.

.

Director/Screenwriter: Terrence Malick

By Roderick Heath

Terrence Malick’s late period has seen him more productive than ever at the cost of robbing his output of the almost magical allure it once had through scarcity. Once he was easy to idealise as an emissary of artistic stature redolent of a very different time and cultural frame, the reclusive poet broadcasting occasional, deeply considered artistic happenings from on high. But when he brings out three films in five years, he becomes just another filmmaker in the marketplace. Yet his work has defied the usual crises and swerves that befall aging auteurs to become ever more personal, rarefied, and bold, charged with a sense of questing enthusiasm and expressive urgency. Whereas in his early work I tend to find what Malick wants to say a bit obvious even as he laboured to say it in the most ravishing way, his later work suggests an attempt to articulate concepts and emotions so nebulous and difficult they cannot be conveyed in any meaningful way except when bundled up in that strange collection of images known as cinema, gaining a sharpness and urgency that risks much but also achieves much. This is a large part of why I’ve been moving against the current and digging what Malick’s been putting down all the more since The New World (2005). The New World marked a point when Malick really first nailed the aesthetic he’d been chasing, apparently formless in the usual cinematic sense, but actually fluidic and dynamic, more like visual music than prose, his stories unfolding in a constant rush of counterpoint, the visual and the verbal, each nudging the other along rather than working in the usual lockstep manner of standard dramatic cinema.

.

.

By comparison, I recently revisited Days of Heaven (1978) and find it gorgeous but inert, like a fine miniature in a snow cone. The pursuit of a horizon glimpsed in a dream, at once personal and lodged in a folk-memory, admirably articulated, but too refined, too stringently, self-consciously fablelike to compel me. The New World finally set Malick free because it allowed him to alchemise his preoccupations and poetic ideas, his obsession with the Edenic Fall, into the simplest vessel whilst still engaging with concrete history and a very solid sense of the world. Somehow Malick has become, in his old age, at once the wispiest of abstractionists and the most acute of realists. Knight of Cups feels like another instalment, probably the last, in an unofficial, but certainly linked cycle he started with The Tree of Life (2011) and followed with To the Wonder (2013). Malick has been translating his own life into art for these films, albeit tangentially, through a mesh of disguise, displacement, invention, and simple reflection. Knight of Cups completes the sense of journey from songs of innocence to songs of experience; the depiction of childhood’s protean possibility rhymed with adulthood’s regretful mourning as depicted in The Tree of Life has given way to the specific portrait of love found and lost in To the Wonder, and now, hedonistic abandon and the open void of modernity amidst the elusive promise of the land. It’s a report in the moment that rounds off the tale Malick’s been contemplating since The New World, a portrait of what’s become of that innocent land the white man conquered.

.

.

Christian Bale inhabits the role of Rick, a screenwriter living it large in Los Angeles, but dogged by a lingering inability to form real emotional connections and the gnawing onus that is the fate of his family. That’s just about all the plot there is to Knight of Cups, which unfolds like a fever dream of recollection, pushing the flowing, vignette-laden, high-montage style Malicks’s pursued since The New World to a point that is both an extreme and also a crescendo. In compensation, Malick adopts a very simple, but perfectly functional division into chapters, each named for a card in the Tarot and dominated by a depiction of one of Rick’s relationships, whether passing or substantial, with various women and family members, or turning points in his experience. “The Moon” recounts his grazing encounters with dye-haired young wannabe Della (Imogen Poots). “The Hanged Man” depicts his uneasy relationship with his father and brother. “The Hermit” follows Rick through the indulgences of Hollywood, attending a party hosted by mogul Tonio (Antonio Banderas). “Judgment” sees him briefly reconnecting with his ex-wife, medical doctor Nancy (Cate Blanchett). In “The Tower,” Rick is tempted by Mephistophelian manager Herb (Michael Wincott). In “The Sun,” he becomes mesmerised by a fashion model, Helen (Frieda Pinto), who embodies pure beauty and practises tantric yoga. “The High Priestess” sees him hooking up with stripper Karen (Teresa Palmer), and visiting Las Vegas with her for a dirty weekend. In “Death,” he becomes involved with a married woman, Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), who falls pregnant and doesn’t know if the father is Rick or her husband. Finally, “Freedom” depicts his ultimate decision to leave Hollywood and finding happiness with Isabel (Isabel Lucas), a girl he often sees dancing on the beach.

.

.

The Knight of Cups is also a tarot card, of course, one that notably changes meaning according to how it’s looked at, encompassing the alternately quicksilver brilliance and inane nature of the young adventurer and will to disorder, a reminder of the closeness between the two. Rick is evidently the Knight, one who is not so coincidentally often in his cups. He’s also correlated with the prince in a fairy tale his father is fond of who travels to a distant land on an important mission but is bewitched by a magic potion and forgets his identity. Near the start of the film, Rick meets with two agents (Patrick Whitesell and Rick Hess) who have orchestrated his transfer off a project on which he was floundering and attached him to a top comedy star, a move that brings Rick to the peak of his profession. Rick lives nonetheless in a small apartment that barely displays any sign of real human habitation apart from his bed and laptop, as two thieves find to their chagrin when they break in and try to rob the place. He is shaken by an earthquake close to the film’s beginning, the first momento mori that jars him out of any sense of confident self-satisfaction. Soon, Rick wanders the city gobbling up sensations and distractions. He cavorts with models, actresses, and scenesters he can now pull with his growing wealth and freewheeling enthusiasm, but is nagged at by the omnipresent evidence of a concurrent reality, represented by the down-and-out folk he brushes against on the streets of LA.

.

.

The film’s prologuelike opening scenes see Rick on the town, riding the streets with models and partying hard in scenes of ebullient, carnivalesque high life, where geishas and costumed artistes frolic and life seems utterly ripe. An experimental film being projected on the wall invades the film itself, a beautiful woman shifting through guises, masks of cardboard and make-up floating around her face, identity turned protean and cabalistic—essentially introducing the basic theme of the film around it. Then, the earthquake shakes the town. In the first “chapter,” Rick meets Della, who describes Rick’s problem as one commonly diagnosed in writers by those close to them: “You don’t want love—you want a love experience.” But she also recognises that he’s a man who’s been switched off on some fundamental level for some time. She begs him not to return to such a state again, and the rest of the film depicts his struggle to really feel and open himself up. Rick’s deeper spiritual and emotional maladies are soon revealed as he visits his father Joseph (Brian Dennehy) at his offices, in a strange sequence that might be memory, dream, or a blend of the two, as Joseph seems to be alone in a vast building and washes his hands in filthy water. Joseph’s health and sanity become niggling sources of worry for Rick, whilst Joseph boils over with Learish anger and sorrow. Rick also maintains an uneasy relationship with his brother Barry (Wes Bentley), a former junkie turned street minister, often submerged in the shoals of human wreckage Rick contends with. These three beset survivors are closely bonded by rivets of love and wracking pain because of the suicide of a third brother, Billy. When any of the three come together, they often clash, sometimes in heated and physically eruptive manner: a dinner the trio have together devolves into Barry hurling furniture around.

.

.

Rick’s success has been achieved by remaining switched off because of a fear he admits in contemplating his failed marriage to Nancy. Nancy, in a motif reminiscent of Javier Bardem’s minister in To the Wonder, is glimpsed treating broken and sickened individuals from the fringes of society, contrasting Rick as he eddies in a zone where he’s aware of his inconsequentiality even as he experiences a very real sense of burden. Joseph’s thoughts are repeatedly heard in voiceover, as if the ailing father is trying still to guide his Rick, who, nominated as the successful progeny, wears the double burden of fulfilling the familial mission and holding up, psychically if not financially, the remnant of their pride and prospect. But Rick’s perspective is not just one of fashionable ennui: it’s one that touches everything he sees with a sense of charged fascination and transient import and meaning. One of the film’s high points is also one of its seemingly most meandering and purely experiential, as Rick wanders Tonio’s estate surrounded by a boggling collective of random celebrities and pretty faces. Rick explores the gaudy environs of Tonio’s manse, a gigantic placard advertising tasteless wealth, a neo-Versailles, whilst on sound we hear Tonio’s explanations of his love life, comparing his womanising habits to daily cravings for different flavours of ice cream, the confession of an easy sybarite.

.

.

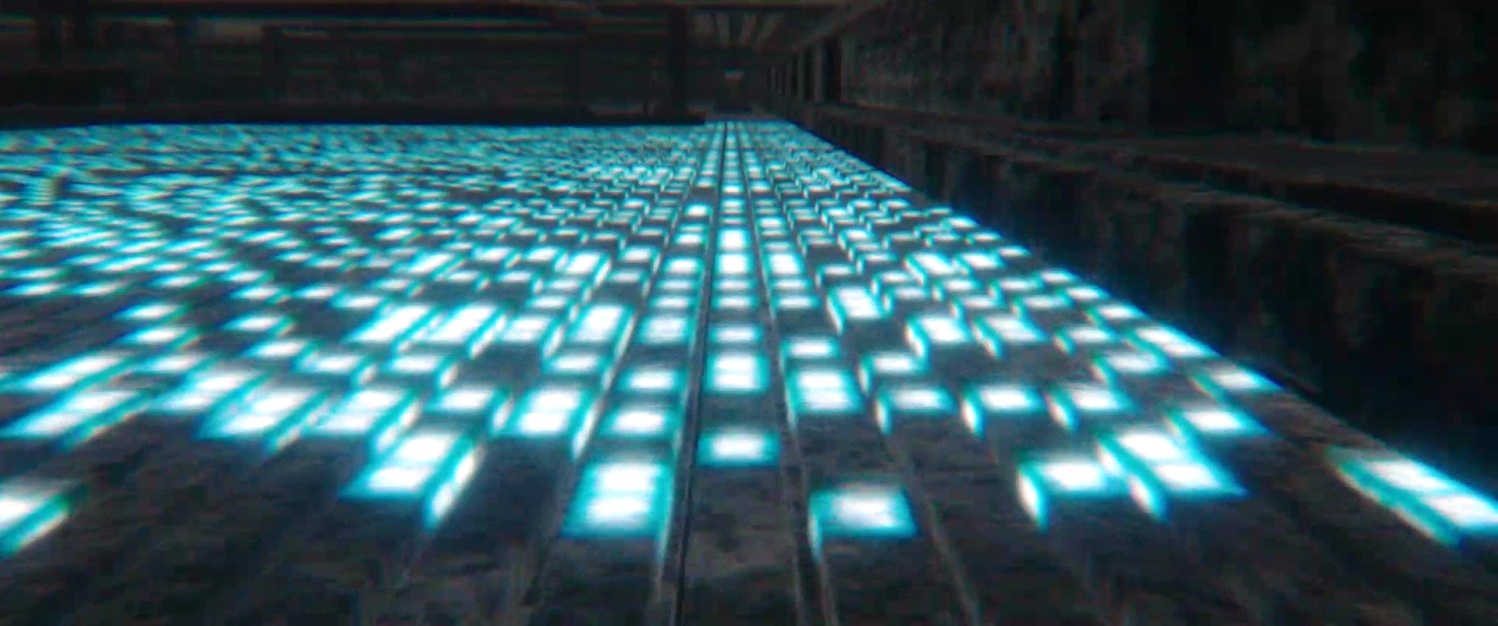

At first, the smorgasbord of flesh and fancy is bewildering and entertaining, the perspective that of a professional rubbernecker, but as the day goes on, booze is consumed, people dance and cavort, and eventually start plunging into the pool. Malick commences this sequence with shots of dogs chasing balls in the water, and then models dressed in haute couture similarly immersed, complete with giant heels digging at the water. He sees something both beautiful and highly ridiculous in visions where rose petals flitter through the air to rest on the shoulders of the anointed, straight out of some neoclassical painter’s concept of decadent pleasures in the days of Rome. By the end, everyone’s in the water, squirming in the liquid, a crescendo of absurd yet affectionate observation of the desire many have to exist within a perpetual party. The LA setting robs Malick of his usual places of meditative peace, the wavering grasslands, the proud sun-scraping forests. Swimming pools, the omnipresent symbol of prosperity in LA, become under Malick’s gaze numinous portals aglow with fervent colour, places where the moment anyone enters they instantly transform into a different state of being. They’re tamed versions of the ocean, a place Rick constantly returns to with his women or by himself, the zone of transformation and grand, impersonal force. Something of a similar insight to one Sang-soo Hong explored in his The Day He Arrives (2012), charges Knight of Cups, if in a radically different fashion, as Rick’s various relationships, whether brief or substantial, see him constantly returning to the same places and sights to the point where they seem both interchangeable and looping—going to the beach, driving the streets, visiting his girlfriends’ homes—evoking the evanescent rush of the early phases of love, but then each time seeming to reach a point where he can’t go any further. At one point he’s visited by old friends who knew him as a kid and have kids of their own, a zone of experience he hasn’t yet penetrated, emissaries from an alien land.

.

One noticeable lack from most of Malick’s earlier films was real, adult sexuality. After finally delving into that with To the Wonder, Knight of Cups is frankly sexy, as it portrays Rick’s successful entry into a zone that would strike a lot of young people as paradise. But there’s still a fascinating, childlike sense of play apparent in the film as Rick cavorts with naked nymphs he picks up. Malick moralises none of this, seeing it merely as the inevitable result and pleasure of putting a large number of good-looking, well-off people into a similar environment and letting them have at it. Knight of Cups brings the implicitly autobiographical narrative Malick wove through The Tree of Life and To the Wonder into a new phase, patterned seemingly after Malick’s time spent as a screenwriter in the early 1970s and leading up to his eventual self-exile from the movie industry. Again, of course, there’s good reason not to take all this simply as memoir, but rather as a highly transformed, aestheticized attempt to convert experience into poetry. That aesthetic is one of memory—fallible, fluidic, selective, associative. But there’s no hint of the period piece to the result, which is as stylistically and sociologically up-to-date as anything I’ve seen lately, engaging contemporary Hollywood and indeed the contemporary world in all its flailing, free-falling strangeness, the confused impulses towards meditative remove and hedonism apparent in modern American life.

.

.

Knight of Cups is, as a result, one of the most daring formal experiments I’ve ever seen in a feature film, an attempt to paint entirely in the mode of reminiscence, a tide of epiphanies. Malick’s early films were obsessed with the exact same motif of clasping onto a mood, a way of seeing, an impression from the very edges of liminal experience. But his techniques have evolved and transformed those motifs and are now inseparable from them. Knight of Cups seems random and free-form, but actually is rigorously constructed, each vignette and experience glimpsed as part of a journey that eventually resolves in some moderately traditional ways. Amidst Malick’s now-trademark use of voiceover to give access to the interior world and thoughts of his characters and music to propel and define various movements, he also adds snatches of recordings of poetry, recitation, and drama, including John Gielgud’s Prospero from Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books (1991) and lines from The Pilgrim’s Progress. With such hallowed, high-culture refrains snipped to pieces and rearranged into mantralike capsules of eerie wisdom ringing out, Knight of Cups finds a way to deal with the cornucopia, enfolding and smothering, that is modern life, as well as with Rick’s immediate personal concerns. Tto a certain extent, Rick is merely a scarecrow to hang it all on, the vessel of perception whose journey through life is, like that of all artists, one of both immersion and detachment.

.

.

And yet Rick is hardly a nonentity, or a cliché emblematic of Hollywood shallowness. If The Tree of Life and To the Wonder were overtly concerned with spiritual and religious impulses as well as the worldly matters of growth and love, in Knight of Cups, that has faded to background noise. Here Malick suggests constantly that in the modern world, the divides we used to be able to set up to corral zones of experience—enterprise, spirituality, sexuality, intellectualism—cannot be maintained in such an age. The urge of the spiritual seeker is still lodged deep within Rick, perhaps all the more powerful when stripped out of the pieties of childhood and small-town life and set free in the louche embrace of worldly plenty. Armin Mueller-Stahl appears briefly as a minister advising Rick on how to try to engage with life as he moves closer to making a real break. But the matter here is the allure of the profane, and indeed, an attempt to create a truly modern definition and understanding of it—the intoxicating, but also dispiriting effects of superficialities, the strange hierarchies that turn some people into the tools and suppliants. Some have seen this work as an anti-Hollywood moan, but it’s not the usual shrill satire or snooty take. The narrative does infer that Rick’s role in the film world is so inane that it barely registers in his stream of consciousness. The essence of Malick’s complaint seems to me that although the movie industry attracts, employs, and sometimes enriches artists, it so rarely asks them to truly stretch their talents, like making Olympic-level sprinters compete in three-legged races.

.

.

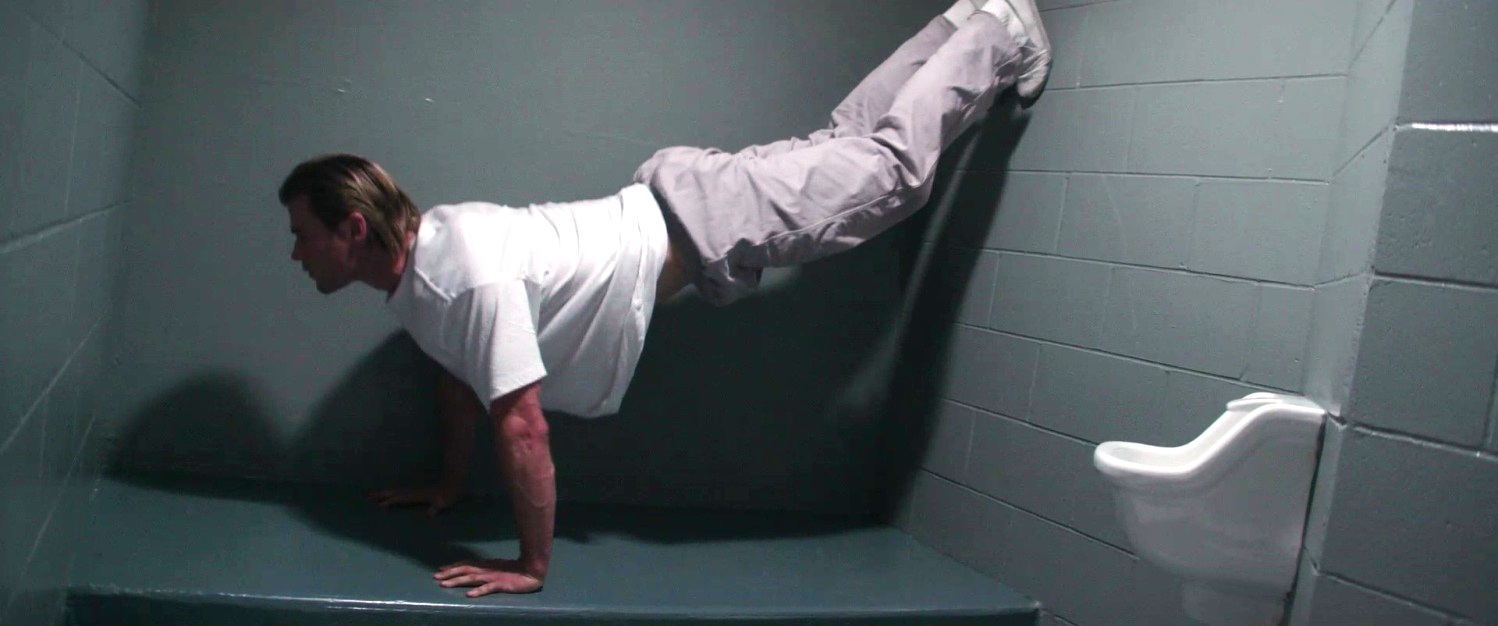

Malick actually seems to see Hollywood as rather comical, a candy castle for perma-adolescents. Rick’s dabbling in decadence is far from extreme: sometimes he gets blotto and has a lot of sex. Malick maintains much the same goggle-eyed, wide-open sensibility towards the strange places where Rick finds himself, from Tonio’s party to the pornocratic sprawl of Vegas and the strip club where he meets Karen. The placidity of a Japanese shrine offers the balm of calm, but Rick’s real transformative visions come amidst the partygoers of Vegas, a place that counts as some gigantic, if tacky, work of artistic chutzpah. There he gazes up at dancers dangling from the ceiling enacting a visualised myth of birth, slipping out of a chrysalis above the swooning, frenetic joyfulness of the people on the dance floor, an event of communal magnitude, something Rick is happy to exist within but cannot entirely join. Malick comprehends the magnetism of a place entirely dedicated to immersion in sensuality, a place where Rick lets the strippers lock him in a cage. Malick sees something genuinely telling here—that in the most adult of activities are the most profound expression of a desire to devolve back into the childhood, a place of play and free-form existence. But it’s also another stage for Rick to study to reveal his own persistent problem. It’s entirely logical then that in Malick’s mind, Karen, a bon vivant with a gift for moving freely and easily in the world, is probably the most complete and easy person glimpsed in the film, capable of chatting amiably with both pimps out in the surreal wilderness near the city and moguls ensconced in its gilt chambers.

.

.

Rick’s fascination with all his women encompasses their ways of interacting with the world and their individual identity, and also their commonalities, their mirroring points of fascination and ironic disparities. The faint, but definite glint of hard, ambitious intent in Della’s eye as a wanderer far out of her zone both rhymes with and also contrasts Karen’s similar status as a wayfarer, but one who has no programme in life other than giving herself up to experience whilst making a living in the profane version of Helen’s job. Rick’s regret at never having a child with Nancy segues into Elizabeth’s bitter, crucifying pregnancy. Rick’s own internal argument is actualised in glimpses of characters who bob through his life. Cherry Jones appears as a wisp out of his past, someone who knew him and his family way back and who recalls how he once told her he felt like a spy in his own life. Wincott’s Herb declares he wants to make Rick rich, but Rick contemplates his ruined father, who remembers that “Once people envied me…” and measures the ultimate futility of success as measured in exclusively worldly terms. The Tree of Life evoked Death of a Salesman in certain respects as it analysed the figure of the American patriarch, and here Malick’s casting of Dennehy, who found great success playing Willy Loman in a recent revival, is another tip of the hat to Arthur Miller’s work. At one point, Dennehy is glimpsed treading a stage before an audience, one of several fragments scattered throughout the film of a purely symbolic reality and glimpses of oneiric netherworlds buried deep in Rick’s mind, as his father has become an actor, a seer, a fallen king, Lear on the heath or Prospero with his magic failing on his lonely isle.

.

.

Malick’s methods chew up the talent he hires at stunning pace, but also presents an entirely democratic employment of them, in service of a vision that tries to encompass a sense of nobility in every individual. Knight of Cups is at once a display of Malick’s solipsism in this regard, his casual readiness to use a raft of skilled actors simply to inhabit the free-floating, sometimes barely glimpsed human entities that graze the camera in his films, and yet invigorating and reassuringly uninterested in the usual caressed egos of Hollywood film. Every performer is ore, mined for their most precise gestures, looks, words. Malick’s use of voiceover allows him to grant all characters their moment of insight and understanding as if gathering the fruits of years of contemplation, rather simply relying on what they can articulate in the flow of the banal.

.

.

Whereas To the Wonder suggested Malick’s intention was to incorporate aspects of dance and particularly visual art into film, here Malick’s artistic arsenal is rooted securely in the language of modernist literature, likewise reconstituted in cinema. The rush of images has the ring of Joyce’s technique and the very last word heard in the film, “Begin,” evokes the famous affirmative at the end of Ulysses, whilst the visual structure recalls John Cage’s take on Joyce’s aesthetics, “Roaratorio.” But Malick also shouts out to some of his filmic influences. Della is initially seen wearing a pink wig, recalling a Wong Kar-Wai heroine, a nod that acknowledges the influence on Wong’s free-flowing style and obsession with frustrated romanticism on Malick’s recent approach. Malick also reveals selective affinities with some signal cinematic gods for filmmakers of his generation: as with To the Wonder, I sense the imprint of David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago (1965) in presenting the main character as both actor and viewer in his life. The narrative, like many artistic self-contemplations in film, recalls Fellini’s 8½ (1963) whilst other motifs evoke Antonioni’s Blowup (1966) as Rick circles photo shoots, fascinated and knowing about the arts of creating illusory beauties whilst confronting interior voids.

.

.

But Malick ultimately rejects the roots of their works in a pernickety moralism that blends and confuses Catholicism and Marxism, chasing more a Blakeian sense of life and existence as a polymorphic surge that must be negotiated and assessed, but cannot be denied. Rick’s late agonistes with Elizabeth signal the end of the process Della identifies at the start, of Rick coming to life again but also facing the sort of emotional crucifixion from which his detachment spared him, both a price exacted and a perverse kind of reward found in genuine suffering: “It binds you closer to other people,” Mueller-Stahl’s priest notes. This event finally drives him out of LA, and he hits the road, exploring an American landscape of his youth and dreams that has forgotten him and that he, too, has forgotten. He seems to reconcile with his father and brother in a scene of violent catharsis, and takes his father to visit a former workplace, a heap of glowering, indifferent industry.

.

.

By the very end of the film, Malick signals that Rick escapes LA, settles down with a woman, and finds a certain level of peace and healing living in the desert. Isabel seems deliberately filmed more as an entity than a person, the archetype of the type of woman who has flitted right through Malick’s work, a dancer and a priestess who leads Rick into caves for candlelit rites whilst the mountains that Rick has envisioned as symbols of everything his life wasn’t now soar above him. It’s arguable that in such imagery Malick finally retreats into a safe zone of symbolism, where much of the value of Knight of Cups is that it’s a work well outside his regular purview. But the truly radical quality of Knight of Cups is how completely untheoretical it is, the power of lived experience blended with urgent need to express in the most unfettered ways welling out of that experience. It’s both an explanation and a blithe feat of expressive legerdermain, not caring if we keep up. It’s cinema, stripped to the nerve.