.

Directors: George Miller

Screenwriters: James McCausland, George Miller

By Roderick Heath

Australians have always felt oddly comfortable with the prospect of apocalypse. Perhaps it stems from the experience of dealing with a capricious continent that offers such wealth of space without the assurance of plenty to match. Or from the history of European colonisation, flung out to the far end of the earth and trapped trying to contend with a land indigenous peoples had spent thousands upon thousands of years adapting to it and delicately adapting it in turn, building a modern country that has primeval roots but is also a tide pool of the world’s competing cultures, nestled between west and east and dogmas abroad in the world. George Miller’s Mad Max movies have always encompassed that experience in their metaphorical layers better than any historical film could ever approximate. Born the son of two Greek immigrants in Queensland in 1945, Miller’s industrious intelligence eventually gained him a private school education before attending the University of New South Wales as a medical student. In 1971, whilst in his last year of training in a residency at Sydney’s St. Vincent’s Hospital, Miller and his younger brother Chris made a one-minute-long short film, St. Vincent’s Revue Film, and he began dabbling more energetically in his moviemaking hobby whilst spending his working days dealing often with victims of terrible road accidents, the by-products of the country’s burgeoning passion for highway voyaging and speedy thrills.

At a film workshop Miller met Byron Kennedy, who would become Miller’s stalwart production partner and friend: the two men loaned their names to the production company they founded shortly after. Miller made experimental shorts and eventually the sardonic, satiric pseudo-documentary Violence in Cinema: Part 1 (1971), a work that made an impact with festival screenings and garnered several awards. Plainly, Miller’s destiny lay not in the A&E Ward but in movies, but it took another eight years before he got his feature directing career off the ground with Mad Max. Miller had developed the screenplay with James McCausland, a former finance editor of a major newspaper who had never written a script before, trying to forge something that could serve as a solid basis for the strange fantasy aesthetic Miller wanted to animate – action cinema, but drawing on silent comedy works by the likes of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, and set in a vaguely futuristic dystopian world to justify the kind of wild, semi-farcical rampages he was envisioning, coloured by a morbid fascination for the carnage he was so practically schooled in.

Miller wasn’t the first Australian filmmaker to tackle the nation’s car obsession and its correlation with the country’s uneasy feel for its place in the world and fascination with existence on the unruly fringe. Peter Weir had made his debut with The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), which similarly envisioned bizarre, quasi-science fiction visions of monstrous vehicles unleashed on an outback Australian town, and Sandy Harbutt had a cult success with Stone (1975), a study of a countercultural biker cadre but focusing on an undercover cop who learns to live and die by their curious code. Australian cinema culture, which had been enterprising if shaky both in finances and aesthetics since the medium’s earliest days, virtually died with the coming of television, but suddenly exploded to international prominence in the early 1970s. As this success unfolded a debate emerged, pitting those who wanted to foster artistic quality and ambition – represented in evergreen fashion by Weir’s Picnic At Hanging Rock (1975) and other signal hits of the Aussie New Wave – versus those who argued it needed a virile genre film scene to actually, properly sustain itself. The urge to propagate the latter led to the spasm of eccentric spins on standard fare today often referred to as Ozploitation – an argument that still essentially defines the national cinema in all its perpetually spasmodic persistence. Brian Trenchard-Smith’s The Man From Hong Kong (1975) had unexpectedly opened the gates for international success for Aussie films with a genre bent, assimilating and freely blending tropes from both the burgeoning kung fun movie and Hollywood thriller styles.

Miller perhaps came closest to making the schism vanish, as Mad Max was undoubtedly the product of a superior filmmaking talent and a particular vision, and also one that courted, and gained, a popular audience: the film took in over $5 million at the local box office, easily recouping its $400,000 budget, and some accounts have it bringing in over $100 million when released internationally. Mad Max came out at a propitious moment. The classic venues for low-budget genre movies, grindhouse movie theatres and drive-ins, were just about to be supplanted by the oncoming age of home video, and the first two Mad Max movies were ideal stuff to bridge the gap. My father told me the first movie he ever saw on video was of course Mad Max, being screened in a Sydney pub – perhaps the closest thing to the film’s natural habitat. Mad Max was sold to AIP for US distribution, but had to weather the indignity of having American voices dubbed over the Australian actors, in part to mitigate the film’s very Aussie lingo. Mad Max nonetheless offered a practically fool-proof blueprint for other moviemakers to produce their own hard-driving neo-barbarian action flicks: soon imitations were being turned out everywhere, from those well-schooled in capitalising, like Italy (Enzo G. Castellari’s Warriors of the Wasteland, 1983), to the Hollywood-financed, New Zealand-shot (Harley Cockliss’s Battletruck, 1982), and eventually megabudget blockbusters (Kevin Reynolds’ Waterworld, 1996), and latter-day homages like Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof (2007) and Neil Marshall’s Doomsday (2008).

Not that the Mad Max films lacked their own greedily harvested influences and imminent precursors. 1970s science fiction cinema had been littered with dystopian portraits of near futures riven with social breakdown brought about by metastasising trends of modern society from overpopulation to nuclear war to exhausted natural resources. Most immediately similar were the likes of Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (1975), which also offered thundering vehicles in a future dystopia, although Miller’s approach proved quite different to Bartel’s even in plying a similarly cartoonish, pop-art-inflected style. Mad Max’s title and basic premise of a cop pushed to extreme measures by lowlifes paid immediate, semi-satiric homage to Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971), and indeed the first film’s plot can be described as a fantastically filtered version of Harry Callahan’s backstory, and also nods to Death Wish (1974) in portraying a vigilante hero avenging assaulted family. Miller also paid increasingly pointed homage to Sergio Leone through his three original Mad Max films, and for what was then at least a more officially elevated sensibility, much tribute to John Ford and Akira Kurosawa. Joseph Losey’s The Damned (1963) was perhaps the first film to connect the post-war phenomenon of violent youth gangs and the new, omnipresent dread of the nuclear age informing a lurch towards neo-barbarianism, although Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) is likely the more immediate influence. Miller may also have cherry-picked and amplified the spectacle of familiar consumerist objects becoming items of future reveries glimpsed in Planet of the Apes (1968) and its sequels. The blend of the post-apocalyptic and action rampaging in The Omega Man (1971) was also a forebear, as was the future gladiatorial frenzies of Rollerball (1975), as well as the likes of Cornel Wilde’s No Blade Of Grass (1970), Robert Clouse’s The Ultimate Warrior (1975), John Carpenter’s Assault On Precinct 13 (1976), Jack Smight’s Damnation Alley (1977), and the last act of George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). And yet despite the obvious bricoleur nature of Mad Max, the film emerged as something original, even unique in tone and texture.

The appeal of the Mad Max films lay most obviously in the way they offered hard, fast, disreputable thrills that harked back to the glory days of the Western, but with that genre’s presumptions about history and community inverted, celebrating not the incoming of civilisation in the wilderness but its retreat, and imbued what once moseyed along with a hard chrome gloss and high-octane propulsion. This kind of movie could service different varieties of macho fantasy, from being the lone pillar of morality and heroism, to darker dreams of raping, looting, pillaging, and tearing about the desert in leather chaps. Miller also found a uniquely cunning way of bridging the concerns of the post-counterculture era of the 1970s and its social presumptions with the oncoming era of blockbuster flash fit for the 1980s. Even if the films themselves, or at least the first two, seemed like products produced in reflexive resistance to the homogenising influence of the mainstream precepts of the oncoming style, they were nonetheless essentially products of a similar sensibility to the one that created Star Wars (1977), not just in being preoccupied with narrative propulsion matched to delight in more literal speed and machinery, but in their boiled-down, would-be mythic narrative approaches (both series took significant inspiration from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces) and their deliberately pop art-like deployment of a self-consciously retro style, particularly apparent in their music scores with their soaring, romantic-melodramatic cues. Miller had an agonising time completing the film, actually quitting the shoot at one point and losing the respect of his crew, and yet it’s hard to believe given the movie as pieced together seems so utterly assured, the product of a cinematic prodigy.

On a parochial level, Mad Max captured the zeitgeist of an Australian culture of a very specific moment, and found a way of making different precincts of it talk to each-other – suburban “rev-heads” for whom the automobile was all but an object of religious fervour, thrown in with inner city punks and bikies. Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior would add into the mix S&M freaks and leather daddies out of a burgeoning queer scene, albeit with the sarcastic purpose of constructing an almost post-sexual society where all the sensual energy and bristling muscle is turned towards violent contest and even the women are pretty macho. All conversed on a level of cultural memory sourced in the nation’s harsh and grasping colonial era: Australia was well-equipped to meet any future collapse of civilisation because civilisation, in the modern sense at least, was still a work in progress here. Miller took up the common belief espoused in a lot of ‘70s culture that social decline and collapse was imminent, whether from a left-wing viewpoint as the result of nuclear war or environmental damage, or the reactionary conviction that the liberation ethos had unleashed only increasingly wild and strange gangs of hooligans and emblazoned identities insidiously wielded in a fracturing body politic, particularly strong when the punks supplanted the hippies as the subculture of choice to embody mainstream anxiety. Such ideas had permeated movies like A Clockwork Orange and Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979) and Nigel Kneale’s final, desolate Quatermass series, both of which emerged in the same year as the first Mad Max. The kind of raw and crazed behaviour that would define the age of the neo-barbarian would in turn spark increasingly fascistic and authoritarian responses, giving birth to new types of antihero from Harry Callahan to Travis Bickle and the comic book figure Judge Dredd, and Max himself, characterised initially as a future type of highway patrol cop as a member of the Main Force Patrol or MFP, or a ‘Bronze’ as the proliferating breed of highway berserker they regularly battle call them.

The peculiar world Miller and McCausland sketch out in Mad Max isn’t the desolate, post-apocalyptic landscape that the series would eventually become synonymous with, but rather a more familiar world where everything seems slightly estranged, heightened, sometimes edging towards the comic book, riven with decay and intimations of dark forces at loose in the world: a title simply states, “A few years from now…” The headlong force and pace of Miller’s style is immediately evinced in the first few shots, opening with a vision of the “Halls of Justice”, before shifting with a system of dissolves to a length of road littered with wreckage, another painted with a skull and crossbones, and then a shot of an MFP cruiser parked on the roadside of a stark stretch of highway with a looming sign pointing to “Anarchie Road – 3 km”. Immediately Miller orientates the viewer to his near-future as a place of decay and ambattled law and order: the Halls of Justice, which serve as the headquarters of the MFP, split the difference between citadel and Victorian workhouse, the letter ‘U’ in Justice hanging askew on the sign and foliage starting to weave around the gate, immediately signalling the decaying order of this world. The roads are established as dangerous regions and full-blown anarchy is just up the way. We’re immediately situated in a vaguely surreal culture where the law has become the besieged and society has been fragmented in blocs, touched with an abstracted, almost cartoonish directness.

All this information is conveyed in 10 seconds of screen time. And it’s not just the quickness of the shots that thrusts the viewer immediately into an off-kilter new reality, but Miller’s investment of motion even into these functional establishing shots, invested with a hypertrophied intensity by the zooms and tracking and wide-angled lensing in the anamorphic frame. Hints dropped throughout Mad Max that industrial society is on the way out, particularly in the way a V8 ‘Pursuit Special’ Interceptor is presented as the last of a kind, a pinnacle of mechanical achievement that won’t be seen again, and is pieced together by the worshipful repairmen who maintain the MFP’s vehicles. The Interceptor (actually a souped up Ford Falcon) is offered specifically to Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson), the star of the MFP’s dwindling ranks, by their commander, Captain Fred ‘Fifi’ Macaffee (Roger Ward) and Police Commissioner Labatouche (Jonathan Hardy) as a lure to keep him in their ranks. Fifi, who despite his nickname is a towering, muscular, shaven-headed he-man, in particular believes Max can be something the force, and the world, desperately need even if they don’t realise it – a hero. Mad Max’s lengthy opening sequence immediately galvanises the entire proposition, hurling viewer into the midst of a high-speed chase as the Bronzes chase down a fugitive criminal, known as ‘The Nightrider’ (Vincent Gil), a sweaty, leering hooligan who, in the company of his lover (Lulu Pinkus), has stolen one of the MFP’s pursuit vehicles after shooting a rookie cop, and the pair are careening down the highway on a lunatic joyride that feels close to some sort of religious rite – a first intimation of a concept that would recur through the series and its late extension entry Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), where the denizens of this world have attached not just their lifestyles to the roadraging but their theology too, seeking apotheosis and transcendence in the prospect of great speed followed by a sudden stop. “I am The Nightrider,” the hoon declares, “I’m a fuel-injected suicide machine!”

A roadside sign notes that there have been 57 deaths on this stretch of Highway 9 over the year, and some wag has erased the ‘O’ in Force and rechristened the MFP as the Main Farce Patrol. Two bored MFP officers lingering on the road are stirred to try and intercept, distracting one, Roop (Steve Millichamp) from the pleasures of spying on couples copulating off the roadside, whilst the other, Charlie (John Ley), reacts with offence when Roop blasphemes (“I don’t have to work with a blasphemer.”), but eagerly roars off to chase down The Nightrider, with Roop making no bones about his delight at the prospect of taking out their quarry with a blast of his shotgun. Two more MFP officers, Sarse (Stephen Clark) and Scuttle (George Novak), are directly pursuing The Nightrider, who manages to evade Roop and Charlie’s attempt to ram him. Motorcyclist patrolman Jim ‘Goose’ Rains (Steve Bisley) joins the chase from a diner, but all three pursuers crash when The Nightrider charges with mad zeal past a toddler stumbling across the road and then a car with a caravan, whilst Roop and Charlie crash headlong through the caravan, Sarse and Scuttle finish up flipping their vehicle, and Goose slams his bike against a car. Only Max, who’s been alerted to the chase, stands between The Nightrider and escape. Miller offers oblique and curtailed glimpses of Max donning his black leather MFP uniform and gear and revving up his pursuit car, his aviator sunglasses as chitinous armour, his car exhaust throbbing with suppressed power.

A classically momentous heroic build-up signalling Max’s stature as the MFP’s front-rank warrior, the man born to do battle on the road with such reprobates. But he’s not seen properly until after he chases down The Nightrider, who, distraught at being outdone by Max in a duel of chicken, then slams into a stricken truck, him and his moll finding their Valhalla in a bloom of orange flame. Then Miller fully unveils Max in the form of the young Gibson, jumping out of his car and beholding the spectacle with shock, demonstrating at least that such events still have an impact on him. Miller dissolves to Max at home, delivering another of his oddball touches of humour and characterisation entwined as Max relaxes with his young son and listens to his wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel) blowing a hot blues number on her saxophone. A delightful moment that seems chiefly to be a kind of diegetic lampoon of the common lyrical manner of depicting ideal romantic liaisons, often scored in days of yore with sultry sax sounds, but also a moment that sets up a peculiar motif in the movie – later Goose is impressed with a leggy cabaret singer (Robina Chaffey) he watches perform and later sleeps with, with Miller using this musical motif to literally present the women in the cops’ lives as performing an alternative to their bruising macho occupation. Max and Jessie’s relationship is quickly but effectively sketched, as Jessie registers her melancholy at the prospect of seeing Max off to another potentially fatal day at work, but also engages in their private language of humour as she deploys sign language to tell Max “I’m crazy about you,” a gesture he repeats to her later.

The clash of two peculiar subcultures preoccupies much of Mad Max’s first half – the MFP and a biker gang led by a florid, fearsome, Charles Manson-esque captain known by the memorable sobriquet of The Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Burn), who leads his cadre of brutes on bikes out into the boondocks to stir up trouble and attract MFP attention. Fifi tells Max, as they overlook one of the scenes of awesome road carnage that’s part and parcel of their job, that the word has gone out the The Nighrider’s pals want revenge for his fiery end. The gang arrives in the small town of New Jerusalem where The Nightrider’s remains have been brought in a small coffin. The gang sets about terrorising the locals, eventually chasing down a hapless couple (Hunter Gibb and Kim Sullivan) in a vintage Chevy and running them off the road: the gang takes delight in pulverising the car to pieces before raping both of them. Max and Goose, on patrol when reports of the disturbance come in, see the man fleeing across a field pantsless, ignoring the entreaties to stop, and then come to the wrecked car, where the find the woman distraught and leashed whilst a young member of the gang, Johnny (Tim Burns), lolls nearby, out of his head on drugs and unable to flee the scene.

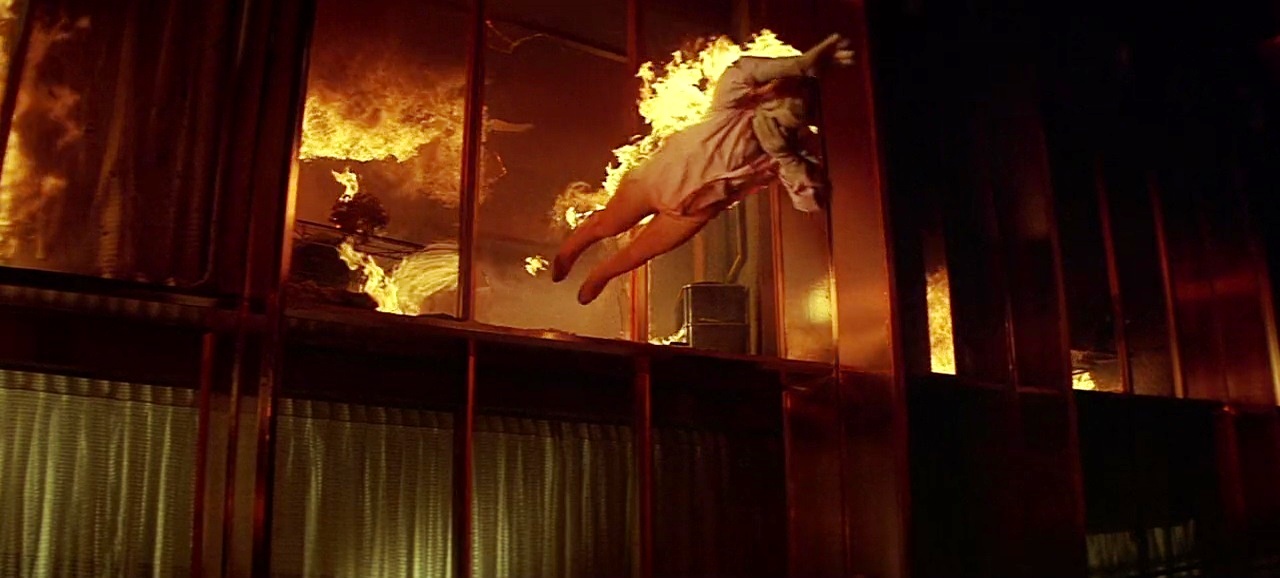

Johnny is taken to the Halls of Justice. Goose, who babysits Johnny whilst Max and Fifi attend the court hearing for his arraignment, is stirred to wild rage when they return with some bureaucrats and release Johnny because no witnesses showed up out of fear of the rest of the gang. In his anger Goose almost punches some of the officials and does manage to get in a good blow to Johnny after tackling him. Johnny rejoins the gang, who gather on a beach, with The Toecutter using a mixture of vaguely homoerotic intimidation and careful corralling of his men’s violent tendencies towards their ultimate goal of revenge. Johnny sabotages Goose’s patrol cycle whilst he’s watching the performance of the singer. The next morning Goose climbs aboard and rides off to work: he crashes as Johnny intended, but emerges uninjured and takes off in the truck that comes to fetch him and his bike. The bikers gang waits in ambush for him, however, with Johnny throwing a wheel at the windscreen of the truck, and this time Goose crashes off the road and is trapped in the truck. The Toecutter terrorises Johnny into setting fire to the crashed vehicle with Goose inside, and later Max is called to a hospital where he’s appalled by the sight of Goose, still alive but burned horribly: “That thing in there ain’t Goose,” Max declares to Fifi and storms off the job.

Miller takes a truism about the similarities of cops and criminals to an extreme throughout the film – both the MFP and the gang are comprised of oddballs, many with a penchant for violence and velocity and an antisocial streak counting themselves above the peasantry. Goose regales a fellow diner patron when first introduced by relishing the gruesome details regarding a crashed driver who was “sittin’ there tryin’a scream with his face ripped off.” The opening chase portrays the MFP goons and their marauding quarry as both delighting in the chance to wreak some carnage, only with one side slightly corralled and focused by the aim of the job. Both gangs have physically imposing and charismatic leaders with espousing personal ideals, although where The Toecutter espouses the lawless freedom and might-is-right prerogative – “Anything you say,” says the intimidated New Jerusalem Station Master (Reg Evans), to The Toecutter’s beaming reply, “I like that philosophy.” – Fifi wants to give the people heroes to believe in once more, one possible curative for the collapse of the world. In this aim Fifi is Miller’s ironic projection, as that’s what Mad Max as a movie also aims to do, albeit in a sour, ironic fashion still touched with a hues of the 1970s antihero ethos. Max isn’t just the best of the MFP but the most mature and grounded, but this also makes him vulnerable. The Halls of Justice interior proves as dilapidated as the outside, with offices trashed and stripped, a picture of a Queen Elizabeth hanging crooked as paltry remnant of a falling order. Meanwhile the bikers take pot shots at mannequins and drag random victims along the road behind their bikes.

With Mad Max Miller helped establish the rarefied quality many would note about the Australian genre film style with the emphasis on stylised, overlarge, borderline cartoonish performances around the margins pushing towards a brand of comedy bordering if usually never quite fully becoming satirical, a tendency exemplified elsewhere by the likes of Russell Mulcahy’s Razorback (1983). Miller was more controlled than any of his fellows in deploying this element throughout the first three Mad Max films, however, as he contrasts the craziness of the world around Max with his increasingly taciturn demeanour and air of wounded and affected expedience persisting around the heart of an eternal knight, as if consciously playing off the classical hero’s stature against a profane setting inhabited by humans devolving back towards the simian. Keays-Burn’s performance as The Toecutter mediates the two extremes, an edge of prissy, theatrical showmanship simmering under the bristling physical intimidation and berserker affectations, delighting in such gestures of charged intimacy as thrusting a shotgun muzzle into Johnny ’s mouth or, in a teasing reversal, obliging Jessie to let him lick the ice cream she’s bought for her son. Throughout the film Miller uses birds as emblems often punctuating scenes of violence as he dives in for visions of their leering, cawing beaks and flapping wings, and sometimes pecking on the human roadkill.

The fetishism of masculinity throughout the Mad Max films is one of their amusing and weirdly vital aspects: the first film revolves around the extermination of the feminine aspect of life, as Goose is cooked after sex and Max ruthlessly stripped of his family life as precursors to the loss of civilisation itself. Any hint of erotic connection is virtually exiled from the equation in the follow-ups, and only starts to return either in a pubescent form or in the shape of an imperious antagonist (Tina Turner’s Aunty Entity) who at once plays up and subverts an affectation glamorous femininity (with her chainmail mockery of a showgirl costume) by the end of the third movie. The homoerotic aspect of the series is barely concealed, and some have even argued the first film is a fundamentally a portrait of a man surrendering to his secret queerness as the underbelly of the theme of loss and abandonment to wrath and ruin. Either way it’s knowingly sourced in, and also simultaneously making fun of, the macho precincts of Australian culture back in the day, reducing it to a lunatic caricature of itself and prodding the rhetorically vast but in practice tiny gap between that culture and the kind of camp that was verboten. The Toecutter’s grip on his men, particularly young Johnny , is laced with shows of seductive intimacy, although it’s more indicative of his contempt for any kind of polite society and a preparation for a rapidly oncoming future where the will to fuck and the fate of being fucked will become markers of power rather events of reproductive purpose, leading to the second film’s survey of “gayboy berserkers” on the warpath.

Whatever can be said about Gibson’s later successes and sins, his rise, downfall, and partial rise again, he was an inextricable aspect of the Mad Max series’ success, just as the series was for him. Any number of jut-jawed, hard-bodied young actors might have been cast, but Gibson, as a serious, classically-trained actor as well as a born movie idol, had something more. After establishing himself as a student at the National Institute of Dramatic Art and theatrical work including stints as a Shakespearean, Gibson had made his debut in the surfing flick Summer City (1977) and appeared as romantic young co-lead in Tim (1979) in the same year Mad Max emerged. Max isn’t a demanding part in the dramatic sense – he has a grand total of sixteen lines in first sequel – and yet demanded commitment, the capacity to inhabit a role and charge the screen through that presence, and Max inscribed the basic star persona Gibson would present variations on in movies like Lethal Weapon (1987), Braveheart (1995), The Patriot (2000), and even Hamlet (1990) – protagonists with something berserk lurking under the strained surfaces of civilised poise they try desperately to maintain. The Max we’re introduced to in the first film is riven with hints of something unstable and potentially maniacal registering in the glassy glare and kinescopic flicker of his eyes, even before Max Rockatansky officially goes mad. But Gibson’s youthful charm and quality of innocence are key to the first film as well, traits still persisting despite his experiences on the job, and emerging most properly when he talks about his father with his wife, signalling another path towards purgation beckoning to him.

The second half of Mad Max turns away from the theme of embattled institutions towards the more imminent threat of The Toecutter and his gang to Max, Jessie, and son Sprog (Brendan Heath) after Max quits the MFP and travels to the coast to try and knit his damaged soul and psyche together, which seems to start working as along the way Max confesses his vulnerabilities to Jessie. But the seaside locale they’ve come to proves, by way of extremely bad luck, to be the same place where The Toecutter and gang hang out. Jessie, after smiling her way through The Toecutter’s queasy come-ons, gets in a display of her own surprising pith as she shoves an ice cream in his face and knees him in the groin before fleeing, only later to find that the severed hand of one of the gang members is dangling from off the back, wrapped in the chain he tried to lash their wagon with. Later, the family camp out on the farm of old friend May Swaisey (Sheila Florence, an elderly stalwart who also notably appeared on the cult TV series Prisoner, aka Cell Block H), who lives with her intellectually disabled son Benno (Max Fairchild). After a stroll down to swim and sunbathe at a nearby beach, Jessie becomes unnerved by menacing figures darting through the forest on the way back, as well as the looming presence of Benno. Whilst Max descends into the forest whilst Jessie returns to the farm, only to be confronted there by the gang. May unveils her unexpected fortitude by facing down the gang with her shotgun, giving her, Jessie, and Sprog time to flee in the wagon, only to find the vehicle has been sabotaged and breaks down. Whilst May shoots at the gang, who blaze by unconcerned, Jessie runs down the highway with her baby, only to be casually run down and killed.

In this portion Miller veers into horror movie-like territory, echoing other hit ‘70s films like Straw Dogs (1971) and Last House On The Left (1972) as well as the likes of Death Wish (1974) as the narrative shifts towards the theme of A Man Pushed Too Far, whilst the style turns from open road stunts to more sustained suspense-mongering, particularly apparent in Miller’s expert staging of Jessie’s stalking in the forest, a little masterpiece of controlled perspective and fleeting menace. His capacity to wield exploitation movie zeal is confirmed in the sight of the gnarled severed hand dangling from the family wagon, but shift to a more judicious but also more effective and dramatically forceful approach, as he conveys Jessie and Sprog’s deaths through the most minimal of means, noting only a baby shoe and ball bouncing in the wake of the fleeing bikers upon the vast flat tarmac. The sight of May wielding a gun nearly as big as she is and blasting it off with warrior pith signals Miller’s penchant for unexpected, semi-comic disparities and is also an early sign of the increasing delight in tough females he would deploy in the sequels. In Mad Max however Jessie and Sprog’s deaths are the necessary blood sacrifice in Fifi and Miller’s shared aim of transforming Max from man to hero, a transformation that also destroys Max the man. At least, that’s how the series would play out – in the first film at least Jessie’s fate is left ambiguous as two doctors talk about her terrible injuries but also confirm that she’s still alive, whilst Sprog’s death is confirmed. Miller performs a deft little camera move from the medicos talking about it to reveal Max concealed by the doorway to the hospital ward listening to it all, blue eyes wide and haunted.

Max returns to his home, fishes his uniform leathers out of a trunk, and heads to the MFP garage to fetch his black-painted chrome steed, the as-yet untested V8 Interceptor, and heads out onto the roads to chase down The Toecutter and his gang in the prototypical roaring rampage of revenge: first he visits and brutalises a mechanic who does business with the gang, and rattles The Toecutter’s cage by leaving polaroid photos of his family and Goose on his bike, so he know what’s coming and why. The climax is structured in a way that plays havoc in its own particular way with the familiar rhythm of an action climax, however. Max lies in ambush for some of the gang as they steal fuel from a moving tanker – a brief vignette that nonetheless lays seeds for both the motion gymnastics of Fury Road and also the Fast and Furious films – and lures them into chasing him before turning and charging through the ranks of bikers with the Interceptor on a narrow bridge, leaving many sprawled and broken on the road, others launched off a bridge into a river. Johnny survives, having been left behind, and he rings up The Toecutter to warn him. The Toecutter and others set up an ambush in turn for Max: The Toecutter shoots Max in the leg and runs over his arm with his bike, but Max’s determination still gets him back behind the wheel of the Interceptor, and he chases down The Toecutter.

Miller’s sublimation of cartoonish effect hits most mischievously and memorably as he dives in for ultra-close shots of The Toecutter as he suddenly rides over a rise in front of an upcoming truck, the villain’s eyes bulging from their sockets Tex Avery-style a split-second before the truck hits The Toecutter’s bike and smashes it to oblivion, the truck’s wheels riding over his mangled body for special relish. Johnny’s comeuppance comes in a coda that plays out as a peculiar dramatic and emotional diminuendo, as Max comes across him scavenging on a car wreck, handcuffs his leg to the wreck, and leaves him with the alternative of burning to death or sawing his foot off (a touch that in itself lays seeds for a much later, popular genre creation by Australian filmmakers, the Saw series). The car explodes in the background as Max drives away. Johnny’s fate is then left ambiguous, as it’s rather Max’s that Miller finds an original and perturbing way of describing. Far from offering any kind of catharsis, Miller instead offers the sight of Max glaring dead-eyed out from behind the wheel of his car as he drives out into the endless flatness of the outback and regions marked by signs as forbidden for some reason – perhaps polluted or irradiated, perhaps meant to recall the Forbidden Zone of Planet of the Apes but also calling to mind the cordoned-off areas of the Australian outback where atomic bomb tests were carried out. Except that in the Mad Max mythos this becomes the place of sanctuary, the last resort of survivors of an oncoming armageddon. Miller might have had sequels in mind already, but the final note of Mad Max is unique in its forlorn prospect, the resolution defined by the very absence of familiar resolution. Slow dissolve to the endless black tar and broken white lines before Max, like reels of code comprising his new programming as the relentless wanderer, looking for some new stage to unleash his bloody talents upon — but perhaps to recover his humanity too.