.

Creator: Gene Roddenberry

Directors: Robert Butler / James Goldstone / Marc Daniels

Screenwriters: Gene Roddenberry / Samuel A. Peeples / George Clayton Johnson

By Roderick Heath

As a boy in Texas in the 1920s and ‘30s, Gene Roddenberry was a voracious fan of the sci-fi and pulp storytelling of Edgar Rice Burroughs and E.E. ‘Doc’ Smith, stirring the desire to become a writer. After stints as a US Army pilot during World War II and a civilian pilot for Pan Am after, his third crash convinced him to try another profession. He joined the police whilst also pursuing his writing ambitions, blending the two when he landed a job as technical advisor and then writer on the TV show Mr. District Attorney. Roddenberry soon found himself in demand, eventually quitting the cops in 1956 as his career stepped into high gear working on shows including the popular Western series Have Gun – Will Travel, defined by roving heroes and self-contained episodic storylines, and showed equal talent for wheeling and dealing behind the scenes. Some of the quirks of personality and fortune that would define Roddenberry’s professional legacy were already manifesting, particularly frustration in constantly developing and pitching series ideas no-one wanted to produce, and getting sacked from the show Riverboat before even a single episode was made, because of Roddenberry’s fierce objection to the producers’ wish to not feature any black actors on the show despite being set on the Mississippi in the 1860s. On shows he ran or tried to make happen in the early 1960s, Roddenberry met many actors he would later reemploy, including Leonard Nimoy, Nichelle Nichols, and DeForest Kelley.

Since the mid-‘50s Roddenberry kicked around variations on the idea of a contained ensemble drama set aboard modes of transport, including an ocean liner and an airship, adding increasingly fantastical elements and the idea of a multi-ethnic ensemble. Taking inspiration from models including the 1956 film Forbidden Planet as well as Smith’s Lensman and Skylark series and the spacefaring stories of A.E. Van Vogt, Roddenberry merged his various concepts into the one project, revolving around the exploratory adventures of a starship. He added the idea of a lead character based on C.S. Forester’s omnicompetent naval hero Horatio Hornblower. The name of the starship, Enterprise, allowed Roddenberry to reference both the early swashbuckling days of the US Navy and the awesome modern aircraft carrier that represented Cold War America’s military and technical might. He called the proposed series Star Trek. Roddenberry gained the support of Lucille Ball, a close friend whose Desilu production company urgently needed a successful show, and took it to various network chieftains, pitching it as “Wagon Train in space” to make it seem more familiar. NBC decided to back a pilot, selecting one of Roddenberry’s scripts, “The Menagerie.”

Rechristened “The Cage,” the pilot was shot in late 1964, and sported Roddenberry’s lover and future wife Majel Barrett as the starship’s first officer Number One, and Nimoy as a vaguely satanic-looking alien officer named Spock. Jeffrey Hunter, former acting protégé of John Ford whose career had ironically been stymied after playing Jesus in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1963), was selected to play the Captain, Christopher Pike. “The Cage” failed to win over executives and test audiences, but unlike so many of Roddenberry’s projects NBC clearly saw potential as they agreed to produce a second pilot, albeit infamously telling Roddenberry to “get rid of the alien with the pointy ears,” and swapping out Hunter’s intense and thoughtful captain for someone with a little more swagger and bravura. For the second pilot the network chose a script Roddenberry had developed with Samuel A. Peeples, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” and this time paved the way for the show’s eventual premiere in 1966. Oddly, “Where No Man Has Gone Before” would be the episode screened third: the first broadcast episode proved instead to be “The Man Trap,” written by George Clayton Johnson. The show had many similarities to Irwin Allen’s series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and had a rival in Allen’s next production Lost In Space, which had a more juvenile tone but a similar basis in a spacefaring team encountering character often existing in the blurred zone between sci-fi and outright fantasy. Much like its major rival in TV sci-fi annals, Doctor Who, the show suffered through initial low ratings to surge as a surprising cult hit for the first two years of its three-season run, although the real key to its persistence in pop culture proved to be its popularity in syndication in the 1970s.

“The Cage,” “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” and “The Man Trap” therefore all present inception points for the series and varying stages of drafting for its eventual, settled template. “The Man Trap” was probably selected to screen first because of its relatively straightforward monster-on-the-loose plot, and also because it sported Kelley as the ship’s Chief Surgeon, Leonard ‘Bones’ McCoy, not yet cast on “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” and so orientated viewers to the essential line-up more quickly. “The Cage” was eventually, cleverly repurposed for the show on the two-part storyline with the title of “The Menagerie” restored. “The Cage”’s negative was hacked up for use on the show, and the complete version was thought lost. Roddenberry pieced together the full episode combining the colour footage used in “The Menagerie” and a black-and-white workprint, the form in which I, and others, first saw it on video, before a pristine colour print was later recovered. One irony of this is that I think I’ve seen “The Cage” more than any other Star Trek episode, and it stands very close to being my favourite iteration of the entire property, only rivalled by certain episodes of the various series and movie entries like Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982). “The Cage” stands somewhere between the divergent tones of the original series and its eventual successor Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-93), but also exists in its own peculiar pocket, a place of surreal delights. The re-emergence of the pilot even did much to set the scene for the reboot represented by The Next Generation, a hint this universe could sustain different modes and resonances.

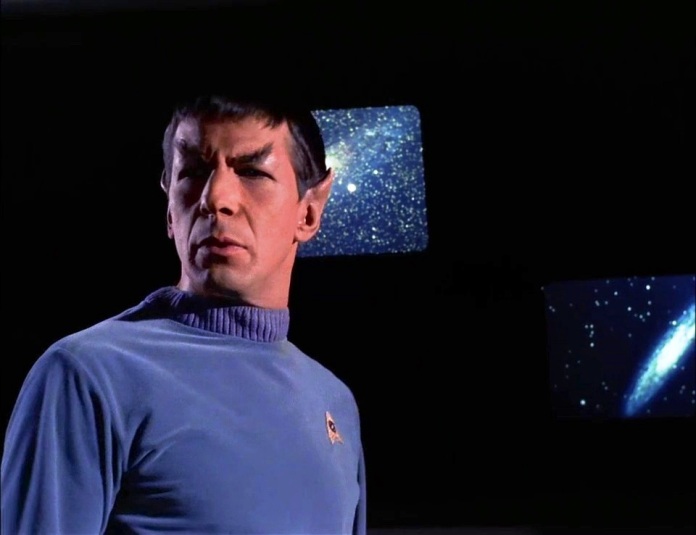

Many familiar aspects of the show were already in place for “The Cage,” including the Enterprise, the presence of Spock and the general infrastructure of the series’ fictional lore and tech like beaming and phasers, the boldly colourful designs and cinematography, and Alexander Courage’s inimitable theme music. The differences however suggest a whole different version of the show existing in a ghostly parallel dimension to the familiar one. Spock, whilst already invested with his familiar look (although it would be toned down afterwards), isn’t the nerveless rationalist of renown but a rather more youthfully impassioned and demonstrative crewman; the trait of chilly intellectual armour is instead imbued upon Barrett’s Number One. McCoy isn’t yet present, nor is Nichols’ Uhura, James Doohan’s Mr Scott, or George Takei’s Sulu. Indeed, one particularly interesting aspect of “The Cage” is that its emphasis is more on gender diversity than racial, with Pike caught between the diverse potential love interests of Number One, and the younger, more callow Yeoman J.M. Colt (Laurel Goodwin), who would be supplanted in the show proper by Grace Lee Whitney’s rather sexier Yeoman Rand. Roddenberry had also left the door open in his scripts to making Spock and the Chief Surgeon female, although eventually in addition to Nimoy John Hoyt was cast as the doctor, Phillip Boyce.

Star Trek arrived as a summation and condensation of Roddenberry’s eminently commercial yet singular artistic personality, one reason perhaps why it immediately overshadowed everything else he did: some creative people are destined, and doomed, to arrive at one vital crystallisation of their imagination. Roddenberry’s experience whilst still a very young man as a leader responsible for lives had a deep and obvious impact on his storytelling, and sometimes used the show to explore aspects of his experience, like the episode “Court Martial,” which evokes a crash Roddenberry had during the war and its aftermath. Ironically, Roddenberry would be caught constantly trying to reassert his control over the property and confronted by the way the input of other creative minds would sometimes prove to understand the nature of its popularity better than he did himself, most particularly when Harve Bennett and Nicholas Meyer rescued the film series it birthed in the 1980s. Roddenberry’s thorough steeping in the kinds of character relations and story basics familiar in TV thoroughly permeated Star Trek, in the panoply of ethnic and job title archetypes, the thematic and narrative similarities to the Westerns he’d worked on, and the basics of how the crew of the Enterprise work and live together.

The opening images of “The Man Trap,” the very first glimpse of the Star Trek aesthetic TV audiences would actually see, envisions the planet M-113 as a desolate place scarcely trying to look like something other than a set, with Fauvist skies and soils and Ozymandian ruins. It’s a psychological environment of the kind many a Surrealist painter laboured to describe, plucked out of the collective unconscious. A place at once wild and filled with traces of vanished grandeur. This edge of stylisation, of the dreamlike infusing the very texture of the universe, is one of the original show’s most specific qualities and one sadly missing from its many progeny. Aspects of the signature look had already been mooted in “The Cage” where Pike and Spock discover and ponder strange blue flowers that vibrate with alien music, although the landscape was more prosaic with a grey overcast sky and rocky forms like a stretch of the American desert. “Where No Man Has Gone Before” offered visions of the remote Delta-Vega, an outpost of super-technology resembling an oil refinery grafted onto an alien shore.

The sense of landscape was one area where the show took clear inspiration from Forbidden Planet, which offered similar vistas and the concept of the id made solid and animate. But the emphasis on rugged and far-flung environments was also clearly part of the show’s inheritance from the Western, including John Ford’s iconic use of Monument Valley, a place the show never visited, preferring the more economicaly adjacent Vasquez Rocks. Star Trek hinges upon evoking and inflating to newly fantastical scale the same sense of awed fascination with the raw bones of the American land, the scarps and mesas and jagged geometries of the western deserts, along with the same uneasy mix of celebration in freedom and wealth of space and conflict over the viability of colonialist enterprise, as drove the Western. Often this was interspersed with depictions of deceptively placid Edenic zones where the flowers are beautiful and deadly.

Roddenberry was already beginning to play the subversive games the show would become famous for. Early in “The Cage” Pike explores his general depletion in spirit and mind from years of commanding the Enterprise with the sympathetic Boyce, who’s rather older than McCoy would be and yet less crusty and combative, instead offering a clear-eyed wisdom more like the characters in The Next Generation. Number One’s stern and heady veneer toys with the familiar figure of the eminently meltable iceberg akin to the female scientists seen in ‘50s sci-fi films like Them! (1954) and It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955), but notably the episode doesn’t undercut her as a figure of command, as Number One has to lead the crew after Pike is kidnapped. The pilot was directed by Robert Butler, an ultra-professional TV director who would go on to an odd and sporadic feature career including making movies for Disney like The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1970) and Hot Lead and Cold Feet (1978) as well the trashy action-thriller Turbulence (1997). “The Cage” sees the Enterprise, exploring unmapped regions of the galaxy, attracted by a rescue beacon to a desolate planet dubbed Talos. Believing they’re rescuing the crew of the Columbia, a spaceship that vanished years earlier, Pike leads a party down the planet, where they encounter the bedraggled survivors and their makeshift encampment.

Pike meets the strikingly beautiful Vina (Susan Oliver) amongst their number. She leads him away from the camp on the promise of showing him something interesting, only to deliver him into the arms of a race of bulbous-skulled aliens who knock him out with a gas gun and take him down into the earth via an elevator hidden within a mesa. Pike awakens in a cell with a transparent wall, and the Talosians tell him he’s to remain part of their zoo of fascinating specimens. The Talosians have immense gifts of telepathy, able to plant completely convincing illusions in the minds of others: apart from Vina all the survivors prove to be mirages who vanish once Pike is secured. The Talosian who oversees the zoo, The Keeper (body of Meg Wyllie, voice of Malachi Throne), tries to influence Pike into taking Vina as a mate and accepting his fate to breed and produce a race of servile humans who can help the Talosians, who have become incapable of any kind of practical activity, restore their planet. Attempting to rescue Pike, Number One and Spock set up a powerful energy weapon fuelled by the Enterprise’s engines and try to blast open the Talosian gateway, but seem to fail.

Pike is carefully characterised as a captain with a sterner, steelier exterior than his eventual successor, but also quickly reveals to Boyce his sense of guilty responsibility for losing several crewmembers on the barbarian planet Rigel 7 and his recent tendency to pensively contemplate quitting his job and pursuing less demanding and more profitable pursuits. This contradicts the one steady constant of his successor James T. Kirk’s character, his complete and unswaying dedication to his ship: Kirk’s angsts, once explored, would rather tend to revolve around the threat of losing the ship, his authority, and his friendly comrades. The episode hinges around Pike’s sense of purpose and energy being restored by having to fight for his freedom and identity. The Talosians force him to re-experience a battle he had on Rigel 7 with a hulking warrior, the Kaylar (Michael Dugan), but this time in defence of Vina, outfitted as a classical damsel in distress. Pike eventually grasps a contradiction, that base and primitive emotions like murderous rage can stymie the Talosians’ psychic powers, and fosters them in himself whilst aware this means stripping away his own civilised veneer. “The Cage,” “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” and “The Man Trap” all share distinct fixations and story elements, particularly with psychic powers and chameleonic, reality-destabilising talents. Dualism and the dangers of deceptive appearances would become obsessive themes for the show, and a great deal of its genre-specific ingenuity would be expended in finding new angles to explore them.

This also connects to an aspect the Star Trek franchise has long been running away from with a guilty smirk, the pleasurably dirty secret of the original show, as an artwork preoccupied by and deeply riddled with sexuality. Down to its curvy-pointy designs and title fonts, this pervasive erotic suggestion was part of its essential texture as a drama aimed at the protean zone between the theoretical and the psychological. The way Spock was amalgamated with Number One gives a faint credence and explanation for the oft-fetishised erotic arc many viewers often felt existed between Kirk and Spock. In “The Cage” the subtext is scarcely buried, as the Talosians overtly try to appeal to Pike’s libido by reconstructing Vina in various fantasy scenarios as different kinds of woman, from lady fair to be protected, partner in an idyllic Earth marriage, and as a green-skinned dancing girl of the notoriously lusty Orion peoples, performing for Pike in his own private harem. Vina plays along with such manipulations for motives that only become clear at the episode’s end. These scenarios are all drawn from Pike’s experiences or the fantasies and potential lives he confesses to Boyce in their early conversation. Again, “The Cage” delves further and more boldly into such conceptual conceits, offering a plotline that’s also in part a witty meditation on Roddenberry’s lot as a TV maker, sketching scenarios in hunting for appeal to the audience’s needs and desires, the correct balance of elements needed to persuade and enthral. “Almost like secret dreams a bored space captain might have,” one of Pike’s illusory guests in his harem notes, making explicit the idea we’re seeing common idyllic fancies made flesh.

“The Cage” also deploys the prototypical metatextual and mythopoeic storytelling that would permeate the show, with its myriad references to classical mythology and Shakespearean drama, and the constant games with the characters’ sense of their essential natures and their perceptions of reality in a way that also allowed the actors playing the parts to explore other aspects of their talents. At its best Star Trek seemed to genuinely seek to pattern itself after classical mythology as functioning at once as rigorous storytelling with a hard and immediate sense of form and function, whilst also operating on a level of parable and symbolism, incorporating a dreamlike sense of alien worlds and bodies as charged with qualities the viewer knows and feels with a strange new lustre. This approach would, in the series’ lesser episodes, manifest in a succession of corny political parables (“The Omega Glory”) or clumsily revised myths (“Elaan of Troyius”). “The Cage” also marked the first of many allusions to Plato’s parable of the cave, in regards to the limitations of knowing reality through the senses, and the motives who those who might manipulate others through this disparity. True to the subsequent show’s fame for incorporating social critique, there’s also an implicit self-critical note for Roddenberry and television in general, in the way the Talosians’ basic aim is to make Pike sit still and consume fantasy in order to make it easier to manipulate him into doing the bidding of and fulfilling the needs of controlling masters. Seeds for darker and more explicit variations on such a theme, like John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) and the Wachowskis’ The Matrix (1999). With the added sting that the Talosians themselves have become addled consumers of the fantasies they generate, cut off from action just as surely as their captives.

“The Cage” reaches its climax as the Talosians forcibly beam down Number One and Yeoman Colt and present them as alternative mates so Pike can take his pick. The Keeper notes their divergent qualities and potentials like a particularly dry car salesman whilst also simply forcing Pike to recognise the way his mind has, consciously or not, always cast a sexually assessing eye over his female crewmembers, and vice versa. This move by the Talosians proves their downfall however, as the women were brought down with their phasers, and whilst these seemed to do no damage the Keeper tries to retrieve the discarded weapons. This gives Pike a chance to take him captive, and he threatens to throttle him if he doesn’t release them. The dispelling of imposed illusion allows the captives to see the actual, devastating damage their weaponry made upon the Talosian infrastructure. But Pike is also forced to see Vina in her true physical state: terribly injured when the Columbia crashed, she was rescued and repaired by the Talosians but at the time they had no understanding of what a human should look like, leaving her a twisted and haggard travesty, and only the Talosians’ abilities to conceal this gave her any chance of finding companionship. This forlorn punchline is amplified by the Talosians themselves, recognising that with the humans proving too intransigent to serve, they’ve lost their last chance to save their species. The episode does leave off with a grace note as the Talosians recreate Pike in illusory form to give Vina company.

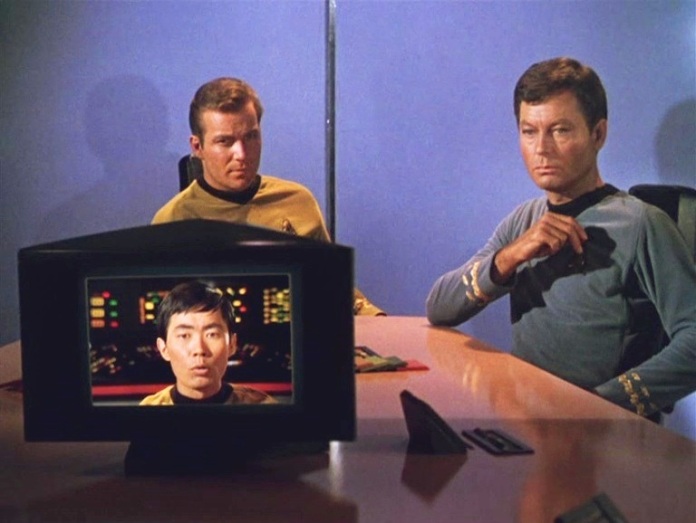

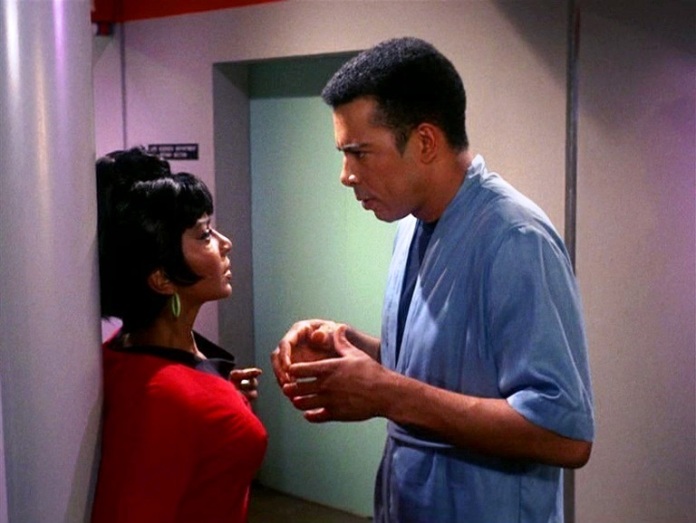

The revised version of the storyline seen in “The Menagerie” offered the events of “The Cage” as a flashback set 13 years in the past, with a different actor cast as the now-disfigured and paralysed Pike for the present-tense scenes. “The Menagerie” had Spock commit mutiny for the sake of honouring his old commander, taking him to Talos so he can live with Vina and believe himself restored to his unbroken self, a surprisingly clever bit of repurposing even if it dispelled much of “The Cage”’s surreal intensity. The image of Vina as the Orion dancing girl became one of show’s most iconic images, often featured in the end credits of episodes, encapsulating the show’s mystique on many levels. For the second pilot shot nearly a year after “The Cage,” Roddenberry had to find a new lead as Hunter had dropped out. Eventually, the Canadian former Stratford Festival alumnus turned minor Hollywood star William Shatner was cast as Captain James Kirk, whose middle initial, glimpsed upon a conjured tombstone, is given in the episode as R. rather than the eventual T. Far from being introduced at a low point or riven with doubts and guilt like Pike, Kirk arrives as the starship captain entering his prime, confident, quick in mind and body, the perfect man of action who’s also the rare man of intellectual poise. Other essential roles and performers were added, including singer and actress Nichols as Uhura, the communications officer, James Doohan as chief engineer Montgomery ‘Scotty’ Scott, and George Takei as Sulu, initially a science officer but later recast as the ship’s helmsman.

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” and other early series episodes revolve most fixatedly upon Shatner as Kirk, dominating the rest of the cast. Eventually the essential relationship of Kirk, Spock, and McCoy would form, with Spock representing reason and McCoy instinctive humanism, and Kirk constantly trying to balance the two. This shift was informed in part by the impact made upon the showrunners by the way many female viewers surprised them by preferring Spock as the alluringly cool and thoughtful heartthrob, a conspicous contrast to the type of James Bond-inspired man’s man so common in pop culture at the time, although the potential appeal of Spock was already plainly in the show’s thoughts in the earliest episodes. A certain caricature of Kirk has emerged in popular lore as a brash and chauvinistic he-man, pushed hard by J.J. Abrams’ 2009 cinematic reboot. The caricature sadly excises Kirk’s other, more vital and nuanced traits, and even his image as a womaniser neglects the edge of frustration and pathos, even tragedy that so often attached to his romances. To be fair, Kirk as a character often suffered from the way the show would make him into whatever any given episode’s writer needed, sometimes presenting a nuanced philosopher-king and at other times a reactionary cold warrior. Eventually some of the later films, particularly when Nicholas Meyer was writing him in The Wrath of Khan and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991), would unify his facets successfully.

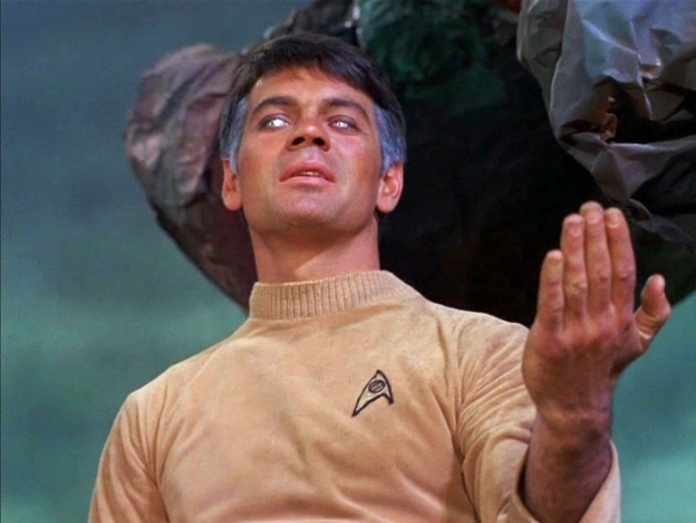

Shatner’s presence as Kirk also represented a compromise between Roddenberry and network executives as to just what the hero of the show should be, schism written into his very being. For the time being Shatner had to impose unity upon the character, developing Kirk’s edge of almost self-mocking humour alongside his edge of hard will and imperious ego, mercurial wit of mind and body invested in his signature, wryly challenging smile, signalling his refusal to take things too seriously, a mechanism that allows him to function in situations that might crush others. Shatner matched his voluble physicality to his inimitable speaking style with its elastic, often sprinting cadences and juddering emphases, to describe the way Kirk has mastered the difficult art of making his masculine vigour and the racing motor of his intellect work in concert. In “Where No Man Has Gone Before” he’s contrasted by a similar type, Gary Lockwood’s Gary Mitchell, serving as the Enterprise’s helmsman. Their eventual conflict has an aspect of doppelgangers clashing, Mitchell symbolising what might result if the side of Kirk that allows him to function as a commander, his sense of innate exceptionalism in authority, was ever encouraged to overwhelm the rest of his character. And, by extension, delivering the same lesson to the audience, all presumed to see themselves to some degree or other in Kirk.

Despite his frequent frustration with Shatner’s Kirk, the character certainly engaged Roddenberry’s pervasive interest in what made for an ideal leader figure, a notion he must surely have been contemplating since being pushed into such a role as a young man and then serving in institutions tasked with service and discipline, making friction against the side of his personality concerned with humanitarian and egalitarian ideals. The show managed to offer reflection on the conceptual tension in the episode “The Galileo Seven” where Spock, obliged to take command when he and other crew crash land on a strange planet, finds himself bewildered when he does everything right according to his sense of logic and expedience only to find the other crew detest him for his tone-deafness to their emotions, whereas they trust Kirk implicitly. In the same way, Kirk was required to help get the audience invested however much he cut against the grain of Roddenberry’s ideals. The bulk of representatives of the Federation and Starfleet hierarchies apart from the Enterprise crew are portrayed as pompous and oblivious blowhards through the original series, shading the show’s mythologised utopian streak in a manner that might well have been informed by Roddenberry’s personal observations about rank, as well reflecting Roddenberry and team’s stormy relationship with their often aggressively bemused network bosses.

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” counters Butler’s stark and dreamy approach with more forceful and flashy handling from James Goldstone, who go on to have a feature film-directing career dotted with some underregarded movies like Winning (1969) and Rollercoaster (1977), and strong guest star support from Lockwood and Sally Kellerman. The episode’s title proved so keen in describing the essence of the proposed show it was quickly incorporated into Kirk’s opening narration. Despite the crew’s nominal assignment on a five year exploratory mission to “strange new worlds” and seek out “new life and new civilizations,” the Enterprise would nonetheless often be found performing more prosaic tasks in well-travelled areas. “Where No Man Has Gone Before” does at least start with the Enterprise preparing for a daring tilt at the edges of the known, whilst also repeating “The Cage”’s gambit as the ship picks up a signal leading to the wreckage of a long-lost ship, this time the USS Valiant, and recover what proves to be an ejected flight recorder. The first moments of “Where No Man Has Gone Before” offer immediate definition of Kirk and Spock’s divergent yet magnetised personalities as they’re glimpsed playing three-dimensional chess, kicking off a running joke in the show where Kirk always beats Spock at the game despite the latter’s vast intellectual prowess, through Kirk’s illogical tactical genius. Joining them on the bridge as an alert is called are the Chief Surgeon Dr Mark Piper (Paul Fix) and shipboard Psychiatrist Dr Elizabeth Dehner (Kellerman).

Spock delves into the recovered record of the Valiant’s end and through garbled passages discerns the ship was driven beyond the galaxy’s edge. There it struck a powerful energy field that killed several crew and left one strangely affected. The Valiant’s ultimate destruction seems linked to enigmatic requests for information about ESP abilities the Captain made to the ship’s computer, before the Captain made the ship self-destruct. Deciding to trace the Valiant’s path in the hope of finding more wreckage, they encounter the same energy field at the galactic frontier. The barrier almost fries the Enterprise and Mitchell and Dehner are both struck down by shocks, seemingly correlated with the degree of latent ESP ability both have been measured in, with Mitchell the most affected, left with a bizarre silver glaze over his eyes. Taken to the sick bay and watched over by Piper, Mitchell seems otherwise unharmed and reveals rapidly growing psychic abilities, allowing him to consume the ship’s computer files at speed and revealing telekinetic power too. Eventually it becomes clear Mitchell is evolving into something very powerful and dangerous, and in a desperate attempt to keep him from taking over or destroying the ship Kirk spirits him to Delta-Vega, a planet supporting an automated lithium refinery, to maroon him. Dehner also develops the silver eyes and incredible power, and aids Mitchell in freeing himself.

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” mediates the tones of “The Cage” and the settled show: Shatner-as-Kirk retains some of Pike’s restraint and pensiveness, although by the episode’s end he’s more thoroughly and specifically designated as an action hero. Where “The Cage” allowed Pike to be identified in a sardonic manner with tiger-in-a-cage intensity and thwarted strength, “Where No Man Has Gone Before” sees Kirk taking on the nascent superman in a fistfight regardless of the long odds. Spock is now firmly defined by his devotion to logic, but not yet stoic dispassion. The climax, in which Kirk battles Mitchell who’s now powerful enough to refashion pockets of reality, sees the rogue mutant conjure up a grave for Kirk complete with carved tombstone, a semi-surreal touch of a brand the show would regularly invoke, in a universe filled with incongruous sights in far-flung surrounds. The weird sexuality likewise is contoured into the direct flow of plot. Mitchell and Dehner, initially defined by gendered polarity – he’s aggressively flirtatious, she’s haughty and heady so Mitchell dismisses Dehner as a “walking freezer unit” – are soon united in new, exceptional identity, their glazed silver eyes signifying a perverse bond in their post-human state. That bond is ultimately ruptured when Kirk makes desperate appeal to Dehner as he battles Mitchell: Dehner aids him in attacking Mitchell and briefly nullifying his powers, at the cost of her own life.

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” maintains a muscular, cinematic force and it’s easy to see why it, rather than “The Cage”, ultimately provided the right blueprint when it came to getting Star Trek up and running. Though not nearly as layered and intriguing, it fulfils the necessary task of presenting this particular wing of sci-fi dreaming as one defined by potent, active characters and forces representing a dialogue between stolid settlement and wild possibility, fantastical yet familiar-feeling in many basic aspects. Goldstone taps the image of the silver-eyed Mitchell for moments of creepy punctuation, as in a fade-to-black that leaves only the eyes glowing, and when he looks into a security camera and Kirk realises he is looking back at him through the camera. Mitchell was the perfect antagonist to lay down this blueprint as a normal man stricken with godlike talents, underlining the emotional meaning not only in Kirk having to kill him but in presenting vast new stages of drama through a human-sized conduit.

Lockwood and Kellerman are valuable presences in their one-off roles, clearly a cut above the usual run of TV supporting actor of the day, and Lockwood’s presence gives it an incidental connection to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a film that would take up aspects of Star Trek’s inquisitive reach and push further. Spock would be the singular archetype the show invented rather than augmented for pop culture, but he’s still an evolving and relatively muted figure, perhaps partly because Roddenberry had gone out on a limb to keep him in the series. Nimoy himself was still trying to nail down his characterisation, his voice pitched about a half-octave higher than the inimitable monotonous drawl he would develop. Spock nonetheless is already serving his chief function as the character who offers piercingly unblinkered analysis to Kirk, as when he tells him in no uncertain terms he must either maroon Mitchell or kill him whilst he still can. And yet the very end of the episode sees him admit to Kirk that he too feels a sense of a pathos at Mitchell’s destruction, a first sign that Spock’s surface tension hides undercurrents running deep and fast. Part of the legend of Star Trek revolves around Shatner and Nimoy’s rivalry: supposedly no less a personage than Isaac Asimov advised Roddenberry to overcome Shatner and Nimoy’s ego duels by making their onscreen characters inseparable.

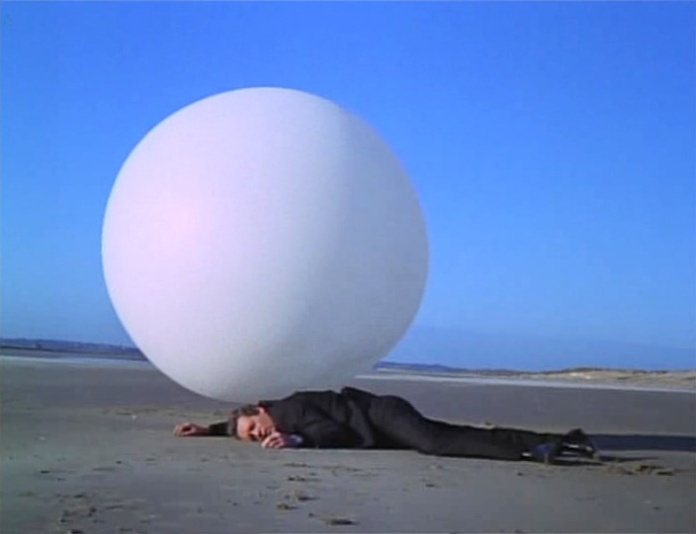

“The Man Trap” iterates a plot the show would return to regularly, most notably in “The Devil on the Dark.” That episode would take the show’s nascent humanist spirit further in presenting the lurking monstrosity as entirely misunderstood, whereas in “The Man Trap” the alien creature is a more straightforward threat, although still voted a degree of sympathy as a forlorn survivor of a decimated species driven by its predatory needs, much like the Talosians. The theme of besiegement by an alien monster in “The Man Trap” echoes Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks’ The Thing From Another World (1951), and indeed restores the idea of a shapeshifting monster Nyby and Hawks excised in adapting John W. Campbell’s story. But Roddenberry and his team were trying to philosophically and practically reconcile that film’s propelling contemplation of prudently vigorous militarism in conflict with coldly inquisitive science. As he did for the two pilots and most of the first season, Courage wrote the incidental music, and his spare, sonorous, Bernard Herrmann-like scoring helps invest “The Man Trap” with eerie beauty, although Roddenberry didn’t like it, one of the first signs the show’s wellspring didn’t entirely grasp what made it good.

Appropriate to the plucked-from-the-Id aesthetic, the monster in “The Man Trap” is a sci-fi spin on the incubus/succubus figure, a creature that takes on the appearance of former lovers and friends to entice those it meets, plundering the libidinous and needy backwaters of the heroes’ psyches for its own purposes. Again, like many episodes subsequent, “The Man Trap” establishes the common refrain of exploring the lead characters’ emotional baggage and busy yet always foiled love lives, here most particularly in the case of McCoy, who sees the creature as Nancy (Jeanne Bal), an old flame who married the archaeologist Professor Crater (Alfred Ryder). The Enterprise is performing a routine visit to check up on the couple as they document a long-dead civilisation, and Kirk, McCoy, and a redshirt crewman, Darnell (Michael Zaslow), beam down for that purpose. McCoy sees Nancy as he remembers her, whilst appearing to Kirk as grey-haired and weathered as he less sentimentally expects, and to Darnell as someone else entirely, a sex kitten he met on shore leave. When Darnell goes off with the creature, he vanishes, and his crewmates later find his body, and medical analysis reveals he’s been entirely drained of salt. Other crewmen die in the same manner, and ‘Nancy’ takes on the form of one of her victims, Green (Bruce Watson), in order to be beamed up onto the Enterprise where pickings are plentiful. Uhura sees the creature as a fellow black crewmate who almost gets hold of her.

“The Man Trap” therefore hinges on the same conceit as “The Cage” in externalising the characters’ inner angsts and fantasy lives through the device of role-playing. The note of forlorn emotionalism is amplified as Kirk and Spock eventually uncover the truth, that the real Nancy was killed by the creature years before and the vampire has maintained a sickly symbiotic relationship with Crater. He’s kept it alive with his encampment’s stock of salt whilst it maintains Nancy’s appearance to please him. Crater’s remnant, lingering affection even for the mere semblance of Nancy is given further weight by his awareness as a scientist that the creature is the last survivor of the toppled civilisation he’s been studying, a parasitic monster that’s also pitiful. The creature stirs a similar emotion of heedless protectiveness in McCoy, one that almost prevents him from saving Kirk’s life in the climax as the creature turns on the Captain. “The Man Trap” establishes McCoy as a man so driven by his sense of humanity as a palpable thing that it can sometimes cloud his judgement, to the equal and opposite degree to which Spock would so often strike him as psychopathically detached. Crater and ‘Nancy’’s relationship reaches an inevitable end as the scientist is killed by the increasingly desperate creature, although the episode foils the potential tragic punch by having this occur off-screen.

When Kirk tries to convince McCoy that ‘Nancy’ is using him the creature mesmerises the Captain, Spock tries to intervene, making a brutal assault on the creature which McCoy sees only as violence perpetrated on Nancy until the creature easily swats the Vulcan aside. But McCoy still can’t bring himself to gun down the creature until Kirk starts screaming as the creature begins to drain him. “The Man Trap”’s director Marc Daniels would handle many episodes of the series with concerted energy, including perhaps the most famous episode, “Space Seed,” which would sport the first appearance of Ricardo Montalban’s nefarious supervillain Khan. The most intriguing aspect of these first three efforts at defining Star Trek is observing how much room they left to manoeuvre for the series, dramatically speaking, and the first half of the show’s first season, whilst erratic in quality, offered various characters and relationships to be enlarged upon at leisure. The second screened episode, “Charlie X”, starts with a memorably odd musical sequence in which Uhura improvises a song teasing Spock, as he plucks his Vulcan lyre, for his weirdly enticing and provocative coldness.

Part of Star Trek’s odd afterlife as a series ultimately lies in the way it never quite lived up to such promise, even though even at its silliest and campiest it was never less than highly entertaining. “The Cage” and “Where No Man Has Gone Before” have gravitas and a relative lack of the formulaic aspects that would both define the show in its halcyon days and ultimately retard its growth. One example of this would be the way the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triumvirate became central, resulting in most of the other characters being left sidelined beyond performing their stalwart crew functions. Famous as they rightfully are for offering multicultural role-models, figures like Uhura and Sulu nonetheless finished up largely wasted for great stretches. Meanwhile, despite the show’s seemingly limitless purview, a certain repetitiveness of theme and story set in, particularly once the show’s budget was cut and the scope reduced to battles against intruding forces on the Enterprise, and the episodic format prevented any appropriate sense of the characters evolving along with their universe. This proved the ultimate foil for the original Star Trek, one that finally helped kill it when it should have been entering its prime, but also informed the eventual revival and great success of a franchise. Today, it seems, the world has caught up with what Roddenberry originally offered. The most recent iteration of Star Trek, Discovery, has revisited “The Cage” and a series revolving around Pike, Spock, and Number One and their adventures together has been announced. Now there’s a cosmic irony even Spock might offer a smile for.