.

Directors: Michael Curtiz, William Keighley

Screenwriters: Seton I. Miller, Norman Reilly Raine

By Roderick Heath

In Memoriam: Olivia de Havilland 1916-2020

It’s been said that old Hollywood conquered the world in large part because it contained the world in small, a provincial place ruled by some very parochial ways but where people from around the globe, driven by their strange talents and the tides of history, congregated to manufacture the fantasy life of billions. Few films embody that success so perfectly as The Adventures of Robin Hood. The most famous of action heroes, Errol Flynn, alongside his most beloved on-screen partner Olivia de Havilland, in a splashy production from the usually budget-cautious Warner Bros., The Adventures of Robin Hood doesn’t just fail to age, but seems utterly outside the flow of time, exemplifying a way of making movies and pleasing an audience rooted in a specific moment, but managing to inhabit a rarefied realm, becoming its own myth. The Adventures of Robin Hood was originally intended as a vehicle for James Cagney, and a semi-remake of the 1922 film that had starred the first great screen swashbuckling hero Douglas Fairbanks , even carrying over co-star Alan Hale reprising his role as Little John. Cagney’s quarrels with studio boss Jack Warner delayed the film. Captain Blood (1935) established Flynn in the meantime as Fairbanks’ heir, and De Havilland as his ideal leading lady.

William Keighley, a respected theatre director who had come to Hollywood with talkies and made some excellent, streetwise thrillers with Cagney like “G” Men (1935) and Bullets or Ballots (1936), started the film. But Keighley soon fell behind schedule and turned in such lacklustre action footage Warner quickly replaced him with Michael Curtiz, who had directed both Captain Blood and The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) with Flynn and De Havilland. It’s hard to imagine three more different people than Curtiz, Flynn, and De Havilland in terms of temperament and background, and yet they were all people who had come a long way from where their lives had started, collaborating on a film about a culture-specific hero who nonetheless finds echoes and avatars the world over, and it almost seemed they born to play the parts they did in making The Adventures of Robin Hood. Flynn, the Hobart-born public school brat turned fortune-hunter who slinked back to Sydney after adventuring around New Guinea, was trying to settle down when he suddenly found himself thrust into an acting career playing Fletcher Christian in Charles Chauvel’s In The Wake of the Bounty (1933) because he seemed to embody the role, swiftly catapulting him in Hollywood’s direction.

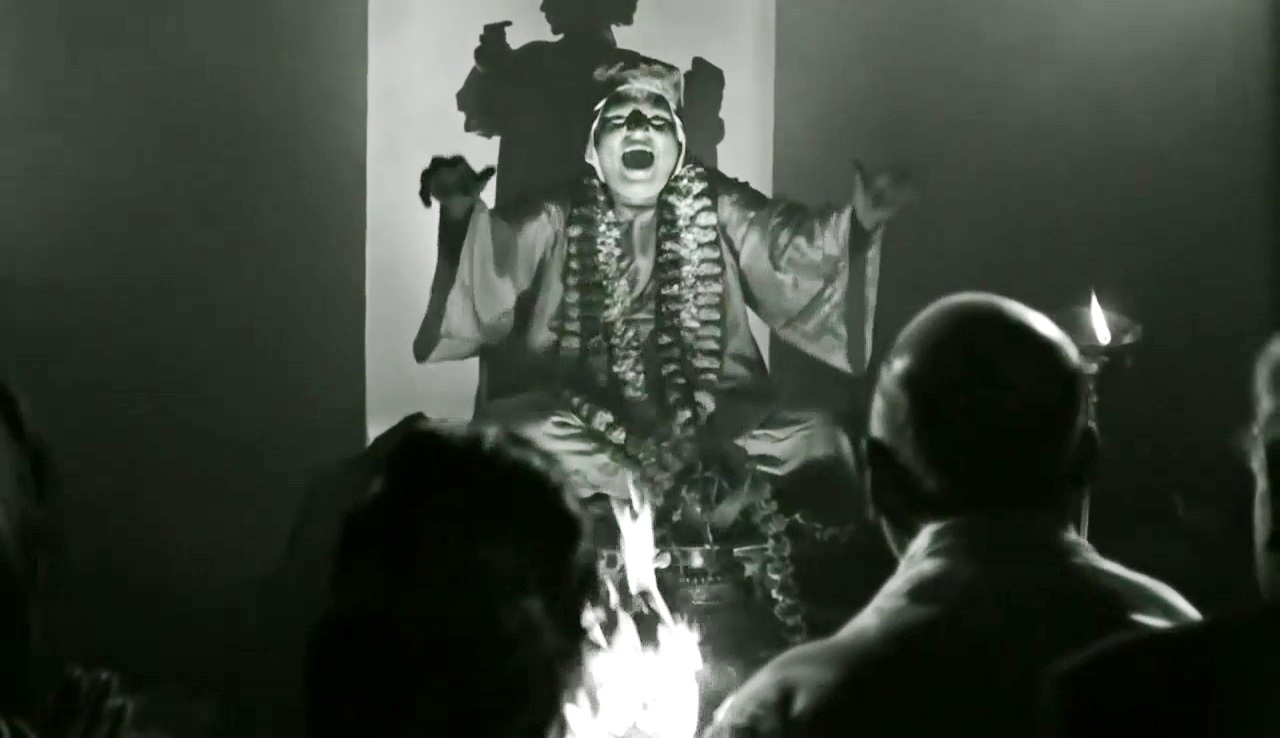

De Havilland, progeny of a posh yet unstable family, cousin to aviation pioneers and born in Tokyo, but fated to grow up in southern California, the shore she, her mother, and sister washed up on. Like her Maid Marian she rebelled against a despotic guardian and followed her own path, catching eyes in amateur theatre productions despite wanting to be a teacher, and within a year found herself starring in Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935). Curtiz, born Manó Kaminer in Budapest in 1886, was the son of a Jewish carpenter and an opera singer, who as a young man roamed around Europe as an actor and circus artiste, picked up languages and talents in a wayward manner, and grew into a man famous for his extraordinary energy and bravura, eventually ploughing it all into cinema. He became an Olympic fencer and directed Hungary’s first feature film all in the same year. Curtiz, wounded on the Russian front during his World War I service, went back to filmmaking and was already a hardened filmmaking veteran when his Biblical epic The Moon of Israel (1924) caught Jack Warner’s eye, and quickly became a pillar of Hollywood film.

Much of The Adventures of Robin Hood’s richness stems from the way it manages to walk a very fine line, offering a highly stylised vision of medieval England, with colossal sets and visual textures that mimic medieval tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, and Victorian-era illustrators like Howard Pyle and Arthur Rackham, in attempting to entirely conform to a certain storybook ideal of ye olden days. But this is counterbalanced by coherent undercurrents of darkness and urgency, even a strange kind of realism, flowing under the glossy Technicolor. Amidst a sprawl of movies released in the last two years of the 1930s, The Adventures of Robin Hood reflects the world around it, worried as it is about dictatorial coups and contending with the clash between official order and the rage of the dispossessed. As a film it speaks to the experience of the Depression and rising Fascism, whilst also affecting to deliver the viewer from all such cares in a florid dream of a legendary past. Robin as a hero is offered as a scarcely concealed guerrilla warrior and social radical, speaking out loud what was merely subtextual in Warners’ ‘30s gangster movies in presenting a hero for the economically oppressed and socially betrayed in thieving and offending the powerful, loaned a fig leaf of acceptability by the way he fights in the name of a just but displaced order rather than to supplant it.

Early scenes immediately establish the drama in those essential terms. The opening depicts a town crier announcing that King Richard the Lionheart has been taken captive by Leopold of Austria, who demands a huge ransom for the King’s release. Prince John (Claude Raines), Richard’s brother, uses his captivity as an opportunity to start working towards snatching his throne, relying on his strong support from men like Nottingham potentate Sir Guy of Gisbourne (Basil Rathbone), the Bishop of the Black Canons (Montagu Love), the county’s High Sheriff (Melville Cooper), and other barons, and enrich himself and his cronies by pretending to collect the ransom. Much the Miller’s Son (Herbert Mundin) is offered as the emblematic everyman, homely, modest, and desperate, as he shoots dead a deer on the fringes of Sherwood Forest for food despite the royal edict banning anyone but the king from hunting them. Caught in the act by Sir Guy and his squad of knightly goons, Much protests the impossibility of making a living with all the restrictions on the peasantry, particularly given the pervasive social divide between the ruling Norman elite and the Saxon populace.

Much is saved from a quick hanging by the intervention of Sir Robin of Locksley (Flynn), hunting with his friend Will of Gamwell (Patric Knowles). Robin is a Saxon nobleman, and rather than see Much executed for his crime, instead tells Sir Guy that he killed the deer and wards off his own hanging with the threat of his formidable skill with a longbow: “Are there no exceptions?” Robin queries as he aims his shaft at Sir Guy’s face. At a grand banquet in Nottingham Castle, Sir Guy plays host to Prince John and royal ward Lady Marian Fitzwalter (De Havilland). The assembly of smug-ugly Norman nobles discuss the increasing resistance to taxation, and John reveals he’s removed Richard’s regent and is taking over the reins of government. The banquet is interrupted as Robin appears with the dead deer draped over his shoulders, swatting guards with the carcass and parading into the banquet hall to dump his gift of venison on the table before John and his allies. John, at once amused and goaded by Robin’s calculated show of insolence, readily plays along in offering Robin a chair and food and listening to Robin’s boastful declaration of intent to start fermenting resistance to John’s regime.

This sequence plays as Robin’s true introduction, defying the Norman elite in all its pomp and happily playing the rogue, prodding his foes to make their play of violence before he retaliates with his immense gifts for fighting. The classical motif of the unwelcome visitor interrupting a feast, often Death incarnate as in Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, is given a radical new twist as the visitor is rather the embodiment of insurrection and class war. Robin instantly becomes the idealised rebel and a fantasy projection figure, the man we all wish we could be in standing up to bullies of every stripe, so confident in his abilities and justifications that he can place himself in the very eye of all worldly might and still find his advantage. Prince John’s signal for a guard to hurl a spear into the back of Robin’s chair is the official declaration of war. Robin immediatley makes his foes regret missing as he uses every weapon at his disposal, from banquet tables to his slashing sword and bow, able to climb to a high gallery in a few deft gymnastic moves and rain death down upon opponents whilst everyone churns about in panicked confusion. The filmmaking and Flynn’s athleticism conspire to make it seem actually possible that one man can create such a furore, the action laced with symbolic immediacy: Robin literally upturns the tables and social mores and wallops his opponents with them, before gaining high ground to fire his stinging judgements.

Robin battles his way out and reaches Will, waiting with horses in the castle courtyard, and the two men dash off into the nocturnal Sherwood Forest with Guy’s men in pursuit, where they give the hunters the slip. This sequence, nominally a very straightforward bit of action staging repeated in dozens of Westerns and swashbucklers, nonetheless exemplifies the peculiar mystique of the film. Robin and Will’s flight takes them through shadowy forest aisles scored by slanting beams of moonlight and shimmering streams, frenetic motion countered with evocations of nature as embracing, near-mystic in its affinity with the fleeing freedom fighters and a plunge into a dreamlike realm fitting for folk heroes. Much of the rest of the film unfolds as a series of set-piece vignettes depicting Robin forming his band of Merry Men and battling the Normans. Transferred intact from folkloric tales are Robin’s encounters with Little John (Alan Hale), as each man refuses to give way to the other on a log crossing a river, and Friar Tuck (Eugene Palette), both of which see Robin and the other man testing each-other’s character and fighting skill before making friends and alliances. Robin loses his fight with Little John, who proves more adept with staff fighting than Robin, but prevails over Tuck, whose fencing skills are infamous.

The Adventures of Robin Hood repeats elements that worked in Captain Blood, whilst offering a simpler plotline and sustaining a more successfully balanced tone, taking the recourse into raw mythology as a good excuse to locate the primary ingredients for a great action-adventure movie. One particular recurring but also augmented idea was again offering Rathbone as dark mirror to the straight-arrow Flynn hero, a figure who looks enough like Robin to be a relative, is his rival in love as well as quarry, and something akin to what Robin would be if he lacked any degree of social conscience or ethical fibre, or indeed perhaps if Robin had simply been born on the agreeable side of a social divide. Sir Guy is promoted to foregrounded villain to contrast both Prince John’s effete egomania and the hapless chicken-hawk postures of the Sheriff, giving Robin a truly equal and dangerous foe and helping to flesh out the way the film emphasises the social conflict not simply as one of rich and poor but one arranged along ethnic lines. “He’s a Norman of course,” Marian acknowledges as Prince John presses her to see the good reasons behind marrying Sir Guy, illustrating this hegemony as an internecine phenomenon, even as Robin relentlessly sets about illustrating that such an elite cannot long survive the determined cooperation of the Saxon citizenry, a body that can easily be read as any oppressed faction conceivable.

Writers like Walter Scott and Nathan Pyle, who imbued much of the shape upon the folkloric template that now stands as familiar, nonetheless didn’t emphasise the notion of Robin as a specific kind of rebel against a particular historical regime: it was The Adventures of Robin Hood that made this seem canonical. Robin in his earliest ballads and tales had been defined as a yeoman – a sort of middle-class in medieval English society – but he later became an expelled nobleman. The process of remaking Robin in this fashion might well have reflected the way the character stirred anxiety over the idea of class warfare, but it opened up interesting political ramifications in turn, making Robin the exemplar of how social order is supposed to work, those entrusted with power and responsibility using it for the benefit of the people rather than exploiting them as illustrated by most of the other noble characters. A key early montage, showing word going out amongst the commoners to meet Robin in Sherwood and him swearing his followers to a creed and purpose, evokes folk memories of Alfred the Great rallying his people in the wilderness for a resurgence, and a host of other historical likenesses. Like many Hollywood films depicting English history in the ‘30s and ‘40s, there is at once a jaunty appeal to a romanticised sense of that history but also a definite nudge towards making the hero seem a proto-American – Flynn’s odd mutt of an accent allowed him to inhabit a blurred identity in that regard, his clipped phrasing suggesting good breeding but his yawing tones hinting at new world shores.

The romance of Robin and Marian depends upon the inherent sexual tension in the situation of the lady of the castle falling for the upright yet officially degraded and morally tarnished protagonist, a ready-made metaphor for a presumption about male-female relations once considered axiomatic. Marian’s initial detestation of Robin, clearly already stricken through with electric erotic awareness, manifests as she haughtily contends with his daring and impudence, and also carries political meaning, particularly in their famous exchange: “Why, you speak treason!” “Fluently.” The introduction of Marian into the Robin Hood folklore came relatively late in the day and might have stemmed from attempts to mate the gritty, parochial English tales with a French pastoral tradition and chivalric romances, Marian a figure associated with May Day and natural rejuvenation just as Robin himself embodied the dichotomous freedom and danger of the forest. Marian was initially a shepherdess and possibly a prostitute who nonetheless swiftly ascended the social ladder to become a figure from the upper aristocracy. Perfect for Flynn and De Havilland who seemed to inhabit by natural selection the roles of freewheeling male and well-bred lady who represent the possibility of social reconciliation, through transcending class barriers and gendered courtesies.

In immediate terms for the film, this means that De Havilland’s Marian is predestined to melt daintily yet passionately as her love for Robin grows, a love that requires a singular transformative event to finally gain true expression. This comes when Robin and his men ambush a convoy ferrying plunder to another district, led by Sir Guy and the Sheriff, and including Marian and her aged but spirited nurse Bess (the eternal Una O’Connor). The Merry Men expertly manage to surprise their foes and take the nobles captive, obliging them to watch as the guerrilla warriors feast and celebrate and stow away the recovered fortune for Richard’s ransom. Robin takes Marian into the forest and introduces her to people sheltering with him, a pathetic mass of survivors of torture and deprivation, forcing Marian to see the reality of Prince John’s regime and the inevitable result of a social divide. Marian falling for Robin then is also explicitly an act of political awakening. Jack Warner was anything but a progressive hero, but the style of movie he fostered at Warner Bros. in seeking out an audience to appeal to became a consistent brand, with realistic scenarios and characters in their gangster movies and rugged thrillers and working class melodramas. Despite its historically remote lustre, The Adventures of Robin Hood and some of Flynn’s other swashbuckler vehicles would, wields the same sense of struggle by a victimised or degraded group fighting for their rights and defying power.

Prince John accidentally knocking over a wine goblet in the second scene sees red dripping on the floor in mimicry of the blood he’s about to spill, segueing into a brief montage of scenes depicting the tyranny descending as merchants and farmers are plundered and punishment applied to anyone who resists. This flourish is repeated later in the film to more intense effect as the Norman knights double down in their ruthless assaults on the citizenry, sadistic goons unleashed to amuse themselves with a level of brutality that’s surprising when considered aside from the rest of the film as one man is hung up by his thumbs, others lynched from trees, another chained and humiliated and forced to watch his daughter being raped by a squire. There’s a needling potency to the film’s evocation of the period it portrays, despite the storybook colours and high spirits, as generally a place of horror and exploitation. Except, of course, that in this second montage of cruelty and suffering, Robin is on the warpath. Normans are cut down mid-chortle by Robin’s assassinating arrows, with a wonderful little detail when the knight molesting a tavern owner’s daughter takes an arrow in his back, the zip of the shaft extinguishing a candle’s flame. One of Robin’s arrows even skewers his own arrest warrant as Sir Guy moves to sign it in his council chambers, warning the Normans no place is safe from his infinite cunning and freakishly great aim. In these scenes Robin is transformed into something more than human through not showing him aiming or firing his shots, bolts coming even where it seems impossible, man swiftly becoming myth.

The Adventures of Robin Hood’s script was the work of two of the canniest screenwriters of the day, Seton I. Miller, who had written several of Keighley’s films and would revisit this kind of swashbuckler material in a more overtly campy and metaphorically erotic vein with Henry King’s The Black Swan (1942), and Norman Reilly Raine, who had penned The Life of Emila Zola (1937) and would later write King’s marvellous A Bell for Adano (1945). By comparison to many modern films where smart-aleck dialogue comes on as an end itself, the twists of wit in Seton and Raine’s script help drive on the troika of plot, character, and atmosphere, like Prince John’s enquiry to Robin, after he spits out a hunk of roast duck, “Have you no stomach for honest meat?”, to Robin’s retort, “For honest meat, yes, but no stomach for traitors.” The Adventures of Robin Hood is the kind of film more recent takes on the mythology try explicitly to offer negative-image revisions of, aiming instead for a darkly textured and authentic lustre, seen in works like Kevin Reynolds’ Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood (2010), and Otto Bathurst’s Robin Hood (2018). Certainly aspects of The Adventures of Robin Hood, like Will’s brilliant red robe and lute-strumming and the bawling matey laughter of the Merry Men, have a touch of camp that can make a modern audience snort in sarcasm.

And yet most revisionist takes stumble when it comes to apprehending a deeper, less obvious level of realism, missing the way Keighley and Curtiz expertly present the social background of the mythology and depict their version’s dimensions as parable. Scott’s version was ambitious in trying to refashion Robin into a plebeian figure and use him to describe the birth of democratic feeling, although the lumpy story got in the way. By contrast, Curtiz and Keighley’s film sees the historical detail and its interrelationship with folklore unfold smoothly, and connects with the scale of the production to give the film its monumental quality. The montages of beastly Norman depredations laid down a template for portraying tyranny that would be easily repurposed in films made during the oncoming war, and indeed there’s also a strong similarity to Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky, made the same year, a film that likewise reaches back into the dim past and a legend-encrusted hero battling monstrous opponents with implications about the looming moment, albeit with a more explicitly propagandistic purpose. Robin himself is presented completely against the grain of the contemporary pattern in his lack or neurotic or antiheroic traits. Instead the film constantly underlines how Robin and his comrades’ laughing opposition is their most authentic weapon. Robin’s refusal to let his foes intimidate him, to let them use the power of fear over him, and by extension those he protects, robs from them the pompous certainty that they embody and bestow harsh reality.

Flynn’s Robin is the essential movie hero, able to seem big-hearted even when engaging in warfare, blessed with endless physical vigour and spryness of mind to match. Flynn embodied, thanks to his life experience, a peculiar blend of formative forces and traits, a life-greedy, knockabout man of action with gentlemanly bearing, a persona his films depended upon. Flynn didn’t receive much validation as an actor until near the end of his career, and he aggravated some on set through his breezy approach. But the way he holds the screen, with his precise sense of gestural effect and ability to vary his personality through degrees from satirical jester to awakened killer, reflects a naturally intelligent and expressive performer. Robin’s promise to Prince John in the banquet hall to “organise a revolt – extract a death for a death,” commences a precisely balanced campaign of resistance, measured and fair, even as he’s obliged to fight by different rules that allow his enemies to paint him as a mere brigand. Robin’s calculated risk-taking at both the banquet and later an archery tournament he knows full well has been staged to capture him reflects his consciousness that it’s precisely his acts of defiance, his willingness to take such chances, that fuel his following, the only way he can provoke an equally superhuman sense of empowerment in ordinary people. In the same way the character exists for the audience in the real world as a figure of emulation, so he also exists within the film.

Goodness is specifically demarcated throughout the film by humour. Robin sometimes comes close to an all-action Groucho Marx in his general, breezy contempt for authority and social niceties and ready line in barbed quips, whilst the japes and teasing and boisterous laughter that permeate the interactions of the Merry Men, presenting an idealised version of masculine camaraderie, contrasting the coldly malicious undertones to Norman sarcasms and the outright enjoyment many take in dishing out brutality. The ambush on Sir Guy’s treasure convoy is the central sequence of the movie and a glorious piece of filmmaking that both illustrates Robin and his band’s method and captures their metaphorical appeal too. The guerrillas are filmed shimmying up the twisting branches of the forest trees and confirming to the bowers as if transformed into woodland creatures, before raining down on their startled opponents, the entire forest suddenly alive with manpower charging in to overpower the Normans, the editing carefully diagramming the assault as one coming from all vantages. One irresistible shot has the Merry Men charging at the camera and bounding over it (with the aid of a hidden trampoline), possessed of athletic vigour and gallant wit to the point of becoming an unstoppable natural force.

The sequence reaches its climax as Sir Guy and the Sheriff realise they’re entirely surrounded and outmatched, at which point they hear Robin’s highy entertained laugh. The bandit chief is glimpsed high in a tree, swinging down upon a vine to land on a rock and declare, “Welcome to Sherwood, my lady!”, the embodiment of rascal charm and daredevil prowess, mocking his foes with dynamic showmanship and ironic hospitality. All of this is wrapped in mischievous energy and a faintly sarcastic heroic tenor by Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s scoring. The band’s triumph in capturing the convoy allows them an opportunity for a mighty, convulsive feast where the captured Normans are forced to don peasant rags and a bandit proclaims immortally, “To the tables everybody and stuff yourselves!” Flashes of bawdy comedy come as Much flirts with Bess despite admitting to never having had a sweetheart, to which Bess crows she’s “had the bands five times myself,” and Much answers Bess’s suggestion he says the same things to every woman who tickles his fancy with, “I’ve never tickled a woman’s fancy before.”

Korngold’s music is regarded as one of the best scores ever featured in a movie. Certainly it’s one of the most influential, with just about every big orchestral score for a blockbuster today owing something to its example. Korngold was a musical prodigy who had impressed Gustav Mahler with a cantata he wrote at the age of twelve. Despite his serious musical reputation for his operas and orchestrations for other composers, Korngold is easily most famous today for his film scores, first coming to Hollywood to create an adapted version of Felix Mendelsohn’s score for Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and his work followed on the heels of fellow Mahler acolyte Max Steiner’s score for King Kong (1933) in expanding Hollywood’s understanding of how a sound film score could work, woven deeply into the rhythmic structure rather than simply punctuating scenes. Korngold then agreed to score Captain Blood and laid down the template for his floridly emotional and evocative soundtracks to a string of swashbucklers, music that worked in part through the complete resistance to any modernist impulses. Although his work for The Sea Hawk (1940) is arguably a more textured and painterly effort, his scoring here is the more perfectly attuned to the visuals. The banks of pealing trumpets and surging strings paint the emotional extremes of heroic warfare and intimate romancing, with a remarkable level of orchestrated detail apparent, reaching a particularly high pitch of bombastic greatness during the build-up to the climax as Prince John’s coronation procession enters Nottingham Castle, the surging strains capturing both the gilded grandeur and the undercurrent of peril.

Most importantly, Korngold’s music helps to unify the film’s episodic structure, dragging it from one set-piece to the next as each section of the movie presents a small drama that contributes to the overall story whilst taking care to illustrate a vital aspect of the folklore. Robin’s choosing of his path segues into the process of assembling allies, before the attack on the convoy sees the Merry Men at a zenith. Robin’s capture at the archery tournament is a moment where his daring and brilliance prove self-defeating, but also crystallises Marian’s ardour and obliges her to pick a side. The last act kicks off when King Richard (Ian Hunter) and his retinue turn up dressed as monks in a Sherwood tavern, having escaped captivity, presenting hope for an end to the tyranny but also providing his brother with a chance to have Richard assassinated and take the throne without hindrance. The archery tournament is another great scene that revolves around the game of concealment and revelation Robin and his enemies feel almost honour-bound to play with each-other: the notion of suckering Robin in with the possibility of the reward of a golden arrow granted by Marian comes not from Sir Guy but the cannier if craven Sheriff. Robin, posing as a tinker with a disguise so amusingly paltry it suggests he might have inspired Superman’s bifocals, enters the tournament despite his companions’ worries.

The editing by Ralph Dawson blends with Korngold’s music in making the tournament, a montage-like sequence, build nonetheless with ingenious dramatic cadence to a crescendo, with Curtiz throwing in canted camera angles and radical shifts in perspective, a mobile camera surveying the archers and rhythmic cuts, to create a scene that still feels remarkably fluid and modern whilst unfolding in manner you scarcely notice. Robin sets the seal on his legend when, faced with a seemingly unbeatably good shot from his final opponent with his arrow dead centre on the target, takes aim and splits the arrow with his own. But Robin is unable to slip the net this time as he’s caught and thrust before the triumphant Prince John, Sir Guy, and the Sheriff, with Sir Guy dealing out a slap to Robin’s face, but the Sheriff, trying the same gesture, gets Robin’s boot in the belly. Sentenced to death, Robin is flung into a dungeon, but Marian, who knows Bess has been seeing Much, obtains the password to meet with Robin’s lieutenants in their favourite tavern and, after assuring them through making a vow at Tuck’s insistence that she’s utterly in earnest, suggests a way for them to save Robin’s life. This involves a daring assault on Robin’s hanging, giving Robin a chance to jump onto a horse and flee with his friends for the great main gate to Nottingham, where upon Robin expertly foils pursuit by sabotaging the city gate’s portcullis with improvised gymnastics, realised thanks to some show-stopping stuntwork.

Robin climbs the ivy – not a euphemism – to Marian’s chamber in the castle to thank her, allowing Flynn and De Havilland to realise their chemistry even in playing by most decorous rules, the perfect gallant and the ideal lady nonetheless dedicating themselves not only to an illicit and illegal love but also to continued political mischief. De Havilland would go on to win two Oscars and prove herself one of the smartest actors of her era, but her roles opposite Flynn as the genteel damsel were the bedrock of her career, partly because they seemed to suit her so perfectly. De Havilland in real life was the proper young lady whose own strength of character kept taking people by surprise, most fatefully when she battled Warner over her contract and established a precedent that emancipated many stars like her. Marian resembles her in being underestimated for her looks and breeding but keeps proving her very real moral fibre, to the point of being arrested after overhearing Prince John and his cohort plotting Richard’s assassination and trying to get warning out. As with her role as Melanie in Gone With The Wind (1939), De Havilland’s lady fair parts depended her capacity to play characters who could seem cloying or icy or witless if handled badly, but De Havilland was able to present as inherently decent. Although a long way from any sort of action heroine, De Havilland’s Marian nonetheless provides her own kind of valour, eventually finding herself in the same position as Robin a few reels earlier where she is tried by Prince John and his cadre and sentenced to death, unleashing a fearless tirade at the usurper and his cronies with a show of steely character that justifies and exemplifies the ideal of nobility, and comprehending the Prince’s intention to have her executed with baleful comment on the depths of his arrogance.

Despite the run of success director and star had together in their collaboration, which would continue with films like Dodge City (1939), The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), and The Sea Hawk, Curtiz and Flynn disliked each-other intensely, and some of the films’ energy seems to stem from the volatile relationship between the pair. Flynn was probably one of the few men in Hollywood who could match Curtiz’s relentless energy even as they turned it to different ends, the hard-living Flynn versus the work-loving Curtiz, and there was also the little matter of Flynn being married to Curtiz’s ex-wife. On screen at least, Flynn readily became the projection of Curtiz’s bravura and romantic impulses. Something of Keighley’s imprint is still apparent on the film: the portrayal of Prince John as an entitled and vainglorious but sardonic and formidable figure, rather than a skulking fiend, has some similarity to Monty Woolley’s overbearing critic in Keighley’s later The Man Who Came To Dinner (1941), and the almost holistic sense of social structure echoes Keighley’s anatomisation of such in Bullets or Ballots (Miller had also written that). The long, surveying camera tracking shots in the early banquet scene suggest something more like Keighley’s sense of theatrical integrity than Curtiz’s carefully composed mise-en-scene.

Nonetheless I find it very hard not to see The Adventures of Robin Hood as ultimately a Curtiz film. Curtiz was the ideal studio-era director, a strong stylist who knew how to run a movie set, who could readily contour his talents into the production system and tackle a wide swathe of genres. Curtiz regarded his assignments from on high less as vexing chores than as challenges to his professional and aesthetic touch, his workaholic drive so reliable Warners set up a special unit just for him to use. But patterns still emerge from his oeuvre. There are inevitable connections despite Curtiz’s late arrival on the film with his other swashbucklers and with Casablanca and its follow-up Passage to Marseilles (1944), most particularly in the preoccupation with heroes in exile contending with political tyranny applied on a victimised population. Curtiz would often return to the theme of an artist, or an analogous fixated figure, driven on by his gruelling commitment through varying shades of heroism and antiheroism. Curtiz worked through this preoccupation in his horror film Murders in the Wax Museum (1933) and dramas like Four Daughters (1938) and Young Man with a Horn (1950), remaking both George M. Cohan and Cole Porter in his own image for Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) and Night and Day (1946), and mediated it through such rovers and warrior-poet characters as Robin, Rick Blaine, The Breaking Point’s (1950) Harry Morgan or The Egyptian’s (1954) Sinuhe, men who experience extremes of their societies and their own natures to soul-cracking degrees, degrees only a creation like Robin can traverse without injury. Such characters are driven to achieve a certain perfection in their personal arts and crafts, which indeed Robin exemplifies this by feeling obligated to perform at peak despite the danger involved because that is what he is.

Curtiz’s trademark style provided a variation on the German Expressionism that had infused cinema in the 1920s, a style he appropriated as a light veneer of style rather than an obsessively suggestive texture. Curtiz’s version offered clean and spacious realms and minimalist sets but with declining stages of décor and performance within his frames, and careful use of light and shadow offering a dimension beyond the literal. Most famous is his recurring flourish of shadows playing upon walls, as in the finale here where Robin and Sir Guy fence, dancing across a chamber in Nottingham Castle, their very corporeal exertions suddenly transformed into something abstract and legendary, and achieving an effect close to animation. The Adventures of Robin Hood proved Curtiz’s first colour film, but was readily able to make his touch work in the new medium. Indeed, The Adventures of Robin Hood marked a radical expansion of what colour could achieve, with cinematographers Tony Gaudio and Sol Polito and the Technicolor overseers W. Howard Greene and Natalie Kalmus making use of all eleven Technicolor cameras built up to that point. There’s some anticipation of the hyperbolic colour effects found in Gone With The Wind in a shot like where Saxons are being hung from a tree at dusk, Expressionist technique in the foreground and fauvist hues in the distance. But the colour textures are generally diffused to give the storybook-like visuals an extra veneer of faded charm.

The precision of the casting down through the layers of the film as another of its multivalent joys, backing up the strength of the leads with actors who nail down the iconographic personas of their roles with quick, deft strokes, from Rains’ leonine smarm to Rathbone’s angular aggression and hood-eyed sexual menace, Palette’s gruff vigour and O’Connor’s cawing pluck, Hunter’s majestic largesse and Hale’s vivacity: the film makes space for them all and more, keen to the give and take of energy this kind of storytelling needs. Much’s ride at Bess’s desperate request to warn King Richard, after Marian is taken prisoner and Prince John sends an assassin after his brother, builds to a terrific fight scene whilst still sustaining the fairy tale lustre, as Much ambushes the killer as he crosses a stream, lethally slashing blades and splashing water glistening with steely texture in the Technicolor amidst dappled summery surrounded. This inverts the comedic tone of Robin’s battles with Little John and Friar Tuck, the struggle in the water pointedly taken up by one of Robin’s acolytes and this time played for history-changing stakes. The outcome is left on a cliffhanger as a dissolve leaves the fighter locked in a death match. Soon Will comes across the wounded but victorious Much and takes him back to Robin, who is already paying unwitting host to Richard as the King, in maintaining his monkish guise, has been robbed and then offered shelter by Robin.

The colour pays off most memorably here as Richard unveils his royal livery in all its blazing splendour of red, gold, and white under the black cassock, stirring Robin and the Merry Men to kneel in awe and homage. Korngold’s scoring also helps make this moment emotionally and aesthetically moving, as the withheld promise of order and justice is suddenly personified and announced like dawn – putting aside all knowledge about the historical Richard, of course. This revelation is the key to the climax as Richard and Robin lead their forces in disguise as monks under the neatly compelled Bishop of the Black Canons (what a name!) and manage to interrupt Prince John’s coronation. Robin and Sir Guy split apart from the great battle that consumes the banquet hall for their duel. The frenetic swordplay of the many warriors is punctuated by comic relief as Much, trying to be useful despite his wounds, hiding in a nook and trying to swat Normans with a mace, asides that keep the tone from becoming swaying too far in either pole of goofy or dour. Robin and Sir Guy’s battle contrasts the wild melee in the hall by instead becoming a deadly dance, moving through cavernous halls, up and down staircases and around vast curving barbicans, space that scarcely makes more sense than anything in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), albeit a dreamscape inhabited not by ghouls but doppelganger incarnations of good and evil.

The climax depends not just on Flynn and Rathbone’s skill and daring, but on their capacity to act in motion, particularly Flynn’s ability to depict Robin indulging himself to a degree even whilst fighting tooth and nail with Sir Guy, even going so far as to waste a chance to spear him and giving Sir Guy his sword back after he loses it so as not to spoil the match, in large part because his aim is not to slay Sir Guy but to find and free Marian. That is until Sir Guy violates the unspoken rules by trying to keep Robin pressed against a wall, whilst pulling out a dagger to stab him. The underhanded move plainly offends Robin by the way his eyes flash in anger and spasmodic alarm, aware the game as it’s been played is at an end and big boy rules now apply: Robin slays Sir Guy within a few seconds. Curtiz repeats a trick from Captain Blood to more succinct and iconic effect as the surrendered weapons of the defeated John partisans are piled up, and Richard holds court with the riff-raff who had saved his throne, granting Robin Marian’s hand and making him a Baron. A happy ending is also deliverance from social duty, as Robin performs a last sleight of hand as he and Marian slip from the congratulatory pile-on and offer their gratitude from the gate before scurrying off to private, connubial bliss, the shutting of the castle doors closing the movie. Likewise, The Adventures of Robin Hood bows out supremely justified.