.

Director: John Schlesinger

By Roderick Heath

The modern world’s fascination with the lives of the rich, pretty, and famous has become ever-more gluttonous. The online age has only engorged the commodification of prying, speculating, envy-mongering and schadenfreude-enabled rubbernecking offered by tabloids and trash magazines, even as we often collectively posture in deploration at the invasion of private life and the reduction of human sensibility to a series of declarative headlines. There’s almost always a strange disparity of attitudes apparent in the way the “public at large”, that amorphous beast, absorbs such grist. We constantly project a rotating series of attitudes onto celebrities and public figures, classifying them variously as monsters, victims, creatures above common human concerns or transgressors, all according to value systems that we ourselves pay lip-service to whilst of course wishing for such exceptional status. John Schlesinger’s Darling purposefully mimics the nominal structure of a tabloid article to try saying something substantial about the kind of person almost nobody takes seriously.

The lousy last couple of films that capped off John Schlesinger’s career were a sorry comedown for one of the brightest talents to emerge from the British Free Cinema movement of the early 1960s. But apart from a couple of misjudged works, Schlesinger’s career run from his debut, 1962’s A Kind of Loving through to 1985’s The Falcon and the Snowman is evergreen in quality and fierce in creative compulsion. Something that’s quite distinctive about his best films, even his adaptations of heavyweight literary classics like Far from the Madding Crowd (1967) and Day of the Locust (1975), is the energy they give off, which feels as if they’re being lived from moment to moment rather than carefully crafted, which they surely are. Darling, a quintessential slice of Swinging ’60s flash and cynicism, won Julie Christie an Oscar for Best Actress.

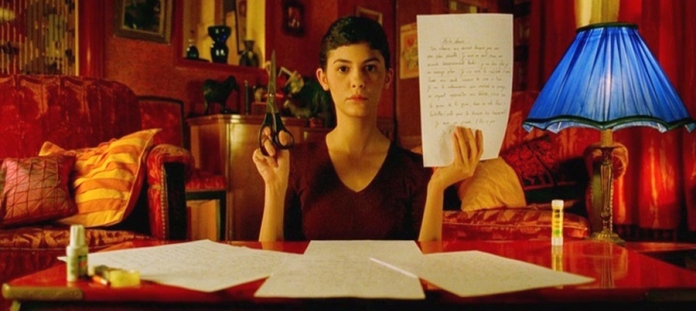

Schlesinger had set Christie on the path to stardom with her small role in his second film, Billy Liar (1963), and Darling capped off a near-meteoric rise in the same year as her enormous hit Doctor Zhivago, a hell of a one-two punch by any standards. Christie herself preferred her measured, subtle performance in Zhivago, but it’s easily discernible why she won for the more modest film, where she’s front and centre throughout. Darling’s protagonist, Diana Scott, is supposedly narrating her life story for Ideal Woman magazine, for which ads are plastered over other posters trying to raise awareness of third-world poverty. Her life proves to be one of those dizzying arcs that reflects the switchback ride of Swinging London at the time, full of starlets who shot to fame and then descended to a variety of fates. As a young, married woman with pretences to being hip and hoping to have success as a model, she was picked off the street to be interviewed as an example of modern youth by slightly world-weary TV producer and host Robert Gold (Dirk Bogarde). A dissatisfied intellectual who responded to Diana’s overboiling vivacity with his own, suppressed, playful energy, they soon became lovers. Diana left her young husband, and Robert his wife and children, to shack up in an initially happy no-strings-attached cohabitation; Robert was open to letting Diana pursue whatever extracurricular fancies she had as long as they weren’t anything serious.

Diana’s decision to abort Robert’s child sent her into a momentary emotional spiral, but she returned to him. When she began deceiving him over her trysts with coldly charming plutocrat playboy Miles Brand (Laurence Harvey), however, a furious Robert walked out on her. She took comfort in a close friendship with a gay photographer, Mal (Roland Curram), who, along with Miles, helped her gain a break as the face of an ad campaign for chocolate, and they travelled through Europe together. Diana received a marriage proposal from Prince Cesare della Romita (José Luis de Villalonga), a middle-aged Italian royal with a castle full of kids whose eye and mind she caught when she came to his estate to shoot a commercial. Upon realising her relationship with Miles will never develop beyond hedonistic indulgence, and despairing of ever patching things up with Robert, she finally married Cesare, only to find herself even more thoroughly trapped by the ornate sterility of the prince’s home and his mostly absentee status.

Darling plays in some ways as a feminine companion piece to the following year’s Alfie and other Free Cinema works of the period like This Sporting Life (1963). Whilst reflecting on contemporary problems, their narratives evoke the structures of Regency-era English novels with their picaresque narratives and case study-like interest in characters as social exemplars (small wonder Schlesinger’s New Wave teammate Tony Richardson adapted Tom Jones), and follow a hero in his or her wayward efforts to construct a truly self-actualised life, but often, unwittingly passing a point where an irretrievable mistake has been made. Like Alfie, under the modish chic, it carries a whiff of reactionary distaste for the new, but it’s truly about the crisis of not being able to live within a traditional mode of life without being able to find anything satisfying to take its place. Darling is particularly noteworthy in offering a female avatar for this recurring drama, one who seems to have it all: young, beautiful, and willful enough to get what she wants, but unsure how to keep it, Diana takes advantage of the changes in the world that can allow a provincial petite bourgeoise like her to become an “It” girl, and yet the machinations that promote her, rather than representing an age of emancipation, reflect a deeply meretricious world. “I’m very handy on a telephone, too,” Miles warns her after she boots him out of her apartment with an insult, reminding her that his kingcraft that helped her get ahead can bury her, too.

But Diana is uncertain just exactly what she wants. Fascinated and turned on by Robert’s intelligence and worldliness, she gravitates toward the scale of money and power that Miles can wield, and the once seemingly forbidden things he can show her, from the sexy allure of ultramodern corporate boardrooms to the incestuous world of the British upper class and the seamy ebullience of Parisian bohemia. The temptation to give one’s self over to being entertained by the rich, and thus owned, is one Diana gives into when she sneaks out of an audition to spend the day with Miles. This theme echoes on a larger level in which Schlesinger and screenwriter Frederic Raphael (whose later screenplays for films like Two for the Road, 1967, and Eyes Wide Shut, 1999, often returned to the theme of people in love who hurt each other in complex ways, depicted against a panoramic, satiric scope of interest) posit the degree to which the shock of the new and the age of liberation is actually a shallow marketing invention, one for which Diana is an ennobled consumer. Her own most genuine act of rebellion is to shoplift from a supermarket with Mal as her gleeful helpmate. Her and Mal’s relationship, which takes up a chunk of the film’s middle third, is defined by its thankful lack of sex and ease of companionship for Diana after the emotional bruises of her time with Robert and the greasy chill of her erotic fascination with Miles. But even this alliance runs into a roadblock when Mal sneaks away for a sexual escapade with a handsome waiter, and she’s both teed off and interested enough to be the next one in the waiter’s bed.

Schlesinger was really pushing the boundaries of what mainstream cinema could handle at the time, and undoubtedly his own homosexuality drove him to portray Mal in the warmest and most easygoing of fashions. Otherwise, his eye is an unforgiving one: a painstaking portraitist with his main characters, Schlesinger renders the background as a Hogarthian sprawl of acid-dripping mockery and caricatures. Robert introduces Diana to a respected old author whom he presents as the moral centre of the film—Matthew Southgate (Hugo Dyson), who became world-famous in spite of entirely shunning the limelight: he explicitly contrasts the rest of venal pack. Schlesinger offers splendid satiric vignettes, from a glimpse of the tacky B-movie Jacqueline, in which Diana plays the title character, murdered in the first scene, cueing a spot-on send-up of the Hammer type of psycho-thriller, to the travails of making TV ads. And there’s the society gathering Miles takes Diana to that is full of British magnates and politicians, resplendent in their racism, patronisation, and on-the-quiet libidinous indulgence, and the grossly try-hard hipster party he takes her to in Paris, replete with sex acts as entertainment and nasty games where participants are called upon to artfully insult other guests—a challenge Diana rises to with bravura in taking down Miles a peg or two. Thanks to her looks, Diana can gain access to the great world, but her actual part in it is passive: she is a commodity, and Cesare buys her, in essence, with his good manners.

The arc of Schlesinger’s career had moved from the kitchen sink Midlands drama of A Kind of Loving to the fantasist drawn to and shrinking from the bright lights of London in Billy Liar, to this portrait of a girl shocked and delighted by the world at large. Indeed, Darling is as an artwork a little like Diana herself: beautiful, open, playful, gobsmacked by perversity in a faintly provincial fashion, and finally, a little frustrating. Darling and Schlesinger’s subsequent Midnight Cowboy (1969) were easily embraced by the mainstream and showered with Oscars in spite of their provocative subject matter and stylistic vigour because they are, at least in one manner of speaking, quite conservative: they make merciless fun of the arty counterculture and depict protagonists finally skewered by their efforts to find a way out of traditional roles. But that summary is a little reductive. Schlesinger’s efforts to be unstintingly honest were often brutal, but necessarily so. Like Thomas Hardy, whose Far From the Madding Crowd was to be, almost inevitably, Schlesinger’s next and probably greatest film, he looked at the lives of his characters as inseparable from social context and personal character fibre, in spite of all impulses to rebel and transgress; this is distinct from traditional morality plays, although there’s an aspect of those at work here. Schlesinger perceives a world full of people who, when it gets right down to it, use each other without compunction, and true affection is a brittle thing that can be as potentially torturous as any hate.

Scenes in which Diana takes refuge for a short time with her conventional sister and her husband, and contends with awkward set-up dinner dates with their idea of good potential mates, makes immediately apparent why Diana’s willing to risk it all for something out of the ordinary. She marches through an unadventurous landscape with teasing shows of wit and self-possession, keeping pace with Robert’s syllogistic blarney, and, after proposing to Miles how interesting it would be if it took three sexes to have a child (“Don’t you think we have enough trouble with two?” he ripostes), and explores many different types of sexual pairing, short of lesbianism—and even there she has a close graze with an interested sculptress (Annette Carell) in Paris. Yet she inflicts punishment on herself for committing acts for the sake of her worldly dissatisfaction, like her abortion and her falling out with Tony. She finally seeks a retreat into borrowed tropes of a supposedly settled and ordered culture, including returning to her Catholic faith and in marrying the prince, but this, too, turns out to be fancy wrapping on a convenient sham. That she finally ends up pining for the intimate joys of her relationship with Robert, whose relative lack of money and flash initially disappointed her, is a sentimental reflex on her part that he won’t indulge. This builds to a desolate conclusion in which, after a night together in reunion, he ignores her pleas that she wants to come back to him and makes her return to the prince. For all of their pained longing for each other, Robert’s insistence on honesty, which demands they both have to start their lives again from scratch if they’re to have any real lives at all, is sour but honourable.

The way Schlesinger keeps his landscape vibrating refuses moral lessons that are too easy, thankfully, and aspects of his subsequent, best films are anticipated throughout. Bogarde and Harvey were cast in roles that deliberately played on their reputations already well-established in films before this, and both are customarily excellent: Bogarde’s skill as an actor is still relatively underrecognised. But it’s Christie who dominates with her supple and alert acting throughout, capturing Diana’s multifaceted liveliness and humour, her smarts and wiles, and also her slippery, elusive quality that signals a lack of a true inner compass, neither amoral nor truly self-aware. I particularly loved Diana’s explosion in a tube station when, after Robert calls her a whore, she begins ranting with a My Fair Lady Cockney accent and complaining he hasn’t paid her enough. The film’s dramatic highpoint isn’t her final bust-up with Robert, but a scene that evokes Kane’s devastation of Susan’s room in Citizen Kane (1941): consumed by anxiety and despair, Diana stalks through the prince’s ornate house, strips off her clothes, and assaults not the suffocating finery, but the Christmas cards over the fireplace—paltry signifiers of emotional ties. Even if Darling does show its age in some respects, the cast’s perfection is eternal, and the filmmaking is still giddily entertaining.