.

Director / Screenwriter: Jean-Luc Godard

In memoriam: Jean-Luc Godard 1930-2022

By Roderick Heath

In 1967, cinema ended. Whatever has been flickering upon screens ever since might perhaps be likened to a beheaded chicken or a dinosaur whose nervous system still doesn’t know it’s dead even as it lurches around. At least, that’s what the title at the end of Jean-Luc Godard’s most infamous film declares – FIN DE CINEMA – as an attempted Götterdammerung for an age of both movies and Western society, as well as for Godard’s own life and career up to that moment. In eight years Godard had gone from being a fringe film critic to one of the most artistically respected and cultishly followed filmmakers alive. His marriage to actress Anna Karina had unexpectedly made him a tabloid star and inspired some of his most complete and expressive films. The union’s dissolution by contrast saw Godard driven into a frenzy of cinematic experimentation that started his drift away from his Nouvelle Vague fellows and off to a strange and remote planet of his own, defined by an increasingly angry and alienated tone. Godard’s relentless play with cinema form and function seemed to become inseparable from his own drift towards radical politics. Politically provocative from Le Petit Soldat (1960) on, Godard’s new faiths crystallised whilst making La Chinoise (1967), an initially satiric but increasingly earnest exploration of the new student left and its war on decaying establishments, which happened to coincide with him falling in love with one of his actors, Anne Wiazemsky, in what would prove another ill-fated marriage.

Godard found himself riding at a cultural vanguard, as young cineastes adored his films and considered them crucial expressions of the zeitgeist, and Godard in turn championed the radical cause that would famously crest in the enormous protest movement of 1968. Week End predated the most eruptive moments of the late 1960s but thoroughly predicted them. What helps keeps it alive still as one of the most radical bits of feature filmmaking ever made depends on Godard offering the rarest of experiences in cinema: an instance of an uncompromising artist-intellectual with perfect command over his medium making a grand gesture that’s also an auto-da-fe and epic tantrum, a self-conscious and considered repudiation of narrative cinema. Many critics in the years after the film’s release felt it was a work of purposeful self-destruction, not far removed from Yukio Mishima’s ritual suicide. Godard certainly did retreat to a creative fringe that of course thought of itself as the cultural navel of a worldwide revolutionary movement, making films in collaboration with other members of the filmmaking collective called the Dziga Vertov Group, and would only slowly and gnomically return to something like the mainstream in the 1980s. Godard’s aesthetic gestures, his violation of narrative form, and the conviction with which it anticipates the ever-imminent implosion of modern civilisation. Godard set out to attack many things he loved, not just film style but also women, art, cars – his alter ego in Le Petit Soldat had mentioned his love for American cars, but in Week End the car becomes a signifier of everything Godard felt was sick and doomed in the world.

Week End was the film Godard had been working to for most of the 1960s and all he made after it was a succession of aftershocks. It remains in my mind easily his greatest complete work, only really rivalled by the elegiac heartbreak of Contempt and the more pensively interior and essayistic, if no less radical 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967). It’s also a crazed one, an obnoxious one, laced with self-righteousness, self-loathing, confused romanticism, sexism, flashes of perfervid beauty, and violence that swings between Grand Guignol fakery and snuff movie literalness. Some of it has the quality of a brat giggling at his own bravery in pulling his dick out in church, other times like a grandfatherly academic trying to talk hip. All feeds into the maelstrom. Godard’s overt embrace of surrealism and allegory, with heavy nods to Luis Buñuel, particularly L’Age d’Or (1930) and The Exterminating Angel (1962), allowed him to ironically lance at the heart of the age. The vague basis for the film, transmitted to Godard through a film producer who mentioned the story without mentioning who came up with it, was a short story by the Latin American writer Julio Cortázar, whose work had also inspired Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966).

The plot of Week End, such as it is, presents as its rambling antiheroes the emblematic French bourgeois couple Corinne (Mireille Darc) and Roland (Jean Yanne), greedy, amoral, wanton, bullish creatures, hidden under a thin veneer of moneyed savoir faire: they might be total creeps but they dress well. Both are having affairs and plotting to murder their spouse. Both are meanwhile conspiring together to kill Corinne’s father, a wealthy man who owns the apartment building they live in, and is now finally sickening after the couple have spent years slowly poisoning him. But they’re worried he might die in hospital and Corinne’s mother might falsify a new will cutting them out, so need to reach the family home in Oinville. The couple linger around their apartment in expecting news: Corinne talks furtively on the balcony with their mutual friend, and her secret lover, whilst Roland does the same over the phone with his mistress. “I let him screw me sometimes so he thinks I still love him,” Corinne tells the lover as they converse on the balcony, whilst Corinne idly watches as the drivers of two cars down in the building car park clash. The driver of a mini accosts one a sports car for cutting him off. The fight quickly escalates into a fearsome beating, with one driver set upon by the other and his companion, and left in a bloodied sprawl by his vehicle.

A little later this vignette is algorithmically repeated with variance as Roland and Corinne also get into a battle in the car park, after Roland bumps their Facel-Vega convertible into a parked car. A boy playing in store-bought Indian costume shouts for his mother, as the hit car belongs to his parents. The mother berates the couple, quickly sparking a comic battle in which she fends off the infuriated Roland by swatting tennis balls at him whilst Roland fires paint from a water gun at her. Her husband bursts out of the building with a shotgun and fires, forcing Roland and Corinne to flee, whilst the boy cries after them, “Bastards! Shit-heap! Communists!” The diagnosis of some awful tension and rage lurking within the seemingly placid forms of modern consumer life is the first and perhaps the most lasting of Week End’s insights, anticipating epidemics of road rage and on to the flame wars and lifestyle barrages of online life. Things like cars and designer clothes as presented through Week End aren’t just simply indicted as illusory trash, but as treacherous things because they are presented as yardsticks of modern life, creating bubbles of identity, and when those bubbles of identity collide and prove to be permeable, the result stirs a kind of insanity.

Before they set out on their fateful odyssey to Oinville, Corinne goes out to spend a session with a therapist, or at least that seems to be the cover story for Corinne meeting her lover. In cynical pastiche of the analytic process – or “Anal-yse” as one of Godard’s title cards announces – Corinne sits on a desk, in a near-dark office, stripped down to her underwear, with her lover playing therapist (or perhaps he really is one), his face in near-silhouette. Corinne begins a long, detailed monologue recounting sexual encounters with a lover named Paul and also Paul’s wife Monique, explaining her pornographic adventures with the pair that quickly progresses from lesbian fondling to dominance displays as Monique sat in a saucer of milk and ordered the other two to masturbate. Whether the story is real or not matter less than its ritualistic value in serving the game between Corinne and her “therapist,” who ends the game by drawing Corinne in for a clinch. The lurid flourishes of Corinne’s anecdote (drawn from surrealist erotica writer Georges Bataille, whose influence echoes throughout the film) mesmerise by describing sordid and perverse things Godard can’t possibly show in a mainstream movie, the first and most elaborate of his many uses of discursive and representative technique to avoid the merely literal.

Along with the titillation, challenge: nearly ten minutes long, this scene is one of several in Week End deliberately contrived to exasperate viewers with its seemingly pointless length and intense, unblinking technique. Darc has to hold the screen right through without a cut, with Godard’s regular cinematographer Raoul Coutard gently moving the camera back and forth in a kind of sex act itself. On the soundtrack random bursts of Antoine Duhamel’s droning, menacing score come and go, sometimes so loud as to drown out the speech: the music seems to promise some dark thriller in the offing, and keeps coming and going through the film. Satirical purpose is draped over it all, as Godard indicts secret roundelays of sexual indulgence played out in bourgeois parlours whilst official moral forms are maintained, as well as mocking movie representations of sex. On yet another level, the scene is an extension, even a kind of ultimate variation, of Godard’s penchant first displayed in Breathless during that film’s epic bedroom scene, for long, rambling explorations of people in their private, deshabille states.

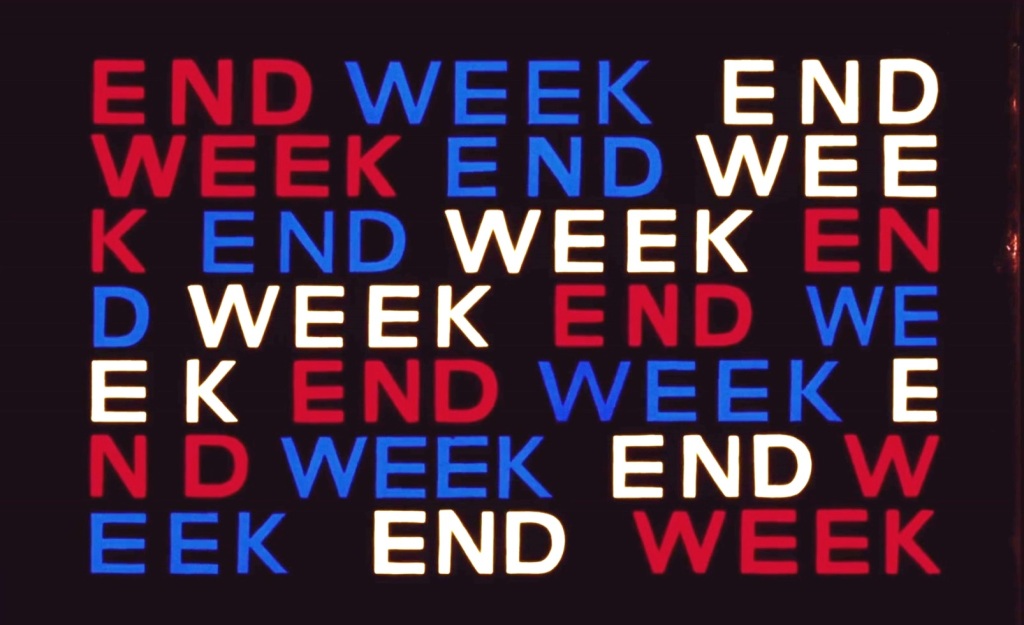

Godard’s signature title cards, with their placard-like fonts all in capitals save for the “i”s still sporting their stylus, have long been easy to reference by any filmmaker wanting to channel or pastiche the Godardian style, instantly conveying ‘60s radical chic. Godard had been using them for a while in his films, but it’s Weekend that wields them as a recurring device not just of scene grammar but aggressive cueing and miscuing of structure and intent. Week End is introduced as “a film found in a dustbin” and, later, “a film lost in the cosmos.” The titles declare the day and time as if obeying neat chronology, but begin to lose track, designating “A Week of Five Thursdays” and events of apparent importance like “September Massacre” and “Autumn Light” and devolving into staccato declarations of theme like “Taboo” and conveying cynical, indicting puns. At 10:00 on Saturday morning, as one title card informs us with assurance, Corinne and Roland set off on their unmerciful mission, surviving their encounter with the shotgun-wielding neighbour only to get caught in a massive traffic jam on a country road.

This sequence, nearly eight minutes long and setting a record at the time for the longest tracking shot yet created, contrasts the hermetic intensity and verbal dominance of the “Anal-yse” scene with an interlude of pure visual showmanship, perhaps the most famous and certainly the most elaborate of Godard’s career. It’s one that also takes to a logical extreme Andre Bazin’s cinema theories about long takes, transforming the movement of the camera and its unyielding gaze to enfold multivalent gags and social commentary. The shot follows the course of the jam as Roland tries with all his gall and ingenuity to weave his way along it. The air sings with endless blaring car horns amassed into an obnoxiously orchestral dun, as the Durands pass multifarious vignettes. An old man and a boy toss a ball back and forth between cars. Men play poker. An elderly couple has a chess match whilst sitting on the road. A family settled on the roadside, father reading a book and sharing a laugh with the rest. A white sports car rests the wrong way around and parked in tight between a huge Shell oil tanker and another sports car. Trucks with caged animals including lions, a llama, and monkeys which seem to be escaping. A farmer with a horse and cart surrounded by droppings. Roland almost crashes into the open door of a car, and Corinne geets out and slams the door shut with the choice words to the driver before resuming. On the roadside at intervals dead bodies are glimpsed near the broken and buckled remains of cars. Roland finally leaves the jam behind as police clear one wreck, and takes off up a side road.

The guiding joke of this scene sees most of humanity adapted and resigned to such straits. The price paid for the car, in both its functionality and its promise of release, has proven to be the screaming frustration of dysfunction and ironic immobility, punctuated by the horror of traffic accidents, and an enforced detachment, even numbness, in the face of a survey of gore and death. At the same time, comic pathos, scenes of ordinary life simply being lived in the transitory state of the road rather than in tight urban apartments, and the establishment of tentative community. Nascent, a primal hierarchy, as Roland and Corinne urge, bully, threaten, and steal bases along their path, mimicking their plans to circumvent waiting for their fortune: awful as they are, the couple are at least evolved to be apex predators in this pond. This sequence links off every which way in modern satire and dystopian regard, close to J.G. Ballard’s writing in its satiric, quasi-sci-fi hyperbole and anticipating Hollywood disaster movies of the next half-century, just as much of the film’s midsection lays down the psychic blueprint for generations of post-apocalyptic stories.

Weekend is a satire on the (1967) present and a diagnostic guess at the future, but also a depiction of the past. Visions of roadways clogged with traffic, roadside carnage, the tatty countryside infested with refugees, refuse, and resistance warriors, constantly refer back to the France of the World War II invasion and occupation, perhaps merely the most obvious and personal prism for Godard to conceive of societal collapse through, whilst also presenting the invasion as a mutant variation, infinitely nebulous and hard to battle. Week End starts off as a film noir narrative with its tale of domestic murder for profit, and remains one for most of its length, even as it swerves into a parody of war movies. It’s also an extended riff on narratives from Pilgrim’s Progress and Don Quixote to Alice In Wonderland and The Wizard Of Oz, any picaresque tale when the going gets weird and the weird turn pro, each encounter a new contending with the nature of life and being, the shape of reality, and the limits of existence. Comparisons are easy to make with Week End, because everything’s in there. The sense of time and reality entering a state of flux becomes more explicit as the Durands begin to encounter fictional characters and historical personages and new-age prophets, keeping to their overall motive all the while.

After escaping the traffic jam, Corinne and Roland enter a small town where they stop so Corinne can call the hospital her father is in, as they’ve fallen behind schedule and Corinne is fretting over any chance her father’s will can be changed at the last moment. As they park a farmer drives by in a tractor lustily singing “The Internationale,” and a few moments later the sound of a crash is heard, a fatal accident as the tractor hits a Triumph sports car, a sight Corinne and Roland barely pay attention to, and when they do it’s to fantasise it involved her father and mother. When Godard deigns to depict the crash, he slices the imagery up into a succession of colourful tableaux, the mangled corpse of the driver covered in obviously fake but feverishly red and startling blood, gore streaming down the windshield. The driver’s girlfriend can be overheard arguing with the tractor driver, before Godard show the two bellowing at each-other, the woman, covered in her lover’s blood, raving in a distraught and pathetic harangue as she accuses the tractor driver of killing him deliberately because he was a young, rich, good-looking man enjoying life’s pleasures: “You can’t stand us screwing on the Riviera, screwing at ski resorts…he had the right of way over fat ones, poor ones, old ones…” Worker and gadabout cast aspersions on each-other’s vehicles, and the girl wails, “The heir of the Robert factories gave it to because I screwed him!” All this Godard labels, with cold wit, “Les Lutte des Classes” (“The Class Struggle”).

As the pair argue, Godard cuts back to shots of onlookers seemingly beholding the scene but also posing for the camera, framed against advertising placards with bright colours and striking designs. Coutard captures the popping graphics and the faces of the witnesses, sometimes gawking in bewilderment, one trying to control the urge to laugh, and others ranked in stiff and solemn reckoning (including actress Bulle Ogier, who like several actors returns at the end as a guerrilla). The woman and the farmer dash over to Corinne and Roland to each solicit their support in reporting the accident their way, only for the couple to flee in their car: “You can’t just leave like that, we’re all brothers, as Marx said!” the farmer shouts, whilst the girl shrieks, “Jews! Dirty Jews!” Both left bereft and appalled, the farmer finishes up giving the woman in a consoling embrace, in the film’s funniest and most profoundly ironic depiction of the evanescence of human nature. Godard shifts to a vignette he labels “Fauxtography” as he now films the actors from the scene in group portrait against the ads, with a discordant version of “La Marseillaise” on the soundtrack, as if in pastiche of group photos of resistance members at the end of the war, and the way patriotism is often invoked as the levelling answer to the aforementioned class struggle.

Throughout Weekend Godard recapitulates elements of style explored in his previous films: the “Anal-yse” scene as noted recalls the explorations of human intimacy in his first few films, albeit hardened into distanced shtick, as the tractor crash scene recalls his more pop-art infused works of just a couple of years earlier like Pierrot le Fou (1965) and the fetishisation of the allure of marketing in Made in USA (1966). Vignettes later in the film, including Emily Bronte musing over the age of a stone and its pathos as an object untouched and unfashioned by humanity, and the Durands studying a worm squirming in mud, recall the intensely focused meditations on transient objects and sights explored in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her. The concluding scenes return to the children’s playtime approach to depicting war Godard had taken on Les Carabiniers (1963). Few directors, if any, had ever tried so hard to avoid raking over their old ground as Godard in the whirlwind of his 1960s output, and this systematic rehashing underlines the way Week End offers a summarising cap on his labours whilst also trying to leap beyond it all. Godard resisted suggestions his films were improvised, instead explaining that he often wrote his scenes just before filming, nonetheless seeming to grow them organically on the move, and so Week End is its own critique, a response to a moment and a response to the response.

As they roar on down the road, Roland comments when Corinne asks about the farmer’s plea, “It wasn’t Marx who said it. It was another Communist – Jesus said it.” As if by invocation, the couple soon encounter a son of God on the road, albeit not that one. In a jaggedly filmed interlude, the couple pass through another, seemingly even more hellish traffic jam, with Godard’s title cards violently breaking the scene up into hourly reports. This jam is glimpsed only in close-up on the couple as they engage in bellowing argument with other drivers who, out of their cars, grab and claw at them, obliging both to bit at hands and fingers, as Roland barks at another driver, “If I humped your wife and hurt her would you call that a scratch?” Resuming their journey again, this time through rain, the pair are flagged down by a woman hitchhiker, Marie-Madeleine (Virginie Vignon): Roland gets out and inspects her, lifting her skirt a little, before assenting to take her. The woman then calls out a man travelling with her (Daniel Pommereulle), hiding in a car wreck on the roadside: the frantic man, dressed in bohemian fashion and wielding a pistol he shoots off like a lion tamer, forces the Durands to take them back in the other direction.

The man explains after the rain stops and the top has been rolled back down that he is Joseph Balsamo, “the son of God and Alexandra Dumas…God’s an old queer as everyone knows – he screwed Dumas and I’m the result.” This unlikely messiah explains his gospel: “I’m here to inform these modern times of the Grammatical Era’s end and the beginning of Flamboyance, especially in cinema.” That Joseph looks a little like Godard himself connects with the earnestness of this seemingly random and absurd pronouncement, as Joseph herald’s the film breakdown into arbitrary and surreal vignettes, and the texture of the movie itself losing shaoe, and Godard’s own imminent departure from mainstream filmmaking. It’s also a flourish of puckish self-satire, as Godard-as-Joseph wields the power of the camera and editing to manifest miracles and punish the wicked, whilst also paying the debt to Luis Bunuel’s arbitrary swerves into pseudo-religious weirdness as he labels this scene “L’Ange Ex Terminateur.” Joseph promises the Durands he will grant any wishes they want to make if they’ll drive him to London, and proves his statement by casually manifesting a rabbit in the glove compartment.

This cues an oft-quoted scene as the Durands muse on the things they want most: Roland’s wishes include a Miami Beach hotel and a squadron of Mirage fighters “like the yids used to thrash the wogs,” whilst Corinne longs to become a natural blonde and for a weekend with James Bond, a wish Roland signs off on too. Joseph, disgusted with such obnoxious wishes, refuses to ride with them any longer, but Corinne snatches his gun off him and tries to force him: the Durands chase the couple out of the car and into a field strewn with car wrecks, but Joseph finally raises his hands and transforms the wrecks into a flock of sheep, reclaiming his gun from the startled Corinne and thrashing the couple as they flee back to the car. Godard refuses to perform a match cut as Joseph works his miracle, instead letting his gesture and cry of “Silence!” repeat, making crude technique into a performance in itself, claiming authorship of the editing miracle and breaking up screen time.

Godard had always exhibited an approach to filmmaking akin to trying to reinvent it from shot to shot even whilst assimilating myriad influences, but Week End as seen here engages directly with the notion of treating the film itself as a kind of artefact, with seemingly random, amateurish, but actually highly deliberated, assaults on the usually ordered progress of a movie. Godard reported that he took inspiration for Corinne’s orgy monologue from Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), but it feels likely he also found permission in the Bergman film’s opening and closing glimpses of the film itself starting to spool and finally burning out, to take the notion much further and attack the very idea of linear coherence as proof of professional assembly in cinema. One ostentatious example later in the film sees a scene toggle back and forth from “Sunday” to “Story For Monday,” with a brief shot of Yanne-as-Roland singing as he walks down the roadside shown three times, like the scene’s been hurriedly spliced together by a high schooler, signalling the further fracturing of time in the Durands’ odyssey. Some of these touches quickly became emblematic clichés of the era’s would-be revolutionary cinema, at once heralded by simpatico minds and derided by others.

More immediately, Godard uses the impression of movie breakdown to illustrate another kind. After fleeing Joseph, the Durands tear down the road, Roland so frustrated and aggressive he causes bicyclists and cars alike to swerve off the road, until he crashes himself in a fiery pile-up with two other cars. Godard makes it seems as the film is sticking and flickering, eventually caught with the frame edge halfway up the screen, as if hitting an amateurish splice point. This delivers the impression of the crash, its awfulness a wrench in the shape of reality, whilst allowing Godard to avoid having to actually stage it, and placing the illusion of the film itself in the spotlight, dovetailing Godard’s aesthetic and dramatic intentions in a perfect unity. This inspiration here feels more like Buster Keaton’s games with cinema form in Sherlock Jr (1924), the frame becoming treacherous and malleable, characters and story getting lost in the spaces between. The crash also cues the film’s most famously cynical gag. The wreck is a scene of total chaos, a passenger tumbling out of a burning car writhing in flames, Roland himself squirming out of the capsized Facel-Vega all bloodied and battered. Corinne stands by, screaming in bottomless horror and woe, finally shrieking “My bag – my Hermés handbag!”, as the designer item goes up in smoke.

Surviving relatively unscathed, the couple start down the road on foot, still seeking the way to Oinville, or someone who will give them a lift. But the country proves an increasingly unstable and dangerous space as the couple stroll by an increasing numbers of car wrecks, corpses littering the road: trying to get directions from some of the splayed bodies, Roland eventually concludes, “These jerks are all dead.” Corinne spies a pair of designer trousers on one corpse and tries to steal it, only forestalled when a truck comes along and Roland has Corinne lie on the road with her legs splayed as a hitchhiker’s tactic, one step beyond It Happened One Night (1934). At another point on the road, the tiring pair settle on the roadside, Corinne taking a nap in a ditch whilst Roland tries to thumb a ride. A tramp passes by, sees Corinne in the ditch, and after alerting Roland to the presence of a woman there to Roland’s total disinterest, the tramp descends to rape her. Meanwhile Roland keeps flagging down cars for a lift only to be asked gatekeeping questions like, “Are you in a film or reality?” and “Who would you rather be fucked by, Mao or Johnson?”, Roland’s answers apparently wrong as the drivers speed off leaving them stranded. As Corinne crawls out of the ditch, Duhamel drops in a flourish of stereotypically jaunty French music as if to place a sitcom sting on her assault.

The evil humour here and elsewhere in Week End does provoke awareness of Godard’s often less than chivalrous attitudes to women at this point in his art. He told Darc when they first met for the film that he didn’t like her or the roles she played in films, and a cast member felt Godard relished a scene where the actor had to slap Darc, but cast her anyway to be the ideal emblem of everything he hated. The identification of the bourgeois society Godard was starting to loathe so much with femininity is hard to ignore, even if it is intended to be taken on a symbolic level. Of course, Week End is primarily the spectacle of an artist emptying out the sluice grate of his mind, come what may, and this vignette, playing ugliness as a casual joke, also captures something legitimate about the state of survival, as if Corinne and Roland are by this time two hapless refugees on the road of life, the dissolution of any semblance of safety befalling this prototypical pair of wanderers, although the film signals they are still perfectly armour-plated by their arrogance and obliviousness, and their own hyperbolic readiness to use violence and murder to achieve their own ends as representatives of the exploitive side of Western capitalism. “I bet mother has written us out of the will by now,” Corinne groans as she tries to purloin those designer pants, to Roland’s retort, “A little torture will change her mind. I remember a few tricks from when I was a lieutenant in Algeria.”

Earlier in the course of their wanderings, the pair also muse over their plans for killing whilst strolling by an incarnation of Louis de Saint-Just (Jean-Pierre Leaud), a major figure of the French Revolution, reciting his political tract “L’esprit de la Révolution et de la Constitution de la France,” with his passionate denunciation of the constant risk to liberty and fair governance from human fecklessness and greed. As well as the blatant contrast with the duo discussing murder for profit behind Saint-Just, Godard implies the link between the glorious revolutionary spirit of the past and the modern radical spirit, like turns to Marxist-hued revolution in the Third World, as espoused in a length scene late in the film in which Godard has two immigrant garbage collectors, one Arab (László Szabó), the other African (Omar Diop). The two men lecture the audience in droning fashion about current revolutionary turns in their respective homelands. Throughout Week End Godard makes a constant attempt to adapt into cinematic language playwright Berthold Brecht’s famous alienation techniques from the stage. Such techniques were intended to foster detachment from mere dramatic flow and oblige the audience to think about the ideas being expressed to them, in the opposite manner to the goal of most dramatic creations to weave such things together. The many formal and artifice-revealing tricks in the movie are wielded to that end, perhaps presented most bluntly when Godard has each garbage man gets the other to speak out his thoughts whilst Godard holds the camera on the face of the silent man as they eat their lunch: the directness of the political speech is amplified by not seeing it spoken. During their speech Godard drops in flash cuts to earlier moments in the film, including of Saint-Just speaking, but also of the cart loaded with horse manure – the continuum of history, or just the same old shit?

Amongst the many facets of his filmmaking that made an enormous impression from his debut Breathless (1960) on, Godard’s ardent belief that the history of cinema was as worthy as literature and music of being referenced and used as the basis of an artistic argot had been a salient one: where an author would readily be congratulated for including allusions to and quotes from other texts, there is still anxiety in many cineastes over whether that is in movies just ripping off, or the equivalent of a kind of secret handshake between film snobs. Godard happily indulges himself to the max in that regard in Week End – the final scenes see resistance cells speaking on the radio using codenames like “The Searchers” and “Johnny Guitar” – even as he also constantly provoked his audience by also insisting on the reverse, interpolating long passages from books as read by his actors and nodding to other art forms constantly in his movies, as with Saint-Just’s speech. Almost exactly mid-movie Godard offers a vignette titled “A Tuesday in the 100 Years War,” his camera fixing that worm in the mud, whilst on the soundtrack the voices of the Durands are heard, considering their own ignorance and pathos in lack of self-knowledge, in an unexpected show of philosophical depth from the pair, even as Roland also offers self-justification in his way, arguing they must do as they do much like the worm, understanding neither the forces that move it or them.

Amidst many bizarre and hyperbolic scenes, one of the most extreme comes halfway through and presents in part the spectacle of Godard acknowledging the frustration he’s out to provoke with such moments, as the Durands, still seeking directions to Oinville, encounter Emily Bronte (Blandine Jeanson) and an oversized version of Tom Thumb (Yves Afonso) walking along a country lane, swapping quotations from books. Roland and Corinne become increasingly enraged (“Oinville! Oinville!”) as Bronte insists they solve riddles she reads to them from the book she’s holding before answering their questions, considering the answering of conundrums much more important than mere spatial location. The confrontation of 19th century literary method with modern cinematic virtues is enraging, and acknowledged by the two modern characters: “What a rotten film,” Roland barks, “All we meet are crazy people,” whilst Corinne rants, “This isn’t a novel, it’s a film – a film is life!” Finally Roland gets so angry he strikes a match and sets Bronte’s dress on fire. He and Corinne look on impassively as the flames consume the decorous poetess. “We have no right to burn anyone, not even a philosopher,” Corinne comments. “She’s an imaginary character,” Roland assures, to Corinne’s retort, “Then why is she crying?”

The dizzy turn from aggravating whimsy to apocalyptic horror in this vignette obliquely describes the simmering anger Godard was feeling against the Vietnam War which metaphorically pervades the film as a whole. Bronte’s burning conflating infamous images of victims of napalm bombing into a singular image of gruesome death, albeit one rendered in a fashion that refuses pyrotechnic representation of pain, as Godard doesn’t show the burning woman or have her screams fill the soundtrack, with only Corinne’s deadpan description to suggest that all an artist can do in such a moment is weep and not wail. Godard conceives as the war, and indeed perhaps all modernism, as direct offence to artistic humanism, whilst also accusing precisely that artistic humanism as continuing blithely through epochs of horror in the way Tom Thumb continues his recitation to the charred and flaming corpse. The theme of characters who know they’re characters engaged in frustrated hunts for obscure ends echoes the 1920s Theatre of Absurd movement, particularly Luigi Pirandello, although the surreal interpolation of such figures with affixed names of famous and mythic import in the context of such tragicomic sweep might be more directly influenced by Bob Dylan. At the bottom of things, moreover, Godard treats the political gestures and artistic interpolations alike as varieties of tropes in the modern sense, fragmented and nonsensical in the dream-logic of the narrative, part of the madcap stew of anxiety and despair the film as a whole proves to be.

And yet it’s the film’s islands of tranquillity that stand out most strongly when the texture of the work becomes familiar. The embrace of tractor driver and the rich girl. The sight of one of the revolutionaries, a “Miss Gide” (a cameo by Wiazemsky) reading and having a smoke as her fellows row in across a Renoir pond. The sight of Bronte and Tom Thumb wending their way along the country lane. A wounded female guerrilla (Valérie Lagrange) dying in her lover’s arms whilst singing a wistful song. Such moments lay bare the ironic peacefulness the idea of chaotic revolution had for Godard – the possibility that in the formless and perpetual new state of becoming he might find his own restless and relentless conscience and consciousness stilled and finally allow him to relax and take simple joy in the act of creating. The most elegant of these interludes, if also once more defiant in its extension, comes when the Durands are finally given a lift during their trek, it proves to be by a pianist (Paul Gégauff) who agrees to take them as close as he can to Oinville if they’ll help him give a concert he’s driving to. This proves to be a recital of a Mozart piece in the courtyard of a large, old, classically French farmhouse, given purely for the edification of the farm’s workers and residents. Coutard’s camera seems to drift lazily around in repeating circles, as the residents listen and stroll about lazily within their separate spaces of attention and enjoyment. The pianist stops playing now and then to comment on his own lack of talent and argue that contemporary pop music sustains much more connection with the spirit and method of Mozart than the disaster of modern “serious” concert music. Given the film around this moment, such a jab at artists going up their own backsides in the name of radical innovation and antipopulism in the name of the people be considered highly ironic jab.

The sequence is marvellous even in its salient superfluity except as a rhythmic break and interlude of pacific consideration, the pianist’s occasionally fractured recital mimicking Godard’s own cinema and the scene as a whole expostulating an ideal of art as something that reaches out and enfolds all, without necessarily dumbing itself down: if Week End’s ultimate project is to force chaos onto the cinema screen, it also exalts culture in the barnyard. Actors who appear elsewhere in the film, including Jeanson who acts as the pianist’s attentive page turner, and Wiazemsky, appear amongst the audience, whilst the Durands also listen, Roland yawning every time the camera glides by him and Corinne noting the player isn’t bad. In random patches throughout the scene bursts of sudden ambient noise, including the buzz of a plane engine, clash with the lilting beauty of the playing, as if Godard is pointing the difficulty of capturing such a scene on film considering the pressure of rivals in volume and attention so pervasive in modern life. Once the couple are dropped off further down the road by the pianist, the Durands resume their tramping. As they pass some men sitting on the roadside: “They’re the Italian extras in the coproduction,” Roland explains.

The appearance of Saint-Just earlier in the film is followed immediately by Leaud in another cameo, this time in a movie joke that plays on the cliché of people who want to make a phone call being stymied by some ardent lover speaking on the phone. Rather than simply speaking, the wooing lover insists on singing a song over the phone and cannot break from it until it’s finished, by which time the Durands have turned their acquisitive eyes on his parked convertible. Finally breaking off his song, the man battles the pair in another extended slapstick clash like the one in the car park at the start. The Durands find they’re not quite the most evolved predators in the countryside they like to think they are, as the skinny young man finally outfights them both, even jabbing his elbow into Roland’s spine to leave him momentarily unconscious, before fleeing. The movie joke is matched towards the end as Godard makes fun of another cliché, that of cunning warriors communicating with bird calls, as the Durands encounter a gangly man who will only communicate in bird noises, even holding up a picture of a bird before his face as he does so. This weirdo proves to be a member of a hippie revolutionary cell calling itself the Liberation Front of the Seine and Oise, who take the Durands captive when they in turn are trying to rob some food off some roadside picnickers they encounter.

Before the Durands are waylaid by the Liberation Front, they do actually finally reach Oinville, only to find their fears have been realised: Corinne’s father has died and her mother has claimed all of the inheritance. Corinne washes the filth off the journey off herself in the bath, with Godard positing another joke on himself, avoiding showing Corinne nude in the bath but including in the frame classical painting of a bare-breasted woman looking coquettishly at the viewer. Corinne’s fretting is meanwhile deflected by Roland as he angrily reads out a book passage contending with the way an animal’s invested nature, in this case a hippopotamus, defines existence for that creature. This scene is another multivalent joke that swipes at the different expectations of censorship levelled at cinema and painting as well as extending Godard’s motif of discursive gesture, which he reiterates more forcefully when the couple confront the mother. In between these scenes, a portion of the film the breaks down into random shots of Oinville with the title “Scene de la vie de province” with the sarcastic lack of any apparent life in the provinces, with Roland’s recital on the hippo on sound, vision punctuated by recurring titles from earlier in the film and random advertising art, threatening for a moment to foil all sense of forward movement in the story. Roland argues with the mother over splitting the inheritance for the sake of peace, whilst the mother carries some skinned rabbits she’s prepared. Suddenly Corinne sets upon her with a kitchen knife and the couple butcher the old lady, represented by Godard by torrents of more of his familiar, hallucinatory fake red blood (shades of Marnie, 1964) spilt upon the beady-eyed and skinless rabbits as they lay on paving pebbles. The couple take the mother’s body into the countryside and contrive to make it look like she died in yet another traffic accident.

Through all the discursive, masking, and symbolic devices thrown at the viewer with Week End, the overarching purpose accumulates. Godard contends with the constant provoking strangeness and slipperiness of representing life, experience, and concepts in cinema, with its duplicitous blend of falsity and veracity, its constructed simulacrum of reality, its overriding capacity to sweep over the viewer and make us feel perhaps more intensely than anything in actual life can, and Godard’s cold-sweat anxiety in not being sure if he as a film artist and suppliant lover is contributing to some deadly detachment pervasive in modern life particularly as it relates to awareness of the world at large. One can argue with the thesis as with many of the other attitudes present in the film – the average person in the modern world is constantly forced to safeguard their own psychic integrity in the face of a bombardment of stimuli and demands for empathy where in, say, the 1300s one’s concerns barely went beyond travails in the next village, and it’s this safeguarding that is often misunderstood at apathy or ignorance (whilst writing this I’m glancing at the TV news updates by thousands of deaths in the Turkish earthquake, of which thanks to the miracle of technology I’m instantly aware and constantly informed of, and can’t do a damned thing about). But what’s certain is that to a degree very few other filmmakers, if any, have matched, Godard creates a work that is a complete articulation of his concern, even if at times the film manifests its own blithely insensate streak, its determined attempt to burn through the veils of its own knowing and intellectual poise. Godard’s method is to constantly force a reaction through indirect means, proving that implication can sometimes pack the shock that direct portrayal cannot.

The long, self-consciously shambolic last portion of the film as Roland and Corinne are held captive by the Liberation Front, becomes a succession of blackout vignettes and vicious jokes. The “liberators” instead play Sadean anarchists and Dadaist provocateurs, raping, killing, and consuming captives – one part end of days hippie happening, one part inverted take on Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom with a bit of Lautreamont’s The Chants of Maldoror thrown in. Passages of the latter are recited in prototypical rapping over drum licks, as the Front have a drum kit set up in the forest glade that is their base for ritual expounding of evil art, companion piece and counterpoint to the piano recital. A captive girl is handed over to Ernest (Ernest Menzer), the Front’s executioner-cum-cook, who specialises in making cuisine with human flesh: “You can screw her before we eat her if you like.” Roland and Corinne are tied up, having been partly stripped and made filthy, likely in being raped and brutalised. Ernest roams around the camp, splitting eggs over prone bones and dropping the yolks on them, and then with the delicacy of a master chef does the same upon the splayed crotch of a female prisoner, before inserting a fish into her vagina – Godard managing to portray this grotesquery whilst still maintaining a judicious vantage, implying clearly without presenting any image that nears the pornographic – which, in its way, makes the scene even more squirm-inducing.

Some unknown time after being captured, the Front crouch with their captives near a roadside, waiting for passing travellers to waylay and add to the pot. Roland tries to make a break, and the Front’s chief (Jean-Pierre Kalfon), rather than let him be shot, instead hits him with a stone from a slingshot. Corinne stands over Roland, his head split open by the missile and bleeding to death: “Horrible!” Corinne moans. “The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome with more horror,” the leader replies, a line that might as well come out of Mao’s little red book, and can be taken as implicitly accusing nothing so petty as movie censors but the entire rhetorical infrastructure always mobilised whenever aggrieved and angry populations unleash that anger in destructive ways. Or, as apologia in dark tidings in glancing back at Stalinist purges and over to Maoist Cultural Revolution and on to Khmer Rouge killing fields. Or both and more. This cues the film’s most infamous moments as a pig is shown being swiftly and efficiently slaughtered, bashed on the head with a hammer to stun it before its throat is cut, and a goose having its head cut off, its body still flapping away pathetically when both animals are laid out for Ernest to add to his cuisine. Actual death on screen, inflicted on hapless animals, a profound provocation to animal lovers. Pauline Kael commented that for all Godard’s tilting at those who inflict horror and destruction, here was a bit of it he could own himself. And yet such scenes would be entirely familiar and commonplace to any farmers and slaughtermen in the audience but when placed in a movie become disturbing horror, given the average audience member’s distance from the realities that put food on the plate. Earlier in the film the farmer who ran into the young couple’s Triumph angrily declares people like her need people like him to feed them, and Godard only engages with that truism on its fundamental level.

The scenes with the Liberation Front, barbed as they are in portraying dark fantasy extreme of the radical dream, can also be taken as a sarcastic riff on Godard’s soon-to-be-ex-pal François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966), taking up the same notion of a fringe group in revolt against society with a project of sustaining works of art within themselves, but with a much less poetically reassuring upshot. Rather than memorising books to carry into an unknown future, these radicals read the books out and turn them into new, perverse forms of art, which warring on the society that has no time for such works. Some remnant flicker of narrative purpose returns for the film’s last five minutes, as the Front arrive at a rendezvous on a muddy road by a farm, the guerrillas all edgy and armed, to get the chief’s girlfriend returned, as she’s been taken prisoner by some obscure rival gang. Corinne is given over in exchange, as she begs to stay with the devil she knows. When a sniper sparks battle, the chief’s girl is killed, dying in his arms whilst warbling her last chanson. Here is Godard’s simultaneous indulgence and mockery of both movie images of romantic death for good-looking freedom fighters, as well as the way such images were held in fond imagination by a generational cadre of gap year radicals, in the way all good radicals should hope to die before age and disillusionment despoil us. Corinne flees, joining the chief in their flight back to the forest.

The last glimpse of Corinne sees her having shifted with ease that shouldn’t be that surprising from rapacious bourgeois to voracious cannibal, taking the place of the chief’s dead girl and listening to his sad musings on “man’s horror of his fellows.” The film’s punchline is finally reached like fate, as Ernest gives Corinne and the chief portions of cooked meat on the bone, a batch of human meat which the chief casually confirms includes parts of some English tourists from a Rolls Royce as well as the last of her husband Roland. “I’ll have a bit more later, Ernest,” Corinne instructs as she gnaws eagerly on her meal, before the fade to nihilistic black and “FIN DE CONTE – FIN DE CINEMA.” Of course, cinema didn’t end in 1967, any more than great Marxist liberation waves swept the Third World or France cracked up into chaotic guerrilla warfare and spouse-on-spouse anthropophagy. At least, not yet. Week End refuses to ease into a pathos-laden half-life of nostalgia the way most radical artworks tend to. As time-specific as the clothes and cars are, the daring of the filmmaking, the way Godard transmutes what he deals with into scenes at once abstract and charged with unruly life, still has a feeling of perpetual confrontation, of standing poised at the edge of a precipice. Not the end of cinema, but certainly one end of cinema, a summative point. Beyond here lies dragons.