largesse over pretentions to deep commentary and parable, although it still built itself around a blatant metaphor for the insidious power of trauma. Sosie Bacon was the dedicated but vulnerable psychiatrist who, after seeing a panicky patient kill herself whilst wearing a hideous fixed grin, finds herself dogged by a malevolent trickster demon that makes clear it intends her destruction in the same way, and her attempts to escape the curse mean confronting the life-defining imprint of her mother’s suicide. Finn’s film was initially intriguing and gained much from Bacon’s impressive, likely star-making performance, even if she was pushed to inhabit extremes of neurosis with near-comical speed. As a whole though I found Smile didn’t add up to much, in part because Finn’s direction was so showy and spectacle-driven that it kept giving the game away, where the story needed a more brittle and deceptively calm setting. Interludes of showy gore and demonic manifestations were overdone, and by the time of the nasty bummer climax, the heroine’s pathos had been outmatched by genre shtick and bumper sticker psychology.

Scott Mann’s Fall exemplified several recent trends in attention-grabbing action-thrillers – just thrust one or two comely young women into a high-pressure survival situation, throw in some grief, trauma, or other just-add-water feels as an identification pretext, and away you go. In this instance, the heroines were two young devotees to the religion of extreme sports, but with one, Becky, turned apostate since her husband died in a rock climbing accident. The other girl, Shiloh, now a rising social media star, is determined to shake her pal out of her grieving torpor, and convinces Becky to join her in climbing a colossally tall, soon-to-be-demolished TV antenna tower in a desolate stretch of the American west, only to find themselves trapped atop it. In order to happen the film depended on the two women being astonishingly reckless and foolish, and the script took refuge in some now-cornball clichés, including a particularly silly narrative fake-out and shock reveal, and liberal pinching from Neil Marshall’s The Descent. Still, Fall remained engaging almost until the end, thanks to glimmerings of a nicely vicious lampoon on influencers spouting pop no-fear bromides, and providing thrills aplenty, as a calling card for Mann that proved him capable of sustaining a sweat-inducing sense of danger in a tightly focused setting.

Baltasar Kormakur’s Beast was almost the same movie, albeit with a different subgenre frame. This time the protagonist was Nate Samuels (Idris Elba) a recently widowed doctor on a visit to his late wife’s home village out in the South African veldt whilst trying to reconnect with his estranged teenage daughters. Attacked by a lion that’s been driven to indiscriminating, homicidal fury by poachers, and left stranded in a rugged stretch of a remote national parkland, Nate was obliged to protect his daughters and try to save his wife’s childhood friend and game warden Martin (Sharlto Copley) from both the murderous animal and the well-armed poachers. The script was, again, just a little too basic and eager to deploy its pretexts before getting down to business, and the lion itself – animated with surprisingly convincing CGI – was presented at some points as an improbably cunning and irresistible force and at others as something a bit more realistic. The strength of the lead actors and Kormakur’s staging, complete with constantly prowling, paranoid camerawork, made it a decent, entertaining survival thriller. Also nice to see Elba playing an everyman type of hero, albeit one who when push comes to shove can still wrestle a lion.

Sam Walker’s The Seed provided an intersection for at least three of this year’s movie strands, blending satire on pushy, queen-bee influencer culture, portraits of young women suffering millennial ennui, and chamber-piece sci-fi-horror. Walker depicted three friends who retreat to a house in the California desert for one girl’s self-promoting fashion shoot, with tensions manifesting in their diverging outlooks even before a meteor shower deposits a disgusting, turtle-like alien life-form in the yard. The creature soon begins asserting an insidious sway over two of the women, infesting their bodies with alien spawn, leaving the third to face some terrible choices. The Seed’s low budget was telling in places, the acting a bit forced, the script dotted with unanswered questions, and the regulation final girl a bit pallid. Still, Walker managed to do quite a bit with not much, applying flecks of very dark humour to visions of icky assimilation and body horror touched with aspects of kinky sexuality, as the alien played at becoming a mind-and-body-melting extra-terrestrial Hugh Hefner.

Speaking of body horror, the style’s progenitor David Cronenberg re-emerged with Crimes of the Future, a film that recycled the title of his 1970 short film attached to quite a different story. This variant was set in an epoch where both physical pain and infection have vanished from the human experience, whilst some people suffer bewildering growth of seemingly extraneous organs, and so self-mutilation is the new art. Cronenberg offered a sardonic self-portrait via Viggo Mortensen playing Saul Tenser, who wows the art scene by making spectacles of getting his aberrant organs removed. The film didn’t so much have a story as recount Saul’s interactions with various scenesters, bureaucrats, militants, and cultists, eventually confronting the possibility that the human race is evolving to live off its own plastic waste. Cronenberg certainly hasn’t mellowed when it comes to drumming up intriguing ideas or ugly-beautiful images, but like quite a few of his late career works it really just kind of sat there on a dramatic level, filled with elements that went nowhere and dotted with clumsily blunt violence, both a portrait and example of an intellectual-artist’s tendency to hide from emotional intensity by taking refuge in conceptualism.

Mark Mylod’s The Menu also took on the uneasy relationship of artist and audience and laced it with flashes of outright horror and blackly comic meditation on one of the year’s most popular themes, in brutally accosting the rich and influential. Ralph Fiennes was Chef Slowik, a titanic figure of the culinary world who invites a select coterie of smug-uglies to his cutting-edge restaurant on an island and treats them to the products of his cult-like operation, only to slowly unveil an intention to kill everyone by night’s end in a banquet of truth and death. Anya Taylor-Joy was the humble escort accompanying one guest, who finds herself doomed along with everyone else unless she can find the chef’s one weak spot. The Menu was engaging on a baseline thriller level although it spurned believability in favour of a kind of nightmare logic that might have been aiming for the Buñuelian but came closer to Grand Guignol camp like Theatre of Blood (1972). The Menu was packed with concerns of potential, particularly in exploiting the curious grip celebrity chefs have on the contemporary bourgeois mind, testing the eternal tension between creative figure, critic, and consumer, indicting the naked classism often lurking behind foodie culture, and considering the mix of sadism and masochism often required by success on the highest level. Like too many films to tread such territory this year, however, the satire (in a script by two former The Onion scribes) was tinny and shallow, sacrificing any nuance or clash of voices to better have its basic, populist thesis, and indulging its elegantly deranged tormentor-avenger to a disturbing degree. The programmatic nature of the story meant no real surprises were in store, which meant that once the punchline arrived, The Menu added up to little more than a sick joke with a self-congratulatory Hollywood player point, in arguing hamburgers for the masses are superior to fine dining for the discerning.

Graham Moore’s The Outfit was another thriller that sought to make minimalist virtues out of production lacks, if in a more intimate and restrained manner. Filmed on a single set, The Outfit’s title was a pun hinting at two aspects of the story, which unfolds entirely within a Chicago bespoke tailoring shop in the 1950s, run by an aging, prudent-seeming English immigrant, Burling (Mark Rylance) with the help of a young protégé (Zoey Deutch). Burling is connected with a big-time gangster who uses his shop as a message drop as well as a source of good clothes. Deutch is playing dangerous games, a gang war seems about to break out, the modest tailor – sorry; cutter – is hiding his own motives, and things come to a head when the gang lord’s son brings a wounded pal there to hide out, forcing secret loyalties to emerge. The Outfit certainly reiterated how a filmmaker can tell a good, gripping story with a couple of rooms and some good actors. As a whole though I found the film a bit facetious, with twists and confrontations piling up to a rather absurd degree, which combined with the cramped setting left it all seeming just that little bit too theatrical and artificial, if still diverting.

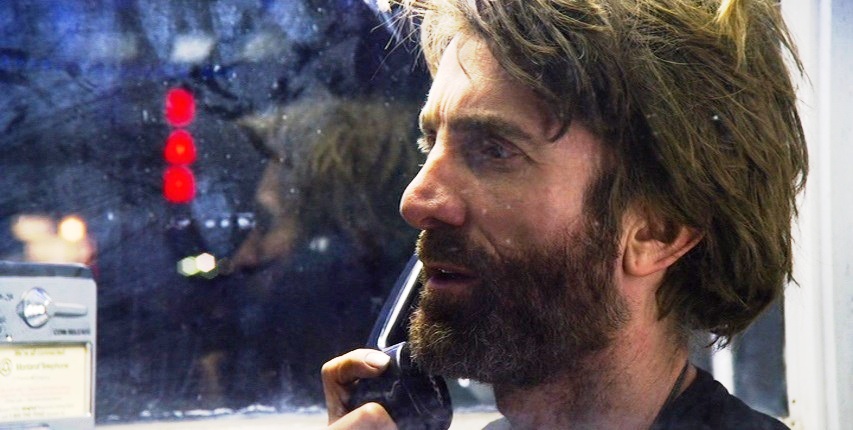

Michael Bay’s Ambulance once again revolved around the basic concept of dangerous criminals crammed into a tight locale, if articulated in the exact opposite manner. Bay applied all his formidable technical skill to his remake of a Danish film, which saw two brothers, played by Yahya Abdul-Mateen and Jake Gyllenhaal, both raised by a criminal father, staging a bank robbery in downtown LA with very different motives in mind. Their getaway proves disastrous and the duo finish up holding two ambulance medics hostage in their vehicle and careening around LA at speed, looking for any chance to slip the net. The film wedded fraternal melodrama as old as the movies themselves with frantic, absurdist humour and dashing action staging, with Bay making plentiful use of swooping drone shots in the midst of staged chaos. Ambulance saw Bay trying to stay on the cutting edge of Hollywood tech and style whilst also growing just a little out of his perma-‘90s dudebro bliss zone, and Gyllenhaal and Eíza Gonzalez as one of the paramedics gave smart performances. Trouble was, Bay kept spoiling the impact of the dynamic camerawork with his usual incessant and careless cutting, and the overheated dramatics became more exhausting than compelling by the climax.

Special effects maestro Phil Tippet emerged from his back shed with a movie project over thirty years in the making – the stop-motion epic Mad God. This labour of love was a frequently grotesque and surreal vision of a post-apocalyptic future landscape, inhabited by labouring homunculi, misshapen monsters, mad doctors, and warring magicians. As a technical achievement it was practically without equal, and as an aesthetic one undeniably powerful, its rank, ugly, often despairing mood quite palpable but leavened ever so slightly by humour so dark it might count as a black hole. How much it worked however depended on tolerance for the constant stream of hyperbolic violence and sadism, and the opaqueness of its suggested parable, which seemed to want to say something about the cycles of war and environmental degradation but was ultimately more enthralled by its own whacko stream of invention. At its best it was genuinely, peculiarly transfixing as a portrait of a total state of lunacy; at its least it resembled the drawings a particularly talented, morbidly creative teenager might sketch inside their math book cover. Cult status certainly awaits.

10 Cloverfield Lane director Dan Trachtenberg made a bold grasp at one of the seemingly poisoned chalices of current franchise cinema, expanding the Predator mythos with Prey. Trachetenberg offered a wisely bold twist in trying to revive the series by shifting to a period setting and deploying a what-if scenario. Prey depicted a young Comanche woman (Amber Midthunder) in the early 1700s who, determined to become one of her tribe’s hunters, ventures out alone into the forest where she encounters both boorish French trappers and something far more dangerous and mysterious. This set-up allowed Trachtenberg to get back to basics in again telling the story of one wily hero who eventually has to take down the alien with smarts and guts, with a new, added gloss of trendy politics with girl power and indigenous perspective exalted. The film was superficially well-executed, with Trachtenberg’s dynamic staging and minimalist special effects matched to determination to tell a familiar story well and patiently, even if failed to offer a convincing-feeling depiction of the Comanche lifestyle, with Midthunder’s performance too calculated as an easily assimilated emblem for millennials.

Chloe Okuno’s Watcher cast Maika Monroe as the flailing former actress wife of a young businessman assigned to work in his company’s Bucharest office. Left alone in their sleek, barren apartment during the day and often into the night, and with dread stories of a serial killer at large and few people she can communicate with, she becomes convinced a man in the opposite building is watching her with evil intent, but can’t convince anyone her concerns are urgent. The basic story here was well-worn, very similar for instance to John Carpenter’s Someone’s Watching Me!, but sought to highlight an implicit feminist theme about being listened to and believed. In those terms Watcher was a little thin, as the script never quite engaged with its characters beyond the obvious – the husband for instance was a rhetorical stick figure – and Burn Gorman was a little too obviously if effectively cast as the inscrutable onlooker. Okuno compensated with a slowly, steadily woven sense of dread and alienation, with a strong feel for the location. Monroe portrayed the heroine struggling to climb out a mire of weak-willed isolation with real class, and built to a properly agonising climax.

Steven Soderbergh’s Kimi was a film with similar precepts to Watcher, likewise depicting a young woman – Zoë Kravitz this time – living an isolated life in a to-die-for apartment and with at least one man spying on her. This time, however, the heroine’s solitude was by choice: stricken with agoraphobia after being molested in her last job, she now works remotely for a rising tech firm, analysing recordings of users of their Alexa-like AI system. When she hears what sounds awfully like a murder being committed, she begins digging to find the truth of it, only to find the trail leading to her employer. Soon she faces not just corporate obfuscation but Orwellian surveillance and hired killers on her tail. But they don’t reckon with either her grit orher intimate knowledge of the tech they propose to corner her with. Following No Sudden Move, one of his most annoying movies, with Kimi, one of his best, reiterated that Soderbergh is by far and away at his best in pulp entertainer mode, trying to invisibly blend thrills with strong elements of social critique. The result was glib in places and cried out for more interest in its perverse marginalia, like the lonely peeping tom who proves to be a nice guy but is only used as a kind of deus ex machina, which some of the film’s influences like Hitchcock and De Palma would have wrung for ripe humanity, as indeed the Soderbergh who once made Sex, Lies and Videotape might have done. That said, Soderbergh worked his most chicly efficient filmmaking to date. Kravitz, as the blowsy, damaged, but wily and quietly badass heroine, gave a strong performance which when viewed as a companion piece to her Catwoman in The Batman felt close to defining a contemporary archetype.

Andrew Gaynord’s All My Friends Hate Me applied a mordant, unpredictable tenor to a study in social and psychological tension by playing it out as a blend of black comedy and folk horror creepiness. Gaynor depicted a former party animal reunited with his posher pals from university over the course of a weekend bash to celebrate his birthday and recent engagement, only to find himself feeling increasingly unmoored and paranoid when he just can’t recapture the old wild spirit. To the extent that the movie eventually proved an elaborate miscue of style it couldn’t escape a cumulative feeling of being excessively arch, and it ultimately shied away from the intriguing depths of character and consequence it wanted to evoke, leaving it to some extent as merely a variation on a particular brand of very British comedy-of-humiliation more often seen on TV. It was nonetheless clever in keeping the exact truth of what’s going on hazy and charged with an off-kilter blend of dread and bitter humour, until the climactic revelations that proved in essence to be another shaggy dog story, but also dared ask a genuinely needling question: what if you’re the worst person you know?

Swiss Army Man auteurs Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert returned with their own particular, more frenetic brand of metaphor-heavy, reality-twisting, post-genre mischief applied to what was actually a minor-key character portrait, exhibited in their art-house hit Everything Everywhere All At Once. Kwan and Scheinert’s film was the tale of a middle-aged Chinese-American Laundromat owner who, faced with multiple personal and business crises being brought to a head by an ornery IRS agent, finds herself plunged into a multiverse-spanning quest connecting her with myriad versions of herself spanning many dimensions in trying to head off apocalypse caused by her disaffected daughter’s embrace of nihilism. As with their precursor film, Kwan and Scheinert tried to present a metaphor for life through the prism of fantasy gimmicks, wu xia tropes, and magic-realist glee, and for a while, at least, the film was a giddy romp. The excellence of the cast, including Michelle Yeoh, Jamie Lee Curtis, James Hong, and a surprisingly, wonderfully renascent Jonathan Ke Huy Quan, also helped. But the film dragged out every conceit and set-piece to a painful extent, and fell victim ultimately to an increasingly tedious blend of hipster smart-assery and shallow feel-good messaging, trying ultimately to use its po-mo, multi-culti posturing to give a new gloss to well-worn indie film tropes.

Lei Qiao’s The Hidden Fox was an actual, proper wu xia flick that took plain inspiration from both Zhang Yimou’s Shadow, in imitating its smoky-textured and desaturated visuals applied to dazzling, acrobatic fight scenes, and Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight, with its cast of colourful villains known as the Eight Evils. This gang are introduced in the employ of a corrupt government official seeking a legendary treasure, engineering a deadly duel between two heroes and massacring a village all to clear their way. Ten years later, they’re put on the path to the treasure again and dispatched to an isolated, snowbound locale, only to find someone in their midst isn’t who they say they are. The Hidden Fox had some problems that have beset recent wu xia, particularly overripe performances and a script that only engaged its characters in the sketchiest terms at first and piled on narrative gimmicks in spite of not really being that complicated. Qiao’s fearsome action scenes and great photography made up a lot of ground: this might well have been the year’s best-looking film alongside Avatar: The Way of Water at much less cost, and as it barrelled towards a climax Qiao worked up some of the operatic emotional force the genre commands so easily at its best.

Latter-day Master of Disaster Roland Emmerich tried damn hard to pretend it’s still 1998 with Moonfall, a throwback to his classical brand of big, dumb special effects extravaganzas, albeit this time with a big, dumb sci-fi idea to justify it, proposing that the moon is a gigantic, encrusted alien mechanism that one provoked to action begins causing havoc on Earth and requires some affordable, available movie stars to save the day. Said movie stars included Patrick Wilson as the disgraced astronaut getting his shot at redemption and payback and Halle Berry as his once-and-future co-pilot, backed up by John Bradley, bringing his patented porky-plucky nerd hero into a contemporary setting. The film didn’t just demand turning your brain off but pulling it out of your skull and placing it in a pickling jar, and Emmerich’s touch just hasn’t been the same since he stopped working with Dean Devlin, his movies afflicted by a sterile aesthetic designed to be redubbed with ease for foreign markets. Fair’s fair though – it had just enough headlong, pulp magazine energy and absurd spectacle, delivered with Emmerich’s trademark graphic fluidity, to make me want to play along, particularly as this kind of movie’s been sidelined so long by superhero stories.

It’s long felt possible that the classic high-powered, jingoistic Hollywood action-adventure movie from the ‘80s and ‘90s, still beloved by boys of all ages and from all places but now stuffed away in Tinseltown’s locker in vague embarrassment in favour of superheroes and high-concept IP farming, might find new life outside of the US, much as the Western once did. Indeed, some movies out of Scandinavia in the past few years have already tried it. Australian pulp author Matthew Reilly offered his take, with his directorial debut Interceptor. Reilly cast Elsa Pataky, aka Mrs Chris Hemsworth, as a dauntless but ostracised soldier assigned to a floating command centre for the US’s missile defence system, who finds herself fighting to hold off a glib megalomaniac’s efforts to break in and disable the system, leaving the US vulnerable to nuclear annihilation. Kickboxing, gunplay, and corny CGI aplenty ensue. Reilly delivered a cheerfully cheesy, low-budget attempt to approximate that old school blockbuster vibe, complete with lots of Aussies doing dodgy American accents and a heroine whose Spanish lilt despite being the daughter of a respected US soldier is explained in a passage of ADR. The concoction was flimsy but delivered where it counted, and Pataky’s authentic physicality was utilised brilliantly. Reilly also wove in stabs at hot-button social commentary, including the heroine’s history with sexual harassment and the villain’s desire to cleanse his nation of its fractiousness, that were at once goofy and oddly substantial. Hemsworth made a funny cameo as a dopey salesman cheering on the heroine.

Hemsworth meanwhile returned to playing his most beloved character for Thor: Love and Thunder, a second helping of Taika Waititi’s distinctive take on the Norse god turned Marvel superhero. This time Thor, totally ripped once more and playing the zany wildcard in space adventures with the Guardians of the Galaxy, was suddenly drawn back to Earth and forced to confront his ex, Jane Foster (Natalie Portman), who’s terminally ill with cancer but has also been reborn as a new, female Thor. Together they battle Gorr the God Butcher (Christian Bale), whose sobriquet says it all. Where Waititi’s previous Thor: Ragnarok succeeded in applying self-satirising humour and an ‘80s cartoon aesthetic to fantasy and space opera tropes, Love and Thunder offered a darker, potentially very rich story contending with tragedy and revenge, but also threw comedy at it incessantly, as if scared of getting too heavy for the eight-year-olds with plastic Mjolnirs in the theatres. Waititi waded through his own sticky melange of childish fervour and hipster cynicism, offering up such try-hard delights as Russell Crowe as a hard-partying, plummy-accented Zeus and some screaming, cosmos-traversing magic goats. Waititi’s occasionally striking visuals were foiled and the excellent cast wasted.

Sam Raimi, who helped birth the superhero craze with his first Spider-Man twenty years ago, returned to the genre to helm the MCU entry Doctor Strange In The Multiverse Of Madness. This one saw Benedict Cumberbatch’s mystic master drawn into a dimension-hopping adventure when he encounters America Chavez (Xochitl Gomez), a girl gifted with the capacity to leap between realities. America is being pursued through time and space by a mysterious enemy seeking to control her powers, a foe Strange learns soon enough is all too familiar and might well be unstoppable: Elizabeth Olsen’s Scarlet Witch, turned maniacal and broody after losing her beloved Vision. Raimi got away with surprisingly strong doses of his mischievous humour and invention as well as oddball, morbid imagery, which lacked only, in wielding the full force of Disney-Marvel’s special effects teams, the handmade charm of his early films. Raimi was also willing to countenance a once-heroic character’s downfall with a modicum of seriousness, and sequences like a mystic battle fought with musical notes had just the right crazy energy. That said, a mid-film pause to exploit the dimensional shift for some franchise blurring and nostalgia-baiting just got in the way, and the storyline was in such a rush it failed to make all its hero-journey beats land properly.

Meanwhile, another venerable fantasy franchise curled up like a dead spider, with David Yates’ Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore. The third entry in this prequel series saw magizoologist Newt Scamander, his brother Theseus, and sundry pals trying to prevent archvillain Grindelwald from getting himself elected leader of the wizarding world through machinations involving a magical version of a groundhog. Given the lumpiness and lack of focus of the previous two entries, The Secrets of Dumbledore tried to turn things around by pairing screenwriter J.K. Rowling with Harry Potter adaptor Steve Kloves. But this one proved just as awkward, in trying at once to provide a potential capper for a series that was supposed to go much longer whilst leaving the door open for continuation. This meant major storylines were rushed and then given cursory climaxes, and largely displaced by a core plot that tried to articulate a strained commentary on current politics, which might have hit differently if Rowling’s big mouth hadn’t dug her so deep a hole of late. Eddie Redmayne’s Newt had become a bore and Katherine Waterstone’s Tina was largely missing in action, which is a problem when they’re the core heroes of the enterprise, whilst Callum Turner’s nominally more stolid and traditional Theseus iroically emerged as more engaging.

After the calamity that was their previous collaboration, the only place for Jaume Collet-Serra and Dwayne Johnson to go was up, and the returned this year with Black Adam, revolving around one of the more antiheroic figures in the DC comics pantheon. Johnson was the title figure, a magically endowed ancient superwarrior with a grimly wrathful streak revived in the present day to protect his homeland of Kahndaq from an army of slimy mercenaries that’s taken it over for plundering. He’s soon pulled into conflict with a team of more traditionally righteous superheroes called the Justice Society, and all eventually are obliged to battle a descendant of Adam’s ancient foe. Black Adam actually started pretty well with and wielded a decent streak of dark humour, whilst Collet-Serra’s eye really let rip on some spectacular action sequences, particularly with Adam’s initial emergence, set to “Paint It Black.” I also liked the casual approach to introducing the Justice Society, a gang comprised of relatively obscure DC heroes, and setting them and Adam at odds in a story that did actually manage to approximate some of the random craziness of classic comic books. The problem was the film smacked of Warner Bros.’ uncertainty in going for wall-to-wall action for way too long.

I could make many of the same comments about Ryan Coogler’s over-everything Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, the inevitable sequel to his zeitgeist-defining 2018 hit. Wakanda Forever sported in Namor a very similar figure to Black Adam, as another formidable antihero defending his nation. In Namor’s case the realm he sought to protect was the aquatic city of Talokan, determined to remain unmolested by a world hungry for Vibranium resources which until now Wakanda seemed to have the monopoly on. With King T’Challa dead from sudden illness and his young sister Shuri forced to step into his shoes, the two nations finished up warring for contrived reasons. Wakanda Forever was certainly a profound mess, jerkily paced and far too long, telling a story that scarcely made sense and with an array of MCU make-work shoehorned in, including introducing the absurd teenage genius Riri Williams, as well as dealing with the obvious and critical damage done to its prospects and narrative clarity by Chadwick Boseman’s death. Attempts at extending the first film’s political edge were even more clumsy and self-contradicting. Somehow though, I found it an intermittently likeable film, particularly in giving Leticia Wright’s Shuri space to evolve as a grief-stricken and angry new hero, backed up with strong performances by a battery of major actresses. Coogler and his megabudget production wielded some amusingly lush visuals depicting the two quasi-tribalistic superpowers going to war: Coogler confirmed at last that he does have an interesting eye, even when it’s at the mercy of CGI slathering and dark digifilm textures.

Simon Kinberg, back to deliver more mediocrity after his X-Men movie, directed The 355, a thrill-free thriller about an array of badass female security agents chasing down a MacGuffin and forced to work together despite their rivalries when caught up in a melange of double-crosses and conspiracies. The film brought together a marvellous array of actresses, headlined by Jessica Chastain again trying to get her action mojo working, and backed up by Diane Kruger, Penelope Cruz, Lupita Nyong’o and more. Despite such an array of talent wielding years of accumulated affection, The 355 finished up such a derivative affair, replete with make-work plotting and lumbering action, that I didn’t finish watching it. Anthony and Joe Russo’s hugely expensive streaming epic The Gray Man was slightly better but basically the same cookie-cutter product, this time based on a popular series of airport novels, casting Ryan Gosling to do variation #3.12 on his stoneface-with-slightly-wry-tweaks act whilst playing a criminal refashioned into an omnicompetent assassin, who goes to war with a CIA cabal to save the daughter of his mentor. The film had muscular production values thanks to its absurd budget and sported an entertaining turn from Chris Evans as the smarmy villain, but it was little more than an accumulation of genre clichés and algorithm-based keywords, with a dingy, flavourless look that managed to make every globetrotting location look the same, and no idea how to fit its story and character elements together. If this is what the future of cinema is, I feel deeply depressed.

Just as depressing was Ruben Fleischer’s Uncharted, adapted from the much-loved video game about roguish adventurer Nathan Drake, with Tom Holland playing Drake in a nominal origin story, as the barista orphan falls in with a roguish mentor played by Mark Wahlberg in premium smarm mode and sets out to find a long-lost treasure, competing with various roguish competitors and roguish quasi-love interests. Uncharted pilfered freely from a vast array of classic adventure stories and movies and completely drained them of all hints of life, sex, blood, danger, and excitement, substituting soulless digital photography gloss, boring and annoying heroes, and a ridiculous villain. Holland, Wahlberg, and Antonio Banderas delivered shameless in-it-for-the-money performances. The finale had a potentially entertaining if absurd conceit as heroes and villains battled it out on Spanish galleons dangling from helicopters, but even that finished up a whole lot of nothing.

Aaron and Adam Nee’s The Lost City looked almost exactly the same as Uncharted, with its phony-looking digi-jungles, although it aimed for quite a different spin for its pilfered tropes. The Nees stole the basic proposal of Romancing The Stone – romantic novelist gets thrust into a real adventure – whilst giving it a slight makeover. This time the novelist was Sandra Bullock’s successful but self-deprecating scholar turned hugely popular trash writer. The love interest was a likeably dopey male model who provides the looks for the hero on her book covers and has a secret crush on the author, played with winning fortitude by Channing Tatum. The latter chases the former when she’s kidnapped by a playboy villain (Daniel Radcliffe, amusingly cast but uninspired), to tap her authentic knowledge about an ancient treasure. At least The Lost City proved a mildly spry and painless take on recycled ideas: too much of its humour was that brand of semi-improv yammering that’s everywhere these days, but Brad Pitt was great in a cameo as a he-man adventurer hired by Tatum to save the day only to casually die, and Bullock and Tatum had just enough chemistry to make the rest of it an okay time-waster.

Tom Gormican’s The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent tried a brand of meta storytelling that’s become increasingly popular of late. Nicolas Cage played Nicolas Cage, or rather a version of the popular impression of his career as an earnest but livewire talent cursed with poor judgement, who likes arguing with another, even more caricatured version of that persona that sometimes appears to him, one who likes howling out weird line readings. ‘Cage’, facing career downturn and problems relating with his ex-wife and teenage daughter, wearily accepts an offer to collaborate on a project with an amateur but very wealthy screenwriter, played by Pedro Pascal, who’s a huge fan. To both men’s surprise they become great friends, but Cage is soon warned by some CIA agents that his new pal is an arms dealer involved in a recent, high-profile kidnapping, and is asked to spy on him. The script’s pitch wasn’t entirely original in its ironic juxtaposition of humdrum lifestyle jokes and mutually-boosting buddy shtick against outsized melodrama and genre film canards. Cage however had a high old time simultaneously exalting and mocking his screen persona, and the plot, as well as delivering a suitably over-the-top approximation of buddy comedy shading into absurd action flick, had some fun with the idea of an actor using acting skills as another weapon in the arsenal.

Tom George’s See How They Run also applied a comic and aggressively metafictional approach to a thriller blueprint, splitting the difference between honouring and burlesquing one of the most famous whodunits ever penned, Agatha Christie’s never-ending play The Mousetrap. George’s film had a potentially fun and clever gambit, setting a murder mystery backstage of the play when it was still a relatively fresh hit, and roping in some of its real-life stars including Richard Attenborough, Sheila Sim, and Christie herself, whilst also presenting a smart-aleck spin on the play’s plot. Adrien Brody was the jerk Hollywood director murdered by persons unknown, Sam Rockwell the sleepy, depressed, suggestively named investigating cop Inspector Stoppard, and Saoirse Ronan his bright and eager young assistant. George applied a lot of colourfully stylised jokiness derived rather too blatantly from the likes of Wes Anderson, and one late touch had real potential, as Shirley Henderson was cast a frayed and batty Christie who tries to intervene in a stand-off by clumsily applying her literary art to life. The script otherwise had an awful paucity of good jokes or substantive characters it took seriously enough to lend the larkishness a fulcrum, and failed to gain much momentum from the disparity of fact and fiction because it had no feel at all for reality, so the whole thing only added up to a superficially energetic pastiche.

Munich: The Edge of War was based on a novel by Robert Harris exactly the same as every other Robert Harris novel, with the same basic plot applied to varying historical backdrops. This one unfolded against the 1938 Munich Conference, casting Jeremy Irons as Neville Chamberlain and George Mackay as a young aide who tries to act as mediator between the Prime Minister and a German friend who aims to blow the whistle on Hitler’s conquering intentions. The film was helmed by German director Christian Schwochow, which raised the possibility of a new perspective on this kind of gathering storm tale. It didn’t stop the results from being insipid as a thriller and distracted as a portrait of a much-mythologised historical pivot, punctuated by such obvious touches as casting August Diehl yet again as a nasty Nazi. The movie was only made vaguely memorable by Irons’ crafty, convincing performance as Chamberlain, trying to apply all his diplomatic wiliness to preventing war with earnest motives but also far out of his depth in dealing with authentic evil.

Greg Mottola’s Confess, Fletch revived the wily journalist, alias-happy investigator, and all-round wiseass created by Gregory McDonald and played in two movies in the ‘80s by Chevy Chase. Jon Hamm was an inspired choice for the role, playing a Fletch who’s quit journalism and, whilst living in Rome, gets involved with a Count’s daughter. He returns to the US to help unravel the theft of some of her family’s art collection, only to find himself accused of a murder. Attempts to revisit the appeal of cultish literary antiheroes can sometimes go wrong – remember Mortdecai? – but Mottola was judicious in updating the material and applied a smart, snappy sense of style. Almost to a fault: the comedy didn’t have much time to breathe as it was so determined to speed from one wisecrack and quirky vignette to the next, which meant the film almost outwore its welcome at just over an hour and a half. Still, it was for most of that length an elegant, playful, old-fashioned entertainment, with a script peppered with genuinely funny lines, and a pretty good mystery in an extended lampoon of Chandleresque thrillers.

Kenneth Branagh’s Death On The Nile finally came out early in the year, just a few weeks in fact after his Oscar-nominated Belfast, after being incessantly delayed by COVID and controversies involving several of its stars. For his second go-round as Hercule Poirot, Branagh tackled one of Agatha Christie’s most famous stories, with murder and skulduggery unfolding mostly on a paddle steamer working its way up the Nile. Branagh was bolder this time in suborning the ritual form of the whodunit to his own fascination with formative psychology and cine-theatrical staging. He painted Poirot more overtly as a damaged misfit posing as suave force of justice, and surrounded him with versions of Christie’s characters tweaked to emphasise hidden passions and expose new forces, cultural and carnal, blending to push aside the posh Englishness Christie’s writings mythologised. Gal Gadot was ineffectual as the key victim, but Emma Mackey sizzled as her randy, vengeful sister, and Branagh’s freewheeling direction ticked off influences as diverse as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and Bollywood epics. The last scene in particular struck a truly odd and affecting note, and the film, for all its wayward impulses, emerged deeply stamped with Branagh’s personality.

Rian Johnson’s more impudent take on the set-in-stone whodunit template Knives Out proved so popular in 2019 that this year he returned with a follow-up, Glass Onion, this time sending Daniel Craig’s sartorial detective genius Benoit Blanc to a Greek island owned by Edward Norton’s obscenely rich and tasteless tech mogul and his coterie of obeisant frenemies, gathered nominally for fun and frivolity, only to find murder and mayhem ensuing. This time around Johnson reiterated most of the core concepts from the first film in a more inflated and self-conscious manner, including offering a new raft of satirical caricatures seeking to skewer obnoxious species in the contemporary landscape of fame and wealth. Whilst Craig’s Blanc remained an inspired characterisation and held the film together when on screen, and Johnson’s filmmaking has become slick in the extreme, the second helping was far, far less satisfying, and indeed indicative of Johnson’s worst instincts. Johnson’s new mystery, which tried to build a key joke around things being less complicated than anyone wants them to be, still crammed proceedings with busy-work to provide an illusion of complexity, whilst the satire was one-note, and overall the incessant “fun” choked off any actual fun, any chance to enjoy the actors and let the characters and ideas flourish.

It’s easy to forget given his perpetually looming pop culture status that Batman is another beloved detective hero born just a few years after Poirot. The character made yet another retooled return in Matt Reeves’ The Batman, a film that pushed certain tendencies for the character and his cinematic portrayals to a limit, making him the hero of a long, moody, ‘80s-style neo-noir film. Reeves avoided offering yet another origin recapitulation, and instead portrayed the Dark Knight fairly early in his crimefighting campaign, contending with both Gotham City’s gang lords and the vicious, agenda-driven vigilante calling himself The Riddler, whilst getting involved with thief and demimondaine Selina Kyle, a rival and helpmate in his assault on the underworld with a secret project of her own. I liked The Batman quite a bit: Reeves applied a careful blend of stylisation and realism to a solid, well-told story, creating a slightly cyberpunk Gotham, and his filmmaking was elegant. Robert Pattinson was surprisingly, smartly low-key as a Bruce Wayne who barely has an identity beyond the nightfaring guise he’s constructed for himself, and Kravitz had a sly intensity as a Catwoman with a very personal thirst for justice. Only the overbusy script and occasionally ponderous length got in the way of the film’s total success.

As well as contributing one of his best scores for The Batman, Michael Giacchino also emerged as a director of potential when he helmed a Marvel by-product, the odd little amuse-bouche Werewolf By Night, based on one of the imprimatur’s more cultish and grown-up properties. Werewolf By Night mimicked classic Universal-style Horror movies in form and look, particularly Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat, as it depicted a gang of notorious monster hunters converging at a mansion to participate in a monster hunt to prove themselves worthy inheritors of a magical object called the Bloodstone. Laura Donnelly was the spunky black sheep daughter of the Bloodstone’s old master and namesake, Gael Garcia Bernal the guarded nice guy with a feral secret, and Harriet Sansom Harris had a high old time as Donnelly’s fearsome, fanatical mother-in-law. Giacchino proved himself competent and well-steeped in the mystique of the kind of classic fare he ape, even if the black-and-white photography wasn’t terribly well-attuned to the medium. It’s also a pity the script didn’t learn more lessons from the old B-movie models with their ability to sharply sketch characters in a few minutes, where Werewolf By Night felt like a long prologue for a longer movie that doesn’t yet exist. Still, taken within its self-prescribed limits it was fun.

Joseph Kosinski’s Top Gun: Maverick, which finally hit screens after a long COVID delay, was always going to be a hit, but the degree to which it proved not just the year’s biggest success but an all-time blockbuster took everyone by surprise, casually turning many assumptions of current mainstream cinema on their head. Kosinski anointed Tom Cruise, returning to his career-making role as ace pilot Pete ‘Maverick’ Mitchell, as a logical extension of his fantasy figure status, undimmed by age or compromise, and as the last true movie star. He was thrust into a storyline just about as old as Hollywood itself: the aging Maverick, almost out of options despite being a glory-crusted hero thanks to his penchant for bucking the system, was assigned to train and eventually lead some young pilots for a good old-fashioned impossible mission, requiring him to make peace with the past on the way as he struggles in a quasi-paternal role for Rooster (Miles Teller), son of his old pal Goose and vanguard of the next generation. Kosinski managed a genuinely unexpected alchemy, playing off the mystique of Tony Scott’s slick and silly 1986 original, but also moving far beyond it, turning the sequel into a more general paean to classic Hollywood virtues – showing a beloved star and good-looking people doing thrilling, spectacular things, and tapping it for emotional depth, particularly in the vital meeting between Cruise and an ailing Val Kilmer. As a work of dramatic art I found it a double-edged blade – movies just like it, if not so visceral, came out every other week in the 1950s, and that familiarity was both appeasing and also a little wearisome. The compensation was Kosinski’s cutting-edge style and genuine sense of big-screen spectacle.

Only a few weeks after releasing the biggest hit of the year, Kosinski saw his follow-up Spiderhead more or less dumped. Spiderhead had a reasonably familiar starting point – condemned criminals try to expiate their sentences and their mental demons by signing up to be guinea pigs for a mad scientist’s experiments, in this case being dosed with drugs that can finely control mood and behaviour. But Kosinski’s approach to this concept was to, at least initially, play it as a bright, shiny lampoon on the softly fascistic self-confidence of techie entrepreneurs, playing the beneficent geniuses whilst heedlessly ignoring actual consequences for human beings, and the bromides of online poptimism, before the troubling truth begins to infect proceedings. Chris Hemsworth delivered an inspired performance as the beaming, snazzy, palsy supervisor for the experiment who pretends to be a functionary but is actually the master of puppets, and Miles Teller was solid as one of his subjects, guilt-ridden but increasingly assured in his resistance. The key problem with the film, despite some formidable qualities, was the story was just a little too straightforward to sustain a whole feature, being the sort of thing The Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits might once have knocked over in half an hour. Subplots never quite became substantial enough to sustain themselves, the climax didn’t resolve too gracefully, and Kosinski, strong a formalist as he is, doesn’t yet have quite the touch for this kind of off-beat satire.

Following Top Gun: Maverick’s release, the movie event of 2022’s second half was the arrival at long last of James Cameron’s sequel to his epochal 2009 hit Avatar, a release that bore a heavy burden in trying to restore some wonder to the special effects blockbuster and the theatrical experience in general. Avatar: The Way of Water saw Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), Neytiri (Zoe Saldana), and their brood of kids forced to uproot from their jungle home when the return of human colonists and their great personal enemy Miles Quaritch (Stephen Lang), who has suffered a curious kind of reincarnation as his mind has been rehoused in an avatar body, sparks new conflict. Taking refuge with a sea-dwelling Na’vi populace and coming to love their lifestyle despite clashes between the Sully youngsters and snooty local brats, the Sullys are eventually forced to go to war again as Quaritch’s vendetta becomes increasingly unhinged. Cameron didn’t really try to do much new in terms of story and theme, beyond a swerve into a different brand of slightly masked environmental hectoring (swapping save the rainforest for save the whales), and shifting to a new locale for his particular brand of lysergic travelogue. Many of the fresh threads involving the conflicted and hybridised identity of the next generation introduced through characters like Kiri (Sigourney Weaver), the bemusing child of Dr Augustine from the first film, are destined to carry over into further sequels. The Way of Water came on with such maximalist passion and spectacle that all this didn’t really matter much, with Cameron’s astonishingly beautiful filmmaking woven around a sufficiently elemental story that built to a thunderous action climax that amongst other things provided a greatest hits collection of Cameron’s cinema and retold Moby Dick from the whale’s point of view, reiterating that Cameron has cojones the size of California.