.

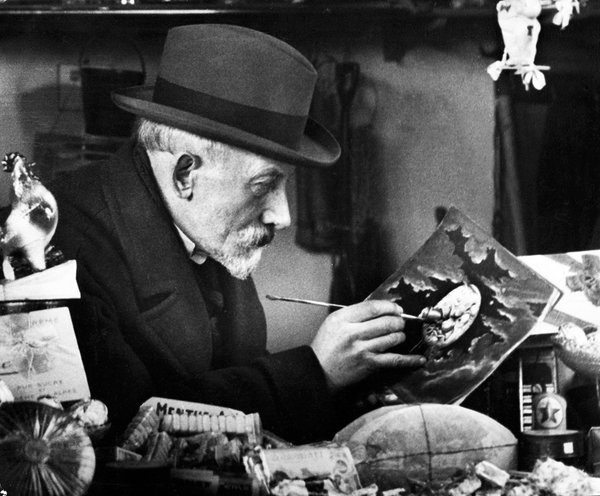

Director / Screenwriter / Actor: Abel Gance

By Roderick Heath

There is no other film like Abel Gance’s Napoleon. Though nearly a century has intervened since its release, scarcely any work of feature filmmaking has so completely revised and expanded what the form is capable of in terms of artistic invention and range of technique. With Napoleon cinema finally gained the complete expressive freedom open to other art forms, even if it was cursed to emerge at a moment when a new and dominant orthodoxy was taking a firm grip over what audiences would expect for the new thirty or more years – and, indeed, still persists for the most part. Gance’s innovations, including split-screen effects, handheld camerawork, associative montage and passages of non-linear technique, and the legendary eruption of widescreen, actually a kind of prototypical Cinerama, used in its climax, and doing so throughout with an entirely sovereign purpose in expressing a personal vision, make Napoleon an eternally modern and challenging as well as intoxicating in its cinematic impact. Few filmmakers have dared anything like what Gance attempted in even a vaguely similar context, in freely and furiously blending classical narrative and experimental film technique. And, like many of the major pioneering works from the age of cinema’s fitful adolescence, Napoleon has never been an uncontroversial film.

Gance had made himself the toast of French cinema with his international hit J’accuse in 1919, an earnest and blistering broadside against the recently ended First World War and the sullen attitude of the peacetime atmosphere, transmuted into a bizarre stew of message movie, melodrama, war film, domestic tragedy, and postmodern horror flick. Whilst not his first epic, J’accuse saw Gance embracing the better example of D.W. Griffith and applying to the screen every expressive and technical trick at his disposal, roving through aesthetic textures from harsh realism and high melodrama to the surreal and poetic. Sergei Eisenstein took inspiration from Gance’s electrifying editing. Gance stood resolute in his belief film as a maturing art form would become something much like opera, something an audience could devote a whole day to and become lost within its expressive universe. He pushed that belief to the utmost with his 1921 epic La Roue: Gance’s longest cut ran for nearly nine hours. He followed that colossus with the relatively small-scale but still ingeniously directed comedy-horror film Au Secours! (1924), starring the popular silent comic Max Linder, a film that nonetheless didn’t see release for many year. After dashing it off, Gance began gearing up for what he intended to be the project of his lifetime, a projected six-part biopic about Napoleon Bonaparte.

After laboriously piecing together financing for this project, not so much a white elephant as an actual, proper, trampling woolly mammoth of cinematic ambition, Gance produced his film in a whirlwind of enthusiasm and energy, and the result was nearly six hours long. The shortened version Gance screened at the film’s official premiere to a distinguished audience was met with great approval, but the film’s ultimate box office never quite justified the enormous expense, in part because it came out just as talkies were talking over, an innovation exhibitors would rather pay to accommodate than wider screens to fit Gance’s technical coup. So the planned follow-ups never eventuated. Gance instead ploughed all his energy into his talkie debut, the apocalyptic epic La Fin du monde (1931), another of his fugue-like sagas, but one that this time proved a huge disaster. Gance set about trying to play nice with the more conservative style setting in through the 1930s, if still producing major works like Un Grand Amour de Beethoven (1937) and a remake of J’accuse! (1938) that proved fateful in the countdown to another war’s outbreak. During World War II Gance earned some lasting enmity when he briefly supported Philippe Petain’s Vichy government as a potential saviour for the beaten and occupied nation, but eventually fled to Spain as the Nazi yoke became severe.

After the war Gance had a lot of trouble gaining backing for movies, but a revival of the much-edited and tattered Napoleon in the mid-1950s helped spark the imaginations of the young soon-to-be French New Wave film movement. Francois Truffaut worked to revive his critical reputation, Gance eventually made a sputtering comeback, with late films including Austerlitz (1960), a belated pseudo-extension of Napoleonic saga, and Cyrano and d’Artagnan (1963). But it’s chiefly thanks to the work of the English film historian (and sometime director) Kevin Brownlow that Napoleon is today in anything like the shape Gance originally intended. Brownlow, after purchasing some 9.5 mm prints of portions of the film he bought as an already movie-mad kid, was startled by the energy of the material he viewed, and began a grand quest to restore the movie. His first restored edition was unveiled for public screening in 1979. Francis Ford Coppola exhibited an edited version of Browlow’s restoration in 1981, equipped with a score by Coppola’s father Carmine, with the old and sick Gance able to listen in to the audience’s rapturous reception of that cut’s premiere by telephone. Brownlow released an expanded edition with newly rediscovered footage was screened in 2000. Like many others, I expect, Coppola’s version is the first I saw, but Brownlow’s second edit, with a score by Carl Davis, is the gold standard. Most importantly, this version does justice to Gance’s intensely concerted storytelling rhythms as well as the spectacle of his style and story, even if today, with our well-honed notions of how long a movie should be, it’s hard to absorb in a single viewing.

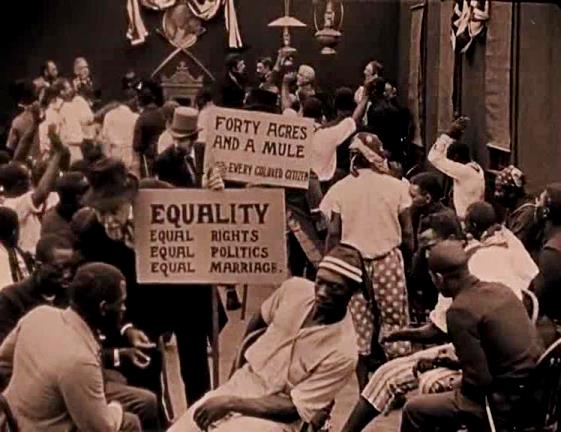

Just how one feels about the men at the eye of this maelstrom inevitably colours response to Napoleon. The General turned Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte undoubtedly did much to put the ailing French Republic on its feet, granting it political stability, a radically modern governing code, and vast wealth. His swathe of conquest brought liberation and liberalisation to populaces still living under medieval regimes and worldviews, whereas the radical gravity of the French Revolution only devolved into spasmodic factional slaughter. Bonaparte’s campaigns also caused the deaths of millions, involved the plunder of wealth from around Europe, saw the crucial betrayal of core tenets of the revolutionary cause he affected to spread, and brought eventual disaster to so many who placed faith in him, even if that faith continued to burn through the stolid, repressive epoch that followed. These are the essential contradictions historians, artists, politicians, and philosophers have argued about for the last two centuries and will do so for at least two more. Ludwig van Beethoven famously offered Napoleon initial admiration and eventual, furious repudiation. Friedrich Nietzsche succinctly described him as a chimeric blend of his ideas of the übermensch, the super-man, and its opposite, the üntermensch, the monster.

The most sublime and perturbing aspect of Napoleon then is the degree to which it is a study in its own vehement, rapturous creative energy, a portrait of a grand visionary accomplished by a man determined to prove himself a grand visionary. Gance worked in merry ignorance of Berthold Brecht’s dismissal and revision of the idea of the epic, instead attaching the engine of his imagination and talent to a suitably enormous subject. Gance’s concept-cum-assimilation of Napoleon is also a successor to J’accuse’s main character, the wounded warrior-poet Jean Diaz, swapping the tattered, morally exhausted, if still yearning, beauty-seeking spirit expressed through that character for Gance’s idealised Napoleon, the emblem and sharp leading edge of a great, potentially transformational moment in history. More concretely, there seems to be a jarring gap between J’accuse’s antimilitarist statement, and Gance’s lifelong expressions of pacifist and apolitical feeling, with his celebration of a man who was the quintessence of military leadership, one who, at the film’s climax, begins the great rampage of his career. Much of this can be simply explained as a refuge in historical dreaming, a ready attachment of positive feeling onto something safely gone and swathed in legend, but some have felt Gance’s idea and images strayed too close to a quasi-fascist celebration and apologia for dictatorship at a time when those forces were gathering strength across Europe.

One key to all this is the degree to which Gance essentially refashions the erstwhile Emperor in his own image, as a pure incarnation of poetic faith in an idea of France in particular and human possibility in general, but also more specifically as an artist working in his own special medium. So, Gance’s Napoleon becomes a man often glimpsed wandering and meditating, steadily gathering his powers for dramatic gestures. His gaze cuts through illusions of strength and distracting clamour to get constantly at the essence of matters, and applying a world-sweeping vision with decisive strokes. But his vision is often misunderstood or ignored by lesser people lacking such conceptual zest. The film’s famous opening scene depicts the boy Napoleon (Vladimir Roudenko) residing as a student of Brienne College, a religiously-run military school for the sons of prominent families. Napoleon trails his Corsican roots prominently with his surname styled as Buonaparte and given name he pronounces as “Nap-eye-ony,” mocked by the instructor Pichegru (René Jeanne) as “Paille-au-nez” or straw-in-the-nose. The school has a regular winter ritual, a huge snowball fight blended with a game of capture-the-flag, where the students are encouraged to bring their nascent combat wit and tactical guile to bear.

Napoleon, leading a small and assailed band against a force that includes the bullies Phélippeaux (Petit Vidal) and Peccaduc (Roblin), two future battlefield opponents, proves his emerging, unflappable grit even as he foes pelt him with snowballs with rocks hidden within. Warned of this dirty trick by the cry of the school’s sympathetic everyman cook Tristan Fleuri (Nicolas Koline), the enraged Napoleon leads a successful charge and captures his opponents’ flag, bringing it back to his redoubt in the snow. Despite his mockery of his name, Pichegru pronounces the proud and fiery lad will go far. For revenge, Phélippeaux and Peccaduc release the pet eagle Napoleon keeps, sent to him by a relative back in Corsica. Napoleon is so upset by this he starts fighting the entire dormitory of fellow students in a frantic melee. He’s locked away in a classroom by the staff to quell his furore, and the eagle flies back in through the window, becoming his symbolic familiar for the rest of the film. Gance immediately defines Napoleon through his practically preternatural gifts for leadership and combat coupled with a disconcerting otherness that tends to irritate and provoke rivals and authority, character traits that will earn either ruthless condemnation oblivion or a chance to revel in greatness: the historical moment will provide plenty of chances for the former but also a singular opening for the latter.

During the snowball fight sequence, Gance wields the intensifying cinematic technique that flows throughout the film, including split-screen effects displaying multiple actions simultaneously, shots taken with a handheld camera for lunging, immersive physical immediacy, and double-exposures that place the young Napoleon’s face and reactions to the battle at the centre of a dizzying, more than faintly ironic sprawl of images that evoke his later successes: within the first fifteen minutes of the film, Gance has already executed one of his signature sequences building from deadpan to ecstatic flux of style and story. The boyish purity of this victory is immediately contrasted with the overtones of ethnic condescension for the Corsican boy and the disdain for his pride and ability. Tristan’s fondness for young Napoleon is signalled when he warns him during the snowball fight and later brings him his cap and coat during his exile to a cold attic of the military school, as Napoleon lounges despondently on a cannon. This moment, an almost paternal gesture from the cook to the gutsy lad, is also touched with symbolic inference: Napoleon’s future metier and speciality as an artilleryman is described, the essential common man Tristan vesting him with his warrior garb as the select hero for the people. One of the lines of tension within Napoleon as a film then is the way the film views its hero as, simultaneously, an outsider and patriotic paradigm, artist and authority. Rather than trying to reconcile these tensions or set them in argument, Gance accepts them as part of the florid, dizzying, contradictory energy of the epoch he portrays, one where the line between heroism and monstrosity are easy to trammel.

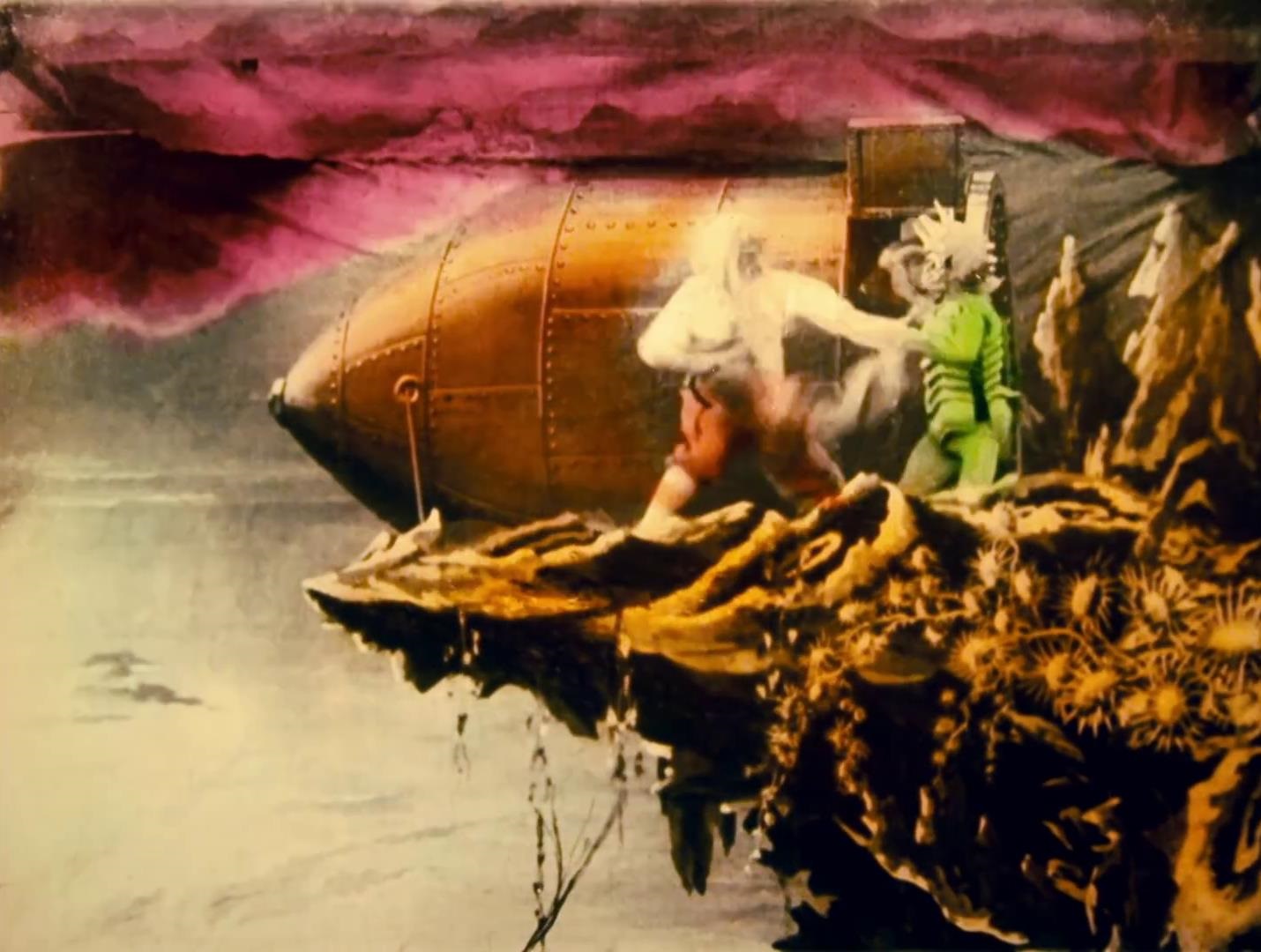

This wild, protean quality is manifest not just in Napoleon but also in the mighty figures of the Revolution, including Georges-Jacques Danton (Alexandre Koubitzky), Maximilien Robespierre (Edmond Van Daële), and Jean-Paul Marat (Antonin Artaud), who are collectively described with a parched level of irony as “The Three Gods” in the revolutionary climes, as well as attendant figures like Louis de Saint-Just (Gance himself).The opening depiction of the boy Napoleon segues immediately into the headiest moments of world-changing excitement during the Revolution, with the Three Gods ensconced in a private chamber adjoining the great hall of the Club de Cordeliers, a centre of the revolution’s ferment, where the ardent free-thinkers and rebels gather, whilst the real power is gathered in the hands of the three machinating minds within. A young officer, Claude de Lisle (Harry Krimer), arrives on a peculiar mission, assigned to perform the new song he’s written as a patriotic anthem, “La Marseillaise,” and Camille Desmoulins (Robert Vidalin), calls Danton out to hear it. The song goes over a treat, to the point where Napoleon (Albert Dieudonné), now grown and a Lieutenant of artillery in the army who’s been perched in boding solitude amidst the audience, approaches De Lisle and thanks him: “Your hymn will save many a cannon.” In this scene Gance introduces one of his flightiest flights of fancy, one that recurs throughout the film, as he slowly dissolves from the sight of Danton belting the song out lustily to a vision of the song itself personified as a figure akin to Delacroix’s conception of liberty, a sword-waving, flame-wreathed shield-maiden (Damia).

As with much of the film that follows, Gance alternates such imagery of high patriotic pomp and poetic licence with a mischievous sense of humour and oddball detail that evokes the texture of Charles Dickens and Gance’s favourite writer Victor Hugo, and artwork of the period, if closer to the grotesque and madcap human sprawls of Hogarth than the noble classicism of Jacques-Louis David, although he later recreates David’s painting of the dead Marat in his bath. Gance’s conceits range from the shirtless strongman standing guard to the Three Gods’ chamber with “Mort au Tirans” scrawled on his chest, the earthier, plebeian counterpart as the fist of liberty to the mystical shield-maiden, to a slovenly sans-culotte asleep with face nuzzled against a classical sculpture, and with vignettes of historical curiosity that evince the strange new possibilities of the revolution, like Desmoulins working alongside his wife Lucile (Francine Mussey), and a woman in the crowd wiping her thrilled tears on the tricoleur. The Three Gods meanwhile are identified one by one in sharply composed portraits, Danton all wild-haired, brusquely muscular energy, Marat with eyes alight in obsessive fervour, and Robespierre with round, dark glasses on, a black-eyed raptor with smooth white face awaiting the purification of the faith.

Gance notes Robespierre and Marat conversing with evidently foreboding meaning whilst Danton is outside leading the song, Marat musing on the decapitated head of a statue of Jesus lying on the floor, whilst Robespierre lounges on a chair which has been carved into the film’s recurring eagle symbol, a false and wooden edition, the light of communal excitement falling in slanting rays behind him that slowly fade out. Meanwhile without Gance cuts between close-ups of the singers with increasing speed and a sense of virtually orgasmic climax. It’s likely impossible to know if Michael Curtiz ever saw this scene, but it certainly anticipates the famous “La Marseillaise” scene in Casablanca (1942). Gance views Napoleon as one of the crowd and yet also peculiar and singular with his slouching posture, turned initially from the performance but revealed to have been paying keen attention. It’s signalled here that Napoleon, as well as appreciating the song for itself, is also a key to something important and power, the patriotic idealism that can be harnessed but which be wasted in the course of the Revolution’s darkest turns. Napoleon weathers one of those when, in his cheap and grotty little room, he tries to write whilst the deposing of the monarchy is celebrated by a jubilant crowd, who entertain themselves by hanging a few luckless royalists from lampposts and even from the bars on Napoleon’s balcony.

“Fragments of a great event, seen from a tiny room,” reads a title card, as the tumult of banners and raised, severed heads on pikes against the light out in the street casts a strange, eerily flickering glow on Napoleon’s face, before the surreal mixture of gaiety and violence come close. Napoleon considers grabbing a pistol as the revolutionaries tie a hanging rope to the balcony, tempted to intervene with fruitless heroism or perhaps kill himself in the face of such cruelty, but snatches his hand back before doing either. Following Napoleon’s sad and knowing gaze, Gance cuts with an ironic power Eisenstein would surely have appreciated from a shot of a revolutionary’s hand, covered in blood, to the copy of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen he has pinned to his wall, and then shifting into a slight camera pan off the Declaration to view the howling mob and bloody hangmen without. Glimpses are also offered of King Louis (Louis Sance) and Queen Marie (Suzanne Bianchetti) on trial, and Danton whipping up an audience by a blacksmith’s workshop, tearing a horseshoe in half: “This is what you have done to the monarchy!” Gance punctuates the scene with another startling spasm of near-subliminal cuts between the images of the wild night and Danton’s exultant audience, punctuated by the pounding of the blacksmith’s hammer driving sparks and fire.

The monarchy’s downfall is the cue for kindling Napoleon’s sense of mission, “a light growing within him” that turns him into the vessel for Gance’s poetic meditation on the wild, awful scene. Napoleon has already encountered one important element of his future. Walking to his pension with holes in his shoes stuffed with paper, he is recompensed by a mesmerising glimpse of Joséphine de Beauharnais (Gina Manès), in the company of her gentleman friend Paul Barras (Max Maxudian), described by a title card as “the idle rich,” as they call on the fortune teller Mademoiselle Lenormand (Carrie Carvalho), the fortune teller. Likewise Josephine’s eye is briefly caught by the bedraggled but piercing-eyed young lieutenant. Soon the fortune teller informs Josephine she will become a queen. Meanwhile Napoleon’s journey is counterpointed, and sometimes influenced, by odd acquaintances. Tristan is his Everyman familiar, the French average Joe, often changing jobs with the shifting tides of national fortune, becomes first a tavern owner in Toulon and then a clerk charged with processing death warrants during the Reign of Terror. If Tristan is spiritual father and emblematic common man attached to Napoleon, his daughter Violine (Annabella), who first catches sight of Napoleon when he comes to their inn at Toulon, thereafter dogs Napoleon’s trail with an ever-growing and obsessive ardour, becoming his priestess, his idolater, his wretched admirer and spiritually communing lover.

Napoleon’s life in Paris as an anonymous and poverty-stricken young officer is described chiefly in a comic vignette, as Napoleon is infuriated when a street cleaning cart rolls by, the spurting water soaking his legs and dissolving the paper stuffed in his holed shoes, earning a glare of pathetic wrath from the future emperor. This throwaway moment shows that Gance’s encounter with Linder and the silent slapstick tradition with its fine feel for everyday frustration and the human comedy wasn’t entirely lost. In a scene still missing from the reconstructed film, Gance also introduced Napoleon’s fellow Corsicans, Saliceti (Philippe Hériat) and Pozzo di Borgo (Acho Chakatouny), who lived in the same boarding house as him in Paris but didn’t like him, and the two become perpetual antagonists. When Napoleon is sent to Corsica as an official emissary of the National Convention, where he soon finds himself and his family in danger when he learns that the island’s president, Pasquale Paoli (Maurice Schutz), with Di Borgo in league, is plotting to let the English invade and occupy Corsica, and Napoleon is marked for arrest or assassination because of his direct connection to the Convention. Saliceti whips up a crowd in condemnation of Napoleon, who’s been warned of the plotting by aged shepherd Santo-Ricci (Henri Baudin). Napoleon’s brothers Joseph (Georges Lampin) and Lucien Sylvio Cavicchia) sail to Calvi to fetch French intervention, whilst Napoleon elects to confront his foes and make an escape whilst the rest of the family, including mother Letizia (Eugénie Buffet) and sisters Élisa (Yvette Dieudonné) and Pauline (Simone Genevois) flee to the forest.

“From this moment until his return to France, the life of this young officer becomes the most incredible of adventure stories,” Gance’s title card promises. The Corsican vignette, whilst a tiny, barely-known episode in terms of Napoleon’s whole life, in many ways becomes the scene of Gance’s most lucidly composed and executed vision, again structured as a slowly but remorselessly building cinematic crescendo. It’s also Gance’s most idealised in dealing with his hero as a figure of almost mystical power and vision to a point bordering on the absurd, viewing it as the first true challenge to his survival talent and personal courage, one that provokes his innermost potential to finally hatch out. Early shots in the chapter depict Napoleon as a solitary figure communing with the Corsican landscape and the sweep of the ocean, a warrior-poet in touch with the elements and awaiting his moment away from the pettiness of the world already gathering forces to destroy him. In the course of his flight he becomes a figure to no small degree like Jesus in Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1926), inspiring awe and flinching caution from people who nominally want to kill or imprison him, as he boldly appears in a tavern filled with men from rival political factions, each demanding a different foreign political alliance and whose one point of agreement is “Death to Napoleon Bonaparte!”, until Napoleon reveals himself and declares, with mystic light in his eyes, that only France can be their future.

Napoleon extends his daring spectacle of defiance by riding into Ajaccio, stealing the tricoleur hanging on Paoli’s house, and raising it as a sail on a skiff he commandeers to try and sail to France, bellowing defiantly at his pursuers left back on the shore, “I shall bring it back to you!” Like so much of Napoleon, this bisects the zone between inspired artistry and gilding the lily, redeemed by cunning, thrilling flourishes like Napoleon spotting a rope strung up to topple him from his horse and casually hacking it through with his sabre with the poise of a great movie swashbuckler. Back in Paris, Robespierre, in counterpoint to Di Borgo’s rabble-rousing, denounces the Girondin faction along with Danton. Taking as his cue descriptions from the heady days of the National Convention that it was like riding out a storm at sea, Gance intercuts between Napoleon weathering a furious gale on the ocean with the tumult unleashed by the denunciation in the Convention, the lash of waves on the boat intercut with a camera mounted on a swing to evoke the sensation of furious, rolling energy. Other, less spectacular shots still wield astonishing art, like a silhouetted Napoleon on his horse, riding for freedom along the Corsican coast, a threatened but still glowing sun piercing through stormy clouds above. The first of the film’s three parts ends as Napoleon is picked up by a ship bringing his brothers back, they fetch the rest of the family from the shore, and head for France, which Napoleon now declares will be their only home.

Gance’s overarching aesthetic desire, to communicate the thrill of his concept of the history he portrays as if he can manifest a sense of physical force through raw filmmaking, also depends on Dieudonné’s capacity to work against his project, insofar as Napoleon is so often envisioned as the stoic pillar at the centre of it all. And yet despite Gance’s idealisation, the character emerges as anything but a waxwork impersonation. In his late thirties when he making the film, Dieudonné was older than the man he was portraying, apparently a sticking point for his friend Gance when he was casting the film, but he reportedly convinced the director to cast him by donning a long black wig. Dieudonné proves readily able to shift between the various stances in the role Gance demands of him – zealous patriotic oracle, terse and tough warrior, musing witness of ugly history, playful would-be father, and a fiery but uncertain lover in a manner reminiscent of Shakespeare’s conception of Henry V – he hires an actor to coach him when he sets out to woo Josephine in the film’s last part. So strong is Dieudonné in inhabiting the character’s body language that when a title card reports him demanding of Tristan, “Bread, olives, and silence!”, you can virtually hear how Dieudonné delivered the line. Dieudonné apparently, eventually took the role and its singular status in his long career so much to hear he had himself buried in his costume, when he died at the age of 87.

His performance is particularly impressive in its vivacity and cohesion given that Gance hesitates to psychologise the future Emperor. Gance views him rather as one of those people who simply is what they are, born with a certain character and capacity, and whilst buffeted by events eventually proves able to master them. His Napoleon is in fact blissfully free of the traits of the modern world whose ugliest birth pangs Gance had already dealt with, a last gasp of the reflexive human before the age of the analytical human. It’s worth comparing the film’s portrait of Napoleon to the one in Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo (1970), where Rod Steiger captured aspects of mercurial genius and applied energy balanced by monstrous ego and almost childish entitlement, and riddled with flashes of pathos as he knows his time is running out. Gance, by contrast, prints the legend, but in his own, personalised way. He zeroes in on moments that certainly temper something in the man, from weathering school bullying and ethnic resentment, to holding back from grabbing up his gun to shoot the lynchers, in vignettes that demand and receive his circumspect restraint. These imbue him with a good sense of when exactly he should act, as he declares immediately before going on the offensive in Corsica. Gance communicates the speed of Napoleon’s mind with touches like an illustration of the map of Toulon with equations and manoeuvres speeding across it, cut in with the furious churn of montage.

The traits that make Napoleon interesting and singular are nonetheless those that constantly provoke different, mostly lesser personalities and minds, like his first commander at Toulon, General Carteaux (Léon Courtois), and his rivals Di Borgo and Saliceti, contrasting worldly leisure and pleasure with his brand of discipline and focus, as well as a genius for perceiving military matters incomprehensible to them. Carteaux dismisses his clear and essential insight when it comes to driving the British out of Toulon, whilst the commander of the French Army in Army, currently stuck hovering in the Alps General Schérer (Alexandre Mathillon), sends back his suggested plan for invasion with a note stating they were drafted by a madman who should try implementing them himself. Gance’s obvious pride at working in many a line and note taken directly from historical sources sees every authentic quote marked as “historical,” even the slightly dubious moment when a young Horatio Nelson (Olaf Fjord) sailing as a Lieutenant on a British warship, spies and wants to sink the ship carrying the Bonapartes away from Corsica, only to be told by his captain not to bother.

The battle for Toulon takes up the first half of the middle third but also cap the “First Epoch” as Gance’s title cards have it. The general replacing the incompetent Carteaux, Dugommier (Alexandre Bernard), makes Napoleon commander of the artillery and gives him the go-ahead to implement his plan to drive out the British, who control the city and the bottled-up French fleet, which involves capturing a specific bastion. Napoleon, putting together a force of soldiers he dubs the “Battery of Men Without Fear.” Launching his attack and night during a pummelling rain shower that soon becomes a hail storm, Napoleon battles both the English and opponents in the French ranks including Saliceti, who berate him for taking such an enormous risk, but Napoleon’s brusque confidence reinforces Dugommier’s trust, and the commander lets him continue. In a brutal, hand-to-fight fight, the French capture the bastion. In retaliation, Admiral Hood (W. Percy Day), commander of the British naval squadron, orders the French fleet burned.

The battle for Toulon is another amazing bit of filmmaking as Gance successfully recreates the chaos of such a struggle, an onrush of manpower and frantic, almost crazed violence, men grappling in the muck and duelling with sabres. Mixed in are flourishes again touching the surreal, as men are swallowed by torrents of mud, their hands reaching out of the squirming muck like zombies in a horror film, and a bizarre tattoo beat out on the regimental drums by the falling hail. Again, Gance weaves in relieving vignettes of humour and piquant detail, including Tristan cheering Napoleon on from the window of his tavern just as he did back at the military college. His young son Marcellin (Serge Freddy-Karl), now the Battery’s young drummer boy, sneaks into the fray hidden under his drum, which seems to undulate self-willed across the muddy battlefield, so he can strike at Redcoats, only to be swept up and spirited away by Violine. Gance presages the concluding shift into widescreen triptych images as the more traditional ratio splits into three to evoke the tricoleur whilst offering vantages on Napoleon standing resolute amidst the carnage. Despite the exaltation of Napoleon’s military prowess, Gance returns to the ambivalent mode of J’accuse when, the battle finished, his camera pans across the field littered with dead and wounded men, with Napoleon standing a vigil in the rain in appreciating the cost of victory. Finally, after falling asleep on the battlefield, his men plant standards around his sleeping form, whilst the eagle perches atop a post, now fully fledged as the emblem of martial glory.

Napoleon of course deals with historical events that are the stuff drilled into the heads of French schoolchildren, but otherwise the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras are phenomenon is largely known through the viewpoints of other nations, particularly Great Britain with its resolute resistance and counter-mythology as expressed through the likes of A Tale of Two Cities and the imagery of Wellington and Nelson, or for the Russian slant, War and Peace. In this regard Gance’s decision to focus on the early part of Napoleon’s career allows him to highlight less-known moments, and to encompass what he sees as the necessary backdrop for the man’s rise in the slide from exultant energy to petty tyranny that was the Revolution’s course. Whilst not particularly interested in the issues of the moment and emphasising the pointlessness of internecine strife, Gance’s demarcations of the leading personas like Danton and Marat lead of course to their deaths come on with a zest blending a newspaper caricaturist’s electric sense character essence and flashes of poetic extrapolation. Danton’s fate under the guillotine is prefigured when Gance superimposes a shot of a plunging guillotine during the downfall of the Girondins.

Artaud’s Marat, with eyes that almost seem to burn a hole in the movie screen (just as he did in a different if no less fanatical role in the following year’s The Passion of Joan of Arc), gets his comeuppance from Charlotte Corday (Gance’s then-wife Marguerite) in the bath. The denunciation of Robespierre, Saint-Just, and the other bigwigs of the hated Jacobin faction sees Gance give himself a flashy moment that also dares make room for sympathy for the devil, his face offered in close-up as Saint-Just defends their labours with his own visionary tilt of the head and flash of the eyes – “Have you forgotten that we have forged for you a new France, fit to be lived in?…We have achieved all this with that vulture La Vendee at our flanks, and on our back that pack of tigers – the Kings!” That Napoleon’s own life was briefly in danger from the Terror is something that’s been debated by historians, but Gance readily offers it as another unit of drama in the tale. When Napoleon refuses to do the regime’s dirty work by fighting the bloody insurrection in the Vendee region, which he considers a disgraceful case of French killing each-other, Salaceti is able to easily convince Robespierre to condemn him.

Tristan, taking a job as a clerk in an office charged with the Reign of Terror’s bureaucratic niceties, finds himself charged with processing the death sentences of both Napoleon and Josephine, the latter tossed into prison by Saint-Just. In one of Gance’s inspired Dickensian touches, the office also includes an aged clerk mounted on a hoist constantly ascending and descending a towering filing cabinet upon which court verdicts, mostly sentences to be decapitated, pile up, described as “the Thermometer of the Guillotine.” Tristan gets clerks Bonnet (Boris Fastovich-Kovanko) and La Bussière (Jean d’Yd), two real historical personages renowned for disposing of some death sentences by literally eating them surreptitiously, to consume Napoleon’s warrant. Josephine meanwhile is saved from the tumbril first by her ex-husband, Alexandre de Beauharnais (Georges Cahuzac), who elects to be the one person of that name called to the guillotine – “For once, madame, let me take precedence,” he suggests to Josephine. Later, in a fit of sobbing despair, Josephine encounters Lazare Hoche (Pierre Batcheff), a young and romantic aristocratic general also imprisoned and expecting to die, and they help each-other weather the storm until the Jacobin downfall. Soldiers barge into the “Thermometer” office, the old clerk bobbing on his hoist with amusing pathos, and soon all the prisoners are released.

In the eruption of gaiety that follows the end of the Reign of Terror, where the survivors of the Terror or the dead’s relatives gather to celebrate survival and indulge the orgiastic pleasures of living with some accomplished debauchery in an event they call the Victims’ Ball, Napoleon once more encounters Josephine as one of three beauties chosen to be exalted at the party. Deeply smitten, he sets out to woo her, with Hoche removing himself from the equation when he realises the fierceness of their attraction. Dejected and without a role following his plan to invade Italy is rejected, Napoleon nonetheless finds himself positioned to play the hero again when he’s fetched by the National Convention to defend them when a mob of resurgent royalists gathers to attack them: Napoleon, arming all the members of the Convention and having his first, fateful encounter with Joachim Murat (Genica Missirio), displays his casual expertise in dispersing the horde. Josephine in turn brings to bear her influence on Barras, now one of the main inheritors of power in France, to get Napoleon appointed commander of the army in Italy. Napoleon, upon hearing this news, takes down the rejected plan he had used to cover a hole in his garret window, determined now to implement it, and elects to quickly marry Josephine. Napoleon has already, incidentally charmed Josephine’s son Eugène (Georges Hénin) by letting him keep his executed father’s sword, and he resolves to play father to him and sister Hortense (Jeanne Pen). Meanwhile Josephine takes in Violine, after finding her collapsed and unconscious outside the house after spending so long lurking around in a lovestruck daze for Napoleon: after being restored to health, Violine helps get her father a job in the household.

Napoleon is of course a portrayal of a historical epoch and also a product of one. Gance’s delirious visions of the debaucheries of the Victims’ Ball, including female guests swanning around in increasingly provocative gowns and ending the night with bared breasts, is as much a portrait of the excess of the Jazz Age following hard upon the Great War as it is a depiction of the liberated mood of after weathering the Reign of Terror, and also an interlude of naughty hype. Gance delivers a good joke Harold Lloyd or Buster Keaton would’ve been proud of, in presenting, after a menacing title card reading “The Reaction,” the sight of a man dressed as a jailer passing through a throng of people dressed in prison clothes and barred gates, and beginning to read from a list as if announcing the condemned, only for this to prove to be the start of the Victims’ Ball, the list a menu of the delicacies on hand. Gance even indulges a little gender-bending as Tristan starts flirting with a laughing woman only to realise it’s a man in drag. Something of the imminent grimness of the Depression is also presaged too as Napoleon notes he poor around his neighbourhood, desperately cold and cueing for charity, and seeing it in terms of a larger project: “If the Revolution hasn’t found its leader by the end of the week, it’s finished.”

Napoleon also intervenes to save Saliceti and Di Borgo from being hung by a republican mob, after they try to assassinate Napoleon as he fends off the Royalists: he’s saved by accident thanks to Tristan, serving as a volunteer, discharging his gun and distracting Saliceti’s own aim. Napoleon, whilst noting that he cannot forget the compatriot duo’s wrongdoings, he does forgive them. It’s odd that Gance singled Saliceti out to be the central antagonist to Napoleon in his account, given that the real Saliceti helped Napoleon’s career and, whilst opposed to his eventual coup to become dictator, served under his brother Joseph’s regime in Italy. I feel like Gance wanted an opponent who was close to a doppelganger for the character, springing from the same background, same soil, but doomed to play in constant, stumbling lockstep with his omnicompetent foe. Meanwhile the man himself remains locked within his own genius, one that imbues tunnel-visioned focus. That focus is capable of landing anything he sets his mind to from an enemy redoubt to Josephine’s heart to trying to cure national and international ills, but too oblivious to rival wills and projects.

Perhaps the greatest hesitation Napoleon inspires as a film is that it’s too much – too much dazzling technique, too much genius, too much enthusiasm, too much movie in all. It’s a film that feels like the product of a choice on Gance’s part, after indulging his deepest tragic sensibility in J’accuse, to refuse tragedy and instead embrace a winner, to chase an image of achievement that transcends the barriers of mere strife and warmongering, and rather borders on crusade – a choice, perhaps, too many were willing to make around the same time. Gance nonetheless mediates on his choice in odd ways. He gives sympathy to the devil, as with Saint-Just’s self-defence, and contends with the way the idea of Napoleon as much or more than his actuality becomes a cult for the French. He wields Violine as the emblem of a France enraptured by the emerging Napoleon, buying a figurine of him from a street vendor when he’s hailed as a saviour after helping the Convention, and later installing a shrine to him including such memorabilia and keepsakes, turning him into a living god, in a way that intuits something important about the way the Revolution’s secular and atheistic tendencies nonetheless gave birth to a kind of demigod ideal that needed Napoleon to embody it.

In the film’s last quarter Gance takes this fascination with personal interpretations of faith, ardour, and destiny to some odd but revealing places, analysing his own compulsive project even whilst indulging its highest flights of fancy. Napoleon himself, when being taught by his actor friend how to make overtures to Josephine, imagines her face projected onto a globe and nuzzles against it as if to make love to beloved. This flourish of delightful, rather fetishistic illusory passion also includes Gance’s cumulating irony, as he notes the promise and threat of Napoleon’s desire to conquer his lady as conflating already with a desire to conquer the world at large. Violine, practising her secret faith, mirrors Napoleon’s indulgence of illusion, as she goes through her own mock wedding ceremony in the privacy of the room Josephine has given her, having adopted Josephine’s curled hairstyle in an effort to remake herself in the image of her idol’s lucky lady. Violine positions the Napoleon figurine she bought with shadow projected on the wall so can have the illusion of embracing her beloved for the nuptials-sealing kiss. Late in the film, Josephine comes into Violine’s room and finds her praying at her shrine, but rather than getting angry, understands the impulse well and succumbs to the same urge, kneeling by her friend-sister-rival-comrade to join in her vigil.

The dreamy texture of these scenes are arresting as a stylistic antistrophe from the history-written-with-lightning verve of the rest of the film. In a lot of ways the vigil of Josephine and Violine is its proper ending and punchline, certainly its interest in the zeitgeist of France in the time and metaphorical engagement with the Napoleonic idyll, having cycled through a portrait of the various, failed saviours of the nation giving way to the last, best hope, a virtual religion sparked. Here Gance’s depiction of obsessive ardour is twinned in a swooningly evoked but actually irony-flecked manner, watching as these people begin to get lost in the mists of their personal dream-visions and obsessive objects, even whilst affecting to deal with reality, their fantasias of longing bound to collide with less comforting results. This is taken a step further in a vital scene, which sees Napoleon, before heading off to take command of the Italian campaign, stops to visit the National Convention, deserted in the middle of the night. Taking to the rostrum, Napoleon now conjures up an audience and the shades, real or imagined, of the various, dead Revolutionary leaders, particularly the Three Gods but also many others. The shades feed him a succession of oaths, including to take over as the Revolution’s leader and to take it into Europe to forge the Universal Republic, all of which Napoleon swears to. The spectres are satisfied, but Danton’s warns him that if he ever betrays the Revolution they will turn against him.

This vignette is exceedingly important, in terms of the film’s overall meaning, and in indicating where Gance might have headed if he had made further instalments in his epic cycle. Perhaps he intended a rise-and-fall arc that would have seen Napoleon increasingly drifting within a bubble bound to pop and realise his mistakes too late. Gance uses this sequence regardless to place an important precondition on the very end’s depiction of Napoleon marching into Italy: so long as it’s being done in the name of a vital, humanistic cause, and with an ultimate eye towards dispensing with warfare as a necessary end, rather than making it a self-sustaining paradigm and Moloch-like dark god demanding victims, Napoleon’s purpose is righteous. The sight of the ghostly Convention singing “La Marseillaise” before fading from Napoleon’s vision meanwhile revisits the army of the dead at the end of J’accuse, and containing not merely patriotic triumphalism but fear too, an anxiety of a cause terribly wrung and battered by events, but subsisting still. Gance might well ultimately have been glad he never had to make the other films, that said. How could he have sustained the same creative pitch, and how deeply might he have wrestled with the hero-worship he indulges here when forced to? It seems as if the subplots involving Saliceti and Di Borgo, Violine and Tristan, were meant to extend into future movies, but all of them find a satisfying conclusion within this narrative, playing out their contrapuntal roles whilst finally all feeding into the core legend.

In any event, Gance shifts from the sight of Josephine and Violine praying to their man-god together to the man himself riding in a coach to join his new army, handing out messages to riders alongside in a first display of whirlwind command and decisiveness when freed to it, before finally abandoning the coach itself for horseback to speed more quickly to his goal. Finally he reaches the army, encamped in the Alpine foothills at Albenga, where he’s confronted by a rag-wearing, slovenly, entirely demoralised force led by a collective of grumpy and resentful officers who have resolved to cold-shoulder the popinjay being foisted on them. But Napoleon looks over officers and men alike with his formidable gaze – cueing another memorable historical quote from one onlooker, “With his piercing looks, this little stump of a man frightens me.” Napoleon breathes fire into the ragged force that will “awaken with the spirit of the Grand Army” and announces he’s going to lead them down to “the most fertile plains in the world.” Here Gance executes his ultimate moment of cinematic largesse, as the film erupts into what was called Polyvision by its developers – a widescreen vista captured by three cameras mounted together. This technique allows Gance to swap between panoramic shots, beholding the mass of men and the expensive scale of his staging in a way many a later Hollywood director would gleefully reproduce, and also split-screen imagery in returning to the tricoleur motif. The best aspect of this is that Gance is still trying here to use his innovation with definite artistic purpose rather than merely showing off – although he’s certainly doing that too.

Here, much like his protagonist finally gaining the keys to the kingdom, Gance revels in being able to step between grandiose surveys of massed human potential and closer, simultaneous views of individuals reacting in fascination and wonder, and both at once. The sight of the men on the march with Napoleon racing forth on his steed on either side of them like an unleashed world spirit gives way to the army storming a town as their first outpost of conquest, whilst their general stands on a hilltop and “plays with the clouds at building and destroying worlds.” Gance finally leaves off with the image of the resurgent eagle, swooping over the heads of the advancing force as they escape on a spree across the world. It’s impossible to deny the power and aesthetic brilliance of all this, even if it is possible to argue with Gance’s romantic vision, his unadorned appeal to French nationalistic propaganda and embrace of his titanic conqueror, despite the interesting and considered codicils he offers before it. A few years later the worst people on earth were on the march under eagle banners, but then again the best were doing much the same thing, and the spirit Napoleon as a film is far more like the latter than the former. In the end the most certain truth is that Napoleon is a relic, a diary, a manifesto, a monument, all depicting a creator acting just like his hero – playing with clouds at building and destroying worlds.