.

Director: Matt Reeves

Screenwriters: Peter Craig, Matt Reeves

By Roderick Heath

Here there be spoilers…

With Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan’s versions of Batman now sliding into generational memory, and Zack Snyder’s firmly written off as a blind alley, the time is apparently ripe for another reimagining of a character now firmly lodged as a supreme archetype in pop culture. Somewhere along the line Batman replaced Superman as the preeminent comic book hero, supplanting the dream of vast power and matching, rigorously honed moral perspective – the fantasy embodiment of mid-20th century America – with something more concrete and troubled. When Batman first emerged as a comic book character as created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger in the late 1930s, he had obvious roots reaching back to the Scarlet Pimpernel and his prodigious pulp fiction and funny pages offspring, including Zorro, Doc Savage, The Green Hornet, The Lone Ranger, and The Shadow. Batman was also rooted in the cultural climes of the 1930s, a time when gangsters were celebrities, and movie theatres were filled with the influence of the German Expressionist cinema movement with their reality-distorting gravity of style as exemplified by movies like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and Metropolis (1926), all of which inflected the comic’s vision in ways overt and clandestine. Today Batman has survived where only vague cultural echoes of the property’s inspirations resound.

Ever since Taxi Driver (1976) firmly inscribed itself as an ideal model for summarising a dank facet of the modern American psyche where everyone’s waiting for the real rain to come and wash out the streets, Batman, revised radically from the playful version of the character popularised by the 1966-68 TV series starring Adam West, suddenly found himself the perfect mediating vessel. Batman is defined by his seemingly incoherent yet perfect assemblage of traits. Rich but forlorn. Free but obsessed. Orphaned but surrounded by a form of family. Living as an emblem of all that’s desirable in worldly terms yet lacking desire. Batman appeals to the whole swathe of a modern movie audience. To the young, in his ingenious gadgets and naggingly memorable mystique, and his simultaneous defiant attitude towards and exemplification of parental authority. To teenagers in his self-emblazoned embodiment of torment and sceptical campaign to right institutional wrongs. And to adults as the most quasi-complex of superheroes, the one whose splintered psyche is animated in the apparel of his universe. The sprawling old-world manor as the emblem of civilisation with the bole of secrets lodged underneath. The villains who all reflect Bruce Wayne’s alienation and splintered identity back at him. The diffused yet pervasive and ambiguous sexuality.

With The Batman, director Matt Reeves attempts a task of synthesis, charting a middle course between the dusky fantasia of Burton’s films and the sly pseudo-realism of Nolan’s, whilst also harking back to aspects of the material’s early days. His stylistic inspirations, are chiefly movies like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and David Fincher’s Se7en (1996), both themselves children of Taxi Driver, and also nod to a brand of burnished style popular in the 1980s as practiced by the likes of Walter Hill, Ridley and Tony Scott and others, directors who created stylised worlds where the streets were always wet from rain and reflected multi-coloured neon whilst some raffishly beautiful people got in trouble. Given how boring so much contemporary filmmaking looks, it’s not surprising that kind of movie is becoming more and more of a touchstone for more ambitious emergent directors. Reeves takes his stylistic conceits and thematic inferences to obvious extremes – it rains so much in his Gotham City I wondered if it’s supposed to be located in the tropics. Reeves, who once upon a time cowrote Steven Seagal and James Gray movies, debuted as a director in spectacular style with the facetious but compelling found footage monster movie Cloverfield (2008) and followed it up Let Me In (2011), a solid remake of the Swedish vampire movie Let The Right One In (2008) and a couple of entries in the renewed Planet of the Apes series. Despite his writing background Reeves belongs to a cadre of current directors also including Joseph Kosinski and Gareth Edwards who try to fuse highly technical filmmaking with visual artistry.

The Batman also splits the difference in taking on the material in at once exacerbating still further the more serious, grounded aspect of Nolan’s films whilst providing an ironically revitalising stab at providing a classical kind of Batman story. Whilst the very familiar tragedy of the deaths of Bruce Wayne’s parents is invoked in the story, it’s not portrayed yet again, nor any other element of his origin myth. Moreover, The Batman sets out to emphasise the title character’s prowess as an investigator, harking back to his status as the “world’s greatest detective” in the comics but long quelled in adaptations. This film’s version of Bruce (Robert Pattinson) has been inhabiting his Batman guise for two years. He’s become, thanks to his alliance with Gotham Police Lieutenant Jim Gordon (Jeffrey Wright), a folkloric figure skirting the outermost fringes of legitimacy, regarded with hostility but not quite outright violence by cops, just infamous enough to scare street punks when his searchlight signal emblem is projected in the sky but not yet sufficient to scare the criminal outfits about town. Despite the newly thick pall of goth-noir self-seriousness, in certain ways The Batman resembles the 1966 film of the West imprimatur, directed by Leslie Martinson, more than any other movies of the franchise since, insofar as much of it deals with the essential story pattern of Batman trying to follow a breadcrumb of trails left for him by The Riddler which eventually proves to point to a project of anarchic and iconoclastic intent.

The film’s choice of title confirms a yearning to restore some mystique and mystery to the character, appending a definite article to make him seem less personable and more like the creature haunting the dreams and sneering quips of his criminal prey, and nodding back to the more arcane writing style of the early comic books: he is as much a rarefied emanation of Gotham City’s psyche as The Joker and The Riddler. And so the film opens with Bruce musing in his diary on the purpose of the Bat Signal as a tool of intimidating criminals, warning them he’s out and about, whilst also quaintly musing that he doesn’t merely hide in the shadows, but “I am the shadows.” That line seems like something a teenage boy overly fond of Poe and Nine Inch Nails might write on a schoolbook. But Reeves cleverly insinuates the Batman guise is in part a riposte to the kinds of club-like disguises becoming popular amongst Gotham’s thug element, like a gang of clown make-up-wearing goons who like filming their random acts of brutality and set their sights on a lone commuter (Akie Kotabe) who tries to slip away unnoticed. The gang corner him on an L station only for Batman to emerge from the darkness and beat the living hell out of the gang, saving special rough treatment for one who vainly tries to shoot their masked and armour-plated vigilante. Batman isn’t calling himself Batman yet, instead repeatedly referring to himself as Vengeance, personified.

Gotham is currently in the throes of a mayoral election, with the plutocratic incumbent Don Mitchell Jnr (Rupert Penry-Jones) duking it with young, upstart, reformist challenger Bella Reál (Jayme Lawson). But Mitchell is attacked in his office and beaten to death by a lurking figure who wears a crude, bits-and-bobs disguise. Gordon contrives to bring Bruce in to view the crime scene, because a letter addressed “To The Batman” was found taped to Mitchell’s body, which was also missing a thumb. Gordon’s former partner, now the Commissioner, Pete Savage (Alex Ferns), objects strongly to Gordon’s action, but Bruce is able to sort out the killer’s queasy blend of sick humour and intricate puzzles leading to clues, with the help of his butler, pseudo-father, and former intelligence officer Alfred (Andy Serkis). When Bruce locates Mitchell’s thumb, tethered to a fingerprint-unlocked thumb drive, he and Gordon open it, to find it contains photos of Mitchell with a bruised young woman outside The Iceberg, a popular nightclub, controlled by crime lord Carmine Falcone (John Turturro) and his lieutenant Oz, known by his underworld sobriquet The Penguin (Colin Farrell). The thumb drive also, the moment it’s accessed, automatically sends the pictures out online. The mysterious killer, who calls himself The Riddler, soon makes a victim of Savage by kidnapping him and torturing him to death, and makes clear he’s pursuing some vendetta against those he brands the corrupt and hateful overlords of Gotham’s institutions, both official and criminal.

Bruce visits The Iceberg in Batman guise and, after bashing his way inside, talks with The Penguin, but his eye is caught by club employee Selina (Zoe Kravitz), whose distinctive boots are glimpsed in the photos of Mitchell. Tracking her, Bruce finds she’s harbouring the bruised girl, Annika (Hana Hrzic) in her apartment, and soon observes her in action in her metier as a cat burglar, breaking in to Mitchell’s apartment to try and steal back Annika’s passport. Bat and Cat form an uneasy alliance as Selina agrees to become Batman’s eyes and ears and penetrate the exclusive club-within-the-club inside The Iceberg called 44 Below, which regularly entertains Gotham’s supposed elite of law and order. There she encounters the city’s chatty DA, Gil Colson (Peter Sarsgaard), and picks up slivers of information that begin pointing along the path to uncovering a conspiracy linking Falcone and the city bosses. Meanwhile Colson himself is snatched by The Riddler and employed in a most spectacular fashion to crash Mitchell’s funeral.

The Batman betrays efforts to keep up with the zeitgeist: where in Nolan’s films Batman was necessary because the police were under-resourced and outmatched in a cynically neoliberal epoch, here it’s because they’re largely an inherently corrupt organism serving fraudulent oligarchy. The Batman reiterates ideas employed in Nolan’s films, covering similar ground to Batman Begins (2005) in portraying efforts to take down Falcone, a representative of familiar organised crime, only to create a vacuum where more perverse villains will burgeon. Reeves also revisits and intensifies The Dark Knight Rises’ (2012) themes of collective punishment by self-appointed anarchist-avengers, and choice of characterising Catwoman not as a sly opportunist or, like Burton’s take, a crazed and eroticised avatar of feminist rebellion, but a blunter, demimonde-produced rebel locked in a dance of duality with Batman in seeking retribution. That said, The Batman hews in its darker, weirder bent to elements of Burton’s vision, presenting a more detailed and realistic version of its perma-noir city replete with Edward Hopper-esque diners and looming urban-industrial fixtures. Fincher’s Se7en and Zodiac (2007) are also evident reference points in remaking The Riddler over as a tricky, ironic, viciously moralistic foe reminiscent of Se7en’s John Doe, and sporting personal branding in his logo and cryptic puzzles reminiscent of the Zodiac Killer’s. The Riddler is a menacing, deeply malignant weirdo who contrives to have one character’s face eaten off by rats. Taking inspiration from something like Se7en, an exemplification of a movie that contrives to look grown-up but actually disseminates the worldview of a morbid high schooler, doesn’t charm me.

Allowing that kind of Sadean edge also pushes The Batman into territory verboten to kids and a mite unpleasant for grown-ups too. Reeves is at least judicious, implying and skirting such grisly things whilst avoiding overt gore. The Batman labours to construct a mood of creeping, incipient dread infecting all things that makes Burton’s once-controversial style choices – remembering that he was the one who fatefully inducted darkness and grit into the lexicon of the modern fantastical blockbuster – seem nearly as playful and frivolous as the West series by comparison. The pall is emphasised by Michael Giacchino’s grand and menacing score, which builds themes, in radically different counterpoints, derived from “Ave Maria,” which The Riddler adores. The film’s extreme length, at nearly three hours, is enforced in large part by Reeves’ extremely deliberate pacing, and it’s both a plus and a minus in terms of the movie’s overall success. Reeves strains to give every gesture and plot turn a sense of weight and foreboding, each revelation leading on to another, grimmer truth. One real plus of The Batman is that it believes in basic principles of popular cinema as a blend of story and style. Even if the story is very familiar as it largely from god knows how many urban thrillers and conspiracy dramas, it’s more than just a convenience to pass the time between action scenes and cheap jokes that come every five minutes to sate seat-kicking 13-year-olds.

Despite its veneer of social invective, The Batman is as nostalgic in its way as anything in current cinema, looking back longingly for an age of romantic desolation in big cities rather than the smothering blandness of a gentrified age. Preoccupation with the dark side of the Batman fantasy as rooted in vigilantism, a contemporary concern augured deep in the zeitgeist by films like Dirty Harry (1971), Death Wish (1974), and Taxi Driver itself as well as perpetual tabloid controversy, was initially interrogated in the likes of Frank Miller’s graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke before then being transmitted into the movies, supplanting the old, simple image of the masked, heroic crime fighter. Dirty Harry itself can be seen as both a derivation and anticipation of eras in Batman lore with Harry as the Dark Knight and Scorpio as The Joker. The septic avenger angst is now so familiar, in short, as to be as big a cliché as anything it was meant to dispel, especially when it has become, in its own way, just as romanticised. Reeves however tries to take it seriously in his own way. The film makes much of the common roots of Bruce, Selina, and the Riddler’s motives to become extra-judicial punishers, with sharply divergent sociological and psychological paths trodden to become what they’ve become. This kind of characterisation tries to take on themes of inequality and privilege, with Selina explicitly suggesting only someone born rich can afford morals. Trouble is, this treads very close to making very conservative arguments: Bruce, rich and comfortable despite his traumas, has the luxury of being good; Selina, hardscrabble survivor, is more focused, angry, and ready to countenance theft and murder; Riddler, product of an orphanage, is a maniacal slayer, forging a shadow army out of the dispossessed and the never-had like the embodiment of every upper and middle class nightmare. Good things those lower orders are being kept in hand.

Of course, there are other ways of reading this. Reeves’ attempt to return the material to a zone that feels more psychologically animate makes it easier to see the characters as facets of the same personality – Bruce/Batman as superego, Selina the ego (and anima), Riddler the id. Bring on the Joker for superficial antithesis. Farrell’s Penguin is left out of this equation. Burgess Meredith’s fabulous performance in the West series made the Penguin the most intelligent and impudent of Batman’s opponents, so he took on a greater importance there than in other mediums. Here the character is most plainly used as a movie buff and acting fan reference point: Reeves has cast Farrell and covered him in make-up to do a pinpoint imitation of Robert De Niro’s similarly transformed performance as Al Capone in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987). Reeves and Farrell do sneak in a deft reference to the more traditional version of the character as he’s left waddling when Bruce and Gordon tie his feet after capturing him for interrogation. There is nonetheless appropriate cunning in positing the character in a milieu that’s an extrapolation of a 1930s movie gangland (Jared Leto’s much-mocked but interesting performance as the Joker in Suicide Squad, 2016, also tried to bridge such roots, but with his nods going to James Cagney and George Raft). There’s a coherently and realistically paranoid lilt to the film’s vision of the official ruling class and underworld bosses of a city locked in an uneasy, mutually contemptuous but inescapable gravity, a state of decay where Batman seems most justifiable.

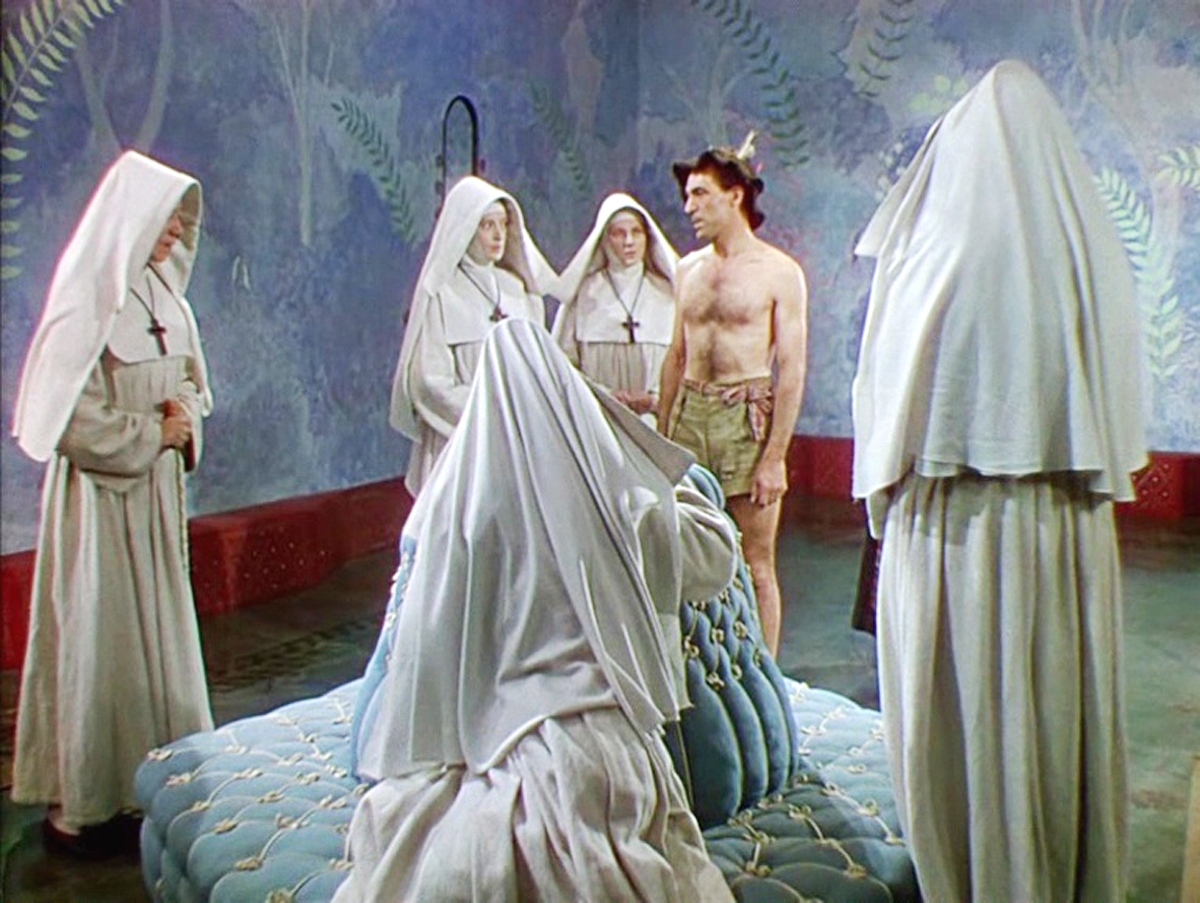

The neurotic dance of attraction and disdain between Bruce and Selina, constantly grazing each-other whilst wearing their sexuality as masks, has long been a sustaining element of the material, and Reeves to his credit doesn’t awkwardly skip around it like Nolan did for most of The Dark Knight Rises, although he also stops short of acknowledging it as deeply pathological as Burton indicated in Batman Returns (1992). That film, which, despite being violently uneven and about 70% misfire, sported in Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman a definitive characterisation as a post-Madonna, pre-#MeToo sexual avenger. Reeves aims at least to let the couple evince attraction that feels more bodied and hot-blooded than the constant puppy love found in the Marvel Studios series, complete with the odd bit of snogging, even if their relationship is still ultimately stymied and chaste. Bruce’s attraction to Selina is part of his character journey as she taunts his code but also ultimately reinforces it, more perhaps than The Riddler does, through her actions.Unlike a great majority of moviemakers today, Reeves seems aware that he has two movie stars on hand to do what people used to go to movies to see, and so he bravely allows the audience to enjoy watching two very hot people play characters whose chief affinity seems to lie in both being vinyl fetishists. Kravitz, having a good year between this and her starring role in Steven Soderbergh’s Kimi, has just the right screen presence and persona for the role, a gamine projecting a quality half-feral, half-wounded beyond repair, driving her to become a kind of urban guerrilla fighter fighting a private war. She looks so hard, so gimlet-gazed and self-contained, that the sight of her responding to Bruce reveals someone who might well rather be an animal remembering she’s human. That Selina clearly swings both ways is also signalled in her apparent relationship with the victimised Annika, who vanishes from her apartment, apparently snatched by Falcone and his people.

Later Annika’s corpse is discovered by Bruce and Selina when they spy on a drug deal orchestrated by The Penguin. The Penguin’s goons fire on them when they realise they’re being spied on, but Bruce brings out the Batmobile to chase down The Penguin in a spectacular, sometimes quasi-impressionistic highway chase. Reeves’ cinematic setting, with the sepulchral visual palette and Giacchino’s thrumming, tolling score, reach towards grandeur, and yet Reeves labours at the same time to reset Bruce/Batman at basics – his bulletproof suit and contact lens cameras are fancy stuff but most of the rest of his operation is quite low-tech, reliant on simply hitting stronger and faster than opponents through relentlessly honed skills. The Batmobile is essentially just a souped-up muscle car which, it’s hinted through his predilection for stripping his motorcycle down to components and back again, he likely built himself. Reeves, who keeps any tendency towards boyish delight on a tight leash for much of the movie, at least can’t disguise it in the sense of moment when Bruce first fires up the car, glimpsed in silhouette, revving up the motor with thunderous grunts and spurts of flame to give chase. The chase concludes with an equally iconographic vignette as The Penguin gazes on, battered and mortified, inside his upside-down car as the Caped Crusader emerges from his vehicle, every inch the gothic nightmare to the criminal element he intended, and approaches at a slow, menacing mosey.

In tone and outlook The Batman just about as far as it’s possible to get from the West film and series without perhaps becoming a snuff film, and yet it’s still recognisably the same stuff. Reeves’ work tries hard also to distinguish itself from Nolan’s trilogy. Where Nolan’s films had their arrhythmic, sometimes borderline incoherent visual jazz and propulsive editing, Reeves goes for a stately tension, with painterly smears of drenched colour and punctuated by eruptions of chaos. An early scene where Bruce fights his way into The Iceberg, creaming bouncers and wiseguys, is sleek and bleakly beautiful and touched with an edge of abstract artistry by the flashing lights and booming music, in comparison with a similar scene in The Dark Knight (2008) where Nolan’s gibberish cutting simply located Batman in the midst of a brawl. Later, Reeves reiterates the edge of abstraction to intensify rather than mute an action sequence, as Bruce fights his way into The Iceberg in trying to rescue Selina from her own maniacal choices, his stalking, silhouetted, nightmarish guise glimpsed in the flashing of machine guns as their bullets bounce off his armour. There’s a fierce beauty to such moments, and the film as a whole, and if I liked The Batman more than Nolan’s films, it’s because Reeves is a far more elegant filmmaker. On the other hand, Nolan’s expansive, fidgety narratives kept tripping over themselves because they tried to do too much and betrayed Nolan’s hyperactive synapses, whilst The Batman tries to make a busy but essentially straightforward narrative into the stuff of epics.

There’s a lot of to-and-fro in the plot involving Selina’s covert connection to Falcone – she’s the illegitimate result of his contemptuous fling with one of his club dancers – and the conspiracy The Riddler’s project is meant to both avenge and reveal. Whilst Reeves does manage to keep most of this in balance, The Batman would ultimately have been better, indeed close to the classic of its genre, if it had less focal points. Reeves introduces a motif in the film’s very first scene as The Riddler spies on Mitchell, who plays a bit with his son, dressed as a ninja and fighting invisible enemies in his father’s office. For a moment you think this might be a prelude depicting Bruce in his childhood. Instead the lad, orphaned by The Riddler’s actions in a bitter irony, becomes an emblem for Bruce, who keeps seeing him and experiencing moments of powerful identification that he must keep secret: any expression of emapthy would be a disastrous unmaksing. He saves the boy’s life during a later eruption of chaos, action being the only way he can express and contend with such sad knowledge. Bruce follows the breadcrumb trail to find that not only did Falcone manipulate the city’s honchos to get his former boss locked away but also brought them in as partners in the drug trade, and they divvied up the large urban renewal fund that Bruce’s father established for his own, brief mayoral run not long before he was killed. This in turn obliges Bruce to consider the possibility his father was also corrupt, when The Riddler suggests he had a journalist murdered for prying into his private life, and also to look out for himself and Alfred when The Riddler makes clear Bruce is his next target. This swerve of story essentially goes nowhere. Alfred, wounded in an assassination attempt on Bruce’s life with a letter bomb, angrily tells Bruce the proper story, which does leave Thomas Wayne a compromised and culpable but not villainous figure. The main point of this seems to be to release Bruce from feeling entirely crushed by the mythos of a heroic father (and also that mental instability might be as much his inheritance as Wayne Enterprises) and also able to finally embrace Alfred as decent substitute, as the pair have interacted uneasily through the movie on this topic. Serkis, unusually but effectively cast, characterises his Alfred as an aging man of action eased into a quietly circumspect life of nurturing whilst still musing on his days “in the Circus” (vale LeCarré) and operating as the paternal figure Bruce needs whether he wants it or not. He’s really good and the film needed more of him.

The same thing can be said for Pattinson. For anyone who hadn’t seen any of his performances since his star-making but largely derided turns in the Twilight series, his casting was liable to be bewildering, just as it was inevitable-feeling to anyone who had watched him in the likes of Cosmopolis (2012) and High Life (2019). Pattinson, whose features are the stuff of the officially handsome yet from certain angles appear quite Boris Karloff-esque, knows well how to channel his image towards playing neurasthenic adonii, and twists it a few more turns here. Pattinson’s avowed inspiration for his characterisation was Kurt Cobain as the poster boy for troubled greatness, but with his stringy, floppy haircut looks more like Crispin Glover, whilst his Batman costume with its high, very pointy ears is vaguely reminiscent of the first onscreen appearance of the character, in Lambert Hillyer’s 1943 serial. Refusing to get jacked in a Chris Hemsworth fashion, Pattinson nonetheless projects a newly intimidating physical presence, and he depicts Bruce’s physical bravura well, particularly in the opening fight scene where he mercilessly bashes a hapless thug into submission as much to show his pals what they’re up against as to lay him out. Here the film’s thesis, of Batman as an empowerment fantasy concocted by a haunted young man which he then relentlessly adapted himself into, is illustrated without any further underlining required.

Pattinson’s Bruce and Batman aren’t yet clearly divided personas: in Batman guise he doesn’t put on any kind of gruff-rough voice (thankfully), whilst Bruce Wayne is living as a detached and obsessive recluse neglecting not just a social life but also the family’s waning fortunes, far from the studied appearance of a playboy as stolen from Percy Blakeney. Bruce’s habit of venturing into deadly situations without a gun is both defining and also galling, as Gordon quips, “That’s your thing,” as he pulls out his pistol for a venture into an old dark house: not everyone has a few million dollars’ worth of carbon fibre on hand. There’s also an interesting disparity in Bruce’s personal fame and that of the Batman, who is still a spreading legend, whereas Bruce is instantly recognised despite his reclusiveness as the avatar of Gotham’s elite, both glimpsed during his attempts in both guises to get into The Iceberg. Bruce’s decision to appear at Mitchell’s funeral results in many turned heads, including that of Falcone, who scarcely ever leaves his headquarters above The Iceberg Lounge: a mayor’s funeral is the last social unifier. Which is then crashed as a car smashes through the cathedral doors and scatters the crowd before slamming to a halt against the altar. Colson emerges from the vehicle with a bomb tied about his neck and a cell phone taped to his hand. Bruce returns in Batman guise and converses with The Riddler over the phone, who cruelly forces Colson to expose his own corruption before blowing him to pieces.

Bruce, knocked out cold by the blast but protected by the suit, is then carried to the police headquarters where arguing cops want to unmask and arrest him, but Gordon convinces them to let him deal with the captive, and gets Bruce to make a break for it. Here the narrative takes a risk with logic in making you wonder why the cops didn’t unmask him right away. The apparent explanation is Gordon’s shepherding prevented this, but it’s still a bit thin. Better, perhaps, is the notion the rank-and-file cops already largely feel Batman is their last, best friend, in a story that tries to dramatise the longest bow of the basic Batman format, the embrace by the police of a civilian dressed as a bat as a trustworthy, even vital ally: Reeves gives it his best. As far as finally letting Batman the Detective have his day, The Batman is absorbing, even if some of the expository dialogue Pattinson is stuck mouthing is exasperatingly obvious. The trouble is Batman doesn’t come out of it looking that great as a detective, with The Riddler holding his metaphorical hand and leading him step by step into his malignant plan. Bruce eventually foils Selina’s avowed design to assassinate her father in punishment for his many sins, but just as Bruce drags Falcone out of his headquarters with the aid of true cops, he’s gunned down by a sniper from an apartment across the street. This proves to be The Riddler’s home: when they invade the apartment the investigators find evidence of his activities but not their quarry, but he’s soon located drinking coffee in a nearby diner.

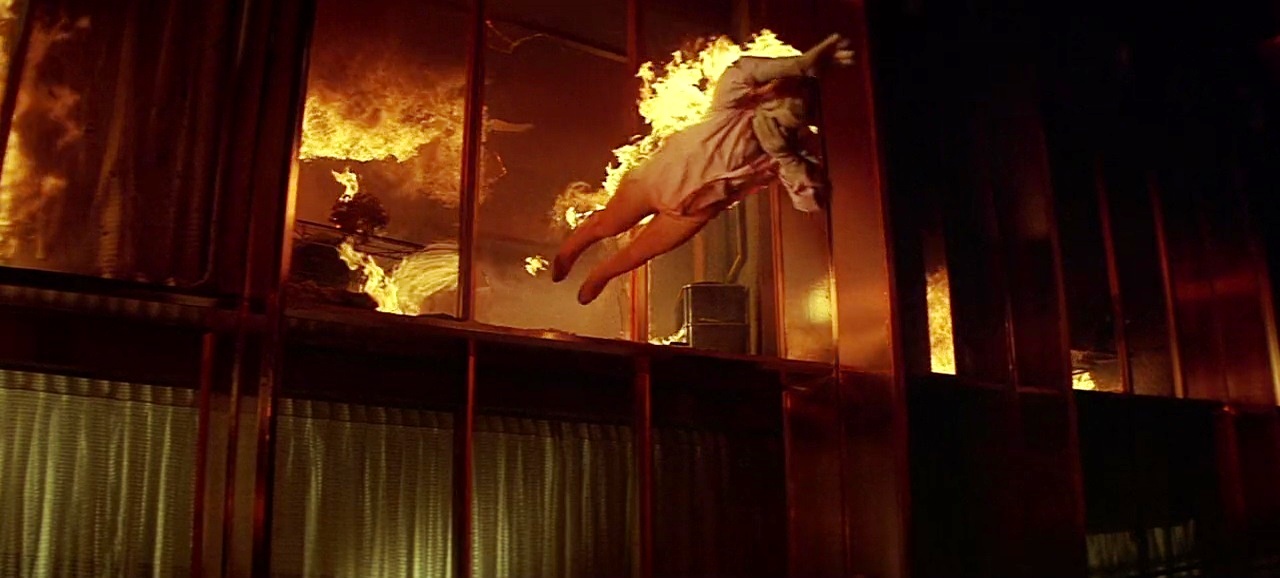

Dano, who can play weirdos in his sleep by now, nonetheless modulates his performance mischievously, the figure of bleak, volatile menace captured on cell phone video screen supplanted by a twee, damaged pervert who sometimes whispers in alternation with piercing, drawn-out, quasi-autistic moans that abruptly become words. Here however the film hits a speed bump of narrative intent. With The Riddler imprisoned, Falcone dead, and The Penguin neutralised for the moment, the movie lacks a villain. Turns out The Riddler has a network of fellow internet oddballs and angry orphans who adopt his guise and follow his plan to wreak havoc at Réal’s inauguration whilst bombs he planted around the city unleash flooding torrents. Here Reeves labours to evoke both obvious historical parallels, with shots modelled on the flooding of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and movie models, nodding to The Manchurian Candidate (1962) with the assassins lurking in the rafters of the “Gotham Square Garden” to kill Réal. This larger plot, in a campaign of havoc previously confined to one creep, takes everyone by surprise, including the attentive viewer. There’s definitely something interesting in The Riddler replicating himself like glitch code in the city matrix by assimilating other damaged loners and rejects, but where the film might have devoted some of its copious running time to setting this up, it instead sprung as a shocking twist.

The spectacle of the flooding city could have been a memorably apocalyptic signature, but it’s rather flatly done, and Batman can’t do much about it. At least Bruce and Selina can intervene to beat up The Riddler’s assassins in a potent action scene, even if there’s still the problem of their foes not really having any identity: they’re just anonymous thugs. Bruce is almost knocked out of the battle when one of the goons shoots him up close with a shotgun, requiring Selina to help him, and then giving himself an adrenalin injection to roar back into battle as a berserker. This gives way to a visually striking and affecting coda as Bruce, descending into the floodwaters to rescue some cowering Gothamites, holding a flare aloft as a beacon amidst carnage and realising he needs to be more than Vengeance, and he embraces the role of a public hero rather than someone merely following his own obsession. I liked this final flourish, one that endows Bruce/Batman with a character arc without reiterating things that have been done to death with the character. The film ends in curiously languorous fashion with Bruce and Selina going their separate ways, lingering on shots of them riding motorcycles alongside each-other – a definite motif in the film – but then diverging.

The Batman is a peculiar creation at once endemic of and off the beat of contemporary Hollywood, in that it doesn’t entirely succeed, but also feels like a real movie. It takes chances and pulls most of them off, and whilst derivative in vital aspects it has an aura that’s specific, dramatic and aesthetic musculature that’s substantial. The Batman recalls expressions of Hollywood imperial stature like Ben-Hur (1959) or Cleopatra (1963) or Doctor Zhivago (1965), but instead of depicting some great confluence of history and myth it confidently expects an audience to sit through a three-hour mood piece purely because it’s a Batman movie. It comes close to describing an ideal of what a Batman movie can be, even as it can’t quite embrace the extremes it should be heading to, and cuts itself off ultimately from the awareness of the kinky wish-fulfilment Burton, for all his faults, understood. I wish the script was less pedantic and had some of the more blasted romanticism and cynical poetry of its noir and cyberpunk models that Reeves successfully channels into the look of the thing. That it could have been about twenty minutes shorter without any real damage seems obvious. Indeed, the entire style of The Batman risks leaving behind the specific pleasures of pulp fiction and exchanging them for the last word in pseudo-seriousness. But that in itself makes The Batman arresting. If Reeves’ film is better than this might make it sound, and indeed close to my favourite outing to date for the character, it’s through the accumulation of elements, the tangible, powerful style and strong performances, that make it a big, woozy, uneven, but riveting experience. The film signs off inevitably with signals of sequels, apt in this case as The Riddler finds himself, despite his misery at his plan’s failure, making connection with a sardonic fellow prisoner (Barry Keoghan) in the next cell of Arkham Asylum, whose identity will be plain enough to protoplasmic fish in the Challenger Deep. And the very last shots of Bruce watching Selina vanish along a hazy, light-smeared Gotham street at dawn in his rear-view mirror, the duo having fought their way through into light at least, before Bruce sets his jaw and rides on to his mission, does capture that ephemeral pulp poetry the film seeks earnestly.