.

Director/Coscreenwriter: Stephanie Rothman

By Roderick Heath

At a time when women directors were still excruciatingly thin on the ground even in Hollywood’s least reputable quarters, Stephanie Rothman forged herself an intriguing place in movie history. Rothman had proven herself a stalwart operative for Roger Corman and his low-budget movie factory at AIP during the 1960s. She made her credited directing debut when she helped patch together a releasable film from a mishmash of footage left after Jack Hill was sacked from a project that involved splicing new footage into a Yugoslav movie, one of many such cunning retrofits Corman’s crew were called upon to perform. With Rothman’s third hand in the pot, the result, Blood Bath (1966), emerged as an incoherent yet tenaciously likeable, free-form collage of images and artistic temperaments. Rothman was given her shot at handling a film in her own right and after her solo debut It’s a Bikini World (1967), she gained a significant hit with The Student Nurses (1970). Rothman followed Corman to his burgeoning New World studio and producer Larry Woolner asked her to make a vampire movie. Rothman and her husband Charles S. Swartz punched out a screenplay built around Rothman’s idea of making a movie centering on a female vampire, a project that would become The Velvet Vampire.

Although it was destined to become her most admired and well-known film, The Velvet Vampire was initially a box office disappointment, and it sped up Rothman and Swartz’s decision to leave Corman’s fold and work with Woolner in setting up a rival production company, the short-live but relatively prolific Dimension Films. Rothman managed to direct three more movies there in between overseeing the company’s filmmaking operations, before her career ran out of steam, and she failed to follow the likes of Francis Coppola, Jonathan Demme, and Peter Bogdanovich into more exalted filmic spheres. Now chiefly associated with horror cinema thanks to Blood Bath and The Velvet Vampire, most of Rothman’s works were sexy comedies, chiefly distinguished by the tense but fruitful way Rothman’s unabashedly feminist ambitions blended with the down-and-dirty prerogatives of genre cinema, working to offer equal-opportunity nudity whilst offering spry examinations of the shifting social more the late 1960s and early ‘70s. The Student Nurses kicked off a successful series for Corman, whilst Terminal Island (1973) looked forward to dystopian tales ranging from Escape From New York (1981) to The Handmaid’s Tale in envisioning a future where death row inmates are stranded in a wilderness prison and a brutally medievalist social set-up quickly evolves and then devolves into outright war between the sexes. Group Marriage (1973) contemplated the possibility of an idyllic polyamorous union between an increasing number of people. If the basis for most of Rothman’s films was the comedy of manners translated for the age of Sexual Revolution, The Velvet Vampire redeploys the same idea in a context where the stakes of conquest are much more alarming.

Rothman quickly announces a real eye with the shot of downtown Los Angeles that opens The Velvet Vampire, a vestigial crucifix jutting high above a precinct of modernist architecture like a remnant of old faith in an otherwise oblivious world. Zoom back to reveal the busy thrum of midday in the city, and then a slow dissolve into the same shot at night, cars and pedestrians becoming ghosts and then fading into oblivion, the buildings readily transmuted into a field of Neolithic standing stones, an arena ready for a primal blood rite. A small squiggle of red strides across the frame upon the pavement: our antiheroine, Diane Le Fanu (Celeste Yarnall). Diane sees a parked motorcycle and correctly anticipates danger. A wild and hairy biker, some escapee of Corman’s The Wild Angels (1967) at war with all civilised mores, quickly obliges as he tackles and tries to rape the chicly dressed lady. But Diane quickly turns the tables, jamming the biker’s own knife into his gut. Diane picks herself up, washes off in a nearby fountain, and casually proceeds on her way. She enters an art gallery where her friend Carl Stoker (Gene Shane) is curating an exhibition, and encounters a young couple, Lee and Susan Ritter (Michael Blodgett and Sherry Miles). Lee and Susan amiably play at being strangers who flirt over the art works whilst trying to fit in with the arty crowd: “I get a lot of sensual energy from it,” Susan comments in regarding a sculpture that resembles the lower half of a bisected female body with legs splayed. Carl introduces them to Diane, whilst old blues man Johnny Shines (playing himself) regales the uptown crowd with elemental tales of evil ladies and demon lovers. Diane invites Lee and Susan out to her home in the California desert with a flirtatious intensity that easily hooks Lee, and the couple, who uneasily fancy themselves swingers, accept the invitation.

They drive out to the remote locale, stopping for gas and directions at a lonely service station, where they encounter anxiously snooty hippy car mechanic Cliff (Paul Prokop), who’s too uptight over his status as a qualified tradesman to stoop to filling up their tank. The station owner Amos (Sandy Ward) reluctantly gives the Ritter directions to the house they’re after, but their car breaks down on the way. Fortunately Diane appears in her dune buggy to rescue them, and spirits them to her house, where she maintains a posh lifestyle with her Native American manservant Juan (Jerry Daniels). Promising to get their car fixed, Diane charms the couple into staying several days, whilst getting Juan to fetch Cliff from the service station. But Cliff quickly learns he’s been called over to be eliminated, and he finishes up accidentally impaling himself upon a pitchfork as Juan chases him about Diane’s garage. Diane introduces Lee and Susan to the environs about her home, including a remote graveyard where her husband is buried, as Diane explains that although she dislikes the desert sun and heat she feels obligated to remain close to his grave, as he was carefully preserved through a method of the local Native American tribal folk. Juan comes from the same tribes, and Diane explains she grew up with him after her parents rescued him as a foundling. But Juan confuses Susan by suggesting Diane saved him when she was already an adult. Diane gives the couple a tour of an abandoned mine that fell into disuse a century earlier after many murders were mysteriously killed, apparently by some sort of feral beast. Susan freaks out when she’s left alone by both Diane and Lee as they stumble about in the dark looking for each-other, and Diane seems poised to attack Susan from the shadows, but is forestalled when Lee abruptly returns. Needless to say, Diane is a vampire.

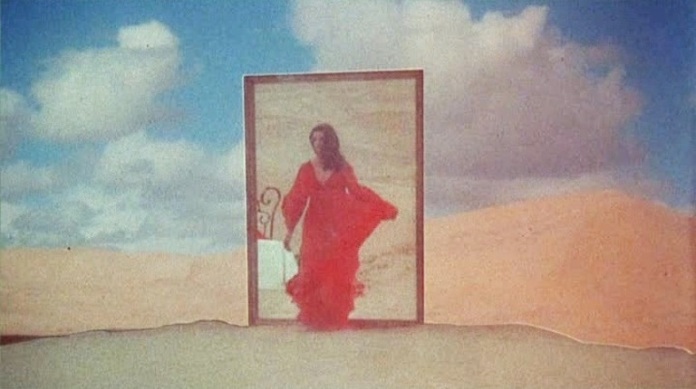

Diane’s designs on Lee are patent, but she slowly unveils her intention to also seduce Susan, as Rothman makes sly sport of the liberated mores of 1971 and their tendency towards double-standards, as Diane practices divide-and-rule between the couple. She takes the direct approach with the husband but makes charged overtures to Susan: “Have you ever noticed how men envy us – the pleasure we have, that only we can have?” Whilst Diane leads Lee off into the secluded aisles of a ghost town to grab his crotch, a rattlesnake slithers upon Susan as she sunbathes, and bites her leg, cueing a moment of sexual frisson as Diane sucks the poison out of her pink, nubile thigh. What neither Lee nor Susan knows, as they bed down for their increasingly strained connubial nights, is that Diane watches them from behind a glass mirror inset in the bedroom wall, measuring their characters, assessing their anxieties, transmitting dreamscapes into their sleeping minds. They both experience the same fantasia in which their bed is transposed into the midst of the desert, gleaming curves of brass and blood red sheets stark against the roiling dunes. Diane is seen in the distance through haze and dust like a Sergio Leone character, only to then step out of a mirror, suddenly switching to a Cocteau film or Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (1964) as interlocutor for protean adventures. The dream, which progresses further each night Lee and Susan spend in the house, unfolds in torpid slow motion, punctuated with liquidinous dissolves, sees Lee drawn out of bed by Diane’s commanding presence, but then replaced in bed by her as she claims Susan by carving a cross upon her chest.

These sequences, startling in their hallucinatory beauty and hearty embrace of surrealist design sharply composed to a degree rare even in the trippiest reaches of the era’s cinema, are surely the essence of The Velvet Vampire’s cult appeal. And yet the entire film is a work of admirable craft and art worked on a low budget and within the parameters of an exploitation film of the early ‘70s zeitgeist and the New World imprimatur. Rothman’s films have gained admiration for the expanse of her efforts to consider the cultural landscape of the day within those parameters, the shifting mores, the quicksands of rapidly evolving laws of sexuality and coupling and the advent of the age of lifestyle as a personal religion. The Velvet Vampire makes mischievous commentary not only on cool-kid gimcrackery but on low budget cinema’s efforts to exploit it, offering up Diane as fashion plate and new age idol, mistress of her domain in her perfectly tailored mod clothes and zipping about in that ultimate period symbol of Californian luxury consumer status in such movies, the dune buggy. Rothman offers Diane as a commanding, intelligent, cultured, motivated woman who, if she wasn’t a ghoul forced to live off other human beings, would stand as an idealised fantasy figure of feminine self-sufficiency. Rothman contrasts her with the Ritters, who both tread the outer edges of caricature at first, with Lee obeying the call of his own dick and Susan, with her high, throaty voice faintly reminiscent of Judy Holliday gone bikini-clad hipster, or perhaps akin to Doonesbury‘s Boopsie getting cast as Van Helsing.

Miles and Blodgett, who had played the hunky object of pansexual affection Lance Rock in Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), are the most awkward aspects of The Velvet Vampire, as both are pretty one-note presences. But their very lack of depth as actors to a great extent suits their characters, with their whiny, edgy, facetious postures as hip and cool young things and appearance as a classical west coast Ken and Barbie set, even as their marriage is badly strained by subtle disconnections, and bit by bit they emerge as well-considered characters. Both retain a certain level of sympathy as we see they’re essentially two babes in the pansexual woods, greedy and needy but fatefully poor at articulating their desires. Susan has a habit of freezing Lee out sexually by rarely being in the mood for his amorous advances, and he acts out by turning over and ignoring her as he goes to sleep. After Susan spies on him and Diane making love in her parlour, he barks in the morning, “All right – I got laid last night.” Ironically, Lee properly committing infidelity actually lets the couple reconnect, in part through Lee’s decision Diane is playing games with them. But Susan can’t entirely resist the chance for payback, and a possible adventure with the alluring Diane, nor can Lee bring himself to resist what Diane is putting down. Meanwhile their host continues to delay their departure by pretending their car can’t be fixed yet even as Lee becomes frustrated he can’t return to the city for necessary business.

Events begin to build to crisis point as Diane finds herself increasingly unable to control her appetites. Her dead husband’s grave has never been filled in, covered instead with a camouflage of wooden boards hidden under sand, so now and then she can lie upon its coffin lid or even cuddle up to his embalmed body stark naked, an image right out of the visual lexicon of the Decadents and Surrealists. Juan, kneeling by the grave in close attendance, is sympathetic as she confesses to him from the pit, “I need more and more now – something is speeding up inside me.” When Juan offers to help by finding her “one of my people” to feed on, Diane reaches up and pulls him into the grave to dine on him. Diane’s tragedy as Rothman sees it lies in her doom to constantly devour anyone and anything that loves her. Rothman grants her the stature of a pining romantic, still mourning her beloved mate a century after his death, but then undercuts it with the ultimate revelation that she killed him less than a week into their marriage through her bloodlust. Diane is also avatar for the forces of colonial exploitation that crashed upon the American landscape, playing Samaritan to Juan, saving him from massacre and starvation, but also fostering him as subservient and finally, casually claiming his life when Diane’s insatiable hunger proves too great. The same fate lies in wait for Lee and Susan, extending to them the illusory possibility of mutual erotic fulfillment, but doomed only to engage in murder. There’s a note here that’s similar to one Rainer Werner Fassbender would sound the following year in The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (1972), in warning of the potential in sexual liberation of reproducing the crimes of dying paradigms by refusing to look beyond the ego’s wants.

Rothman’s tale has telling similarities to a clutch of other movies released around the same time employing the same essential theme, including Hammer Films’ Karnstein trilogy, Jesus Franco’s Vampyros Lesbos (1970), and Harry Kuemel’s Daughters of Darkness (1971), all stories revolving around female vampires with Sapphic tastes. This aspect of the metaphorical had long been visible in the genre since Coleridge’s “Christabel” and Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (Rothman makes the connection between her variations on both Le Fanu’s book and Dracula plain enough with her character names), and suddenly, after a brief and furtive flourish in the mid-1930s with Dracula’s Daughter (1935), had to wait until the easier mood of 1970 to suddenly bloom. The appeal of this small continent of queer-themed vampire dramas, most of which have retained a strong following if not usually free of a touch of smirking nostalgia, lay in the way they made incorporating soft-core thrills easy whilst also appealing to horror fans with overtones of the genuinely transgressive, the crackle of outlaw sexuality according perfectly with horror cinema’s beyond-the-pale status. Where Kuemel’s film lolled in a lush conjuration of retro camp whilst contemplating his vampire lady as ageless, parasitical diva, Franco officially defined his as a reborn misandrist, and the Hammer films played Carmilla as a sort of female, antiheroic James Bond offering to all the chance to both get their rocks off and fulfil their death wish. Rothman presents Diana in yet another key, tracing the outer edges of lesbian desire both more delicately in terms of what she shows but also more directly and challengingly in how she states it. There are no languorous lesbian make-out scenes, and Rothman acts on her credo in eroticising Blodgett’s body as much more than then actresses, but also frames Diane’s come-on to Susan as an outright appeal to come to the isle of Lesbos, kingdom of multiple orgasms.

Islands of peculiar beauty flow by Rothman’s camera from those early frames of the film, with such visions as the frontier graveyard with its crude wooden headstones, and the environs of Diane’s house, where California modern meets Latin manse with plush, décadent overtones. Yarnall’s hypnotic, cut-glass beauty and cool charisma – curiously unexploited by any other filmmakers subsequently – gleams over the brim of her crystal goblets, and burns white against the red Rothman often swathes her in, hovering like a desert rose against sandy environs, or else lounging a naked, pale sylph against her husband’s body. Yarnall, whose best-known role apart form this is probably an episode of Star Trek she guest-starred in, struts across Rothman’s desert landscapes with sombrero cordobés perched upon her head, reminiscent of the way Rothman’s fellow Corman alumnus Monte Hellman costumed Millie Perkins in his desert trip-out, The Shooting (1965), and inhabiting the same role as death incarnated in beauty. Indeed, there’s a curious synergy between Rothman’s approach to her version of horror cinema, with its desert vistas and sense of sun at once stark and hallucinatory, with the vogue for “acid westerns” around the same time, and suggests potential for overlap between western and horror cinema where the few other directors who have tried finding common ground between the two resolutely usually fail utterly.

Likewise Rothman sees no disparity between the open, light-flooded surrounds of the desert and the hard geometric forms of modernism when the film returns to the city: there are wildernesses devoid of human life and those filled with it. Amidst sequences of Diane stalking Susan through bus terminals and malls of LA, Rothman’s eye finds cold abstraction in the rows of telephone booths and escalators, places that seem to mimic the mystical portals and planes of her imposed dreams. Rothman’s eye betrays traces of Michelangelo Antonioni’s imprint throughout, the whole thing could be read as another sun-struck daydream of the protagonists of Zabriskie Point (1970), whilst also mediating between him and the way other eyes like Alan Pakula and Sydney Pollack would read a similar incongruity and alienation in the implacable forms of the new urban landscape. The brief but pathos-charged scenes involving Cliff and his girlfriend evoke the fallout of the Easy Rider (1969) epoch, countercultural exile Cliff desperately trying to stick up for his hard-won status as a mechanic still served up as lunch, and his loyal girl (Chris Woodley ), who swears black and blue that Cliff was off the dope for good, makes a valiant effort to track him down but meets the same fate of being assaulted and sucked dry.

Susan manages to fend off Diane once she finds Lee’s vampirised body in her bedroom, and escapes her villa, fleeing back to LA on a bus only to find Diane has beaten her onto the transportation and silently hovers behind her all the way into the city. Susan finally defeats her tormentor by learning she’s vulnerable to two classical traits of a vampire, fear of the crucifix and pained by strong direct sunlight, and so encourages a mob of spaced-out hippies to aid her in cornering Diane and exposing her, a task the crowd takes to in dissociative enjoyment as if it’s a schoolyard game. Rothman’s cruel sarcasm here sees her worldly and powerful antiheroine, avatar of ages, felled by giggling dopers and crucifixes from a street vendor’s stall, broken by the very real shock of the taboo still wielded by such objects in spite of their mass-commercial debasement, and the devolution of a revolutionary moment and its actors into paltry anti-climax reminiscent less of any Hammer horror finale than of King Kong (1933), which also saw its great monster exterminated by motorised insects. Susan defeats the vampire, but soon finds herself possibly at bay before another, as she visits Carl only to see signs he might well have been Diane’s comrade or acolyte. Perhaps vampirism is about to be the new big thing in bohemia.